By DAVID KRONKE

Director Mark Cendrowski

Director Mark Cendrowski The walls of Mark Cendrowski’s office in The Big Bang Theory’s Warner Bros. soundstage are adorned with framed photos of the director with cast members and guest stars. Conventional enough, except in these photos, everyone—from Bob Newhart to a Muppet—is contemptuously rolling their eyes while Cendrowski is attempting to give them notes. The joke’s on him, even if he’s staged it himself. “Like I’m the stupidest director ever,” Cendrowski says with a laugh.

Clearly, Cendrowski-as-boob is just a whimsical fiction he enjoyed creating, perhaps his attempt to ally himself with the show’s characters, a group of nerdy, socially awkward Caltech physicists who are dumb about things ordinary people tend to be smart about. Cendrowski has directed 118 episodes of The Big Bang Theory, which begins its seventh season in September. In the course of its run, it has been nominated for two Outstanding Comedy Series Emmys and Cendrowski himself was nominated for a DGA Award in 2012.

During a visit to the set for the season six finale, it’s obvious Cendrowski has secured the respect of his cast and crew. Many of them—from series star Johnny Galecki to the soundstage security guard—offer unsolicited glowing testimonials. Series co-creator Chuck Lorre says, “Mark has evolved into the ideal four-camera director. He creates an easy-going vibe on the stage that helps everyone focus on the task at hand without being overwhelmed by performance jitters.”

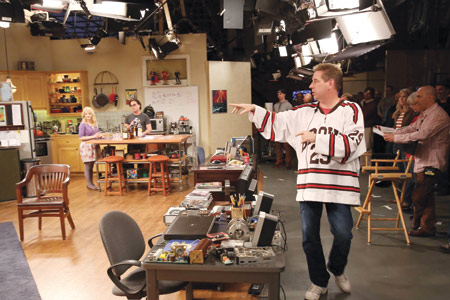

And when it comes to shooting, adds Lorre, “He keeps the pace up so the studio audience doesn’t lose focus. His camerawork is just about flawless. He has a great sense of comic timing and nuance. Frankly, aside from his penchant for wearing hockey jerseys, he’s a damn near perfect director for The Big Bang Theory.”

On this day, however, Cendrowski is dapper in a black fitted shirt and herringbone tie. Dressing up on taping day is a tradition for him that goes back to his days as a stage manager on Full House and Roseanne when the director was up in the booth and the one representative of the directorial team on the floor. “We tried to make it nice [for the audience] that we were doing a show—it was a performance. I wore ties on tape night, tried to make it special for them.”

GOAL ORIENTED: Mark Cendrowski, in his customary hockey jersey, has directed 118 episodes of The Big Bang Theory and learned to create an easy-going atmosphere on the set.

GOAL ORIENTED: Mark Cendrowski, in his customary hockey jersey, has directed 118 episodes of The Big Bang Theory and learned to create an easy-going atmosphere on the set. Cendrowski is leading the cast and crew through their final run-through before presenting the episode to network and studio executives. Chatting with an interviewer on breaks, even later during the evening’s taping, doesn’t seem to faze him or break his concentration. After monitoring one scene, he matter-of-factly goes about his business: he suggests cast member Kaley Cuoco tweak a line reading to emphasize a sweetly sardonic attitude, and that a camera operator take a tighter shot to highlight her line. He seems to possess a preternatural ability to keep lots of plates spinning at once.

“That’s part of the key for directing—the people who can do it all have to be aware of everything that’s happening onstage,” he notes. “You may not be able to fix it all, but you know if there’s a problem. Even while training as a stage manager, I was on the floor when the director was in the booth and was able to see what was happening. It helped sharpen my eye for detail.”

“He’s seeing everything,” agrees his 1st AD, Anthony Rich, who has taken the reins of a few Big Bang episodes himself. “He’s phenomenal at preparation and brings that great energy. When you treat people with respect, they want to give you everything.”

Another secret to successful directing, Cendrowski and Rich agree, is deceptively simple: run the show like summer camp and keep everyone happy and busy. “The way I like to run a stage is to keep it loose and fun,” Cendrowski says. “Everyone does their work, but the more fun you can have puts everyone in the right frame of mind to make a comedy. I’ve worked on a lot of shows and worked with a lot of directors, good and bad, and I never liked working on a show where everyone was walking on eggshells. You can have fun; you can make mistakes and put yourself out there. That’s where comedy comes from.”

Adds Rich, “You want a stage that’s an upbeat place for the actors so they feel free to try what they want to. The playfulness is all by design. Because when someone comes in and they’re slightly off, the entire day can go down fast. Or if you’re working with someone toxic, you have to keep that energy away from the cast and the crew.”

To that end, Cendrowski has cooked up all manner of extracurricular activities to keep his team engaged. He even interrupted a taping to stage a choreographed flash-mob dance number led by the cast, during which the crew and other dancers flooded in from the sidelines—a spectacle that initially bewildered and ultimately delighted the studio audience.

Four-camera directing requires the director to cut the show while taping. Because the live studio audience is often watching the action on monitors, an initial sloppy video feed can dilute their response.

“Knowing editing is very important,” says Cendrowski. “What we show the audience [on monitors] is like what they’ll see at home. I’m not just shooting a bunch of coverage and saying, ‘Oh, the editor will fix that eventually.’ I know this joke will work better if it’s shot in a single, and then we cut to a reaction. That’s what we try to do for the audience.”

At today’s run-through, Cendrowski is fine-tuning. “I’m looking at the shots saying, ‘That’s too wide, let’s lose his reaction; or, let’s make sure we get a single; and, let’s punch his face and we’ll get a bigger laugh.’ Sometimes I can blow a joke because of the way it was covered. We’re doing the show for the 250 people here—they dictate everything.”

Cendrowski believes a director’s stylistic intentions should never override the comedy’s substance. “The visual style for comedy is to stay out of the way of the comedy, to make sure the audience is seeing it,” he says. “I remember seeing an episode of The Dick Van Dyke Show with three people sitting at a table—it went on for a minute and a half without a cut. Nowadays, that’s unheard of. It would be a three-shot, reaction, two-shot, single, tighten it, pull this up. What was funny was the story line; not the reactions, but what the person was saying. And the way to cover that was in the three-shot.

“You can get in the way of the comedy with your cameras if you try to get too stylistic with sweeping moves,” he continues. “You can counteract the comedy, particularly with this show, which is tight and fast-paced. The rhythm of how it’s written and how we cut it is very tight.”

VARIETY SHOWS: (top) His kids were finally impressed when he started doing shows like Wizards of Waverly Place. (bottom) Cendrowski was impressed with the physical comedy of Jim Belushi on According to Jim.

Which doesn’t mean there isn’t room to be inventive. Cendrowski’s DGA Award nomination came for “The Date Night Variable,” an episode in which scenes were set aboard the International Space Station.

Creating the station’s zero-gravity environment was “an absolute blast to do,” Cendrowski says with a wide smile. “We did it onstage, and I’ve never had so many people ask me, ‘How did you do that?’ Some people thought we went up in the Vomit Comet [a zero-gravity aircraft], but we built the set knowing it would be used for four weeks. We had the cameras on a gyroscope and we didn’t use wires at all. All the actors you see floating were on teeter-totters or pushed in on a giant metal arm.”

Back on the ground, it’s now midafternoon and the notes session with network and studio executives is basically a pro forma affair, except for one scene in which blocking had separated two characters who had to react to one another for comedic payoff. Cendrowski quickly figures out another camera angle that places them in the same frame to achieve the laugh.

“I had blocked a scene one way and an EP made the suggestion, ‘Could they be together for that?’ Instead of saying, ‘No, they could never do that!’ I was listening and thinking and wondering, ‘How can I can accomplish that?’ It’s listening to their vision of how a joke should be and figuring out how to make that work.”

Gay Linvill, Cendrowski’s associate director and a veteran of multi-camera shows such as Days of our Lives, says, “His skill set is almost unrivaled, and I’ve worked with a lot of people. Nobody can fix cameras as fast as Mark. He’s so facile; he really gets it. Multi-camera is the most collaborative art there is and he knows how to run the team—he’s the captain. Tonight, they’ll rewrite the script or rework a joke where our coverage won’t work as well. And he’ll call an audible: ‘Get a two-shot over here, C camera, you go in for a single’—and he’ll nail it.” fter the executive run-through, Cendrowski heads back to his office where he reflects on his career, which began with a brief foray into stand-up comedy. He has directed episodes of more than 50 multi-camera comedies; prior to The Big Bang Theory his biggest success was on the hits According to Jim (24 episodes) and Yes, Dear (35 episodes).

Of According to Jim, he says, “I was really proud of the physical comedy we were able to pull off. Jim Belushi and Larry Joe Campbell were both very light on their feet and willing to do anything. So even if the situation didn’t call for it, there was a chance we would explore something slapstick. I remember one of the first weeks I was there, Larry Joe practiced jumping into a garbage can even though we didn’t think it would stay in the script.”

Yes, Dear presented a different challenge: directing the distinctively different acting styles of its two stars, Mike O’Malley and stand-up comic Anthony Clark. “Mike O’Malley had the acting and comedic chops and Anthony Clark could get you the funny,” he recalls, “so you had the actor who was willing to work to find the performance with the comic who was intrinsically funny but didn’t really come alive until the audience was there. Getting them to work together was the challenge.”

Cendrowski has also directed comedies for the Disney Channel, partially because he wanted to do work his children could watch; the fact that they shot during the summer, when network sitcoms were on hiatus, was also a bonus. Initially asked to work on the quirky Wizards of Waverly Place, he eventually added assignments on Hannah Montana, The Suite Life on Deck and Cory in the House.

“When I tell my kids that I’ve worked with Alfred Molina and Betty White [stars of the short-lived Ladies Man], they’re like, ‘Big whoop,’” he says, laughing. “But when I say I worked with the Jonas Brothers [on Hannah Montana], I finally got some respect. They said, ‘Oh yeah, you’re cool.’”

What Cendrowski himself finds cool, however, is the fact that he has worked with such personal comedy heroes as White and Bob Newhart and an international icon like Stephen Hawking. Directing White on Ladies Man was the first time Cendrowski was starstruck with one of his cast members. “I couldn’t look her in the eye the first time I gave her a note,” he admits. “But she knew exactly what a director needed, and she delivered.”

Newhart appeared on The Big Bang Theory this past season. “Hearing that he was coming in was like Christmas morning to me,” says Cendrowski. “He’s one of my favorite comedians and to have a chance to work with him and talk to him about jokes didn’t seem real. Bob appreciated that I could block things in a way that would maximize his humor.”

But landing the British theoretical physicist Hawking for an episode was simply “surreal,” Cendrowski says, “like getting Albert Einstein to do a stand-up joke. It was like the biggest thing in the world, like the Queen was here.” At a run-through a cast member did an imitation of Hawking’s computer-generated voice (apologizing profusely beforehand). “There was a buzzing around Hawking’s wheelchair and we thought he was having a stroke,” Cendrowski recalls, “but no, that was how he laughed.”

So what kind of notes does a director give to someone like Stephen Hawking? Cendrowski pauses momentarily to think about it. “Be smarter?”

In fact, there are a couple of Stephen Hawking jokes in the episode shooting tonight. (As part of his make-it-special-for-the-audience practice, Cendrowski is wearing a herringbone jacket over his shirt and tie.) The first Hawking joke gets one of the biggest laughs of the night; the second, not so much.

“There was a joke and a follow-up—we rehearsed it that way all week, and it was working well,” Cendrowski explains. “You get into a rhythm, then the first laugh was so big that it threw the timing off for the second joke, so it didn’t land nearly as big. That can throw an actor, getting a response you’re not expecting. So I have to get them back on track, or change the rhythm of the scene.”

Unexpected laughs can also lead to camera adjustments. “We’ve heard the timing of the laugh, so my cameraman knows how much time he has to swing to another reaction to steal it during a sustained laugh. My job on the fly is to come up with that. It’s a good problem to have.”

In the end, the second Hawking joke is jettisoned. Between setups, when he probably has a half-dozen other more pressing things he could be doing, the ever-composed Cendrowski takes a moment to explain why the joke was cut. “The first Hawking joke was so big, the second one couldn’t possibly beat it. We probably shouldn’t have even tried. But that’s why you do it in front of an audience—they let you know what works the best.”