By Ann Farmer

Late in the afternoon on the last day of the Republican National Convention, veteran CBS news director Eric Shapiro got word that Clint Eastwood was indeed appearing that night as a surprise speaker. No one, however, said anything about a chair. Shapiro, who was directing the network’s coverage of the event, naturally took note of the chair placed to the side of the podium after the lights came up. But it took him another second or two to realize that whenever Eastwood craned his neck in that direction, he was improvising a conversation with an imaginary President Barack Obama plunked down in it.

“This is why you have to be flexible,” says Shapiro, who instructed his camera operator to open up the shot so viewers could get a clear view of what was happening. “The goal,” he says, “is to give the viewer the best seat in the house.” Whether he’s directing the CBS Evening News or special events, Shapiro, who is logging his 50th year with the network, has always pursued that same objective. “It’s our job to cover them accurately,” he says. “It’s not my job to make somebody look better than they are, or do something to improve upon how they appear or present themselves to us. It’s our job to cover them as professionally and with as good a quality as we can.” Just about everything else, though, that concerns directing political events—including debates, election night coverage and inaugurations—has changed over the years.

First of all, the networks used to show a lot more of the convention proceedings. “The networks had gavel to gavel coverage,” says Shapiro, who worked his first convention 40 years ago when Walter Cronkite was the CBS anchor. “They’d start in the morning, continue all afternoon, and return to it in the evening.” This year most of the networks only broadcast the final hour of each night on TV, but viewers were able to watch the entire convention online. In the past, it also took more effort to put them on the air. The equipment was bigger and bulkier and took much longer to set up. There were no computers or cell phones. “So you really had to be there,” he says, describing how CBS sent him to the convention sites with large contingents of production and crew members. They would often stay for three or four weeks to pull it off.

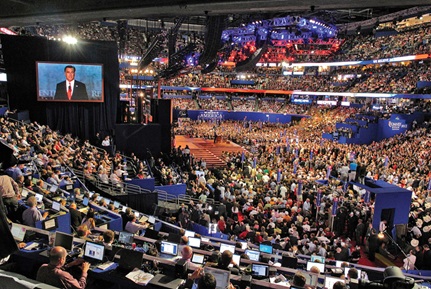

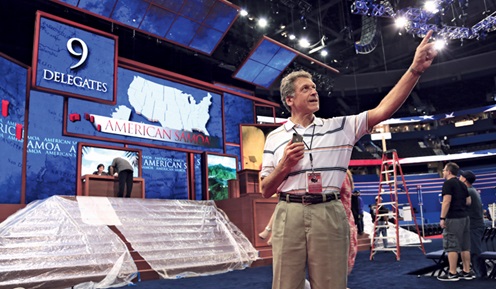

PARTY TIME: (top) Shapiro, who first scouted the location a year ago, says a large project like the Republican National Convention “requires a tremendous amount of attention.” (bottom) His goal at the RNC was to position the anchors so they had the best view of the floor. (Photo: (top) Getty/(botttom) NBC Universal)

PARTY TIME: (top) Shapiro, who first scouted the location a year ago, says a large project like the Republican National Convention “requires a tremendous amount of attention.” (bottom) His goal at the RNC was to position the anchors so they had the best view of the floor. (Photo: (top) Getty/(botttom) NBC Universal) “We built these huge cities to cover the events,” says Shapiro, recalling how they would roll in big, remote vans. The electrical technicians would wire everything onsite. Since 2004, CBS buys satellite time and multiple lines and sends all the camera feeds back to its news headquarters on 57th Street in Manhattan, where Shapiro and his control room team do the switching, insert the graphics, and direct the show. “It’s really different,” he says. “Being 1,000 miles away makes it impossible to soak up the ambiance.” However, he adds, “I’ve always felt comfortable looking at the world through a soda straw.” Shapiro still travels to the convention venues ahead of time to ensure everything is set up correctly, but with each cycle, he spends less and less time at that end. “It’s become a different sort of an exercise,” he says, in trying to quickly absorb as much as possible. He’ll squeeze in quality time with his camera operators, stage manager and others who stay behind onsite. “So when I come back to New York, I’m able to communicate in the shorthand that you normally develop when doing these shows.”

This year, for example, Shapiro directed the CBS Evening News in New York on a Thursday night, as usual. The following morning he flew to Tampa where the RNC was being held. He spent a day and a half overseeing the camera and anchor booth installations, blocking shots and working with the lighting and scenery crews. Shapiro is also responsible for the graphics on his broadcasts, so he took a variety of shots of the “CBS News Campaign 2012” logo embroidered onto a flag. He flew back to New York for Sunday rehearsals and to produce the bumpers, which were prominently displayed on the website and throughout TV broadcasts. The next day, he launched into the live coverage.

This compressed schedule is cost-efficient, but can be draining on Shapiro. Sometimes he takes red-eyes and goes without sleep. The one advantage is that he can go home at night and flop in his own bed. But even that isn’t much of a boon. When he used to direct onsite, he had the luxury of focusing single-mindedly. “Large projects,” he says, “require tremendous concentration.”

“Shapiro is not only organized and focused in creating the nightly broadcast, he’s able to quickly switch gears and work on the convention,” says associate director Scott Berger. “He’s the most focused person I have ever met.” It’s not surprising that Shapiro once aspired to be on-air talent. He speaks with the kind of clarity and sincerity that all good anchors evince. No “uh’s” ever seem to escape his mouth. Poised, decisive and levelheaded, he naturally engenders respect. “He is a true professional,” says associate director Bob Rooney, who admires Shapiro’s ability to foster a creative and productive environment for others to show off their craft, and make it fun too. “All of us on the floor and in the control room are struck by his enthusiasm, exuberance and passion for what he does,” says Rooney. “You learn something new every day just watching him.”

Shapiro began his broadcasting career in college when he landed a DJ slot on a jazz show on his college radio station. “I knew nothing about jazz,” he laughs. After college, he got his first job—where almost everybody at CBS begins—in the mailroom. At the time he was working alongside future singer-songwriter Barry Manilow. “If you want to be a musician,” he quips, “start in the mailroom.”

One day, when Shapiro was delivering the mail to the newsroom, one of his colleagues invited him to return later to the control room to watch them put the news on air.

“I walked into the back of a dark room with all these monitors, which was strange to me,” says Shapiro, who had not been inside a control room before. He found it mysterious, exciting and energized. “But there was something a little disorganized about it,” he says. “Until five minutes before the show, in bursts this very dynamic person who came in barking out commands and looking at monitors and shouting out things to people. He sat down and immediately took control. All the chaos came together and the show went on the air. I said to the other mail boy, ‘Who is that?’ He said, ‘That’s Don Hewitt. He’s the director.’ And I thought, that’s a really cool job. I think I’d like to do that some day.”

THE SET UP: (bottom, center) Shapiro checking a possible standup spot; working out seating at the anchor desk with his cameraman and head carpenter. (Photo: (top) Everett/(bottom) NBC Universal).

THE SET UP: (bottom, center) Shapiro checking a possible standup spot; working out seating at the anchor desk with his cameraman and head carpenter. (Photo: (top) Everett/(bottom) NBC Universal). Now, 50 years later, sitting in his office upstairs from CBS’ sleek control room, his computer pings constantly, alerting him to a mushrooming list of new messages. His bulletin board is slathered in press badges from almost every political convention he’s attended. He looks positively baby-faced in his first, now faded, badge from 1972. “You can see that at some point I grew a mustache,” Shapiro chuckles, referring to the photographic evidence on badges from four straight election cycles in the ’70s and ’80s. Sitting atop a table are four wooden cubes that display the number ‘2250.’ It has nothing to do with dates, he says. Turning the cubes, some panels reveal illustrations of the different types of nuclear weapons that the U.S. and the Soviet Union sought to reduce under the SALT II treaty. Altogether, the reductions totaled 2,250. The cubes were a visual device, a clever gimmick, that Shapiro, who was the new CBS News Sunday Morning director, created to assist the morning show anchors in explaining the complicated treaty. It also put him on the map with the rest of CBS’ producers. “After I did this project,” says Shapiro, “they were all coming to me and asking me to do the graphics for them.”

Over the years, Shapiro worked on almost every news program on the CBS schedule, including Face the Nation and 48 Hours—both of which he helped develop. He currently juggles dual responsibilities as both the director of CBS News special events since ’92 and director of the CBS Evening News since ’95.

One clear difference between directing news shows versus political conventions, he says, is control. “The convention is you covering someone else’s show,” says Shapiro, noting that the political parties determine the convention’s staging, speakers, and pace to the extent that every minute is accounted for. They tend to schedule just enough time for the networks to present an opening animation, an anchor greeting and maybe a quick whip-around of the reporters on the floor. After that, it’s back-to-back speeches, often peppered with a mini biopic of the candidate, before the final thunderous applause of the night. This situation leaves the networks little opportunity for their own individual reporting or production. Come election night, though, “it’s all ours,” says Shapiro. CBS’ election night coverage tends to be graphics intensive, requiring a tremendous amount of computer pre-programming. Shapiro and his teams also assemble a new set, concoct fresh camera angles, and include any number of visual devices to create an engaging program that viewers can easily follow.

Groundwork for the conventions begins almost a year ahead, when the parties hold their first media walkthroughs at the intended sites. “That’s the first look we get of what we’re in for,” says Shapiro. It used to be that CBS, NBC and ABC each set up their own cameras and unilaterally directed the convention, but with CNN and Fox added to the mix, there got to be too many cameras. That’s when the networks began taking turns providing a pool feed. The pool director gets first dibs at where to place the 15 or 16 pool cameras that provide the overwhelming basis of coverage for all the networks. CBS rotated into that slot this season, but the network receives no special benefit. The pool director operates independently and provides everyone the same three feeds: 1) An isolated shot of the podium speaker; 2) A request hotline—if, for instance, a director doesn’t have the ability to snag a decent shot of the First Lady, he might ask the pool director to temporarily grab that shot for him; 3) A switched feed, in which the director cuts back and forth among his assemblage of cameras.

THE SET UP: (top) Looking at the view from the main anchor booth camera. (bottom) In the control booth with associate director Bob Rooney (Photos: (top) NBC Universal/(bottom) Corbis)

THE SET UP: (top) Looking at the view from the main anchor booth camera. (bottom) In the control booth with associate director Bob Rooney (Photos: (top) NBC Universal/(bottom) Corbis) This could be a wonderful show on its own,” says Shapiro, who is a tad envious of the pool director’s freedom to utilize multiple cameras and other fancy gear without concern for rundowns, graphics, on-air talent, or getting off the air on time. In addition, the networks share a 24-hour, doomsday camera placed on a building overlooking the arena in the case of a natural or man-made disaster.

Each network is also allowed some individual cameras for their unilateral coverage. “I try to stay with our own cameras as much as I can,” says Shapiro, who, this year, in addition to his fixed anchor booth and reporter podium cameras, arranged for three wireless mini-cam operators to roam the floor as well as other camera crews ready to shoot portable shots in town. He also had crews shooting scene-setting material in the days before the convention began. “He is not just smart in his composition of shots,” says Berger, “he understands the innate drama and essence of a convention—how the expression on a candidate’s face, the tear rolling down a delegate’s cheek really matters. He doesn’t just get the shots, he anticipates them so he can bring the story home to the viewing audience.”

Shapiro likes to bring something new each time. This year, he found a 360-degree camera, which figured prominently in CBS’ coverage. He also put in a request to station three robotically operated cameras with very long telephoto lens. However, once they were mounted, the Republican party objected to their size and placement (some were literally over peoples’ heads) and Shapiro had to replace them with smaller gear in a last-minute scramble.

“Whenever he has a camera somewhere, it’s going to be able to get multiple shots,” says Rooney, describing how Shapiro familiarizes himself with each camera’s hardware, lenses and focal lengths in order to stretch them to their capacity. CBS News Executive Director Rob Klug says that Shapiro always goes the extra mile to make the network’s coverage stand out. When they were in Charlotte for the Democratic convention, for example, Shapiro mounted a camera behind the podium for a reverse shot. “Only Eric Shapiro mounted a camera there to get that awesome shot looking out over their shoulder,” says Klug. “It’s one of those things; it seeps into the broadcast. You can’t always tell what makes CBS news different from everybody else. But that is it.” Each director has their individual ideas about where to set up their anchor booths. But that doesn’t mean they get what they want. “In a situation like this,” says Shapiro, “there’s only one ideal spot.” The others, he says, are second best and so on. To avoid conflict, the directors pick numbers out of a hat to determine an order for choosing their preference. This year, for the RNC, Shapiro drew number five. “My first thought was, we’re really screwed,” says Shapiro, noting that the last pick is often awkwardly situated. Oddly enough, another director took what Shapiro thought was the worst and CBS wound up with an OK position. At the DNC, he also ended up in a good location, but it was two small suites. So to make the anchor booth appear larger, he shot it from the adjacent suite.

GAME FACE: (Top) The 2012 Democratic National Conventionin Charlotte. (Bottom) Shapiro gathers critical information ahead of time so he’s prepared for cutaways and reaction shots. “I try to not get too clichéd, but there are certain things you want to hit.”

GAME FACE: (Top) The 2012 Democratic National Conventionin Charlotte. (Bottom) Shapiro gathers critical information ahead of time so he’s prepared for cutaways and reaction shots. “I try to not get too clichéd, but there are certain things you want to hit.” “My way is always to position the anchor so that they have the best bird’s eye view of the floor,” says Shapiro, who avoids head-on shots of the anchor in the event viewers see a speaker on the podium and feel inclined to turn the channel. The directors also draw for the best spot to position their podium correspondents and workspaces (or ‘ready rooms’). “Either you draw the greatest spot or the not so greatest spot and work around it,” says Shapiro. “It’s not always obvious which is best. A lot has to do with how you cable into the arena. And how the technicians have to get the cables from your transmission point up to your anchor booth. All those things have to be taken into account.” Once the show is up and running, party members pay a daily spin visit to the networks. They inform the producers and editorial staff who will speak that night and when, and what the theme is. All of this is critical information for the directors who try to prepare ahead of time for cutaways and reaction shots. If the mother of the Democratic keynote speaker, Julian Castro, is going to be there, they want to know exactly where she’ll be seated so they can easily cut to her when, say, Castro speaks—as he did—about her sacrifices as a single mom. Shapiro often gets copies of the major speeches about 30 minutes beforehand, which helps him steer his cameras appropriately. “I try to not get too clichéd with that,” explains Shapiro. “Every time [the speaker] mentions an old person, I don’t want to cut away to an old person. Or every time he mentions minorities, to have a person of color. I try to be a little more generic and accommodating. But there are certain things you do want to hit. It just makes sense to.”

Sometimes party officials aren’t happy with the director’s decisions. “I know I’m doing a good job when I get the same complaint from both sides at the same time,” says Shapiro, explaining that criticisms are more likely to be leveled after a debate. “One candidate’s people might criticize the fact that you’ve done too may reaction shots of their candidate or not enough. Or too many cutaways of the other candidate and not enough cutaways of their candidate. Those are watched very carefully.” Shapiro once directed a White House interview between Dan Rather and President Clinton that elicited grumbles. “His people thought that Dan looked better than the president. I disagreed. I thought they both looked perfectly even and fine,” says Shapiro. “But everyone sees things from their own perspective, I guess. It’s important that you are being evenhanded and that you make sure that your lighting people and your camera people are being evenhanded. Because that’s our job.” Shapiro’s directing team for special events usually consists of four ADs. Two are situated in the control room and two in the tape room. Two PAs assist Shapiro with graphics. His stage manager, Lindsley McGrath, stays onsite to attend to the needs of the anchors and to communicate with Shapiro during the coverage. Everyone is “top notch,” he says. When the 1996 RNC was held in San Diego, Shapiro recalls how half his staff spent an evening in the emergency room after eating lobster salad that had sat in the sun too long. But his second team jumped into place and the show went on just fine.

Minutes before the airing of the final hour of this year’s RNC, Shapiro said his usual prayer and good wishes for everyone to have a good show. He clutched his lucky stopwatch, tarnished from years of sweat. Speaking into his mouthpiece to his camera operators, he offered a $10 bonus to anyone who nabbed a shot of a cheering delegate in front of the anchor booth. “I try to get them pumped up,” he says. And sure enough, he was out at least $20 or $30 by the end of the night.

With associate director Scott Berger

With associate director Scott Berger At this point in his career, Shapiro calls shots instinctively. “There’s a cadence; it’s not formulaic,” he explained, referring to making his cuts. “I hold a shot long enough for it to mean something.”

Two-box shots present a special opportunity. A favorite of his from the last election cycle involved then-vice presidential nominee Joe Biden in one box and his mother in the other. When Biden said something about his mom, she turned to someone seated next to her and clearly mouthed, “I remember that,” to the delight of viewers and Shapiro. “I was happy to capture that,” he says.

This round, he was pleased to grab a unique shot of Republican nominee Mitt Romney entering the arena shaking the hands of well-wishers. Romney’s handlers were keeping his exact entrance under wraps. But Shapiro always instructs his camera operators to case the halls for undiscovered potential shots and one of them stumbled across the black shrouded entryway that Romney used. (10 more bucks for the camera operator!)

“So again,” says Klug, who was in the control room and jumped up with excitement when he saw it, “we were the only network to have that shot. Everybody else was sitting back waiting for the pool to get it. But when you saw that shot in the control room that day, it was amazing.”

It used to be that when the balloons were released, the end was near and Shapiro could heave a sigh of relief. He says now when he hears the balloons being blown up during the setup, he feels a pang of nostalgia. Nowadays, though, the balloon drop simply means that he and his team must prepare to switch gears. The network provides 30 minutes of special anchored, online coverage before and after their TV coverage.

Shapiro tends to pick more behind-the-scenes shots for the online shows. He predicts that the next evolution in directing political events will have even more to do with the Internet. “Going forward, it’s going to change things a lot.”