BY JENNIFER PENDLETON

All photos courtesy Getty Images

BRIAN'S SONG (1971): (Left to right) Billy Dee

BRIAN'S SONG (1971): (Left to right) Billy Dee

Williams, Shelley Fabares and director Buzz Kulik DUEL (1971): Dennis Weaver in the first film directed

DUEL (1971): Dennis Weaver in the first film directed

by Steven Spielberg. THAT CERTAIN SUMMER (1972): (Left to right) Martin

THAT CERTAIN SUMMER (1972): (Left to right) Martin

Sheen, Director Lamont Johnson and Hal Holbrook. ELEANOR AND FRANKLIN (1976): Daniel Petrie (left),

ELEANOR AND FRANKLIN (1976): Daniel Petrie (left),

directing Jane Alexander (right) as the famous first lady.Television has been called a lot of things during its half century of existence, with "vast wasteland" and "idiot box" being two of the milder insults tossed its way. So it's hardly surprising that movies made expressly for the small screen rarely receive the acclaim of theatrical films. Critics often dismiss made-for-television movies as cheap entertainment, easily forgotten, disposable. Sometimes, the movies deserve it (as do many features); but often, these films are showcases of directorial skill and craft.

Over the years, movies for TV have stirred controversy, exposed social issues and told compelling stories. How many other films have had the impact of Brian's Song (1971, ABC), The Day After (1983, ABC), The Burning Bed (1984, NBC) or An Early Frost (1985, NBC)? At their best, made-for-television movies represent major achievements in filmmaking.

The men and women who direct these movies usually don't collect the accolades of their colleagues in features. There are no names above the title, nor is James Lipton rushing to book them on Inside the Actors Studio. But they're dedicated artists who deliver the goods under extreme time and budgetary constraints. "Some of our movies are great and some are not. But when they're great, the director deserves some credit instead of never being mentioned," says veteran director Mike Robe, whose many credits include With Intent to Kill (1984) and While I Was Gone (2004). "It's not as if the movie directed itself, there's a vision behind it."

The great accomplishments in television movies over the past 40 years could never have happened without the vision of dedicated directors. Like their counterparts in features, these filmmakers are responsible for giving cinematic voice to the story. It is their leadership that unifies the entire production and makes it work.

"We have passion for the story," says director Roger Young, who won a DGA award for the civil rights film Murder in Mississippi in 1991. "If you follow a director making a television movie around for even a couple of hours on a set, you'll see every decision they make is being driven by that passion."

So as the Directors Guild prepares to celebrate in 2006 four decades of original movies made for television, it's a timely opportunity to take a closer look at the origins and history of the medium and the directors who helped define it with the high quality of their work.

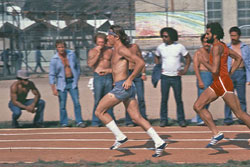

THE JERICHO MILE (1979): Peter Strauss starred in

THE JERICHO MILE (1979): Peter Strauss starred in

Michael Mann's film shot in Folsom Prison. THE DAY AFTER (1984):Nicholas Meyer's film about

THE DAY AFTER (1984):Nicholas Meyer's film about

the aftereffects of a nuclear bomb in Kansas. THE BURNING BED (1984): Farrah Fawcett set her

THE BURNING BED (1984): Farrah Fawcett set her

husband on fire in Robert Greenwald's film. SOMETHING ABOUT AMELIA (1984): Roxanna Zal and

SOMETHING ABOUT AMELIA (1984): Roxanna Zal and

Ted Danson in Randa Haines' incest drama.IN THE BEGINNING

For baby boomers who grew up in front of the flickering box, it's hard to remember a time before there were made-for-television movies. Their precursors were the great anthology series of the 1950s, programs such as Playhouse 90 and other golden age standard bearers, which primarily broadcast adaptations of plays. This is where major directors like Sidney Lumet, George Roy Hill and John Frankenheimer got their start. The first bona fide made-for-television film came in 1964. Times were changing and movies for television would reflect those changes.

Oddly enough, the first film made expressly for television didn't air on television. It was a thriller based on an Ernest Hemingway short story, The Killers, directed by Don Siegel, featuring a fading actor with a then-unforeseen destiny, Ronald Reagan. The powers that be found the finished product too violent for America's living rooms, so it was released in theaters to critical acclaim. The distinction of the first made-for-television movie to air went to See How they Run, an NBC chase saga about three kids pursued by hired killers directed by David Lowell Rich.

But the action in made-for-television movies didn't ramp up until NBC started working with MCA Universal Studios to make original two-hour world premiere movies. By the late 1960s, the two parties had struck a deal to create 100 films.

ABC's groundbreaking Movie of the Week also shook up television. Hollywood was skeptical of the then-struggling network's plan to churn out 25 90-minute films each year, budgeted at $350,000 to $450,000 with 10-11 day shoots.

The network felt otherwise, according to Gerald Isenberg, a former ABC movie executive and part of the team led by a young programmer named Barry Diller. "We believed we could create a marketplace. We believed the American audience wanted original movies. Of course, we were right beyond anybody's belief."

In a three-network world, with far less competition for audience attention than today, original movies gained traction. By the early 1970s, made-for-television movies had become pillars of network programming.

Brian's Song, directed by Buzz Kulik (1971, ABC), a true-life depiction of an interracial friendship in pro football ending in tragedy, became a cultural phenomenon. It was championed by President Nixon and, during a volatile time, was applauded for its depiction of race relations. And it still packs an emotional wallop today.

TV movies often tackled hot button social issues–racism, homosexuality, ageism, teen drug abuse, the war in Vietnam–and audiences responded in big numbers. "By the time we got into development for our second year, we were pretty cocky," recalls Isenberg. "If we looked at our ratings, and we had anything below a 40 or 45 share, we were aghast. Nobody could touch us."

The networks were emboldened, but still suffered through a few nervous moments. Lamont Johnson, who directed numerous celebrated made-for-television movies of that era, remembers receiving veiled warnings from network execs in 1970 about characters touching in My Sweet Charlie (NBC), a sensitive tale of an interracial romance. Patty Duke, who played an uneducated pregnant teenager in Texas, won an Emmy for her performance, as did the film's editing and screenplay. Johnson received the DGA Award that year for Best TV Director. Two years later, Johnson tackled the subject of homosexuality. In That Certain Summer (NBC), a teenage boy realizes that the relationship between his divorced father (Hal Holbrook) and a male friend (Martin Sheen) is more than friendship. Reviewing the film in the Los Angeles Times, Charles Champlin called it a film that "would do honor to any size screen," and praised it for "avoiding melodrama, moralizing or convenient resolutions." While directing the film, Johnson recalls getting "a marvelous memo, which I treasure to this day, from an executive who said there must be no physical contact between the men in this show–even lingering eye contact."

These movies helped shape popular perception. "At the time, it was the only way these issues got into the mainstream," observes Robert J. Thompson, professor of popular culture at Syracuse University. "They raised the consciousness of a lot of people."

Instructive as these movies could be, they wouldn't have attracted audiences had the storytelling, performance and production values not measured up. Successful made-for-television movies depend upon a confluence of creative elements–a well-written script, accomplished acting, skillful editing, and a director who can guide them–the same formula that dictates artistic success in any film.

AN EARLY FROST (1985): Gena Rowland as the mother

AN EARLY FROST (1985): Gena Rowland as the mother

of a young man dying from AIDS in John Erman's film. THE TUSKEGEE AIRMEN (1995): Lawrence Fishburne

THE TUSKEGEE AIRMEN (1995): Lawrence Fishburne

in Robert Markowitz's WWII film. GEORGE WALLACE (1997): John Frankenheimer (left)

GEORGE WALLACE (1997): John Frankenheimer (left)

directing Gary Sinese as the Southern segragationist. A LESSON BEFORE DYING (1999): Don Cheadle as a man

A LESSON BEFORE DYING (1999): Don Cheadle as a man

accused of killing a white store owner in Jon Sargent's drama.

The creative rush of directing on a tight schedule can be exhilarating and requires a special talent. "There is a discipline to making television movies," says Robert Markowitz, director of such television films as The Great Gatsby (2000) and The Tuskegee Airmen (1995). "To make them, you must have craft because you can't bring back a TV movie for a reshoot as you can in features."

As directors explored the potential of the genre and honed their craft, new possibilities developed. It was during the creative flowering of the made-for-television movie in the mid-'70s that the mini-series, or so-called novels for television, inspired by the BBC's tradition of dramatizing literary fare over multiple nights, came to the television networks. These complex stories often attracted major stars and delivered huge ratings. ABC's QB VII, directed by Tom Gries, led the way in 1974. Various noteworthy productions followed. Roots (1977, ABC), directed by David Greene, John Erman, Marvin J. Chomsky and Gilbert Moses, which became a Rosetta Stone for racial understanding in the U.S., undoubtedly had the most profound impact (see sidebar Nothing Mini About Mini Series).

It's worth noting that many feature directors established themselves in made-for-television movies and mini-series. Steven Spielberg shot his cult classic Duel (1971) for the small screen in 11 days during his fledgling days at Universal. The film already displayed his mastery of the visual depiction of emotions, and spurred a new wave of suspense films. Similarly, in 1979 a virtually unknown Michael Mann directed the grimly realistic The Jericho Mile on location at Folsom prison.

Aside from introducing new faces behind the camera, made-for-tv movies have long been a proving ground for new actors. This is exactly what happened to Markowitz on The Deadliest Season (CBS) in 1977. Newcomer Meryl Streep had been cast in a tiny part. "Meryl came in and she had maybe five or six lines. I immediately knew she was mind-blowing," Markowitz recalls. He convinced the writer/producer to tweak the script so key emotional scenes would take place between the lead (Michael Moriarity) and Streep. A year later, she won an Academy Award for best supporting actress in The Deer Hunter.

Throughout the 1980s, made-for-television movies continued their hot streak. Nearly 100 million Americans, almost half of all television sets, tuned in for The Day After (1983, ABC), a dramatization of the end of the world through the perspective of a small Midwestern town undergoing nuclear attack directed by Nicholas Meyer. The Burning Bed (1984, NBC), directed by Robert Greenwald, a true story of a battered wife tried for setting her abusive husband on fire as he slept, prompted many water cooler moments at workplaces around the country. Incest was exposed in Something About Amelia (1984), directed by Randa Haines, who elicited brilliant performances from Ted Danson and Glenn Close.

In the '90s, much of the made-for-television movie business shifted to pay cable. For these growing networks, original movies delivered respectable ratings, brand identity and a chance to attract top talent. For the directors, it has often been an opportunity to work on exciting material.

The late John Frankenheimer, whose career had a resurgence in the last decade of his life with acclaimed HBO films like George Wallace (1997) and Path to War (2002), once said in an interview that directors were "willing to make the financial sacrifices of working in television to get the chance to do superior material that they really believe in. I don't think that any of the movies I made as cable movies would have been made as feature films because the subject matter would have been too controversial."

Movies for television are attractive to cable networks because the financial commitment is not as substantial as for a series, and it's easy to tailor their content to match a targeted niche. "There's an audience that still wants to watch this particular kind of entertainment," says Trevor Walton, Lifetime Network's Senior Vice President of Original Movies.

This year, Lifetime is airing 18 originals, up by one-third from 2004, and plans to expand further. Tim Brooks, Lifetime's Executive Vice President of Research, estimates that basic cable networks, such as A&E, Disney Channel, ABC Family Channel, Hallmark, TNT, USA, and others, will pump out 100 or more original movies by the end of the year.

THE CRAFT

Although they come from varied backgrounds, the men and women who direct made-for-television movies have one thing in common–a commitment to the craft. In earlier times, there was a stigma about working in television if you already had a feature career; do too much television and you might find yourself slipping in an industry built on perceptions.

That's the way actor-turned-director Joe Sargent saw it in his early days in Hollywood, when the onetime student of Lee Strasberg and Stella Adler decided to re-invent himself as a made-for-television movie director.

"I immediately started turning down B-quality theatricals, for A-quality material, the movies for which I'm now identified," says Sargent, whose credits include the highly acclaimed Amber Waves (1980, ABC), the more recent Warm Springs (2005, HBO) and A Lesson Before Dying (1999, HBO). Now in his 44th year directing made-for-television movies, Sargent is widely recognized as a director's director by those in the field. "Joe does not make a shot list," said his longtime cinematographer Donald M. Morgan in an interview last year. "His magic is the spontaneous spark he can get out of the acting... Joe lets people settle in and works it until it's magic, and I think that's the secret to his success." Sargent has won numerous awards including the DGA's Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Movies for Television for Something the Lord Made (2004, HBO) and Most Outstanding Television Director in 1973 for The Marcus-Nelson Murders (CBS).

However, Sargent is just one of many renowned directors who have made their mark in the industry through an extensive body of award-winning work. Among the fine filmmakers in that group are: Frank Pierson (Conspiracy, 2001, HBO; Citizen Cohn, 1993, HBO; Soldier's Girl, 2003, Showtime); Dan Petrie, Sr. (My Name is Bill W., 1989; Eleanor and Franklin: The White House Years, 1977, ABC; Sybil, 1976, NBC); and former DGA President George Schaefer (Inherit the Wind, 1965, NBC; First, You Cry, 1979, CBS; and others he directed from 1960–1968 for the eponymously named George Schaefer's Showcase Theatre).

To be sure, there's more status in made-for-television movies today than in earlier eras, particularly as networks like HBO continue to attract A-list talent. One reason is that pay TV's looser content restrictions appeal to artists. As a result, expectations for made-for-television movie directions have grown, especially as cable features have started to mimic their theatrical counterparts with bigger budgets, higher wattage stars and special effects. In fact, it's not uncommon for a made-for cable film to open theatrically overseas.

THE BEACH BOYS: AN AMERICAN FAMILY (2000): Fred

THE BEACH BOYS: AN AMERICAN FAMILY (2000): Fred

Weller and Nick Stabile with director Jeff Bleckner. LIVE FROM BAGHDAD (2002):

Michael Keaton, Helena Bonham

LIVE FROM BAGHDAD (2002):

Michael Keaton, Helena Bonham

Carter, Lili Taylor and Joshua Leonard in Mick Jackson's film. THE ROMAN SPRING OF MRS.STONE (2003): Fred

THE ROMAN SPRING OF MRS.STONE (2003): Fred

Weller and Nick Stabile with director Jeff Bleckner. ANGELS IN AMERICA (2004): Emma Thompson played multiple

ANGELS IN AMERICA (2004): Emma Thompson played multiple

roles in Mike Nichols' epic staging of the Tony Kushner play. WARM SPRINGS (2005): Cynthia Nixon and

WARM SPRINGS (2005): Cynthia Nixon and

Kenneth Branagh in the Joe Sargent film.Still, the typical made-for-television movie shoots on a tight 18 to 25 day schedule and production budgets, always a fraction of feature films, haven't significantly increased in the past decade. At the top of the heap is HBO, with budgets reportedly in the $12 million to $15 million range. Broadcast network budgets hover between $3 million and $5 million and basic cable, $3 million and below.

So when these directors say "action," they mean it. Director Jeff Bleckner, who helmed The Beach Boys: An American Family (2000, ABC) and The Music Man (2003, ABC), tries to maximize efficiency through rigorous planning before he sets foot on set. "One of the big differences between a television movie director and a feature director is that you don't get to make choices in the editing room. You make your choices in prep," he says.

From Lithuania, on the set of his latest film, Have No Fear: The Life of John Paul II, for ABC, Bleckner says, "What I've learned is that you don't have control. You're trying to pilot a car that's going down a mountain very quickly, and you're just trying to steer it."

Of course the challenge lay in pulling it off with limited funds and a blindingly fast shooting schedule. "In the comparatively brief time we have to shoot these films, I try to take the small details of the story and make them appear in a way that is fresh," says Peter Levin, director of the Emmy-nominated Homeless to Harvard: The Liz Murray Story (2003, Lifetime) and Littlest Victims (1989, CBS). "I never get tired, and if I could shoot 365 days a year, I'd be happy."

"I see my job as getting everybody else inspired," says Katt Shea, whose TV films include Sanctuary (2001) and Sharing the Secret (2000). "If I can get the production designer to want to do the best work he's ever done in his life, I've done my job. If I can get the D.P. to do the best lighting he's every done in his life because he feels the freedom and energy to do it, and he puts the camera in a better place than I would think of because I'm worrying about 50 zillion other things, I feel like that's when I've done my job the best."

Whatever inherent problems exist in made-for-television movies, directors who chose to work in the genre see the advantages. It's a way to stay out of the endless meetings, rewrites and layers of approvals which theatrical film projects often undergo before receiving a green light. In comparison, television movies proceed relatively quickly. "Once something is going to go, it's going to go," observes director Mick Garris, who has brought several Steven King novels to the small screen, including the mini-series Desperation (2006, ABC) and The Shining (1997). "When they're talking to a director, it's because they're ready to make a film."

Television movies offer the opportunity to develop projects that the studios don't perceive as having the commercial punch to merit feature film investment. It's a chance to do serious material that wouldn't pass muster at a market test at a San Fernando Valley mall.

"What should be treasured about television movies is that it's the medium of intimate, character-driven pieces that aren't being made anymore by the big studios," says director Robert Allan Ackerman (The Reagans, 2003, Showtime), a New York theatre director who started making made-for-television movies 12 years ago. In 2003, Ackerman directed Tennessee Williams' The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone, the story of an aging, once glamorous woman who relies on paid escorts for social companionship, for Showtime. "I just can't imagine anybody in the feature world, even in the independent feature world, doing a Tennessee Williams piece today," Ackerman says. (Ironically, in 1961 it was a studio film, made by Warner Brothers with Warren Beatty playing one of the escorts.)

Some directors get hooked on television's potential to reach vast numbers and stir the national consciousness. British director Mick Jackson still recalls with pride how "nobody slept in Britain" the night his 1984 BBC made-for-television docu-drama Threads, a Cold War apocalyptic vision of the aftermath of nuclear war, aired. Jackson now shuttles between theatricals films and television, but says he's become disillusioned with features.

"Cinema seems to have gone more and more into a retreat from reality, into fantasy, '50s TV show re-hash, comic books, teenage boys' fantasies. Feel-good is the default mode," Jackson says.

In contrast, he's excited by the subjects television movies take on. Live from Baghdad, which Jackson directed for HBO, was originally intended to be a feature film. But after stalling in development, the tale of the news media in the first Gulf War found a home on the pay cable network in 2002. Making it work for the small screen required adjustments. The original script started off leisurely, but it was re-tooled to include an opening scene establishing the outbreak of war, a shot of a tank crushing a car. "Television has to command your attention immediately. It was a much bolder opening," says Jackson, who shot in Morocco and Culver City.

By sticking to quality and tackling serious, thought-provoking material unlikely to get much screen time at today's crowded multiplex, cable TV has taken on a greater role in carrying on the proudest traditions of the made-for-television movie. In 2005, Showtime aired Our Fathers, directed by Dan Curtis, an unflinching look at the sex scandals in the Catholic Church; Lifetime made Human Trafficking, directed by Christian Duguay, about young girls kidnapped into the sex trade; and in 2003, HBO produced Angels In America, directed by Mike Nichols, which tackled the AIDS epidemic and the culture of repression.

"That speaks to what television movies have always done," says Mike Robe. "They deal with controversial subjects, and take risks, when no one else is."