BY STEVE POND

ON THE RISE: (below) Kazan

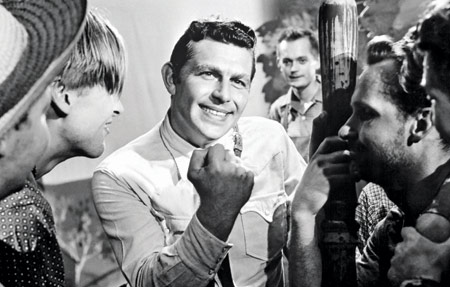

ON THE RISE: (below) Kazan used deep focus to show Lonesome

Rhodes (Andy Griffith) and his producer

(Patricia Neal) in the same shot in a radio

studio. "Every frame is layered," says Roach.

In his autobiography, Elia Kazan wrote that screenwriter Budd Schulberg “anticipated Ronald Reagan” in his script for Kazan’s 1957 movie A Face in the Crowd. As Jay Roach sits back to watch the film in his Santa Monica office, he points out that Schulberg and Kazan anticipated more than just Reagan in their underappreciated movie about the rise and fall of a cantankerous drifter whose corn pone and calculatedly homespun wisdom makes him a TV star and an unexpected political force. They also anticipated laugh tracks, applause machines, the use of television as the essential medium for political image-making—and the rise of a certain vice presidential candidate who served as the subject of Roach’s HBO movie Game Change.

“I think he did anticipate Ronald Reagan, but Sarah Palin even more,” says Roach, who studied A Face in the Crowd before making Game Change, his previous HBO movie, Recount, and his recent politically-themed comedy The Campaign. “Sarah Palin is kind of a female version of the character, and the film did inspire me in terms of how a phenomenon like that could occur.”

In Kazan’s film and in Andy Griffith’s fierce, exuberant performance as Larry “Lonesome” Rhodes, Roach says he found an incisive look at how mass media has come to dominate politics, and how eager today’s audiences are for a savior. “This movie, to me, was extremely influential in showing how somebody like Palin captures that adulation,” he says. “It really takes that notion of populism as a superpower, and turns it into a pretty strong indictment of the gullibility of the population to be won over by the anti-intellectual and anti-elitist. It’s a satiric statement about our desire, especially in chaotic times, for a charismatic person to step up and become someone onto whom we can project all our hopes and dreams. And then that person is bound to be caught up in the glow of affirmation, so you get a kind of co-dependent relationship between the needy audience and the person who will happily keep taking all that adulation.”

The film opens with a bustling small-town square in Arkansas—checkers players over here, whittlers there—each scene bursting with humanity. “Kazan fills the frame with people all the time,” Roach says. “Every frame is layered with foreground, midground and background people, and the extras casting is perfect. Your eye is so busy that you’re not thinking you’re in a movie, you feel like you’re in that world. I’ve tried to do that in a number of my films—on Recount and Game Change, we tried to fill the rooms so you couldn’t even see the sets because of all the people.”

Kazan first introduces radio producer Marcia Jeffries (Patricia Neal) as she’s going to the local jail to find subjects for her radio show, “A Face in the Crowd.” The prospect of a few days knocked off his sentence persuades Rhodes (whom she dubs “Lonesome” to his amusement) to sing a song and spin a few tales—enough to make the boisterous, larger-than-life character an immediate hit.

“Andy Griffith was not an experienced actor—he was a comedian, and this was his first role of any significance,” says Roach. “You think of Kazan as a guy who was all about trained actors, and I think 21 of his actors were nominated for Academy Awards. But he was also interested in mixing actors with non-actors, and he got a phenomenal performance from Griffith.”

After Rhodes gets out of jail, Marcia persuades him to do a morning radio show. As they talk in Rhodes’ hotel room, Kazan casts stark, theatrical shadows across every frame; in the radio station, Rhodes sits in one room with a microphone, while Marcia watches through the window of an adjoining room, and other people watch from rooms further in the background.

PEOPLE'S CHOICE: Griffith was a comedian, not an experience actor, but his fierce, exuberant performance offered an incisive look at how mass media has come to dominate politics.

PEOPLE'S CHOICE: Griffith was a comedian, not an experience actor, but his fierce, exuberant performance offered an incisive look at how mass media has come to dominate politics.

“He shot with enough f-stop that the focus lets you see all those people reacting in the background,” Roach says. “Some people would rack focus, but Kazan didn’t—he just used the depth of field that existed in the shot, and lets you participate however you want. I’ve noticed it with Mike Nichols too. It seems to be a theatrical director’s instinct to give the audience choices in every frame, instead of using coverage to force them where to look.”

In short order, Rhodes plays hard-to-get with a theatrical agent from Memphis, woos Marcia without much success, gets a Memphis television gig, and bids farewell to a mob of admirers as his train pulls out of the small town in Arkansas. “This is a great shot,” says Roach as Kazan’s camera hangs off the side of the train, shooting from just in front of Lonesome Rhodes, watching him shout goodbyes to his adoring fans, until they’re all left behind at the station and he’s simply staring into the darkness for an audience that isn’t there. “I love the way he stuck the camera out there to absorb the mass adulation—all those people radiating back to Lonesome Rhodes everything that he thinks about himself, that he’s God’s gift to humankind. And then it ends on this shot where he’s looking down the road, he’s run out of people and he’s not having as much fun. The minute the applause dies down and you’re alone, the self caves in and the propped-up person is shrunken back.”

In Memphis, Rhodes and Marcia meet Mel Miller, a college-educated television writer played by Walter Matthau. In his first television appearance, Rhodes plays up his country naiveté, turns the monitor around so that the audience can see what he’s looking at, and then brings out an African-American woman who lost her home in a fire. He’s a hit, but he’s also arrogant enough to mock the show’s sponsor, who pulls his support. To keep Rhodes from quitting and leaving town, Marcia reels him back in by kissing him, then following him into his hotel room. “It’s such a complicated, masochistic but strong move,” Roach says. “She realizes he’s so needy that the only way he’ll stay is if she gives him that something that boosts his ego again. It’s a craven move on her part, so now her soul is really at stake. But she also needs love, and she’s under the spell too.”

The film gets exuberant and comic when the makers of a “vitality pill” called Vitajex enlist Rhodes as a spokesperson. The pitch session turns into a wild, increasingly broad comic montage of Vitajex commercials. Rhodes chews a pill and laughs demonically, “Ooh-wee, I am ready!” He sings a song, and suddenly he’s surrounded by women in bikinis. A downcast animated pig with a droopy tail takes a Vitajex and turns into a big bad wolf with a tail that stands upright. A Marilyn Monroe type coos Vitajex’s praises from her bed.

“She’s having an orgasm, he’s having an orgasm, everyone’s having one giant orgasm,” laughs Roach. “This is a really funny, super-stylized, exaggerated comedic thing that has grounding and satirical power because it’s very close to the way advertising works.”

The campaign does so well that Rhodes meets up with the company’s owner, a conservative businessman, Gen. Haynesworth, who says he wants to introduce Rhodes to an up-and-coming politician, Sen. Fuller. “Shucks, general, I’m just a country boy,” demurs Rhodes. “Young man, never forget Will Rogers,” says the general. “He was just a gum-chewing, rope-curling cowboy, but he got to where he was telling off presidents and kings.”

With the general’s backing, Rhodes does rise to become a Will Rogers-esque superstar, in a montage of magazine covers, ceremonies and finally a literal rise—to a penthouse suite on the top two floors of a swanky New York hotel. “This is the most theatrical set in the movie,” comments Roach of the spacious and dramatic penthouse set, the opposite of the humid, enclosed Arkansas rooms he came from. “It’s fascinating, too, because it’s at the end of the second act, when he’s got everything he wants, but he’s reached this place where it’s not satisfying. He’s in a constructed world now. There’s open space, as opposed to the claustrophobic, hot, white Arkansas spaces. The design is a fantastic demonstration of where he’s come from contrasted to where he is.”

CO-DEPENDENT: Rhodes shouts goodbyes to his adoring fans, until they're all left behind at the station and he's left alone. Anticipating current politics, Kazan understood how eager the public is for a savior

CO-DEPENDENT: Rhodes shouts goodbyes to his adoring fans, until they're all left behind at the station and he's left alone. Anticipating current politics, Kazan understood how eager the public is for a saviorLonely even though he’s surrounded by sycophants and willing women, Rhodes asks Marcia to come over late at night. He’s as downcast as we’ve ever seen him, standing on the balcony in his bathrobe and looking at a forest of TV antennae as a guitar plays a mournful version of “Sittin’ on Top of the World.” He proposes, and she seems to accept—though her only real comment is “don’t hurt me.”

“The film goes to such a great place here,” notes Roach. “You’ve been wooed by the film, you’re enjoying the comedy. Now it really starts getting more and more dark. Literally—there’s less fill light, the sides of people’s faces are allowed to go completely dark, even the eyes are allowed to go dark sometimes.”

But like Rhodes, the film has mood swings. Quickly, we’re back in the bright penthouse daylight as Rhodes shows off his newest invention: a “reaction machine” that supplies laughs, giggles and rapturous applause at the turn of a dial. “He’s got a machine that laughs and applauds whenever he needs it, so his life is a big, fake, fraudulent thing. Dr. Evil [from Roach’s Austin Powers movies] would love a machine like that.”

For Roach, the movie becomes disturbing when Rhodes goes back to Arkansas to judge a baton-twirling competition, and revels in the nubile contestants squealing and pawing at him. It is, the director says, a typical temptation available to politicians: “How many politicians have we lost to this feeling that you’re above the rules and you deserve this kind of adulation? This scene is a fantastic representation of what happens with so many politicians, and we definitely tried to go this way with Will Ferrell’s character in The Campaign.”

But Rhodes goes further than just a dalliance: He goes to Mexico and marries baton twirler Betty Lou Fleckum (Lee Remick in her film debut), leaving Marcia crushed. Roach jokes that the televised wedding afterwards foresaw the likes of The Bachelor.

Rhodes, meanwhile, has bigger plans than just celebrity. In another scene that leaves Roach marveling at the skill of Kazan’s background casting, he becomes a spin doctor and political coach who tells the stiff politician, Sen. Fuller, how to become a faux man of the people. “The film becomes more political as it goes along,” says Roach, “because now the celebrity is being harnessed, just like people now harness celebrities for politics to achieve partisan political objectives.”

As Rhodes glories in his new clout (“I’m not just an entertainer, I’m an influence!”), Marcia, who has hung around to run his company for a 50 percent cut, sinks into a darker place. Miller finds her at the end of a dark bar, dressed in black and half in the shadows. On a TV screen above the bar, Rhodes prompts his special guest Sen. “Curly” Fuller with a softball question about Social Security, and Fuller responds with a down-home homily about government handouts that would sound perfectly natural on the current campaign trail.

AFTER THE FALL: Rhodes rages on the balcony of his New York penthouse. The most theatrical set in the movie reveals the scale of his loneliness.

AFTER THE FALL: Rhodes rages on the balcony of his New York penthouse. The most theatrical set in the movie reveals the scale of his loneliness.Marcia soon faces Rhodes in another dark scene, this one taking place in her apartment late at night. Rhodes has caught his wife and agent together; he sends them away and then runs to Marcia, screaming about how he needs her and how Sen. Fuller is planning to create a new cabinet position, Secretary for National Morale, just for him. He rants that a big banquet following his show the next night will be the kickoff for his newfound political clout, which is bound to land Fuller in the White House. “This whole country’s just like my flock of sheep!” he screams.

“There are few films that deal with the narcissistic personality disorder this way,” says Roach. “I’ve been around those narcissistic rages, and this really captures how narcissism turns into misanthropy, a contempt for the audience, because you resent being at their mercy. And in the middle of this shadowy, shadowy room, Marcia finally stands up for herself.”

Not only does Marcia walk out on Rhodes, she comes back to the studio at the end of his program the next day—just in time to turn up the sound on Rhodes’ microphone, which he thinks has been cut during the final credits. In place of the genial country boy they see on television, viewers hear a different Rhodes, mocking the “morons” watching at home: “I can take chicken fertilizer and sell it to ’em as caviar. I can make ’em eat dog food and think it’s steak.”

“This is very carefully edited—it’s very clear storytelling of a complicated idea,” Roach says. “That’s a hard bit of staging. I don’t know if he storyboarded it, but I’m sure he shot-listed it in detail.”

As Rhodes goes down in the elevator after his show, his career goes down in flames—and by the time he gets home for his power dinner, all the guests have canceled. Marcia and Miller pay Rhodes one last visit in his penthouse, where he rages, drunk and accompanied only by the sound of his applause machine. “These are great shots, capturing the scale of his loneliness,” says Roach of the scenes in which Rhodes stands alone on his balcony. “This is just classic narcissistic rage, pure paranoia, pure evil.”

Marcia tells Rhodes that she was the one who turned his microphone back on; utterly defeated, he sends her away. As she and Mil-ler stand in the street below, they hear him screaming, “Marcia, don’t leave me!” from high above. “You were taken in, just like we all were taken in,” Miller says. “But we get wise to him. That’s our strength—we get wise to him.”

Watching the final scene, Roach grins. “It just occurs to me that this scene is similar to [campaign manager] Steve Schmidt and John McCain at the end of Game Change,” he says. “Steve Schmidt went through the same arc that Marcia goes through in this story: He thinks by introducing Sarah Palin to the people he can help this guy, John McCain. But by the end he realizes he’s made a deal with the devil.”

Just before “The End” appears onscreen, we watch a cab drive away as a giant Coca-Cola sign flashes and Lonesome Rhodes screams out through the night. “He’s completely gone to hell, and she’s willing to climb out of hell,” says Roach. “What a great way out.”