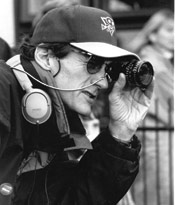

By ROBERT ABELE

When John Badham scouted discos all over New York during preproduction for Saturday Night Fever, he realized nothing captured the vibe of a slightly worn, inexpensive hangout better than the 2001 Odyssey nightclub in Bay Ridge, which was featured in the original New York magazine article that inspired the movie. Since he was telling the story of a Brooklyn striver and amateur disco king named Tony Manero (John Travolta, in a career-making performance), it made sense to stay real and stay local. “After seeing all these places,” recalls Badham, “we said, ‘This is about the neighborhood.’”

When John Badham scouted discos all over New York during preproduction for Saturday Night Fever, he realized nothing captured the vibe of a slightly worn, inexpensive hangout better than the 2001 Odyssey nightclub in Bay Ridge, which was featured in the original New York magazine article that inspired the movie. Since he was telling the story of a Brooklyn striver and amateur disco king named Tony Manero (John Travolta, in a career-making performance), it made sense to stay real and stay local. “After seeing all these places,” recalls Badham, “we said, ‘This is about the neighborhood.’”

The 1977 film became a disco-era touchstone across the country, transformed the Bee Gees into music superstars, and turned the white suit Travolta wore in the final dance contest into an iconic fashion statement. Faddish significance aside, however, the competition is a carefully directed emotional climax, from its lilting romantic dazzle to the moment when winning top prize over better dancers flicks on the biggest light in that glittery arena for Manero: the realization that he’s only a big fish in a small pond unless he gets out.”

Badham explains the directorial moves that led to a justifiably classic sequence, one that shifts from the dreams of small-timers to the choreographed ecstasy of a romantic dance, until a dose of reality shuts off the music for our hero. “This is not just a dance,” reminds Badham. “It’s the major turning point of the film.”

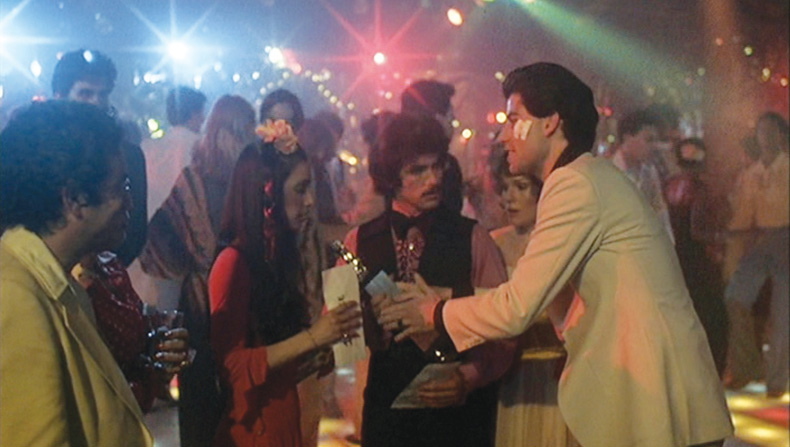

Stephanie (Karen Lynn Gorney) is waiting in the cold, concerned about the contest, wondering if Tony is going to show up. That sign that looks like it was done by hand? I remember being on our sign writer’s case, ‘It cannot look like it was professionally done. It’s got to look like Mr. Amateur trying to save a few bucks, like the raw feeling of the neighborhood.’ Then, when you get inside, we’ve created this magical fantasy; one with cracks showing, but just enough of a fantasy.

The prizes had to look exactly like what you’d walk in and buy off the shelf for whatever you could afford, so these came from the local trophy shop. The truth is so much more fun than fantasy. Even our wardrobe was all off the racks. We didn’t make a single thing, except maybe the white dress that she wears. My approach to the film was, we’re documentarians coming from Asia to shoot what’s going on, what we see.

We have no idea who the other couples [in the contest] are as human beings. It’s bam! They’re on the stage. But these are people we’ve been following; we care about what they have invested. So the difference from the explosive entrance of the other two couples is that we’re going into a legato mood with the music, and sliding into it. This shot helps keep track of things like what space they’re in: Do they have butterflies? Is it going to be good? All that stuff. You want to be able to read that on their faces.

We’re on a Stage Crane, a clumsy thing, but it worked. It was hard to fit into the 2001 club, because the crane only went up to about 12 feet. You have to get the operator, focus puller, and camera all mounted on a platform that’s heavily counterweighted. This is a very gentle move, to give you the geography of the place and the mood without being static. As for playback of the music, the important thing was that it be identical with the final track. It’s not a good idea to just have a rhythm track. I told the Bee Gees, ‘Guys, give me your latest demos for playbacks, but please promise you won’t change the tempo.’

We’re on a Stage Crane, a clumsy thing, but it worked. It was hard to fit into the 2001 club, because the crane only went up to about 12 feet. You have to get the operator, focus puller, and camera all mounted on a platform that’s heavily counterweighted. This is a very gentle move, to give you the geography of the place and the mood without being static. As for playback of the music, the important thing was that it be identical with the final track. It’s not a good idea to just have a rhythm track. I told the Bee Gees, ‘Guys, give me your latest demos for playbacks, but please promise you won’t change the tempo.’

This is to break things up, to avoid being on eye level—but only when it made sense. Not just going to wacky places because it’s wacky. Here you’ve got this couple marching forward together, and it just looked really powerful low. They’re strong looking and that angle gives them strength. We’re trying to support the feeling, ‘This is cool, we’re out here strutting.’ In a way, it’s an echo of the opening of the film, when Travolta is walking down the street with these up-angles on him in his absolute street arrogance, as if he owns this world. It’s an extremely wide lens. They’re virtually bumping into the camera at that point.

The biggest thing we did for the 2001 was put in that floor. It was based on a nightclub in Birmingham, Alabama, where I grew up. Production designer Charles Bailey designed it, and a place in New York made the modules. We told them what colors we wanted, and Ralf [Bode, the DP] said, ‘Don’t get me too much green, it’s going to make their faces look green.’ Simple electronics made the lights go to the beat of the music, but it was better to do it manually, so we could be exactly in sync with what the dancers were doing. We trained a young woman to do that, and she was really good. So here we’re going with as much romanticism as we could.

It was nice to be able to include the disco ball. Part of our whole concept was that seeing the lights was never a problem. We didn’t have to avoid them, we were in a disco! There were lights there! It was designed so you could go 360 degrees around, and there would always be something interesting happening with the lighting. We decorated the walls with aluminum foil, the widest that Charles could find. He just let it hang loose, not stretched tight, so it reflected light all over the place. Then he went out and got cheap Christmas tree lights and strung them all over the place, so if you look in the background, these twinkly lights liven it up..

One thing we did not factor was that people get tired when they dance a lot. We had two suits, and John, like anybody working hard, sweat a lot. We’d have to peel it off him, dry him off, put the fresh one on him, and then take the wet one outside with a hair dryer. The suits were getting funkier and funkier. John originally wanted a black suit. I said, ‘I think white would be nice.’ John said, ‘Black is really cool.’ So I said, ‘Well, Karen will really like that because she’s in a white dress, and the black will disappear in the lights. All we’ll be looking at is her.’ At that point, the bell went off. So John and our costume designer Patrizia von Brandenstein went out and came back with two white suits.

I wanted to shoot this picture in 1:66, because dance is a vertical medium. 1:85 is not the most friendly for dance, but it was the best I could get. With dance, and certainly with action, you can compose shots to the way the figures go because they’re in motion—it makes for beautiful composition. So in tilting her back, we kind of tilt with them, or ‘Dutch’ the camera, which is the phrase they use in this particular aspect ratio. When the characters in the frame do something that justifies that movement, you can frame with them and it’s not weird. The traditional way is to move further back; otherwise, if you keep the camera level, you lose part of them as they tilt over.

They hold that kiss way longer than necessary, and we froze that moment in time. The lighting gets softer, from multicolored to a very romantic blue. The music starts to echo, and we made a gentle transition from 24 frames to 48 frames per second, a critical rate because it still keeps the music on the beat, it just goes into half time. We needed a bit more light because we’re exposing more frames. The guys on the light board brought up the blue, taking down the other lights. It’s using light changes, like you would in theater, to go with the mood. I always had the feeling we were going underwater with them—very dreamy, very liquid. We brought in dry ice, for light smoke to thicken the atmosphere.

Now we ease a little quicker out of the 48 frames, back to the 24. It’s not a radical thing, you shouldn’t even be aware of it. It should be subliminal: you’re suddenly taken into this dream world, not knowing you’re being taken until you’re there, and then eased out. One of the critical concepts for the choreographer, Lester Wilson, was that I never wanted it to feel like these people went to dance class. She’s good, and you can tell she’s working hard, but you can tell he’s better than she is, and at the time she’s the best partner he can get. So this is a very nice dance-off. With actors like these, I didn’t need to spend time saying, ‘You feel this way, do this.’ They just take you places.

You look at what the dancers are doing, and ask, how can we support this, make it better, give them the best chance? Because we were always pressed for time on this picture, I shot this Puerto Rican couple in an hour and a half. I put a camera down low at the head of the floor, one above, then we go handheld to follow her, now follow him, thank you very much, we love you, goodbye. I virtually threw them away. Here, you’ve got this tremendous sense of perspective with them using the floor the way they were. Look at West Side Story: In the numbers choreographed and shot by Jerome Robbins, like the ‘Cool’ number, that camera is down on the floor—it’s a very powerful dynamic.

John understood this character better than I ever would. He needed so little, just support and to know he was on the right track. I never talk to actors about what they’re feeling. It leads to very generic versions of ‘I’m shocked! I’m upset!’ Instead we talk about, ‘What are you doing at this moment?’ He’s discovering that people who you thought were schmucks are better dancers than you, and you’ve lost the contest. We’re lighting him the way lights would be hitting him in the disco, from different directions. There’s a nice low backlight, and a soft light bouncing off the floor.

For this we were using the very earliest version of the Steadicam, called Panaglide. It was a crowded floor, and I wanted to be on their faces the whole time as they wind up in this wide two shot. If I were shooting a TV episode, they would have cut my balls off because I should have had coverage of the Puerto Rican couple saying ‘Thank you!’ But I made it one shot because you get all of his mood, his anger. He’s walking the length of the floor, dragging her behind him. You see the transfer of prizes, them walking away, and now the shock of the Puerto Rican couple. When you stay in one shot, you get caught up in the reality more than the artifice of cutting.

For this we were using the very earliest version of the Steadicam, called Panaglide. It was a crowded floor, and I wanted to be on their faces the whole time as they wind up in this wide two shot. If I were shooting a TV episode, they would have cut my balls off because I should have had coverage of the Puerto Rican couple saying ‘Thank you!’ But I made it one shot because you get all of his mood, his anger. He’s walking the length of the floor, dragging her behind him. You see the transfer of prizes, them walking away, and now the shock of the Puerto Rican couple. When you stay in one shot, you get caught up in the reality more than the artifice of cutting.