BY TERRENCE RAFFERTY

(Credit: Kobal)

(Credit: Kobal)

I am not an artist.” Fritz Lang, the director of Metropolis (1927), M (1931), and The Big Heat (1953), was not known as a humble man, but on the set of his last film, The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960), he said that very thing to, of all people, an actor. He elaborated: “I am a craftsman.” Perhaps the great filmmaker, then nearing 70, was simply feeling weary and a little low, or maybe he meant that on this picture, with its skimpy budget, a craftsman was all he could hope to be. But although Lang surely was a film artist, and surely knew it, there’s a lot of truth in his self-assessment: He was—from the beginning of his career in the German silent cinema, through two busy decades in Hollywood, to this modest end, back in Germany—always the sort of filmmaker whose art was his craft. In Germany during the ’20s, he made elaborate, complex, hugely ambitious movies, mostly for the legendary UFA studio. In America, he was never to work on such a grand scale or with such consistent support from his producers: The 22 pictures he directed in Hollywood between 1936 (Fury) and 1956 (Beyond a Reasonable Doubt) were almost exclusively genre pieces—many thrillers, a handful of Westerns—and he made them for no fewer than nine different studios. His craftsmanship was his salvation. Fritz Lang thought big, but he knew how to work small.

Adaptability is close to the last thing you’d expect to find in a filmmaker such as Lang, who cultivated the image of the tyrannical Teutonic filmmaker and, by all accounts, frequently lived up to it. (The monocle he sported for his entire career contributed mightily to his general air of fearsomeness.) And among the many European directors who migrated to the United States in the ’20s, ’30s and ’40s, Lang was perhaps the one with the most prestige to lose: unlike Billy Wilder, William Wyler, and Fred Zinnemann, he arrived on our shores with a big name and an already formidable body of work. When Lang landed in Hollywood, after fleeing the Third Reich and directing one picture (Liliom, 1934) in France, he had to adjust to the American way of moviemaking, in which he would have exponentially less control over his art than he had had in Germany. He was by temperament a survivor, though, and he’d already met the most important creative challenge of his generation of filmmakers—the transition from silence to sound. As far as dealing with overbearing studio bosses went, even the heavy hand of, say, Louis B. Mayer couldn’t compare to what he’d left behind—in a hurry—in Germany, where Hitler and Goebbels would have been looking over his shoulder.

Lang is in fact practically a one-man history of cinema from 1920 to 1960, a director who weathered a remarkable amount of turbulence both in society and in the constantly evolving medium in which he labored, and who managed, through it all, to maintain a master craftsman’s sang-froid. Even in the glory days of Weimar filmmaking, his technique was unusually flexible: his style changed, subtly, as cinematic fashions did. In early movies such as Destiny (1921) and the electrifying Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922), he relies heavily on iris effects to focus the viewer’s attention and to vary the transitions between scenes. But by the time of his last silents, Metropolis, Spies (1928), and Woman in the Moon (1929), that technique had all but disappeared, and in its place was a speedier, more kinetic, and more modern-seeming sort of editing rhythm. In his silent films, Lang rarely moved the camera, but his first talkies, M and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933), are full of gracefully executed tracks and pans. It’s as if he had realized that with dialogue his editing options were more limited and he needed other ways to create a sense of dynamism, the relentless forward movement that was, and would remain, the most striking characteristic of his movies. Francois Truffaut once wrote, “There is only one word to describe Lang’s style: inexorable.”

Lang gravitated toward stories that lent themselves to brisk pacing. Unlike his nearest rivals in the German film industry, F.W. Murnau and G.W. Pabst, he had next to no interest in moody, atmospheric character studies; Lang’s taste always ran to pulp. His very early The Spiders (1919) is a wildly improbable adventure tale of the Indiana Jones ripping-yarn type, set largely in Central America and featuring (among other juvenile tropes) messages in bottles, lost treasures, and quite a few gaudily costumed Native American “savages.” The Mabuse pictures and Spies are about mad, world-domination-craving archcriminals; Lang borrowed some elements from the zesty silent film serials of Louis Feuillade, but used his wily villains to greater satiric effect. The insane title character of The Testament of Dr. Mabuse was close enough to certain real-life lunatics of 1933 Germany that the film was banned by the Reich. Metropolis and Woman in the Moon are science fiction, a genre then gaining popularity in the pulps. M, though soberer than the others, is nonetheless based on a tabloid-sensational story—the pursuit of a notorious child-murderer in Düsseldorf. Even his epic Die Nibelungen (1924), derived from the same Germanic folklore and legends that inspired Wagner’s Ring cycle, becomes, in Lang’s telling, a kind of mythic pulp. The spectacle of Siegfried slaying the dragon is as exciting as any of the breathless derring-do of The Spiders, and just about as nutty.

Lang’s predilection for trash is, weirdly, one of the qualities that makes him seem so modern in our new century: the distinction between high art and low didn’t trouble him then any more than it does Brian De Palma, Quentin Tarantino, or Martin Scorsese today. For him, as for his craftiest successors, a film’s story is primarily a stimulus to visual invention; his imagination was overwhelmingly pictorial. Lang, who was born in Vienna and studied architecture and painting as a young man before drifting into the movie business, his training in those more traditional arts is plenty obvious in his approach to filmmaking. The production design and art direction of his pictures is always impeccable, whether on the monumental scale of Metropolis or on the less imposing one of his Hollywood thrillers and noirs, and the shots are always meticulously composed. The American critic Otis Ferguson, who profiled Lang in The New Republic in 1941, put it succinctly: “He is a careful, careful man.”

What he was not, ever, was a man with a message. He was the type of filmmaker whose art emerged from his solutions to specific problems of narrative and visual representation: Meanings, if there were any, could take care of themselves. (And if there weren’t, at least the pictures would look good.) He did, however, have a kind of running theme, a worldview—perhaps shaped by the decadence of the Weimar period—that was evident in practically every film he made in Germany and in a surprising number of his American pictures, too. He kept returning, over and over, to the idea that the boundary separating respectability and criminality is fluid, even illusory. Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, a devastating take (in pulp terms) on the hysteria of German society in the ’20s, was his first exploration of the theme: the title fiend, a master of disguise, is both a distinguished psychiatrist and a world-class felon, whose misdeeds range from cheating at cards to currency manipulation to kidnapping and murder. The villain of Spies is cut from the same cloth, with a more exotic-sounding name (Haghi) and a more sinister “respectable” occupation—banker. In the futuristic Metropolis, society itself has become so brazenly criminal that the city’s overlords can commit their outrages with impunity, and with no need for secrecy or disguise. They don’t even have to hypnotize people, as Mabuse does, because the workers are so tired they might as well be walking in their sleep.

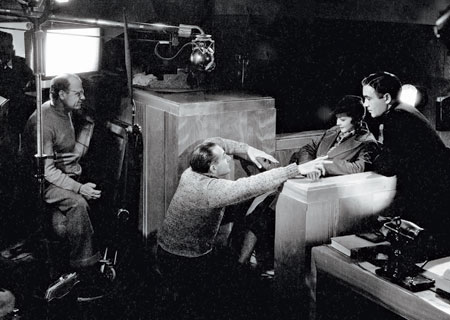

Sylvia Sidney and Bruce Cabot in Lang’s first Hollywood picture, Fury (Credit: Photofest)

Sylvia Sidney and Bruce Cabot in Lang’s first Hollywood picture, Fury (Credit: Photofest)

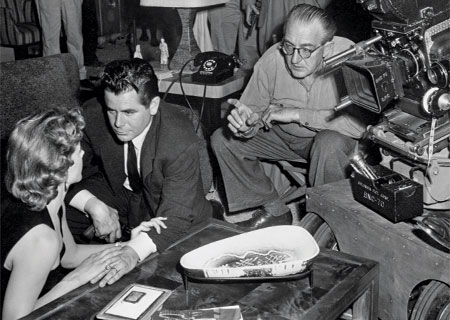

Lang’s best American film, The Big Heat, with Glenn Ford and Gloria Grahame (Credit: AMPAS)

Lang’s best American film, The Big Heat, with Glenn Ford and Gloria Grahame (Credit: AMPAS)

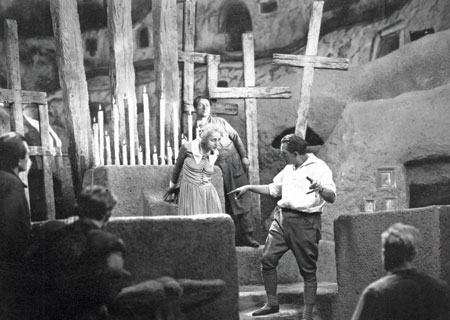

The director’s monumental staging on the futuristic Metropolis. (Credit: Photofest)

The director’s monumental staging on the futuristic Metropolis. (Credit: Photofest)

The most elegant elaboration of the director’s cynicism about society, though, is M, in which the murders perpetrated by one small, frightened, self-loathing pedophile create a sort of unspoken common cause for a city’s ruling class and its criminal class. Each, for its different reasons, needs to get the child-killer off the streets. Lang’s direction emphasizes the similarities between the crooks and the upholders of the law. In one virtuoso passage, Lang employs (as he rarely did) Soviet-style parallel montage, cutting back and forth between the two groups as they hash out their strategies for catching the monster. And the film’s climactic sequence, in which the killer (Peter Lorre, in his first movie role) is put on trial by the thugs who have captured him, becomes in Lang’s staging an ominous, disquieting parody of the very processes of the law.

It’s not unusual, perhaps, for artists (or even craftsmen) to feel a measure of ambivalence about respectability; society doesn’t always consider their chosen profession entirely reputable. Within a couple of years of making

M, Lang was himself a man on the run, slipping across the border into France in the dead of night after, he always claimed, having been offered the highly dubious opportunity to run the Nazis’ film industry. (Much in Lang’s version of this story is unconfirmed, including even the offer itself, and he probably embellished some facts to make his narrative more breathlessly cinematic. But it’s indisputable that he fled Germany, and he apparently left most of his wealth behind.) And when he arrived, more or less for good, in Hollywood, he brought his ambivalence with him, and it continued to serve him well.

The first two films he directed in America, Fury (1936) and You Only Live Once (1937), were melodramas about social injustice. In Fury, an innocent man is apparently lynched by the good citizens of an ordinary American town. He survives, and turns vengeful, as bloodthirsty in his way as the mob that tried to kill him. In You Only Live Once, an ex-con tries to go straight, but society makes it impossible for him and he takes it on the lam with the woman he loves. (The movie is the earliest version of the story of Bonnie and Clyde.) Neither film is quite up to his best German work, but the subjects suit him, and both are exceptionally well-made: the crowd scenes in Fury are as brilliantly staged as anything in Metropolis, and the light-and-shadow compositions of You Only Live Once sustain a pervasive mood of romantic fatalism, which recalls the somber tone of Destiny.

What’s fascinating about these first Hollywood films is that they show how canny Lang was about finding ways to express himself in his changed and reduced circumstances. It’s a talent film artists have to have, if they are not to decline into bitterness and regret, as even some of the greatest, like D.W. Griffith, did. In the studio system, Lang was almost never able to initiate his own projects as he had in Germany and usually couldn’t control the final editing and scoring of the films he made, but the best of them are unmistakably Fritz Lang movies, and even the worst are competent and watchable. For the most part, he stuck to pulp stories—never a liability in Hollywood. And he was able to adapt many of the techniques he’d mastered in Germany to different purposes in the New World. One of the small pleasures of watching a low-budget thriller such as House by the River (1950) is noticing how he uses high-expressionist lighting, with deep, dark shadows, to mask the inadequacies of his B-list actors. (Louis Hayward, Jane Wyatt, and Lee Bowman are the leads, and the lighting is a mercy to their performances.) No director survives long in Hollywood without the imagination to make virtues out of the direst necessities, and Lang, happily, had imagination to burn.

The American movies are, inevitably, a mixed bag. Lang had loved Westerns since his youth, but his three excursions into the genre, beginning with The Return of Frank James in 1940, aren’t particularly memorable—although his mighty peculiar 1952 Rancho Notorious has its partisans, most of them French, and there’s a dopey charm to his splashy, good-humored Western Union (1941). The Westerns give further evidence of his adaptability: Shooting in color didn’t faze him any more than the introduction of sound had. But he was a man of interiors, really; tight spaces suited him better. In the ’40s he also made some films about the war that was going on back in Europe. Of those, perhaps predictably, the most serious (Hangmen Also Die! 1943) is the weakest, and the pulpiest (Man Hunt, 1941) is by far the best. Man Hunt, about an English sportsman who is accused of trying to assassinate the Fuhrer, is a chase picture in the mold of Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps (1935), and one of the best of its kind not made by the Master of Suspense himself—not surprisingly, since Hitchcock had picked up a good deal of his own remarkable technique from German silent filmmakers such as Lang. By the mid-’40s, a new, gloomier kind of thriller mood was becoming fashionable in Hollywood: the style we later learned to call film noir, which also had its roots in the German silents and therefore was a very comfortable fit for Lang’s talents. Noir kept him busy and productive for the last dozen years of his American career.

The genre didn’t use all his skills, of course: no large sets, no complicated crowd scenes. Lang became a miniaturist, exploring the small, mean emotions of men and women in the small, mean rooms they lived in. His first Hollywood noir, The Woman in the Window (1944), almost revels in its own limitations. It’s a femme fatale melodrama with few characters—only three that matter—and a notably single-minded focus on its basic themes of jealousy and betrayal. Literally single-minded, as it turns out: In the end we discover that all the action has been taking place inside the head of the protagonist. Even in film noir, you can’t get more claustrophobic than that.

What’s amazing about Lang’s noirs is that he creates an almost palpable sense of confinement without resorting very frequently to the use of close-ups to restrict the space around the characters. All throughout his career, he had favored medium shots for even the most highly charged emotional moments, and clearly saw no reason to change his lifelong practice at this stage: He knew he could get the effects he wanted without shoving his camera directly into his actors’ faces. So in his best noirs—Woman in the Window, While the City Sleeps (1956), and, especially, The Big Heat—the melodramatic action seems both appropriately intense and curiously detached. One of the many reasons The Big Heat is Lang’s best American film is that the acting style of its star, Glenn Ford, has that same odd mixture of qualities. The story, like that of Fury, is about a man who becomes obsessed with revenge: both Ford’s performance and Lang’s direction seem to simmer, like the coffee Lee Marvin hurls in Gloria Grahame’s face. The movie itself is about the wisdom of keeping the hot stuff, like rage, under strict control. As Lang (and Ford) knew, professionalism—craftsmanship—is among the most powerful ways of holding the more destructive, and self-destructive, emotions at bay.

There’s no evidence that Lang felt terribly disappointed or angry about the ups and downs of his career as an expatriate, but he’s bound to have realized that his work as an artist would have been quite different had the awful political reality of Nazism not intervened. And when he returned to Germany in the late ’50s to make a couple of florid pulp adventure pictures of The Spiders kind (The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Indian Tomb, both 1959) and that last Mabuse film, it must have struck him that everything, in the nearly 30 years he’d been away, had changed for good, including himself, that he would never again be a man who could make a Metropolis, an M. For whatever reasons, he retired from filmmaking, resurfacing only briefly, in 1963, to play a version of himself in Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt, which is about the death of the epic sensibility and the passing of the kind of artist the younger Fritz Lang had been. Lang’s graceful performance (he wrote most of his own dialogue) shows that he shares Godard’s view, but he looks strangely serene, as if he were in on a secret. Maybe what put that faint, wry smile on his face was his conviction that while art may come and go, craftsmanship is eternal. Inexorable, even.