BY AMY DAWES

Photographed by Scott Council

Politics, media and comedy have become so entwined that it’s hard to remember a time when we didn’t have fly-on-the-wall, fast-paced, behind-the-scenes television series like The West Wing, Sports Night and Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip to show us how it looks from the inside. Director Thomas Schlamme had a role in all three.

Though his groundbreaking style would push the camera where it hadn’t gone before, Schlamme started in the business as a decided outsider, directing concert films (Bette Midler) and comedy specials (Robert Klein, Whoopi Goldberg), before moving into episodic television (Mad About You, It’s Garry Shandling’s Show), directing pilots (Parenthood, Mr. Sunshine, Pan Am), and a long-lasting collaboration directing and executive producing three shows with Aaron Sorkin. In his worldview, absurdity and profundity mingle easily, allowing him to move freely from comedy to drama—a factor in his receiving unprecedented DGA Award nominations in 1999 in both categories (and winning for Sports Night).

Schlamme says he remains committed to developing politically-oriented material, citing the 2004 dramatic series Jack & Bobby (he directed an episode and executive produced), about how two teenage brothers are molded by their life experiences, turning one into a future U.S. president. His latest project is a potential series about the men who developed the atomic bomb at the Los Alamos Laboratory and their dawning realization of the impact the weapon would have on the world.

When we met in his Shoe Money Productions office on the Sony Pictures lot, Schlamme was recovering from recent knee surgery and eager to get back on the basketball court. He spoke frequently about on-set politics, and his commitment to protecting the creative rights of episodic directors as a longtime member of the DGA National Board, Western Directors Council, and Television Creative Rights Committee. We began by discussing how one handles a fictional depiction of the most political territory of all—the White House.

AMY DAWES: Let’s get right into the pilot for The West Wing. There’s a memorable tracking shot near the beginning when chief of staff Leo McGarry (John Spencer) arrives at work and we follow him through the White House while everyone greets him and he interacts until he reaches his desk and sits down with the senior staff. That established the look of the show and what became known as the “walk and talk” style.

THOMAS SCHLAMME: It was actually many shots, and it was done on two different sets that weren’t even connected. The whole thing was worked out and choreographed in rehearsal. It did become the visual signature for the show, even Aaron says that.

Q: How did you arrive at that style?

A: It had to do with the energy I felt in Aaron’s writing, and the idea that everything that was happening in the White House was important. It was a way to express what this institution should feel like—that it never stops. In rehearsal, I discovered that we never had to stop. Rather than do a scene in one room, then stop, and cut to another scene, we could keep it going. It all had to be coordinated between our production designer Jon Hutman, DP Tom Del Ruth, and the sound guys, so that we could shoot every which way, and get through doorways from one room into another room. We used a lot of glass walls that weren’t fixed, they had to be able to be tilted so that if you were getting a kick [light flare] you could adjust it. The thing is, there is so much information in every episode, and when the characters are walking, they’re getting it from all sides. But you’ll notice, in some moments there is some coverage—they’ll come to a stop, or turn—and that’s to let the audience know that here, this is information you need to hold onto. It’s all choreographed to the storytelling. It’s driven by the material, as opposed to, ‘Oh, walk and talk is the style, so that’s what everybody should be doing.’.

Q: Why did you build the White House on two unconnected sets?

A: Because it was way too big. We were a new series, and a pilot at that, so Warner Bros. was never going to give us Stage 23, which is the big film stage. After the first year, we convinced them. We said, ‘It’ll save us time, let us build the largest television set ever.’ But for the pilot, we had to cut and move to a different stage across the street. Then the actors had to pick it up at that exact same pace and energy level so that the action appeared to be continuous.

Q: How did you direct Martin Sheen as the president?

A: Martin is so friendly and warm that what I had to work on with him was getting him to be dangerous. Because at the bottom of it all, it has to be ‘don’t fuck with this guy.’ He’s the president, and he got here for a reason. In the episode ‘Noel’ in season two, there’s a scene where Bradley Whitford screams at him, and that’s a line you just cannot cross with the president. All Martin wanted to do was be compassionate to the character, as opposed to rage, which was what I wanted from him—the idea of, ‘I don’t care what the reason is, this is unacceptable.’ That was very hard for Martin to convey. We wound up just doing it with a look.

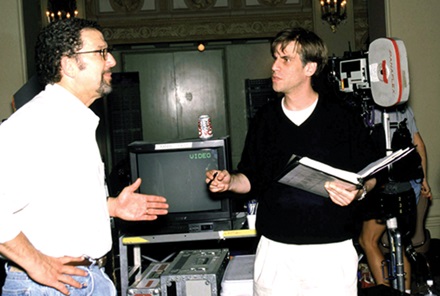

As director-producer, Schlamme forged a close partnership with writer-producer Aaron Sorkin on the show. (Photo: Everett).

As director-producer, Schlamme forged a close partnership with writer-producer Aaron Sorkin on the show. (Photo: Everett). Q: Do you think it would be possible to do a network drama set in the White House today?

A: I honestly don’t know. I think The West Wing hit at a moment in time that was just right for that show. We were just ending a century and going into a new one, and that engendered a certain amount of hope. The truth is, NBC held the show back for a year, because of the Monica Lewinsky scandal. They felt it was way too much to do a show about the White House while we were still in the middle of that. So I probably owe my career as much to Monica Lewinsky as to anyone, because otherwise I would have been just starting Sports Night, and someone else would have gotten The West Wing. As it turned out, Aaron and I built this great trust by doing Sports Night together, and after that, no one else was going to do The West Wing.

Q: Let’s talk about your roots and how you got into this business. Did you have any idea, growing up in Houston, Texas, that you wanted to be a director?

A: It never dawned on me. I didn’t get to watch too much television as a kid—my father was very strict about it. He was in the retail business, and all I knew was that I wasn’t going to stay there and do that. Probably, the way I ended up in this business was because of air-conditioning. I was a big jock in high school; it was Houston, hot and humid, and tough to do two-a-day practices in football. The theater department had the only air-conditioned class. I met someone there, a teacher called Cecil Pickett, who was enormously influential. And from that point on, I started to formulate what I wanted to do.

Q: What did you learn from him that stuck with you?

A: He’d really break stuff down: ‘What’s going on here? What is this play really about? What’s this guy saying?’ He really unlocked something for me. There’s not a day that goes by when I direct that he isn’t in my brain. By the time I got to college [at the University of Texas in Austin], I was going to movies every night, and I began to understand that people did this for a living.

Schlamme, with John Spencer as chief of staff, tailored his fluid shooting style on The West Wing to fit the material. (Photo: Photofest).

Schlamme, with John Spencer as chief of staff, tailored his fluid shooting style on The West Wing to fit the material. (Photo: Photofest). Q: After college you set out for New York to become a filmmaker. Was it a struggle to find your way?

A: Oh, for years and years. The first time, I ran out of money and went back home. I got a job making industrial films in Houston; I was kind of the freak in the back room. When I got back to New York, I drove a cab, and I’d never even driven in New York before. I kept looking for work, knocking on doors. I think I sent out 105 resumes and got one response. I worked as a production assistant on a couple of films and, finally, I got a job at an animation studio as an editor. After that, work begat work. I got into directing music videos and commercials. I eventually got my break shooting a concert film for Bette Midler in 1984. Some of the guys I worked with on that, I’ve continued to work with through the years.

Q: Do you have any personal traits that made you well suited for directing?

A: I’m a voyeur. I say that with no embarrassment. If I could have a superpower, being invisible would be it, no question. I’m fascinated by human behavior; observing people and seeing how much story gets told without a lot of dialogue, and how much our brain fills in. Also, I’m not an introvert, and I think that was a leg up, especially when I was doing episodic. I could go in among strangers and not worry about what they were thinking of me. I’m engaged, I’m interested in other people. I think that’s just as important as knowing how to do the job.

Q: Early in your career you worked with comedians such as Garry Shandling, John Leguizamo, Whoopi Goldberg and Tracey Ullman. What did you learn from them?

A: I learned what it’s like to work with people who have singular visions. That helped me, over the years, to work with writers who felt just as protective of their material. The muscle I had to develop was to get comics to trust me. There’s nothing harder than stand-up comedy. You’re being judged every 30 seconds. If there are no laughs, it’s not a good show. I learned how vulnerable people are and how sensitive one should be to it, so that I could say, ‘I’m actually here as an ally, not as somebody who wants to take this from you and turn it into something else.’ The other thing was recognizing the way they saw the world, the absurdity of it. I love to laugh, but my brain would say, ‘There’s also a lot of drama in there, and there’s a way you can get that across.’ That’s what I was always looking for, and it was easy for me to balance those.

Q: When Sports Night and The West Wing were on the air at the same time, you were nominated for DGA Awards for both comedy and dramatic series in the same year. How unusual was it for a director to be working in both genres at once?

A: It wasn’t really done in television. It was certainly done in features. That’s why Sydney Pollack was someone I admired. He could do Tootsie, but he could also do Absence of Malice. Michael Ritchie was a director that I absolutely loved—the first Bad News Bears was so dark, interesting and funny. And Robert Altman, too.

Q: You’ve mentioned Altman in other interviews. How did his work influence you?

A: It was the balance of very dramatic moments, and a serious subject like the Korean War in M*A*S*H, with a viewpoint that was funny and absurd. I saw the world that way. M*A*S*H struck me as the first American movie that was a commercial hit but felt like a foreign film. It was avant-garde—how it was shot, the way form and sound work in it. I saw that you could be commercial, but also play around with form.

BEDSIDE MANNER: Schlamme brought thehalf-hour comedy tradition of rehearsal to one-hour dramas like ER and PanAm (Photo: Photofest)

Q: In television, there was an established way to shoot half-hour comedy, which was a multi-camera, proscenium style. Can you talk about how and why you departed from that?

A: The truth of it is, since I didn’t watch a lot of television growing up, the sitcom form was not something that was ingrained in me. I’d done It’s Garry Shandling’s Show, which involved breaking down walls and working with a group of comics. So when I got a chance to do Mad About You in its second season, I thought, well, the floor out here is the same level as the one they’re working on, and we have dollies. Why does it have to be proscenium? Why can’t it feel more cinematic? I started to push the cameras in there, and shoot it in a different way, out of the fact that it just seemed no one else had done that. The people at NBC said they loved the way it looked. It wasn’t radical; Sports Night was far more radical. Then I got an episode of Mad About You called “Our Fifteen Minutes,” which involved Paul Reiser’s character, who was a documentary filmmaker, setting up in his house to make a real time doc. And I thought, why don’t we shoot the first act without a cut? We’ll use the camera within a camera—sometimes it’ll be on monitors. The camera guys loved it, everybody was so high on doing it, and it had a great energy, a real visual style that was very different. I noticed everybody in that world was hungry for that. There was an enormous amount of talent sticking around. These were good camera guys, with great eyes, so I thought, let’s exploit all that talent.

Q: How did it work out?

A: It worked on “The Quarantine,” and it worked for a while on The West Wing. But when we realized that we couldn’t shoot that show even in eight days, the luxury of a rehearsal day was just too much. As the executive producer, I would still try to empower the directors to spend at least some part of a day rehearsing. I’d say, ‘Please, it’ll save us money in the long run if you know what the scene is.’ In some ways, what I was doing was pushing half-hour and hour television closer together. So when I was nominated twice in the same year, the shows weren’t that different. I felt The West Wing had some incredibly funny scenes, and of course Sports Night had that. It just happened to be that one was half-hour and one was an hour long.

Q: You landed the pilot of Sports Night after telling Aaron Sorkin that your instinct was to be unconventional with it. What did you say?

A: The way I pitched it to Aaron, and to ABC, was the way we ultimately did it the second year; no laugh track and no live audience. It was really unusual to fight for that at the time. The economics of television were so driven by the half-hour sitcom, which was an enormously profitable format. What I said was, ‘Let me have a fourth wall. I’ll get it done in the same amount of time. You build a set with a lot of doorways that the crew can get through.’ A lot of the sitcom restrictions were conditions of what the camera could read, and how much light you could have, but cameras were becoming much more sensitive. By the time I did Sports Night—even the first year—I could say to Peter Smokler, the DP, ‘Look, I’m shooting every which way here, and I can’t wait for you to do re-lights, so create an environment that works.’ And he was able to do that. For the first season, we did have a laugh track, but it became ridiculous. It was disconnected from the tone of the show. We fought and fought, until it was gone.

Q: It seems like some of the energy and visual trademarks associated with The West Wing were actually established on Sports Night. It looked like a single-camera show, even though it wasn’t.

A: It was a hybrid. I had three cameras in almost every scene. If I was doing a Steadicam shot where the characters stopped in a doorway, I could sneak in two other cameras that came flying in to shoot overs at the same time. That’s how I could get 40 pages shot in two-and-a-half or three days. The idea was, how do I create this energy and adrenaline that makes it feel like a live television studio, where you have to go on the air every night at the same time, no matter what? Visually, I could do it with a Steadicam—a lot of motion, a lot of cuts, and cameras in various places so you could stay with someone while they leave one room and move to another. And the sets had to be connected, so it would feel like a real place.

Q: On those two shows and Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, Sorkin was the writer-creator, and you were the executive producer who directed the pilot and hired other directors. What are your thoughts about that kind of partnership between writer-producers and director-producers?

A: The way Aaron and I worked on The West Wing and Studio 60—that was a real partnership. All he wanted to do was write, and be in the writers’ room. To me, that’s a full-time job. So what’s the best way to utilize the talents around you? With a director-producer, you have a partner on the set, giving the individual episodic directors the attention they deserve, making sure they are available for the actors and helping to deal with the studio and the network. Bottom line—it can make the show better.

Q: What’s the biggest obstacle to the inclusion of more director-producers?

A: The idea that there’s a finite amount of power. The belief being if someone comes in and takes some, you’ve lost some of yours. As opposed to, when someone comes in you actually get freed. With the advent of cable, and with network shows becoming more cinematic, television has become much bigger than just a writers’ medium. The idea of a show-runner in the past was always, ‘I run the whole show.’ But with the size of these shows now, no one person really can. You need a partner, not to diminish your power, but to enhance it, and allow you to do the job you’re being asked to do. For me not to talk about the advantages of director-producers on a show would be criminal, because I so believe in it. A TV show with a good director-producer is going to be far more sensitive to what episodic directors are there to do, and clear about their creative contributions. A lot of times those contributions are infringed upon because people don’t even know what they are. For an episodic director who moves from show to show, it can be difficult to speak up. They need an ally and a strong director-producer can be that person. The Guild has a director-producer program headed by me, Paris Barclay, Rod Holcomb and Michael Zinberg. We have seminars where people who do this job can hear from each other, and educate those in our membership who are ready to step into that position.

Q: Most of the directing on The West Wing was done by you, Alex Graves and Chris Misiano. Can you talk about how as a director-producer you worked with other directors?

A: I did something other shows hadn’t done, which was hiring two directors to be producers. On most shows, you have a staff of writers who all get producing credits; this is done so they get paid for a whole season and not just the scripts they are credited for as writers. I thought since Aaron is writing all the episodes let’s have a smaller staff and put two directors on and give them a producing credit. Not only were all three of us actually able to help produce the show, it also gave us more directorial consistency which meant Alex, Chris and I directed 80 percent of the shows. However, as a vice president of the DGA, I was concerned: Does this mean that other directors aren’t getting an opportunity? But if you do the math, you’re taking these three directors out of the talent pool, who would otherwise have gone on to do six other shows that they’re now not available for. It balances out.

Q: How else has the Guild addressed issues episodic directors face—things like late scripts and long scripts.

A: The late script issue has been worked on. The Guild has been diligent, and has affected the culture in changing that. But long scripts is something that is just now being looked at. It’s really difficult—no one’s willing to make the harder cuts earlier, so the show isn’t butchered up later. And the episodic director makes a living by being invited back, so it’s hard to walk in and say, ‘I just can’t do this in eight days.’ What you need is someone there, a director-producer who already has a strong relationship with the writer-producer, who can help that writer understand that from a creative point of view there is too much story to fit in the allotted time and better to make the cuts before shooting than after. At the same time, episodic directors have to remember that by the time they have come in, the writer may have been “noted to death” by the studio and network on that particular episode. So be sensitive to what they are also going through.

Schlamme, working with Nathan Corddy on Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, tries to keep it fun and involve the actors in the process. (Photo: Everett)

Schlamme, working with Nathan Corddy on Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, tries to keep it fun and involve the actors in the process. (Photo: Everett) Q: As an executive producer on the Sorkin shows and series such as Pan Am, Parenthood and Mr. Sunshine, what do you look for when you’re hiring episodic directors?

A: The last thing I want to do is micro-manage. I have enough to do. I want talented directors to come in, take ownership of the show, and run with it. You look at people’s work; you talk to other people who’ve worked with them. You’re looking for a distinct voice, who also has the ability to apply that to the show’s particular parameters. On The West Wing, I had set up a way to shoot the show, but if you didn’t want to use the Steadicam, if you’d figured out another way to keep the energy going, then by all means go for it. I never sat with any director first and talked about how they were visually going to shoot the show. What I cared about was, did they understand what this particular episode was about? Have you figured out what the story is here, and how you’re going to tell it? That’s where I’d work with people the most.

Q: When you’re prepping to direct a script, whether it’s a pilot or an episode, what is your thought process for figuring out the story you’re telling?

A: I’ll read it over and over until every beat of it is clear in my head. Then I’ll set it down and write an outline, to break down the story I want to tell. If I forget a scene, maybe it wasn’t important, maybe I was able to connect the dots without it. Regardless of the genre, you’ve got to personalize a script—you’ve got to find something in it you connect to, a story you really want to tell. If it’s a pilot, and I’m lucky enough to get to work with the writer to develop it, I’ll say, ‘what story do you think you’ve written?’ Then I’ll try to help, the best I can, to open it up to possibly more visual storytelling.

Q: You’ve done seven pilots in a row using the same editor, Rob Seidenglanz. Can you talk about how you work together.

A: When I do a pilot, I stay with it all through postproduction, the way a movie director would. The interesting thing about the way I work with Rob is that I give him the script and ask him what he thinks it’s about, because I really want to know. And then I’ll tell him why I’m doing it—what I see as the real story, emotionally. I talk to him the way I’d talk to a writer or actor. Very seldom is it the nitty-gritty of , ‘Can you start with a wide and go to a close-up.’ Instead, it’s, ‘What does the character want in this scene?’ If I have storyboards, I won’t share them with the editor, because I really want to see what he comes up with. I’m always amazed that there are so many more ways to cut a scene then what I had in my head.

Q: What about your directing team, what kind of relationship do you seek to establish with a 1st AD.

A: YI had an incredible experience with Amy Sayres on So I Married An Axe Murderer, which was a very difficult feature. She was an amazing ally, and a real partner in filmmaking. She understood how to manage and schedule an army as well as how to handle the creative end. Phil Patterson, an extraordinary 1st AD who works with Terry Gilliam, just did a pilot with me called Frontier that we shot in Australia. I rely very heavily on that relationship. ADs are in the trenches with me as much as anyone else, all the way through the process. From the very beginning of prep, they understand what has to be accomplished. In every relationship I’ve had with a 1st AD, they’ve been more persevering in making sure I get everything I want than I am myself. They so want the film to be the film we’re all thinking of. Something else that’s undervalued in the world of television is how powerful and instrumental the 1st ADs are to the episodic directors. It’s one more advantage of having a director-producer on a show, because then the 1st ADs can feel really empowered to be supportive of the episodic director coming in.

Q: We’re in the midst of the election season now. In 2000, the presidential election took place just a couple of months into season two of The West Wing. Did you acknowledge the changing of the guard on the show?

A: Together with NBC we had prepared two crawls that were going to run with the credits: The cast and crew of The West Wing want to wish the best for President-elect Al Gore, or George Bush—regardless of who it was. Then Wednesday came, and we couldn’t run either crawl. What happened in that election was the last story line we could have ever come up with.

Schlamme has continued to develop shows with political content, including Jack & Bobby, about two brothers, one of whom grows up to be president. (Photo: Mitchell Haddad)

Schlamme has continued to develop shows with political content, including Jack & Bobby, about two brothers, one of whom grows up to be president. (Photo: Mitchell Haddad) Q: What kind of cooperation did you get in Washington when you were making the show?

A: When we were doing the pilot, access was hard. They said, “It’s another show about politics, and that’s never been done well.” When the show became a hit, it evolved to the point where in the second season, the Clinton administration actually let us shoot a scene at the White House. It’s in ‘Noel,’ when Bradley Whitford goes out and Janel Moloney walks with him, and they’re playing “The Bells of Christmas.” They let us do it inside the actual gates, at 2 o’ clock in the morning. By the fourth season, we were well into the Bush administration, and Martin Sheen had been actively campaigning for Gore. So yes, it became harder to get access. But it was also post-9/11, and for security reasons, access to any building became harder. When we shot the pilot, traffic was still allowed on Pennsylvania Avenue. It certainly isn’t anymore.

Q: You got some firsthand exposure to the way Washington works while directing and producing The West Wing. Did that diminish or enhance your regard for the American political system?

A: It enhanced it. Part of that comes from a deep respect for the people who commit themselves to doing that job. We tend to demonize people in politics, the same way they demonize Hollywood. There were people I met in Washington whose politics I abhorred, but when I spent time with them, I was fascinated. How did you come up with those views? I’m not talking about people in the media who have to stay with a certain political agenda because that’s how they get an audience. I’m talking about people who literally work in Washington on the Hill. If I was doing The West Wing now, I’d be even more sensitive to trying to understand why, for example, Tea Party people are Tea Party people, rather than just, ‘They’re idiots and we’re right.’ Otherwise it’s just pouring gasoline on the fire and then the opposing army gets stronger. If you’re not trying to understand and say ‘How do I reach across this?’ then what story are you really telling?