BY DAVID KRONKE

Jorn Winther was taken from his production truck, hands in the air, Secret Service guns trained on him. Winther, David Frost and the rest of Frost’s crew were escorted to the basement of the home where Frost was conducting his historic series of 1977 interviews with former President Richard Nixon.

The fact that the home, in an Orange County gated community, belonged to friends of Nixon, didn’t matter to Secret Service agents. What did matter was the munitions cache they had just discovered in the basement (the homeowner was a gun collector), even though they had ostensibly thoroughly searched the premises before the interviews had begun.

“No one had bothered to open those closets before,” says Winther, who directed the landmark series of interviews, which still holds the ratings record for a political interview (the first installment attracted 45 million viewers). “They had checked the house out three or four weeks before we went there, but nobody ever opened these things. They were surprised. Their concern was that any one of us could have taken a rifle and shot Nixon.”

Being held at gunpoint isn’t usually within a director’s job description, particularly when directing an interview with the former leader of the Free World. But it’s a measure of what a significant event it was that a mere series of interviews inspired both Peter Morgan’s Tony award-winning stage play Frost/Nixon and Ron Howard’s Oscar-nominated film adaptation of the play.

Still, Winther says with a self-deprecating laugh, “I didn’t do a fantastic job of directing; it wasn’t like there were helicopter shots. Someone out of college could’ve directed this. The only difference was, this was important.”

.

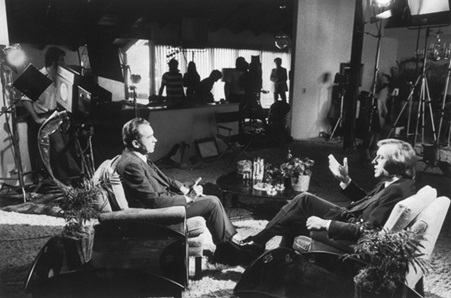

CONFESSION: Winther wanted to keep the emphasis on Frost and Nixon’s faces, not call attention to the directing. (Photo credit: John Bryson/Getty Images)

CONFESSION: Winther wanted to keep the emphasis on Frost and Nixon’s faces, not call attention to the directing. (Photo credit: John Bryson/Getty Images) The 82-year-old, Danish-born director is a real-life Zelig: He met The Beatles backstage during their first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show and later produced a special that reunited former Beatles John Lennon and Paul McCartney— though they refused to perform together. “If they had, I’d be lounging in the Caribbean right now,” laughs Winther. Frost hosted that special, which led to the invitation for Winther to direct his interviews with Nixon.

In addition, Winther worked for President John F. Kennedy and, later, met Bobby Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles not long before his assassination. Keith Richards teased Winther for refusing to smoke pot with the Rolling Stones. He roomed with the late ABC news anchor Peter Jennings when they moved from Canada to New York. He accompanied Walter Cronkite to the Soviet Union for an interview with Mikhail Gorbachev. And what’s more, his four children followed him into the business and are members of the Directors Guild.

But Winther’s most memorable accomplishment was his work on Frost’s unexpected outsmarting of Nixon in a series of interviews, during which the former president shakily and shockingly declared, “When the president does it, that means that it is not illegal.”

The interviews came at a time when Frost was considered an irrelevant lightweight. “David’s reputation was down; he was almost out of the business,” Winther recalls. “He was doing stuff like The Guinness Book of World Records.” Nixon, meanwhile, was hurting financially due to legal expenses. Frost offered Nixon $600,000 and 20 percent cut of the profits for the interviews; American broadcast networks refused to engage in what they dismissed as “checkbook journalism.” “Nixon thought he could outsmart David, because David was known as a soft interviewer,” Winther says. “He figured he could outwit him. Both men had a lot at stake.” Winther recalls Frost and his team being so excited they missed the exit while driving to Nixon’s San Clemente home. “We were all awed to meet him, even though we were all liberals,” he says. Nixon had ordered background checks on Frost’s team and knew Winther was from Denmark; during a break in the meeting, Nixon took him to a globe and pointed out Denmark.

“‘Four million people—not very important as far as the world is concerned,’” Nixon told him, Winther recalls, adding, “‘And here,’ he said, turning the globe, ‘is the real problem—China. If we don’t make friends with China, they’re going to go past us. They’re going to conquer the world, and they’re going to be far ahead of us economically.’ That was 1977. And he was right. People forget he was very astute internationally. He seemed to have a real passion for that.”

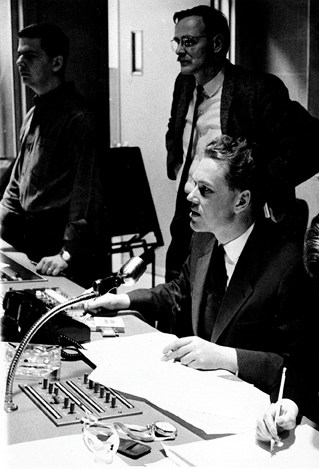

HIGHLIGHT: Winther has been in the business for decades but his most historically memorable work was on the Frost/Nixon interviews when Nixon apologized to the

HIGHLIGHT: Winther has been in the business for decades but his most historically memorable work was on the Frost/Nixon interviews when Nixon apologized to the

nation for his role in Watergate. (Photos courtesy Jorn Winther)

Nixon wanted the presidential seal between him and Frost during the interviews. Frost’s team vehemently disagreed. Winther jokingly suggested the flag of Denmark, which disarmed Nixon so much he laughed and approved a compromise: a bookcase.

“We wanted something neutral in the background behind them,” he explains. “We wanted the emphasis to be on their faces and their discussion. We didn’t want people to come away from this saying, ‘Wow, that was really well directed!’ We wanted to focus on their faces and the questions and the answers. I feel that way about the director all the time—he’s there to be the storyteller; he’s not there to be noticed. A lot of directors don’t think that way, but I do.”

Initially, the interviews were going to take place at Nixon’s home, but radar from Coast Guard ships in the nearby Pacific Ocean disrupted the production feed. Recalls Winther, “Nixon said, ‘Oh, I can get rid of that,’ and he made a phone call, and he couldn’t get rid of it—he forgot he wasn’t the president. When he made a phone call in the past, the Coast Guard moved, but they didn’t move for him anymore.” Hence, the change of location to that well-armed gated community.

Winther says his other big contribution to preproduction was tracking down the perfect chair for Nixon, a move that proved subtly important.

“We wanted a chair he could sit in forever,” he explains. “We didn’t want any intermissions where he would get up and go talk to his team. We didn’t want them coaching him too much. The extraordinary amount of time we spent looking for that freaking perfect chair was unbelievable. When I think about it, it’s crazy.”

The interviews took place over 12 days, consuming at least two hours a day. Winther set up three cameras: One focusing on Nixon, one on Frost and the other a two-shot of both men (and that bookcase). He monitored the entirety of the interviews from a production truck outside the house, entering only when he heard a frightening pop inside the house. “We thought, ‘Oh, my god, he’s been shot!’ and rushed in the living room. A bulb in the lighting had exploded.”

That errant light bulb unnerved the Secret Service so much they re-searched the house and found the arsenal that resulted in them pulling guns on the Frost team.

Frost saved Watergate for the final interview and had a crack team of researchers thoroughly prepare him, which resulted in Nixon’s emotional mea culpa, a surprise to even Frost’s crew. “At the beginning, everything was nice, and everyone got along well, but it got testy because David was extraordinarily well-prepared,” Winther recalls. Nixon had no access to questions beforehand.

“The last interview we taped was on Watergate, and that’s where he broke down. It was momentous for everybody,” he adds. “He said he wanted to apologize to the American people. There was something really important going on there. You realized, ‘This is going to go throughout the world.’ That’s why there’s a play about it, and a movie, but we didn’t really know how historic it was at the time.”

Winther says the toughest part of his job was overseeing the editing alongside Don Stern. They spent “four or five nearly sleepless weeks” assembling 28 hours of footage from three separate cameras above a dubious massage parlor on Cahuenga Boulevard in Hollywood. “Two weeks in, the massage parlor caught fire, and had we been on the ground floor, the tapes could’ve been destroyed,” he remembers.

Another challenge was plugging leaks—crew members were being offered up to $80,000 to provide advance clips. (Journalists disguised as gardeners gained access to the gated community, but none made it as far as the interview site’s front door.)

Winther admits he was tempted to fudge on the editing—to cut to Nixon’s reaction shots out of context to make him seem even shadier—but common sense prevailed. “It was a great temptation, because that would’ve been bad for him. We knew he was being dishonest at times, and it would’ve shown him being dishonest, so we certainly considered it,” he confesses. “In editing, we could’ve changed history, we could’ve made this guy look really, really bad. It was very difficult not to do it, and I wouldn’t say this to you had we actually done it. Even David at times asked, ‘Don’t we have a better reaction shot?’ Nowadays, everyone does it.”

In the end, the interviews resuscitated Frost’s reputation and further collapsed Nixon’s, though Winther confesses, “Much as I disliked Nixon, I had a grudging respect for him once we were done.” Winther never saw a production of Morgan’s play but liked Howard’s film, although points out the scene in which Nixon drunk-dials Frost is “totally, absolutely bullshit.”

Yet, for all his contributions, Winther remains bemused to this day that in Frost’s memoir, he is relegated to but a sentence in the account of the signal achievement of Frost’s career.

“David is very good to work with,” Winther says, while drolly adding, “He doesn’t give a hoot about directing, and he didn’t give us any credit, either.”