DVD Classics

By Robert Abele

Few Hollywood filmmakers have been as tied thematically and narratively to the depiction of political concerns as John Frankenheimer. But what’s most arresting about this association is that the movies he made on the topic over his six decade career—from The Manchurian Candidate in 1962, right up to his last film, the Lyndon B. Johnson/Vietnam-centered Path to War, which premiered on HBO just before his death in 2002—are hardly classifiable. Some approach politics as a ruminative character study; some are issue-driven stories; and a few are grand thrillers with undertones of politics.

Frankenheimer’s beginnings in live television during the 1950s gave him the best possible introduction to the potential impact of a well-told, on-camera story of political machinations. In a broadcast apprenticeship with legendary journalist Edward R. Murrow that included a stint as an associate director on See It Now, Frankenheimer was there for the landmark installment when, using clips and recorded speeches, Murrow dismantled Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Cold War fear-mongering. It’s an experience that surely fueled Frankenheimer’s desire to make the most out of a big screen adaptation of Richard Condon’s 1959 satirical novel The Manchurian Candidate, about an outlandish Communist brainwashing plot to turn a model American soldier into an assassin.

The Manchurian Candidate (1962)

The resulting film, considered the granddaddy of political conspiracy thrillers, is justly hailed for the way Frankenheimer used a variety of techniques—black comedy, surrealism, both big and quiet performances, cross-cutting suspense and even a jangly karate fight between Frank Sinatra and Henry Silva—to walk a high wire of storytelling plausibility. Between the stylistic extremes, though, nests a sometimes underrated portrait of politics in the modern age. Let’s not forget that the literal “Manchurian candidate” is not brainwashed Korean War vet Raymond Shaw (Laurence Harvey), who is being induced to murder by his Machiavellian mother (Angela Lansbury). It’s his mother’s husband, Senator John Iselin (James Gregory), a superficial demagogue in the McCarthy vein, who needs no advanced brainwashing methods to be the ideal political pawn—just a craven, theatrical bent and the laserlike focus of his traitorous wife.

Iselin’s rise stems, as McCarthy’s did, from shouting “Communists!” in a crowded chamber, and it’s the character Frankenheimer is particularly merciless in skewering. The scene in which Iselin interrupts a televised press conference with the Secretary of Defense to grandly accuse him of harboring communists, he frames Iselin’s back-and-forth with the Secretary against the camera crews’ televisions in the foreground, which carry Iselin’s battle cry in real time. (Frankenheimer directed the live TV parts from a television truck off set, calling out the edits we see on the monitors as they were happening.) Staging an event and its immediate broadcast in the same shot is a shrewd way to show the dimensional comparison between words yelled in a room versus a message beamed to millions: the real figure is small (and small-minded), but the medium is too big (and too multiplied) to ignore. Later, screenwriter George Axelrod and Frankenheimer add a stinging comedic touch to the Senator’s made-up number of Soviet-controlled moles by cutting from Iselin plopping Heinz ketchup—a company that boasted 57 varieties—on his plate, to a shot of him alerting the public to exactly how many card-carrying communists there are in the Defense Department: 57!

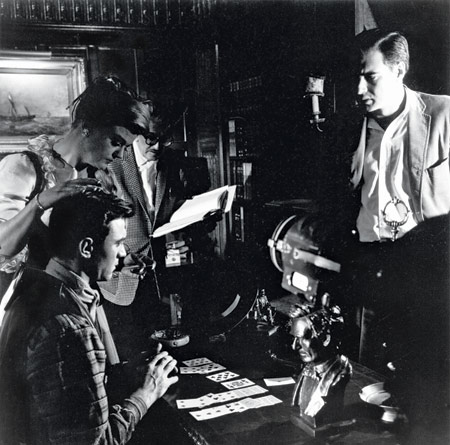

The director also wittily uses images of Abraham Lincoln as ideological counterweights to the Iselins’ dishonest political scheming. First, Frankenheimer opens a scene between Lansbury and Gregory with a framed portrait of Lincoln in the background, on which Iselin in a bathrobe is reflected like a hollow stain on a great man. Later scenes feature either that portrait in the background, or a bust of the 16th president in the corner of the screen. These directorial touches—which culminate in Iselin awkwardly, hilariously dressed as Lincoln himself at a costume party—are both sly commentary and foreshadowing, considering how the character winds up.

The Manchurian Candidate may have been sparked by ’50s-era McCarthyism, but its initial legacy seemed regretfully tied to an unforeseen political tragedy that took place after the film’s release: the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963. (The documentary-like nature of the violently climactic political rally scene owes mostly to Frankenheimer’s studying of convention newsreels, but now it mostly resembles—presciently—the herky-jerky effect of the Zapruder footage.) It’s impossible to say if Frankenheimer would have gone ahead with his second corridors-of-power thriller, Seven Days in May, had it come to fruition after JFK’s death. (Filmed in 1963, it was released in 1964.) But we should be grateful he did, because the adaptation of Fletcher Knebel and Charles W. Bailey II’s popular novel expertly dramatizes another disturbing Cold War conspiracy, albeit one more realistically imagined and home grown: What if a right-wing four-star general (Burt Lancaster), the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, decided our elected leaders weren’t competent enough to protect the country and took matters into his own hands?

Seven Days in May (1964)

In the agitated opening moments, Frankenheimer makes unnervingly clear the political division in the country during the Atomic Age as protesting ban-the-bomb types and hawks come to blows outside 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. It’s the real White House, too: Kennedy press secretary Pierre Salinger, who’d become friendly with the director and expressed to him the president’s desire that Seven Days in May be made (since it depicts a level-headed, coup-vanquishing Commander-in-Chief), is said to have arranged for Kennedy to be in Hyannis Port the weekend Frankenheimer wanted to shoot in Washington.

Inside the halls of government and private spaces, though, the director makes solid use of his penchant for dynamic depth of field to ratchet up the feeling of lurking peril. As Kirk Douglas’ puzzled Marine colonel sits down at home, alone, to watch Lancaster give a jingoistic, rabble-rousing speech to an adoring crowd, Douglas’ head is in the foreground while the television is reflected in a mirror behind him. The squawking box—once again, in Frankenheimer’s hands, an object of worrisome propaganda—acts almost like a thought bubble for Douglas, who has begun to suspect his superior officer of plotting to overthrow the president (Fredric March). Once Douglas airs his concerns in the Oval Office, Frankenheimer frames March in the hallway quietly conversing with his skeptical aide (Martin Balsam) about the far-fetched plot they’ve just heard. Both of them are in shadow, but the small figure of a cleanly lit Douglas is centered in the background between them, waiting for an elevator. Seeming to contradict Hitchcock’s belief that audiences always go to the larger objects in a frame, it’s Douglas we look at, as if to indicate that his character has planted the notion successfully in their—and our—brains.

George Wallace (1997)

It would be many years before Frankenheimer dived back into American politics on the screen, but he would get involved in it for real in the ’60s as a close friend of Robert F. Kennedy’s, close enough to have driven Kennedy to the Ambassador Hotel the night he was assassinated on June 6, 1968. Frankenheimer later said in interviews that it could very well have been him alongside Kennedy that fated night—Kennedy wanted him there—but the director, always considering the power of the image, decided it wouldn’t look good to have a Hollywood figure seen next to Kennedy.

By the time Frankenheimer, who was a national vice president of the Guild and a seven-time DGA Award nominee, was ready to revisit the hullaballoo of American politics and those who operate in that sphere, he would be in a career resurgence thanks to television, the medium he began in, and the one so often depicted as a solemn tool of communication for rascally politicians and statesmen alike. His 1997 biopic George Wallace, made for TNT, would be his most expansive look yet at a political life: the lightning-fast rise and precipitous fall of the infamous governor of Alabama, played by Gary Sinise with an impressive grasp of the cagey ferocity that embodied segregationist populism. “Wallace is the Faust of our generation,” Frankenheimer said in an interview, “a tragic hero who sold his soul.” The director didn’t skimp on the ugly racism of the era, with jarring black-and-white recreations of civil rights unrest driving home the physical repercussions of a firebrand’s divisive rhetoric. But because Wallace was also a redemptive figure in the wake of an attempt on his life and a transforming religious conversion, it allowed Frankenheimer to make the most out of a climactic scene—partly invented, but true in spirit—in which Wallace makes his way into Martin Luther King’s old church and confesses to a sea of black faces. Softening his usual technique of facial close-ups, Frankenheimer lets this sacred space breathe as the wheelchair-bound, broken Wallace, sometimes diminutive in the frame, seeks a measure of forgiveness.

Path to War also seeks sympathy for a fallen man, decades after the fact, in this case President Lyndon B. Johnson and the Vietnam War he escalated at great cost to his legacy of good works. In Frankenheimer’s dramatization, and Michael Gambon’s portrayal, the president’s acquiescence to the general’s “bomb-bomb-bomb” counsel seemed to clearly eat at him. This is a men-talking-in-rooms movie with the soulful peril of one of Frankenheimer’s thrillers. The director’s taste for jittery camera moves may have been retired, but he still displays his affinity for deep focus handling of people in a frame—foreground and background heads in a power struggle for who has the upper hand—leading to some of his most sublimely powerful compositions yet. Path to War is perhaps his most artful attempt at the kind of dignity-stripping character study that seemingly only American politics can produce in its compromised leaders. In the rubble of the 1960s, Frankenheimer found something more immediately gut-wrenching than brainwashed soldiers, treacherous military men or rabble-rousing racists: A well-intentioned man driven to give up the position he’d worked his whole life to attain. What makes it doubly poignant is that the end of Path to War—LBJ at his desk, announcing to the nation that he would not seek re-election, and the somber moments after the cameras turn off—also marked Frankenheimer’s graceful exit as a true master of political moviemaking.