By Ann Farmer

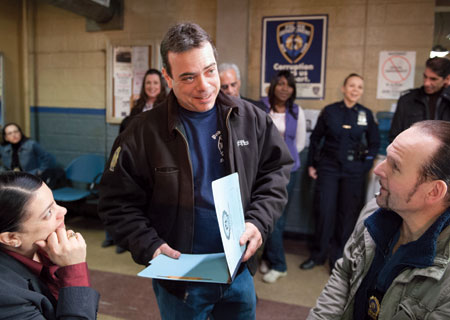

Aspromonti, working on the precinct set in Brooklyn, creates a story to help background performers.

Aspromonti, working on the precinct set in Brooklyn, creates a story to help background performers.

On unseasonably warm February day in New York, Blue Bloods guest director Christine Moore is leading actor Donnie Wahlberg through take after take on the cop show’s squad room set. Each time, Wahlberg’s hard-nosed detective dominates the frame, chewing out a colleague for insubordination.

But at the same, police life is going on behind Wahlberg, giving the scene an authentic lived-in quality. A background actor pretends to be making photocopies on the precinct’s Xerox machine. Her understated presence in the picture is something that Joe Aspromonti, the 2nd 2nd assistant director, set up.

“I showed her the frame,” says Aspromonti, motioning to a small monitor in a corner of the set where the cameraman is shooting. “I told her to fill it up. Not too many specifics. Just be a detective.

“See the officer over there,” he continues, in a hushed, gravely voice, pointing to a background actor wearing a police uniform. “He’s going to take a perp to a jail cell. When he passes him off to another officer, that’s the cue for these two other extras to come out of the radio room to discuss a case and pass around some paperwork. Instead of [having them] walking around aimlessly,” explains Aspromonti, “I give them a little story.”

On Blue Bloods, there are many stories—big and small—going on at once. The series is characterized by its often large contingent of background performers, impressive stunt work, and a shot-in-New-York look achieved by squeezing multiple locations within a rigorous production schedule. It’s a challenging show for everyone and the job of the directorial team is to make it easier for directors to focus on the primary actors and main narrative so they can realize the episode’s goals.

PASTRAMI ON RYE: 1st AD Jono Oliver (3rd from left) prepares a scene on location

PASTRAMI ON RYE: 1st AD Jono Oliver (3rd from left) prepares a scene on location

at Katz’s Deli, aided by 2nd 2nd AD Joe Aspromonti (arms crossed).

“We pride ourselves on being very organized and prepared,” says co-executive producer Michael Pressman, who was brought onboard after directing two episodes of the show’s first season. He now hires Blue Bloods’ guest directors and ensures that the look of the show remains consistent.

“The AD is there to help the director’s vision. I think our ADs enhance what the director wants,” says Pressman, referring to the show’s six assistant directors, who, combined with unit production manager Kati Johnston and location manager Collin Smith, form Blue Bloods’ hard-driving directorial team.

One way Pressman keeps the episodes cranking is by rotating two AD units: While one unit, comprised of a key 1st and key 2nd, preps for seven days, the other team is shooting (it gets eight days), and vice versa. Aspromonti acts as a swing person, sticking with whichever team is filming. So does an additional 2nd AD, Regina Heckman, who mainly attends to the actors.

“I’m here because of the huge ensemble cast,” says Heckman. “It’s such a big show. There are so many different needs and different personalities,” referring, for instance, to actor Tom Selleck, who plays the head of this multi-generational clan of New York cops. He and the other actors, including Will Estes and Bridget Moynahan, attract fans who turn up on locations pressing for autographs or glimpses. Dealing with the fans in a friendly but firm manner falls to Heckman.

The ADs know exactly what is expected of them. And on this particular day, it’s 1st AD Rebecca Strickland running the precinct set, one of three stages that comprise Blue Bloods’ production base, located in a former warehouse in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, a Polish working-class neighborhood now partly overrun with production studios.

Strickland arrived early enough to determine that all the elements—including cast, crew, and props—were all accounted for. The director subsequently rehearsed with stand-ins and ordered the set marked and lit. Then it’s time to shoot.

“Ladies and gentlemen, quiet, please,” Strickland announces, the first of many times during the next 10 or so hours that she will utter those words. It’s her role to maintain order for the guest director, and Strickland, who often jokes with the cast and crew between takes, is able to manage the set in a voice that sounds authoritative but not bossy. Whenever she’s called away from the set, Aspromonti or 2nd AD Marc Garland steps in to pick up the slack.

Moore, who is in the midst of directing her first episode of Blue Bloods, asks for the cast to be brought in. Then she tells Strickland to call the roll. Strickland again asks everyone to pipe down. Continuing, she says, “OK, cameras, you guys good?” Receiving an affirmative response from the camera operators, she orders, “Roll sound, background.”

POLICE WORK: 1st AD Rebecca Strickland arrives early to pull the pieces together

POLICE WORK: 1st AD Rebecca Strickland arrives early to pull the pieces together

and gives 2nd AD Marc Garland information about cast, crew and prop changes.

Strickland, Moore, and Aspromonti cluster around the two set of monitors to scrutinize the take. If Moore or Strickland sees something going on in the background they feel isn’t working, they will alert Aspromonti. This time, however, it’s Aspromonti who is dissatisfied with the timing of two extras walking through the scene as plain-clothes detectives. “If you move in a little quicker,” he tells them, “you’ll nail it.”

In some instances, Strickland might alert the director if she notices something out-of-the-ordinary that would compromise the style of the show. “If we’re shooting a scene in the squad room and the director wants it super busy,” says Strickland, “my job is to say, ‘The tenor of this show is not usually busy, busy.’ Or I might say, ‘We’ve never had it this busy.’ ”

She is also responsible for the shoot to happen in a timely fashion. “I need to let the director know if it’s going a little long or if we’re ahead,” says Strickland, who walks around with a walkie-talkie often glued to her mouth. It connects her to over a hundred people in all production departments.

One of them is UPM Johnston, who periodically calls Strickland for an update. “As I’m coming and going from the set,” explains Johnston, “I rely on them to tell me how things are going, to take the temperature of the day. If the crew is fatigued and needs a break, I rely on them to feel that out.”

More often than not, though, it’s 2nd AD Garland on the other end of the walkie-talkie. Garland is responsible for dealing with scheduling changes and disseminating any information that Strickland needs to get out. “Because I’m spending time with the director, DP, and producer,” says Strickland, “I can’t be prepping and telling everybody, ‘Hey, I added a bus to this scene.’ The 2nd AD does that.”

All morning, Garland has been upstairs calling departments to alert them to some script changes related to Monday’s shoot (two working days away). Garland says the departments usually pick up on the script changes themselves. “But I like to follow up,” he says, especially since script changes usually mean that other elements need to be added, amended, or eliminated.

In this instance, there’s been a shift in the script’s family dinner scene. Each episode of Blue Bloods ends with the entire clan having a meal together. This episode was originally written with the family cleaning up at the end of the meal. But now the family is just sitting down to eat, “which means that the prop department is going to have to put together that food,” says Garland. “I’m making sure everyone has all the information they need.”

LONG DAY: (above) 2nd AD Daniela Barbosa is first to arrive on the set and sometimes the last to leave;

LONG DAY: (above) 2nd AD Daniela Barbosa is first to arrive on the set and sometimes the last to leave;

(below) After directing two episodes in the show’s first season, Michael Pressman (right)

came on board as co-executive producer.

Garland has a knack for organizing. He began his career as the artfully named “director of covert activities,” setting up the props and magic for the magician duo Penn & Teller. When they filmed Penn & Teller Get Killed, he got a taste of what ADs do. “I liked the jigsaw puzzle of it,” he says, and began refashioning his career as an AD on TV shows such as Sex and the City and Cashmere Mafia.

Garland’s counterpart on the other AD team is Daniela Barbosa, who segued into AD work after pursuing a career as a child actor on Sesame Street and in movies. She says she’s happy to be working behind the scenes now.

“Being an AD means being responsible for everything. You take care of the crew and cast. You know everything that’s going to occur,” says Barbosa, taking a rare moment to sit down. Then she and Garland begin describing all the challenging paperwork they generate as 2nd ADs. Creating call sheets, for instance, isn’t just about filling in the blanks. First they talk to each department about how much time is needed to accomplish tasks. “I don’t say to people, ‘You have this much time,’ but, ‘Does this work for you?’” says Garland.

Every minute of the day is accounted for. When planning yesterday’s hair and makeup call time, Barbosa scheduled it for 5:12 a.m. (not 5:10 or 5:15). “We go through the whole thing,” says Barbosa, “extras, props, dates, locations, how people get to work, the temperature, all the things you’d think, ‘Oh, we’re adults’ and aren’t necessary,” she laughs.

“And ultimately, things rarely work out as planned,” adds Garland.

Later in the day, for instance, Barbosa discovers a glitch in tomorrow’s call sheet regarding a pre-dawn cast and crew van pickup at a Manhattan subway station. The stop, it turns out, is going to be shut down for overnight repairs, making it difficult for some actors and crew to arrive in time. At 5 p.m., she has to come up with an alternate plan.

STREETWISE: Location manager Collin Smith looks for ways to bundle

STREETWISE: Location manager Collin Smith looks for ways to bundle

scenes in adjacent locations to save the show

valuable moving time.

The 2nd ADs arrive first on any shoot day and are the last to leave. “Yesterday I came in around 4:45 a.m.,” says Barbosa, who hustled to a courthouse location in downtown Manhattan to get there ahead of hundreds of background actors scheduled for an early hair and makeup call.

That’s when an additional 2nd AD especially comes in handy. “I make sure the trailers are there, that the holding area for extra actors is set up,” says Heckman, who takes turns with Barbosa being the first in. “I label and stock rooms. I meet and greet all the actors, I get them through the works,” referring to fittings, hair and makeup, and the like. Heckman sometimes even reads lines with actors, or cues them during rehearsals. “I run around a lot,” she laughs, as she excuses herself. She’s needed back on the set.

Because Blue Bloods is shot by a roster of guest directors, Michael Pressman and all the members of the directing team help bring each new director up to speed. “Our job is to service the production and take care of the director,” says Jono Oliver, the show’s other 1st AD, who works on the “odd” team along with Barbosa. Oliver explains that the first thing he does when a new guest director arrives is walk him or her through the sets. “And I introduce them to the cast if possible.”

If the director is brand new to the show, the ADs might provide previous episodes or scripts to read. “There is a period of osmosis,” says Pressman. “They meet actors and converse about things like how Tom Selleck likes to work.” Selleck works the last four days of one episode and the first four days of the next episode and then he’s gone for two weeks, which means that some directors have to shoot interior scenes first, which can potentially impact their ability to shoot exteriors on good weather days. Pressman says, “We try to prepare someone for jumping into the deep end.”

The 2nd ADs pitch in acclimating the directors too. “You talk to them a lot,” says Barbosa. “You ask them how they like to work. You get a sense of their personality. Some are very self-sufficient, some need more support. We find out how they like to do things, how they like their coffee, what time they like to come on set.”

Aspromonti says he’ll provide directors with staging tips about how actors such as Wahlberg and Moynahan tend to play their characters: “I’ll tell them stuff like, ‘When Donnie sits at his desk, he usually puts his pistol in this drawer. Bridget likes to put her jacket on the back of her chair. Little things like that.”

Oliver says he tries to be a useful conduit for the directors. “I filter quite a bit,” he says. “Some directors have their hands full. I don’t want to contact the director with needless information. I tell them what they need to know. Being a good AD means giving the right information at the right time.”

Oliver is excited to be working this week alongside director Alex Zakrzewski, who’s back for the fifth time. “It’s nice when they come back,” he says. “Then we can build on our relationship rather than start from scratch.” With regard to Zakrzewski, “I know how he likes to shoot ... quickly,” says Oliver, “and be well organized, as most directors are. He’s a lot of fun, which makes it more relaxed.”

FAMILY FEAST: (above) Barbosa (in gray sweater) makes sure all the pieces are in place for a

FAMILY FEAST: (above) Barbosa (in gray sweater) makes sure all the pieces are in place for a

Thanksgiving scene; (below) 2nd AD Regina Heckman (right) works mainly with

the actors, sometimes even reading lines with them in rehearsal.

For the second season, 15 directors directed the 22 episodes. “When directors work out well, it’s a great plus to have them return,” agrees Pressman, who takes satisfaction in running a director-friendly show. “I don’t direct the directors,” he says. “I try to give directors confidence, support, and guidance.”

Pointers also come from the location department. Since approximately half the scenes in Blue Bloods are shot on locations throughout New York, and since many out-of-town directors aren’t intimately familiar with the city, Smith, the location manager, plays a critical part in helping them showcase the city’s architectural assets and obscure neighborhood pockets. During the first season, Smith pulled off a major coup, convincing the staff at the 9/11 Memorial site to allow Blue Bloods to shoot there, making it the first scripted show to do so.

“We do our due diligence for what the director is looking for,” says Smith, a burly, soft-spoken guy who previously worked on Curb Your Enthusiasm. “We all defer to the director’s vision.”

After Smith receives a script and has determined which locations to tackle first, he sends his location scouts off. Whenever possible, they create hubs or clusters—locations in close proximity to one another—to reduce the amount of equipment to be loaded and unloaded by the crew.

Recently, his team cobbled together a hub that incorporated four different scenes—an office, a hotel lobby, a restaurant, and a street for an arrest sequence—that were within a two-block radius in upper Manhattan but projected radically different tones and looks. “You could walk down one street where it feels gentrified and turn a corner and see all these mom-and-pop shops and peeling paint,” says Smith. “We were able to push everything along. It was a good day.”

Once he’s organized enough, Smith hops into a van with the department heads for a tech scout. “There’s a lot of adjusting,” he says, for instance, sometimes the owners of locations are inflexible. “We just shot in a townhouse off Madison Avenue,” says Smith. “They had a lot of restrictions: No tape on the floor. We couldn’t use certain equipment.”

Smith is also responsible for securing permits from the city and working with the ADs to determine caterer corners and spots for background actors to obtain shelter if it’s cold or rainy or snowy. Pressman, for instance, mentions that he’s a little worried about an upcoming shoot set on a Brooklyn fishing pier. “I’m concerned that when we get to the pier, it will be five degrees out,” he says, recalling how last year, when they arrived to shoot an episode that featured a female body being dredged out of the East River, a torrential rainstorm ensued. “That poor girl froze her ass off,” recalls Pressman.

Every episode of Blue Bloods presents unique problems to solve. Right now, Oliver is preparing for a scene in which a building has an explosion that blows glass onto the street followed by billows of heavy smoke and people hanging out of windows. To ensure the scene’s authenticity, he is conducting a tech scout with the fire department to get details on such things as how the fire trucks would pull up and where the firefighters would race to first. “Of course, we may take liberties,” concedes Oliver.

When shooting stunts, which Blue Bloods does quite often, says Aspromonti, “you need to keep your mind sharp.” A car crash scene shot in Brooklyn last season, for example, required him to place background actors in the frame but out of danger. “It can be stressful,” he says. “But I like being on the front lines.”

And if there aren’t stunts to deal with, there might be several hundred extras that require wardrobe fittings, hair and makeup, and staging direction. For the pilot, hundreds of background actors playing graduating police cadets had to undergo head and facial hair trims that conformed to police guidelines. For another episode, “Model Behavior,” in which a model mysteriously collapses and falls off a runway, the directing team held model auditions, hired a runway coach and so many extras (playing runway models and audience members) that they had to devise a color coding system to keep track of everyone. “You think you’ve seen it all,” says Barbosa, “and something else comes up.