DVD Classics

By Robert Abele

It’s no small feat for a movie studio to reach the 100-year mark, and this year represents that milestone for two of the oldest and consistently successful of the majors, Universal and Paramount, both founded in 1912. All year long, the two studios will be separately commemorating this event with debuts of classic films on Blu-ray, and in Universal’s case, restoring some of the biggest titles in its library.

One irony about these two sharing a centennial is that most of Paramount’s pre-1950 movies are owned by Universal, after MCA purchased them in the Eisenhower era before subsequently acquiring Universal in 1962. But that hasn’t prevented Paramount from kicking off its banner year in high style with the Blu-ray/DVD release of a key title still in its library: the first best picture Oscar winner, William Wellman’s 1927 war classic Wings. A painstaking frame-by-frame restoration that had to be worked off a marred duplicate negative from the studio’s archives—the original was lost years ago—this significant release does more than dust off a classic: it helps recapture the grandeur of silent film for the home theater by boasting a full orchestral soundtrack of the original score, as well as audio genius Ben Burtt’s layering of World War I sound effects.

William Wellman on Wings (1927)

William Wellman on Wings (1927)

What clinches the experience, however, is Wellman’s commitment to aerial spectacle in telling the World War I story of two male American fighter pilots (Buddy Rogers and Richard Arlen) who love the same woman (Clara Bow) back home. Our computer-generated age has inured most moviegoers to the dazzle of digital when it comes to filmic flight, but in the late 1920s, Wellman—who’d been a pilot himself during the war—sought the breathtaking verisimilitude of real planes maneuvering in the clouds (and among each other). To that end, Wellman not only utilized a combination of movie stunt pilots and Army airmen, but the piloting capabilities of his lead actors as well. Rogers had never been in a plane before learning to fly for Wings, and on top of that he was asked to manipulate a mounted camera to capture his own exhilarating, undeniably airborne close-ups. Though the emotional terrain of the story is determinedly cornball, the physical liftoff Wellman gets from the flying sequences remains thrilling today.

Universal also put out its own monumental battle classic on Blu-ray for the first time this year, but of a decidedly more somber and critical stripe: Lewis Milestone’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), based on Erich Maria Remarque’s pacifist novel, and the first talkie to win best picture. With grim patience, we see how a band of young German enlistees (notably star Lew Ayres)—spurred to fight by a professor’s hawkish speech as crisp new recruits march outside his window—begin to view war as frightening, ugly, and meaningless, mostly a path to death strewn with mud, blood, and vermin.

Lewis Milestone on All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

Lewis Milestone on All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

It’s intriguing to note the ways Milestone and Wellman (both Guild founders) in their respective films use camera placement to lay down a cinematic language for different tones of a war story. Whereas Wellman’s rah-rah scenario benefited by filming from high vantage points to capture heroic acts with breathtaking scope, Milestone sought out trench-level points of view for claustrophobic combat terror and famously panned across soldiers being mowed down by machine guns to convey war’s capacity for instant, unforgiving carnage. There still may not be as powerful a one-two punch in anti-war movie history as Milestone’s ending: an entrenched soldier killed as his hand reaches for a butterfly, followed by a haunting image of an earlier shot of scared young faces looking back at us, superimposed over a field of graves.

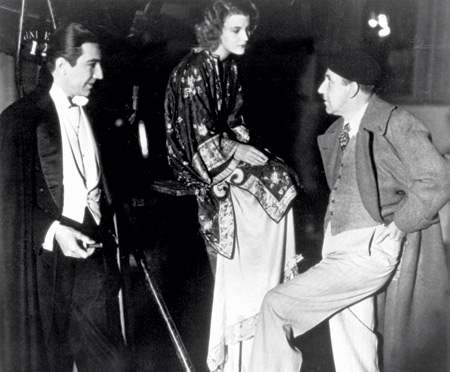

Since Universal has retained its premier titles over the years, its list of films scheduled for restoration and home video release this year is notable in its inclusion of the work of the seminal directors who helped secure the studio’s reputation as the place for horror: Tod Browning with Dracula and James Whale with Frankenstein. These 1931 films–long-established classics of the genre—are models of visual atmosphere and tonal dread, but they also stand as fascinating exemplars of the two different approaches to the monster genre.

Monumentally scary to audiences upon release, it’s now hard to look at Browning’s deliciously unfaithful adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel as anything but a creepy exercise in mannered derangement, from the cobwebbed grandeur of those castle sets to the polite lunacy dripping from Bela Lugosi’s iconic performance as the count. As the action shifts from the fiend’s Transylvania mountaintop to a bite-beset London, it becomes essentially a plague movie, all fear and containment (laced with inhuman desire). Find the menace, and stop him/it/whatever. Whale, meanwhile, pulls off the sneaky trick of initially frightening the audience with the unconscionably sinister doings of Colin Clive’s maniacal doctor—grave robbing, brain theft, reanimation—then complicating things emotionally when Boris Karloff’s masterful performance as the misunderstood creature starts to get under your skin. By the end, when the mob has become scarier than the object of their outrage, Frankenstein is a full-on father-son tragedy, an early masterpiece of psychological horror. Between Browning’s nightmare-inducing technique and Whale’s skill with the human side of the macabre, Universal’s plans for restoring these titles will be welcome, indeed.

Alfred Hitchcock on To Catch a Thief (1955)

Alfred Hitchcock on To Catch a Thief (1955)

Also on tap from Universal later in 2012 will be the eagerly awaited restoration of Steven Spielberg’s own monster classic, Jaws, followed by the 1975 blockbuster’s debut on Blu-ray. (ET: The Extraterrestrial [1982] and Schindler’s List [1993] will also get Blu-ray releases.) If Frankenstein and Dracula exemplify the monochromatic stillness of cinema’s early wave of fright films, Jaws was a glimpse at the horror film’s mainstream future: pulse-pounding pace, tongue-in-cheek humor, rich characters, unafraid to gross you out. Spielberg seemed to leave nothing off the table in his symphonic approach to mass entertainment—even his cutaways and inserts show dynamic camera placement and movement—and it served to remind moviegoers (and beach lovers) how much two hours in a darkened theater could play havoc with their deepest fears.

Of course, Alfred Hitchcock was Hollywood’s previously acknowledged master of manipulation. Before Jaws, the last great nature-kills movie was his Universal hit The Birds (1963). Spielberg has even acknowledged that because of the production’s malfunctioning mechanical shark he was forced to hint at the marauding Great White for huge swaths of the picture, thus turning Jaws into more of an unseen-terror Hitchcock-style film than a conventional monster flick.

Although Hitchcock figured prominently at both Universal and Paramount over the years (the tremendously influential Psycho was released by Paramount and later acquired by Universal), only Paramount has the venerated director in its centennial plans. In March, they released his 1955 lark To Catch a Thief on Blu-ray, the only film from his 1950s output for the studio that they still own. (Hitchcock himself owned the others—Rear Window, The Trouble With Harry, The Man Who Knew Too Much, and Vertigo—which were re-released theatrically with great fanfare by Universal in the mid-’80s.) In Thief, Cary Grant and Grace Kelly were an indisputably attractive pairing—the bronze and the beautiful—for the director’s south-of-France romp about a retired cat burglar (Grant) who must clear his name when a string of jewel robberies puts him in the spotlight again. It’s more luxuriant than pulse-quickening, but the bubbly innuendo, picturesque Riviera locales, and Oscar-winning VistaVision cinematography—Hitchcock’s first use of Paramount’s patented large-format process—still make for pleasurable distractions.

Paramount has a juicier release in the Blu-ray of Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974), out in April. The gifted Polish-born chronicler of barely submerged menace had already made a name for himself at the studio with his first Hollywood film—the 1968 chiller Rosemary’s Baby—and with Robert Towne’s layered, witty, and historically trenchant screenplay found another outlet for his brand of morally queasy suspense. Polanski noir-ishly evoked a 1930s Los Angeles where a smart-ass private eye (Jack Nicholson) with a nose for investigating corruption comes to realize he’s hardly a match for the machinations of the city’s rich and powerful. And since the early ’70s were a fertile period for world-weary paranoia in cinema, the corrosive punch of Polanski’s vision—wherein the search for truth is both eye-opening and dooming—fit in perfectly with other bone-chilling Paramount suspensers of the era such as Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation and Alan J. Pakula’s The Parallax View (both 1974). These were films built on the visual weight posed by a single individual surrounded by large, empty spaces, or who is sharing a scene with another character but feeling bewildered and alone.

Tod Browning on Dracula (1931)

Tod Browning on Dracula (1931)

Wings and Chinatown are standouts in Paramount’s plans this year, but for the celebration of its storied past, cinephiles would have welcomed other studio-defining work such as Josef von Sternberg’s baroquely fascinating, erotically charged Marlene Dietrich vehicles such as Morocco (1930) or The Scarlet Empress (1934); or urbane maestro Ernst Lubitsch’s sophisticated sex comedies Trouble in Paradise and One Hour with You (both 1932). The great Leo McCarey made some of his finest films for Paramount in the ’30s, from Duck Soup (1933, the Marx Brothers’ purest expression of lunacy), to the enchanting Charles Laughton comedy Ruggles of Red Gap (1935), and the emotionally devastating tale of society’s neglect of the aged, Make Way for Tomorrow (1937). But to find these titles, not to mention the inventive Preston Sturges’ screwball classics from Paramount’s 1940s roster, you’ll have to look for the DVDs or Blu-rays released by Universal or the Criterion Collection.

For its first 50 years, Universal was primarily a mini-major dependent on serials and genre pictures—cranking out Deanna Durbin musicals and Abbott & Costello comedies alongside its monster and sci-fi flicks. But its successful series of richly envisioned melodramas directed by Douglas Sirk and produced by Ross Hunter in the 1950s could have easily been included in its classics-friendly anniversary slate for 2012. Dismissed initially as dewy soapers by critics of the day, box office smashes such as Magnificent Obsession (1954) and All That Heaven Allows (1955) have re-emerged in the decades since as skillful examples of how a smart, technically astute director with an ironist’s eye can subvert surface storytelling through composition, color, music, and mise-en-scéne. Sirk, whose great theme was the way American society imprisons souls as much as it frees them, now stands as the epitome of a studio director giving audiences and the higher-ups what they wanted—beautiful people acting out tortured romances—yet pleasing his artistic vision with aesthetic choices that enhanced some ideas and subtly underscored others.

Though the business of Hollywood studios is vastly different now, the history of Universal and Paramount is replete with brilliant directors plying their craft, which is why their centennials are a fitting time to celebrate those filmmakers, both in the officially restored Blu-ray releases and the broader roster of directors who helped give these two studios their identity.