By Rob Feld

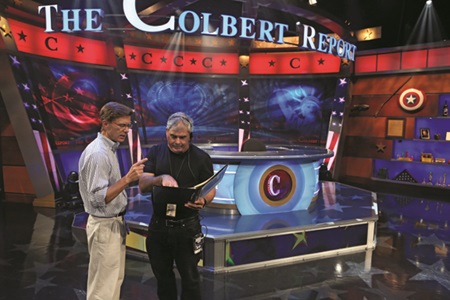

Hoskinson (left) goes over notes with stage manager Mark McKenna about what to expect in that day’s show.

Hoskinson (left) goes over notes with stage manager Mark McKenna about what to expect in that day’s show.

No matter which Kardashian is currently doing what with whom, in a political season the nation’s focus inevitably turns to the election and the myriad of characters that emerge from it. While the presidential campaigns may provide an embarrassment of riches for satire, poking fun at American politics is director Jim Hoskinson’s job every day on The Colbert Report.

Now seven years into its run, the show presents Stephen Colbert as a clownish right-wing pundit, commenting on the week’s events from behind a desk, talking to studio guests, or doing location interviews with members of the House of Representatives in mock serious segments such as “Better Know a District.” The Colbert Report mines humor from the idiocy of Colbert’s character, as he riffs on news videos and a cavalcade of pop-up graphics appear in the classic news anchor box over his right shoulder. It’s a half news, half morning show format that’s a perfect fit for Hoskinson.

The Connecticut native started as a cable puller on an early morning Disney Channel show where he sampled a variety of jobs and wound up in the control room as a Chyron graphics operator. He then became an associate director at CBS’ Inside Edition when Bill O’Reilly was anchor. This developed into a six-year directing job before he moved on to direct at Fox News. When the newly created Colbert Report went looking for a director, Hoskinson’s name was raised by co-executive producer Meredith Bennett, who had worked with him at Inside Edition.

“Fox News was certainly a visual model [for the show],” says Hoskinson of The Colbert Report’s early conception, “and Bill O’Reilly was one of the ideas for Stephen’s character, so it all sort of fell together.”

Hoskinson, with associate director Yvonne DeMare, uses a flexible camera setup to react to Colbert capers.

Hoskinson, with associate director Yvonne DeMare, uses a flexible camera setup to react to Colbert capers.

The style and grammar of the show has not changed much. In fact, Hoskinson’s first Emmy nomination (he has seven and a DGA Award nomination) was for only the tenth show they did. “Stephen’s character was born full-grown,” says Hoskinson. “Everybody understood from the beginning what his character was going to sound like, what he would say, what he would look like. I still find that first Emmy nomination kind of amazing. Stephen’s voice was so clear to him, the writers, and to me, which is the central factor in the early success of the show—we were all on the same page.”

From a directorial perspective, Hoskinson still had some things to learn. After all, this was a comedy show, not a news broadcast, which called for a different way of interacting with on-camera talent.

“In terms of The Colbert Report, doing news and doing entertainment are very different,” explains Hoskinson. “Stephen was much more comfortable in front of the camera than I had been used to. News people have a seriousness of purpose, and as a rule aren’t as comfortable in front of the camera because they’re not playing to it. They’re about delivering the news. Stephen was able to engage the camera in a way that I thought was pretty remarkable, and still do. That makes it a lot easier for me. We just have to follow what he does accurately, and good things happen.”

At the beginning of the election year, the show established the style and content of where it was going, and Hoskinson followed. Colbert set up a political action committee, “Americans for a Better Tomorrow, Tomorrow,” an actual super PAC he could use to parody the current state of American campaign financing. “One of the major stories of this fall’s campaign will be the influence of super PACs, and Stephen’s super PAC lets his character intersect with the real world,” says Hoskinson. “Stephen very quickly decided he didn’t have to be deskbound. In a news broadcast, the weather guy might be in the weather center, but we constantly take Stephen out from behind the desk in ways both real or imaginary. There’s a dimensionality. If a news set is two-dimensional, our studio space has always been three-dimensional; anything can happen in there. We’ve been able to embrace that, which has been very successful for us.”

Hoskinson uses a flexible camera setup in order to cover Colbert’s capers and, at times, capture the punch line with a cut to a different angle for a reveal or an anchor aside. His studio is equipped with three pedestal cameras, a jib, and a fifth camera that can go handheld if necessary. He can call a quick cut to a different angle for Colbert’s asides to the audience, block for Colbert’s shenanigans throughout their building on West 54th Street, and cover the numerous people who emerge from under Colbert’s desk.

“We’ve had Moses lead the Jews out of Egypt from under that desk,” Hoskinson recalls with a chuckle. “And apparently there’s a Starbucks under there, too. But again, it’s important to be able to react because, as opposed to news people who read the story right down the pipe, Stephen always has the option to do something different. We’ll sometimes do a whip around where he’ll turn through all four cameras in the space of a few seconds. That’s challenging. He’s very good at finding the camera but there’s a margin for error because he’s not easy to throw; if there is a little bobble or glitch, he can plow right ahead and that’s helpful to know.”

The style of Colbert’s interaction between Hoskinson’s active camera and the over-the-shoulder graphics was established right from the start. Hoskinson can call up to 100 graphics cues a night to bolster, undercut and counterpoint the absurdity of Colbert’s presentation. The various graphics flying on and off the screen, created by the show’s four-person graphics team, are like characters in and of themselves. In fact, the “over-the-shoulders” often provide the punch line, so if the timing of Hoskinson’s cues are off by a beat it would be like watching Abbott and Costello do “Who’s on First” via satellite delay. And Colbert often uses Hoskinson as a character, too, calling over to “Jimmy” before clips, graphics or a camera change.

For example, in a regular segment called “The Word,” Colbert occupies the left side of a split screen, while Hoskinson calls for bullet points to appear one by one to his right, riffing off of Colbert’s topical rant like a snarky murmur in the viewer’s ear. A logical premise is taken to its absurd conclusion, and the graphic cue is the payoff.

“The window to hit the cue is very small,” says Hoskinson. “We refer to the bullet point as its own character, so we’ll say, ‘What would Bullet say here?’ There’s a right place for it to land and basically everything else is wrong; it either accents what Stephen has just said or counterpoints it. Our timing is critical. All the graphics are supposed to support Stephen’s performance in a seamless way, almost as if you’re having a conversation with somebody who’s replying quickly. The writers write word-specific scripts. Our job is to back them up with that level of precision, and help translate the written word into visual comedy.”

In another one of his favorite setups, Hoskinson employs a stack of graphics to block out the screen. For instance, in the early days of this year’s Republican primaries, he might have called cues for the heads of each of the nine potential candidates to clutter the screen one by one. The camera would continue to pan with each added graphic, so in the end there would just be room left for Colbert’s face to line up in the frame. “It’s a neat visual trick we rehearse carefully,” says Hoskinson, “but Stephen will put himself where he needs to be.”

In the control room with Demare, Hoskinson can call up to 100 graphics cues a night

And Colbert appreciates the execution. “Jim Hoskinson’s calm, patient intelligence I find very reassuring,” says Colbert of his director. “The fact that he is also funny I find threatening.”

very day is different and Hoskinson keeps his eye on what’s coming out of the writers’ room as the clock ticks toward the evening taping. Early in the day the writers digest and pitch bits about the current news so that by the 11:30 morning meeting, Hoskinson has a good idea of what to expect. But nothing is nailed down until the 1:30 read down, where choices are made for which scripts will play that day.

“After that, the day starts to get focused for me,” he explains, “and I need to know what props and set pieces we’ll have. That’s when I talk to our lighting director Mike Scricca, and stage manager Mark McKenna, to let them know where we’re going to be on the floor. By 3:30 or 4:00, things tend to firm up and we put out the rundown when the script is final. And around 5:15 or 5:30, we rehearse.”

Since a premium is put on live performance, as Hoskinson calls takes during rehearsal the interns and others in the audience provide a litmus test to gauge how the jokes are landing. Colbert stops periodically to give notes, largely on the various graphics, requesting changes to verbiage or the visual image. By this point, if a news story surfaces it’s rare for it to make it into the show.

“We’re interested in topical comedy,” Hoskinson notes, “but that starts early in the day. Those changes don’t come along at 4 o’clock. There are exceptions like when [then-South Carolina Governor] Mark Sanford came back and admitted he hadn’t actually been hiking the Appalachian Trail. That broke late in the day and we had to scramble with footage. Certainly, we have a short-term and a long-term focus on breaking news. For instance, the writers started working on the conventions two weeks ago. We try to get a head start on that, especially for the graphics team.”

After rehearsal, Hoskinson joins the writers and producers for rewrite, instant-messaging the changes back to his associate director, Yvonne DeMare, in the control room.

“Yvonne and I will be talking about what needs to be done,” says McKenna. “Then, when Jim comes out of the rewrite, there’s a lot of quick back and forth as to what’s ready and what’s not, and how much time we have before we have to go get Stephen [for taping].”

“A lot of changes come out of rewrites,” says Hoskinson, “but generally to graphics and the script. Stephen rehearses with the actual props we’re going to use in the show so that’s one thing we tend not to change, other than how it may be decorated. My job here is about figuring out how to accommodate the changes. That’s something we’ve learned is important. The control room and the studio all take a lot of pride in being able to adjust very quickly to what has to happen.”

An example of one of Hoskinson's 100s of graphics cues. Timing is essential.

An example of one of Hoskinson's 100s of graphics cues. Timing is essential.

While traveling to “cover” the political conventions is more the purview of The Colbert Report’s sister show on Comedy Central, The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, news events do sometimes take the Report away from the studio. The war in Iraq and the treatment of American soldiers has been a constant theme on the show and, for one week, it went on the road to Baghdad to tape before a live U.S. military audience. To do so, Hoskinson was part of an eight-person expedition in April 2009, to scout locations for a June shoot that would take 30 of The Colbert Report team to stage the show in one of Saddam Hussein’s former palaces. Hoskinson still brightens when he talks about it.

“We could only use what we brought in and had a production company in Kuwait supply the staging material. We knew we needed to have our usual ability to react as quickly as we normally would, and brought over some editing stations, but then we sent the show back to New York to have it re-edited for air.”

Another staple segment of the show, “Formidable Opponent,” in which Colbert argues with himself as if he were two pundits, cutting between cameras, digital effects changing the color of his tie between shots, proved to be a tough trick to pull off in Iraq because Colbert insists on doing everything live. “In our studio, the elements of the ‘Formidable Opponent’ background are married digitally, and we change between the two Stephens with one button,” says Hoskinson. “But for the audience in Iraq, our technical director, Jon Pretnar, had to figure out how to change each background element manually with a quick sequence of buttons. And, because he was short on equipment, each time he did it, he had to reverse the order from the previous change. I thought we were smart about accepting what we could and could not do technically. Those shows were once-in-a-lifetime experiences and the audience was really appreciative. We were proud to be able to do it.”

Sometimes it’s an uncanny experience when the show’s satire becomes a meta-element of the very world it’s parodying. The antics of both Colbert and Jon Stewart on The Daily Show provide frequent fodder for cable news pundits, and have, at times, drawn the hosts into in-studio or even cross-broadcast dialogue with the real news shows. It’s a balancing act to inhabit that space but not reveal the man behind the curtain. “One of the most enjoyable things about Stephen playing a character in the show, rather than being himself, is he gets to interact with the world in real ways. That’s why the super PAC works so well for us,” says Hoskinson.

“I would say that we want our comedy to be about something,” he continues. “It can be just silly or it can be more pointed, but with political humor there’s a lot to play on that people are interested in. I like to think that we have passionate fans, and they’re passionate in part because we’re talking about things that mean something. But the bottom line is that it’s a comedy show.”

Whether it’s blocking an in-studio bit, directing a live summer music festival on the USS Intrepid aircraft carrier docked off the West Side of Manhattan, or nailing the joke with a graphics cue, Hoskinson is clearly sparked by the variety of directorial challenges thrown his way.

“Jim is the perfect director for our show,” says co-executive producer Bennett. “He is incredibly talented, calm under pressure, and has great comedic timing. He is respected by everyone who works with him and has proven himself daily in the studio as well as on the road in Philadelphia, Vancouver, and Iraq. Jim recently directed the U.S. women’s gymnastics team with ease as they flipped their way through the studio to deliver Stephen a pen. Days before, he directed seven cameras for our concert series on the Intrepid between downpours. He can do it all.”