BY SCOTT FOUNDAS

FILMMAKERS' JOURNEY: Bruce Sinofsky (left) and Joe Berlinger, with Damien Echols on death row in 2009, started working on the first film of their trilogy in 1993.

(Photo Courtesy of Bob Richman)

It is the evening of August 19, 2011, and a party is under way at the Madison Hotel in downtown Memphis, Tennessee. The mood is celebratory, belying the fact that not 24 hours earlier, the three men being feted were incarcerated in a Jonesboro, Arkansas prison—two of them serving life sentences, the third on death row. The formerly condemned man, Damien Echols, waves and raises his wine glass to the documentary filmmakers Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, who look on in mild disbelief. They are reminded of another, far-less joyous occasion when Echols signaled to them across a crowded room: the moment, some 17 years earlier, when he was being led away from a courtroom in chains, having been found guilty—and sentenced to die—for the brutal murders of three 8-year-old boys.

By that point, Berlinger and Sinofsky had become convinced that Echols and his alleged co-conspirators, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley Jr. (aka the West Memphis Three), were all wrongfully accused, victims of media-fueled hysteria about satanic cultism, and of a hermetic community’s desire for swift justice. And as the filmmakers—who had arrived in the town of West Memphis, Arkansas, in the summer of 1993, the shock of the murders still fresh in the air—watched Echols disappear into a police van outside the courthouse, they knew that the movie they had spent the last year of their lives shooting was just the beginning of a much larger endeavor.

“When Joe and I got to the airport in Memphis, we looked at each other and said, ‘Whether we continue filming or not, we have to be involved in helping these guys,’” the easygoing, Lebowski-esque Sinofsky says, speaking in the kitchen of his amiably cluttered Montclair, New Jersey, home. “That was the moment, for me anyway, when I went from being a storyteller to an advocate,” adds Berlinger—as intense as Sinofsky is laid back—over breakfast the morning of the Academy Awards.

For the record, Berlinger and Sinofsky aren’t the first non-fiction filmmakers whose work contributed to the freedom of a death row inmate. In 1988, Errol Morris’ The Thin Blue Line argued so persuasively for the innocence of a man convicted of the 1976 murder of a Dallas police officer that the case was subsequently reopened and the conviction overturned. And in 1965, an up-and-coming TV director named William Friedkin similarly examined the case of a Chicago man charged with murdering a security guard during a robbery. The resulting film, The People vs. Paul Crump, was deemed instrumental in the commutation of Crump’s death sentence.

But if Berlinger and Sinofsky’s Paradise Lost trilogy seems like a singular achievement, it is partly a question of scale—the project now spans almost 20 years and more than seven hours of screen time—and largely due to the way the films themselves have increasingly become part of their own epic narrative, sparking a national advocacy movement that proved instrumental in the West Memphis Three’s dramatic reversal of fortune. Indeed, it is impossible to recount the Paradise Lost story without also reflecting on two decades worth of changes in the media, in the culture of non-fiction filmmaking, and in Berlinger and Sinofsky’s own creative partnership—a collaboration that has its roots in the New York offices of cinéma vérité pioneers Albert and David Maysles.

It was in the mid-1980s when they first met—Berlinger a former advertising executive recruited by the Maysles brothers to help boost their TV commercial business, and Sinofsky an editor who would cut together the show reels Berlinger needed for his Madison Avenue pitch meetings. “We just became very good friends right from the start, and about three years into my tenure at Maysles, I decided I wanted to aggressively pursue becoming a filmmaker,” says Berlinger. The result was Outrageous Taxi Stories (1989), a 25-minute documentary short directed by Berlinger, edited by Sinofsky, and shot by cameraman Bob Richman (another Maysles staffer who would become an important member of the Paradise Lost team).

The short traveled widely on the festival circuit, giving Berlinger and Sinofsky the confidence they needed to try their hands at something more ambitious. “With certain exceptions like Barbara Kopple, the 1980s were generally a very fallow period for the kind of ambiguous, cinéma-vérité, human portraits with dramatic structure that made the Maysles famous, like Grey Gardens and Salesman,” says Berlinger. “So Bruce and I said, ‘Let’s make one of those films.’ ” Around the same time, the friends slipped into the Lincoln Plaza Cinemas to catch a screening of The Thin Blue Line. “That was like a light bulb going off,” remembers Berlinger. “Not stylistically—because that film is as different as can be stylistically from what the Maysles were doing and what we wanted to do—but in the idea that you could actually put a documentary in the movie theater and people would go see it.”

For a year, Berlinger and Sinofsky waited for the right story to come along, until one morning they both arrived for work excitedly clutching a small New York Times story about Delbert Ward, an illiterate, upstate New York dairy farmer accused of smothering to death his brother William. “It really caught my eye because I knew this area,” recalls Berlinger, who graduated from Colgate University in the nearby town of Hamilton, New York. “That was on a Monday, and by Friday we had driven upstate and met with Delbert’s attorney,” says Sinofsky. “By Saturday, we were being chaperoned around, because the townspeople were very leery about outsiders coming in.”

In many ways, that true-crime tale, which would become Berlinger and Sinofsky’s DGA Award-winning debut feature Brother’s Keeper (1992), was an instructive primer for their work on the Paradise Lost films, particularly when it came to ingratiating themselves into a potentially inhospitable or outright hostile environment. “Joe and I often say that the work we do before we film is the most important, because it’s really about trust,” explains Sinofsky. “There’s no reason for any of these people to think that two guys from New York who are of a different faith than they are would be honest and fair and not just try to take advantage of them.”

In the case of both Brother’s Keeper and Paradise Lost, that meant leaving their cameras in the car when they first arrived on the scene and slowly earning the confidence of their subjects before ever exposing a frame of film. “We did chores,” Berlinger says of the duo’s early days on the Ward brothers’ Munnsville dairy farm. “I remember mucking out the barn. And we would spend hours just sitting in the grass with them. Maybe every 10 or 15 minutes a word would be exchanged.”

BEFORE AND AFTER: (top) Berlinger and Sinofsky shoot the first interview with Jason Baldwin after his release; (bottom) The directors show Baldwin their camera in 1993.

Photos: (top) Jonathan Silberberg; (bottom) Courtesy of Third Eye Motion Picture Co., Inc.

When they landed in West Memphis in 1993, Berlinger and Sinofsky drew on that grass-sitting, barn-mucking experience to secure the participation of all three of the accused, their families, the victims’ families, and extraordinary access to film inside the courtroom of Judge David Burnett during each of two ensuing trials. In their first meeting with Todd and Diane Moore, the parents of victim Michael Moore, the filmmakers discovered that the Moores didn’t want to appear in a film. “And we said, ‘Look, we understand the sensitivity here. We’d like you to be in our film, but we’ll never ask you again,’ ” says Sinofsky. A few weeks later, when they set out to film a memorable afternoon of target practice with Mark Byers, stepfather of victim Christopher Byers, Todd Moore asked if he could tag along. “And that was him breaking the ice, because by then he had decided that we were OK.”

When it came to filming the trials, the directors called in a favor from an old friend. “We actually had the judge from Brother’s Keeper call [Burnett] to let him know that we were OK, that we weren’t going to get in the way of everything,” says Sinofsky. “Then we met Gary Gitchell, the police captain, and John Fogelman and Brent Davis, the prosecutors. The agreement was that if anyone on any side objected, cameras would not be allowed in the courtroom. And I have to say that the work Joe and I did in talking to them, and massaging them in a certain way, was some of our best work, because without that access it just wouldn’t have been the same film.”

Berlinger and Sinofsky first learned about the West Memphis case via an AP wire story sent to them by HBO’s legendary documentary chief, Sheila Nevins, who had hired the directors in the wake of Brother’s Keeper to make a film about the American funeral industry. “We thought we were going down there because these guys were guilty, and the first people we met were the families of the victims and the police and the prosecutors. So it was all very, very against the West Memphis Three,” says Sinofsky. “Our first feeling that things weren’t quite right came when we started meeting the families of Jason, Damien, and Jessie, and then their attorneys. Then, after we filmed Jason, Damien, and Jessie themselves, it was clear that they may have been innocent and that this was a rush to justice. Joe and I would talk a lot in our dumpy rooms at the Ramada Inn off I-55, and we said, ‘Well, we should go back to Sheila and let her know that there’s something going on here that we need to look into,’ and she agreed.”

It was in that same hotel, Sinofsky recalls, that he and Berlinger began conceiving of a look and a structure for the film. “We knew that a crime took place and there was going to be a trial, so we had some sort of structure there,” he says. “But getting to know all the parties was always important to us. We would shoot the trial during the day and then we would go back to a lawyer’s office, or we would meet Damien’s family—things like that.” They even hired a helicopter to shoot 35 mm aerial footage of the crime scene and the surrounding area, to orient viewers geographically, but also to lend the film some of the visual dynamism of a narrative feature. “We use some of the artifice of fiction in non-fiction,” says Sinofsky. “There’s a beginning, middle, and an end. There’s rising and falling action.”

Later, in the editing room, the directors (who also shared editing credit) would build short scenes, or “lifts,” out of their 16 mm dailies. “Suddenly, you’ve got 18 or 20 scenes, and then you start thinking, ‘Well, this one would go well with this one,’ ” says Sinofsky.

Broadcast in June of 1996, the first Paradise Lost, subtitled The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills, recounts the gruesome details of the crime, a botched investigation that includes lost evidence and coerced confessions, and an often surreal trial in which a parade of unconvincing character witnesses and correspondence-course experts on the occult vilify the three accused in lieu of any physical evidence. The tone is appropriately austere, but as in Brother’s Keeper, Berlinger and Sinofsky find their own way into the material, observing many of the tenets of cinéma vérité while allowing for on-camera interviews and for an off-camera intimacy with their subjects that some documentary purists would deem a conflict of interest. In a controversial decision, the directors provided all of the families, many of whom were living at or near the poverty line, with modest honoraria for their participation in the project. In yet another ethically complicated twist, the team found themselves at the center of the story when Mark Byers gave them as a gift a used hunting knife that turned out to have dried blood in its hinges. (They promptly turned the knife over to the police and it was entered into evidence.)

“We are disciples of the Maysles style of acquiring footage, which means that you have faith in the unfolding story,” notes Berlinger. “People don’t realize just what an act of faith that is: you have some inciting incident like a murder, and you follow it in the hope that it can be crafted into something satisfying. What if the West Memphis Three had taken a plea early on? What if Delbert Ward had never gone to trial?” But Berlinger is quick to add that he and Sinofsky part ways with their storied mentors on several key levels. “First of all, the Maysleses resisted using the term ‘director’ and believed that you could capture an objective reality, and I think there’s no such thing as objectivity in cinema, including documentary making,” he says. “The choice of camera angle, the 8,000 decisions you make in the editing room ... I think filmmaking—all media—is shaped by the perceptions and psyche of the person creating it. Most importantly, I think that any time you enter people’s lives and you follow their story, part of the story becomes the relationship between subjects and filmmakers.”

When Berlinger and Sinofsky returned to West Memphis, however, to begin work on Paradise Lost 2: Revelations in 2000, they found that following the first film’s broadcast, many of those relationships were now fraught with suspicion and unease. “I think they felt betrayed, because there was a suggestion that maybe these three guys were innocent,” Sinofsky says of the victims’ families, all of whom save for Mark Byers declined to participate in the second film. Nor were they the only ones. Cameras were now banned in the courtroom as well, even as the defense team appealing Echols’ conviction found itself entering the first Paradise Lost film into evidence. So the directors had to rely mostly on third-party news coverage to tell the story, plus black-and-white-tinted flashbacks to the first film that Berlinger admits now make him cringe.

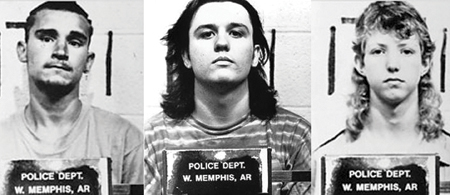

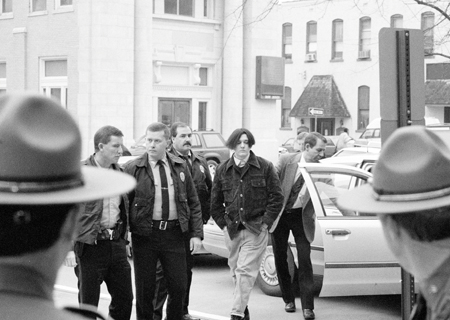

LIFE AND DEATH: (top) The West Memphis Three (left to right): Jessie Misskelley Jr., Damien Echols, and Jason Baldwin; (bottom) Echols being escorted to his trial in 1994 for a crime he didn’t commit

LIFE AND DEATH: (top) The West Memphis Three (left to right): Jessie Misskelley Jr., Damien Echols, and Jason Baldwin; (bottom) Echols being escorted to his trial in 1994 for a crime he didn’t commit

Photos: (top) Courtesy of HBO, (bottom) Joe Berlinger

“The second film was driven purely by an advocacy instinct, and in many ways it’s an advocacy film in search of a story, and I think it’s by far the weakest of the three,” he says candidly. And yet, if Revelations falls short of the promise of its title, it remains undeniably fascinating for its introduction of the burgeoning West Memphis Three support group, a nationwide community of like-minded justice seekers, connected via the Internet, who became aware of the case through the first Paradise Lost film, adding yet another self-reflexive dimension to the series’ ever-lengthening hall of mirrors.

Asked how they’ve worked so well together for so long, Sinofsky says that he and Berlinger have always benefited from a shared vision of whatever project they happen to be working on. They also have a longstanding rule: in the cutting room, each director is allowed three unilateral decisions—or “swords” as Sinofsky calls them—that, if invoked, must remain unchallenged by the other party. “And in all the films that we’ve made, we’ve only done it once, on Paradise Lost 2,” he says. “There was something that I thought was kind of a double ending. It could have stayed the way it was, but I called in a sword there.”

Following Paradise Lost 2, Berlinger and Sinofsky went their separate ways for a while, with Berlinger directing The Blair Witch Project sequel Book of Shadows (2000) and Sinofsky the PBS Sun Records tribute documentary Good Rockin’ Tonight (2001). They reunited in 2004 for the acclaimed Metallica: Some Kind of Monster, which follows the influential heavy metal band (whose music features prominently in the Paradise Lost films) through the recording of their latest album and myriad personal and professional crises.

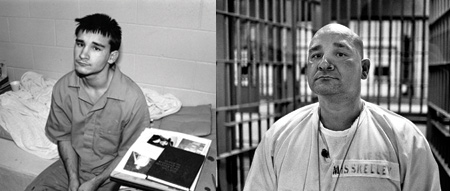

Jessie Misskelley Jr. in his cell at age 17 in 1993, was sentenced to life plus 40 years in prison, and (right) in jail at age 34 in 2010.

Jessie Misskelley Jr. in his cell at age 17 in 1993, was sentenced to life plus 40 years in prison, and (right) in jail at age 34 in 2010.

During those same years, new developments in the West Memphis Three case were few and far between, mostly involving further appeals by Echols and his co-defendants. “Unlike filming an unfolding murder trial, the appeals process is very un-cinematic—it’s the filing of papers,” observes Berlinger, who began working with Sinofsky on the third film as early as 2004. But a 2007 press conference, at which the now high-powered defense team (including O.J. Simpson “dream team” vet Barry Scheck) presented DNA evidence that excluded their clients from the crime scene, gave the filmmakers what Sinofsky calls “the binding for the book.”

Still, Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory (nominated for a DGA and Academy Award) remained the most difficult film in the series to structure, due to the sheer amount of time (11 years) that had elapsed since Paradise Lost 2, and the inherent challenge of making a movie that would be accessible to audiences both old and new. “The beginning of the third film—the first act—is really allowing people to see what the first two were about, because we needed it to be a stand-alone film,” says Sinofsky. “We didn’t want to just rehash the same information, but it was important that somebody who had never seen the first or second film could watch the third one and know what had happened.” To that end, the filmmakers brought their old Steenbeck editing equipment out of storage and revisited their extensive archive of 16 mm workprints and dailies, whenever possible selecting previously unseen footage to tell the back story.

Then Berlinger had a “eureka” moment: He remembered he had also kept video copies of all the local media coverage of the case dating back to 1993.

“We started looking at the press coverage and realized that it was a perfect narrative device and a perfect way to express what I think is one of the major themes of the third film, which is the power of the media to shape perceptions,” says Berlinger. “The media, to me, is very much the reason these guys were convicted. In Paradise Lost 3, you see how extremely negative those early newscasts were, focusing on devil worshipping and the like. Then you see some of these same journalists continuing with the story over the decades, you see them getting older, more professional, and the sets becoming more professional. And you also see that the reporting goes from being very one-sided, to, around the mid-2000s—especially when all the new evidence starts coming out—favoring the idea that these guys are potentially innocent.”

In other ways, too, time becomes the dominant concern of Paradise Lost 3—both the time that has passed since the series first began, and the little time that remains for Echols, barring a reversal of his sentence. In new jailhouse interviews, the film’s subjects appear no longer as the confused teenagers they once were, but rather as men in their early 30s, made wise beyond their years by the terrible fate they have suffered. Echols himself seems somehow even older, with a receding hairline and premature arthritis. Misskelley, meanwhile, has had an actual clock tattooed on his shaved head—minus the hands, to be added later, he says optimistically, showing the time of his eventual release. And then there are Berlinger and Sinofsky’s grainy, scratchy 16 mm dailies, which periodically interrupt the crisp, high-definition video images in Paradise Lost 3 to tell yet another story—that of the evolution of documentary filmmaking from an analog to a digital medium.

“Just physically being able to touch a splice and open a splice was nice—I missed it,” says Sinofsky, while noting that, in most respects, the move from film to digital has had little impact on the way he, Berlinger, and cameraman Richman go about their work. “Bob shoots the same way with a digital camera—a mounted one,” he says. “We’ve sometimes used those smaller cameras, but nothing’s better for Bob than having a shoulder-mounted camera. He’s just got a magical eye. Joe and I feel with him like there’s a wiretap running from our heads to his camera. I can feel what he’s shooting by the turning of the focus.”

“I think the first Paradise Lost was shot at the end of a certain era,” observes Berlinger, pointing to another, more substantial change in the documentary realm. “If this film was shot a couple of years later, we wouldn’t have gotten the same access. The film was made prior to the O.J. Simpson trial, and the O.J. trial was a watershed event in American culture, in which the American public and the media realized that hanging on every salacious moment of a terrible crime was good television. Court TV had just started but wasn’t a phenomenon; the 24-hour news cycle hadn’t yet kicked in. I think if this murder had happened five years ago, by the time we showed up there would have been 80 satellite trucks there, the family members would have media handlers and agents and other representatives. So the movie happened at precisely the right moment, in which the combination of the story, the characters, and the access we got produced something really spectacular.”

Berlinger and Sinofsky rushed to complete work on Paradise Lost 3 in time for a fall 2011 premiere, the idea being to reignite interest in the case in advance of a scheduled December evidentiary hearing that seemed, in, light of the new DNA evidence—as well as allegations of jury misconduct—like it would finally lead to new trials for the West Memphis Three. In August, they were already well into postproduction, with a rough cut of the film submitted to various fall film festivals, when they received word that a plea deal was imminent and hurriedly traveled back to West Memphis to shoot a new ending to the film. "'Joe got off a phone call and said, ‘Something's happening on Friday and we have to get there now,'" recalls Sinofsky. "'They weren't specific about what was going to happen, but we had a feeling. So we flew down on Thursday, drove down to Jonesboro, met up with their attorneys at a restaurant that night, and we pretty much knew by the end of the evening that these guys were going to get out. We didn't sleep much that night."

Berlinger and Sinofsky are convinced that this sea change in the attitude of the local media—and local residents—coming after a decade of steadily mounting pressure from pro-West Memphis Three organizations, and from celebrity activists such as Johnny Depp and Eddie Vedder, set the stage for the deal that ultimately saw Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley walk free. (The deal, known as an "'Alford" plea, allowed the three defendants to maintain their innocence while nevertheless entering guilty pleas into the official record.) It was a bittersweet ending for the directors, who both say that the experience of the Paradise Lost films changed them profoundly as people, and who had hoped—and still hope—to see their subjects fully exonerated. But if and when that day comes, this time Berlinger and Sinofsky don't expect to be filming it. They're now happy to pass the torch to others, such as producer Peter Jackson and director Amy Berg, whose own West Memphis Three documentary, West of Memphis, premiered at this year's Sundance Film Festival. (A dramatic version of the story, directed by Atom Egoyan starring Reese Witherspoon and Colin Firth, is also in the works.)

"'As long as there's attention on these three guys, that's great," says Sinofsky, who is now contemplating an early retirement in the south of France, where he and his wife have a home. "'You know, the idea of going back in five years or so to see how their lives have changed—I think people would want to see that. But I don't want to feel like every time I see them I have to have a camera there. I want them to have normal, regular lives, as much as they can for people who've spent that much time in jail or been on death row."

Berlinger, meanwhile, has several fiction screenplays in development and hopes to continue shedding light on matters of injustice and disenfranchisement in films such as 2009's Crude, about the oil pollution of the Ecuadorian Amazon. "'That tension between advocacy and journalism, and whether they can co-exist, to me is one of the fundamental questions of what I do," he says. "'Storytelling, especially if you want to lend your documentary a certain dramatic structure—in the Aristotelian sense of the term—has certain demands. When you're trying to be a journalist, there are certain demands of balance. And when you're trying to be an advocate, there are certain demands of making sure the audience understands your point of view about the subject matter you're trying to be an advocate for. And I don't have a clear answer as to what that balance is, and I think that was the challenge of the Paradise Lost series and that's the challenge of the kinds of films I tend to gravitate towards."