Adapted from Elia Kazan: A Biography by Richard Schickel

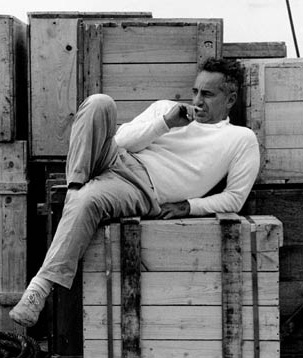

AT REST ON THE SET: Director Elia Kazan on the set of

AT REST ON THE SET: Director Elia Kazan on the set of

On The Waterfront. (© Costa/Manos/Magnum Photos)Elia Kazan was worried. He had now endured two theatrical flops (Flight Into Egypt, Camino Real) and three boxoffice failures (Panic in the Streets, Viva Zapata!, Man on the Tightrope) and the project he most cared about, now simply known as Waterfront, was suddenly in trouble.

It should not have been. Budd Schulberg's final first draft screenplay (which would go through many more rewrites) was excellent. "It's one of the three best I've ever had," Kazan told him. "And the other two were Death of a Salesman and A Streetcar Named Desire." This opinion was converted into a litany by Kazan: Salesman... Streetcar... Waterfront...

Some of the more intriguing matters in Schulberg's many drafts were the things that he and Kazan decided to omit. For example, Terry Malloy, in the early drafts, was not a longshoreman at all; he was an investigative reporter - "kind of a cynical newspaper reporter" in Schulberg's description - whose growing emotional involvement with the exploited workers mirrored his own journey to commitment to their cause. He was also, at first, an older man, divorced, with a grown daughter.

At some point, however, Schulberg conceived the idea that Terry should be younger and that he should be involved with a woman. "With my Hollywood background, I felt that we were going to tell a pretty tough story and that we needed a love story in the middle of it."

Kazan had believed, from the beginning, that Darryl Zanuck at Twentieth Century Fox was their most logical backer. To that point, Kazan had made most of his films for the studio under a long-term contract and had a long-standing relationship with Zanuck. Indeed, he obtained development money from him for the film. More importantly, he thought this was Zanuck's kind of picture.

But Kazan did not seem to notice that the kind of pictures he had been directing - intense, relatively small-scale, realistic dramas, shot in black-and-white - were becoming outmoded. It was odd. He, more than anyone else, had been responsible for bringing a new, much talked about style of acting to the screen, but he was apparently unaware of the forces that would, in a short time, render him virtually obsolete as a movie director.

According to Schulberg, Zanuck said he hated everything about the script. Kazan responded by stressing a comparison with The Grapes of Wrath - downtrodden folks struggling for a better life - but the producer was not buying. "Who's going to care about a lot of sweaty longshoremen?" he asked. The meeting broke up with recriminations. According to Schulberg, he and Kazan retreated to the office that had been assigned them and more or less trashed it, in the process of liberating a typewriter and toting it back with them to the Beverly Hills Hotel, where they discouragingly began yet another revision of their script.

THE SAME PAGE: Tenderness is what Kazan wanted

THE SAME PAGE: Tenderness is what Kazan wanted

from Brando's performance. (© Corbis)In Schulberg's account, Kazan began making calls to other studios, all of which passed on the project. "Goddamn it," he remembers the director saying, "I'm going to stick with this thing if I have to get a 16 millimeter camera and shoot it myself." There were very likely two meetings with Zanuck, during which substantive discussions of the proffered script were undertaken. There exists a transcript of Zanuck's remarks, in the course of which he apparently said, "if you come to me with this story in its present state and you say, 'I have got Marlon Brando for this picture' then it is a clear-cut and simple decision to make." But, of course, at this point, Brando was uninterested.

That this newly developing way of doing business did not kill Waterfront was something of a miracle - an oft-retold miracle. As it happened, Sam Spiegel was staying in a room down the hall from Kazan and Schulberg at the Beverly Hills Hotel. A sometime art director, he had produced mainly low-budget films – a notable exception had been John Huston's The African Queen - under the name S.P. Eagle, and was a legendary high roller. Schulberg knew him and one night approached him about producing Waterfront. The producer asked Schulberg to come to his room the next morning and read him the script.

Schulberg found the producer's door open, with Spiegel reposing in his bed. Not entirely certain Spiegel was fully awake, the writer began his recitation. It was occasionally interrupted by mumbles, mutterings and the occasional groan. But, at the end of the reading, Spiegel agreed to produce it. Neither Kazan nor Schulberg entirely trusted this sleepy word, but Spiegel followed through. His best relationship was at Columbia, where Harry Cohn still reigned, and he was able to set the picture up there on a very low budget.

It appears that Spiegel's largest contribution to On the Waterfront was Marlon Brando. The problem here was not the script he had not read, but his relationship with Kazan, which had deteriorated because of Kazan's HUAC testimony. In his autobiography, Brando represents himself as "conflicted" about the role. He said he knew some of the people "who had been deeply hurt. It was especially stupid because most of the people named were no longer Communists." Given these circumstances, a handshake deal to play Terry was instead struck with Frank Sinatra, a Hoboken native. His career as a movie crooner having faded, he had just scored a remarkable, ultimately Oscar-winning, comeback as Maggio, in From Here to Eternity, and was once again hot. Or at least hottish. But with him in the cast, Spiegel found that he could not get a big a budget for the film as he could with Brando starring. So the great Schnorrer (Brando's word) went to work on the actor, with, at first, indifferent results. In the meanwhile, it is said that Sinatra actually had a costume fitting for the role.

Sinatra technically had the Terry role, but Spiegel (and doubtless Kazan) still harbored hopes for Brando. At which point, Kazan ordered his friend Karl Malden, who had been helping him out with some casting on Waterfront, to direct a scene with Paul Newman - then still an Actors Studio tyro, two years from making his first movie. The stated idea was to show this piece to Spiegel as another alternative.

There was obviously a hidden agenda here. If Brando heard that a handsome young actor, cut from something like the same cloth, was in the running for a great role, it might move him to commitment. I don't know if this ploy influenced Brando. Malden recalls a late-night phone call from Brando's friend and agent, Jay Kantor, begging Malden to intercede with Brando to take the part. Malden says he refused to do so. He does, however, remember telling Kantor that this was the role of a lifetime and that the agent should do everything in his power to persuade Brando to do it. In the late summer or early fall, Brando signed for the part.

Ironically, getting Brando almost cost Malden his chance to play the priest, Father Barry, in Waterfront. For when Sinatra heard that he had lost the lead he angrily demanded to play the priest. As it happened, Spiegel somehow settled with Sinatra (in his autobiography Malden suggests Spiegel gave the singer a museum-quality painting as heart balm) and Malden kept his role.

Throughout the late summer and early fall of 1953, the wrangles over Waterfront continued, though it appears Spiegel realized his (and Kazan's) heart's desire - Brando - fairly early in this period. The rest of the players - almost all of them either Group Theatre or Actors Studio actors - fell fairly easily into place.

Eva Marie Saint was cast in the role of Edie Doyle. She thinks Kazan must have seen her in Horton Foote's play The Trip to Bountiful, which starred Lillian Gish, but also vividly remembers an improvisation she and Brando did for him. The director's instructions to her, as she recalled, were these: "This is a young man who is coming to visit your sister, your older sister. She is not home. And your mother and your father do not want you alone in the house with the opposite sex. So your action is to get him out, in fact, not to let him in the door."

Eva Marie Saint was a bit smitten with Brando.

Eva Marie Saint was a bit smitten with Brando.

(Photo courtesy of AMPAS)Brando's action was, naturally, the opposite - to somehow get flirtatiously in the room with the young woman, which he did. "The charm, the smile, he was beautiful then. He was just so attractive. And... we ended up dancing. I had an Ann Klein dress on, I remember. I had a belt and a full skirt and he took my skirt and he went like that [Saint made a whirling gesture and a wooshing noise]. All I know is that I ended up crying. Crying and laughing. I mean there was such an attraction there... That smile of his. I mean, I can see it my mind's eye to this day... I was not frightened. He didn't come in to rape the girl or anything. He wasn't mean. He was very tender and funny... And Kazan, in his genius, saw the chemistry there."

"Tender." That was the controlling impulse Kazan wanted for this movie, especially in Brando's performance. It characterizes his relationships with everyone that matters to him in the film - Edie, his brother, even his beloved pigeons. It is the quality that allows the film to transcend the harsh reality of its setting, the murderous corruption of its mobsters, the cowed passivity of its worker-victims. Without tenderness the movie would have been no more than an "interesting" twist on quite a basic gangster trope. Instead, it is, of course, one of the few truly indispensable American movies.

The film would become, for Kazan, one of the three that, late in life, he obsessively returned to (the others were A Face in the Crowd and America, America), running them again and again because he knew they were the ones on which rested what hopes of immortality he entertained. He said: "When I watch it... when he plays those scenes with her, I'm broken up. I break up. That one person should need so much from another person in the way of tenderness and all that. But we all do, don't we? We all marry or hopefully marry or hopefully hook up with some lady that's going to make us feel we're OK... we search for it and want it and crave it... and then sometimes it happens for a while. And something in that basic story is what stirs people. Not the social-political thing so much as the human element in it."

Taking nothing from Saint, Kazan attributes much of the film's heartbreaking power to Brando's work. "It seems to me however fine the script is and however fine the look of the picture, there's something in that performance that just tears your heart out. And I'm not sure that's inherent in the script."

Talking to me about Brando's work, forty years later, Kazan was volubly generous. "Externally, he's very gritty. I mean, he liked the streets. He liked those people, he liked the longshoremen. He used to lie around on the roof and talk with them. But that wasn't it. The thing was with Brando there is... both a toughness, an exterior roughness, and a tremendous desire for gentleness and tenderness. And the best scenes in the movie, from my point of view, are the scenes with Eva Saint, where he's asking her to understand him, where they're sitting in the café. He's great in those scenes. Why? Because he's a tough guy revealing a side of himself you didn't expect... the side of himself you didn't know existed... at the same time, he was a son of a bitch and a bad person. And a betrayer. Still, you wanted to help him. And she did, too. And that's what came off. He had that ambivalence to him... he's both hardy and indifferent and wants you to love him very much."

Kazan went on at much greater length, and with much greater subtlety, about Terry in a letter he wrote (but which we cannot be certain he sent) to Brando before he started shooting. He says that he "really wants to be photographing the kid's insides as much as exterior events," within the context of his "regaining his dignity or self-esteem." This regeneration, he says, "happens inside the man and has to be done by you so I can photograph it."

Kazan then makes a helpful comparison between Terry and Brando's Kowalski in Streetcar. Superficially they are similar - half-educated, half-literate men with a taste for settling disputes with their fists. But, he writes, they are very different. "Stanley is undivided. He is confident. He is on top. He has no self-doubts. He has no sex problems. He is not conceivably lonely." Terry has a similar swagger, "but his eyes betray him." He writes: "Marlon, this part is much closer to you and to myself, too." This was a shrewd stroke, for as we know, Brando detested Stanley. How much Kazan may have despised him is harder to say, since he hid his self-doubts - and his anger - much more cannily.

There is more in this vein. According to Kazan, Stanley is the "king of the dung heap. Terry is lonely, by himself, turned-in, mysterious... suspicious of all girls, all idealism. He doesn't want to be taken or fooled..." as opposed to Stanley who "is beyond self-doubt." He has "complete confidence in his cock as the great leveler, the equalizer."

Kazan is, I think, imputing too much to Terry, especially when he tries to delve into his sexuality. But it must also be said that there is powerful shyness, amounting almost to ineptitude, when he meets and is mysteriously, inarticulately, moved by Edie. Kazan is right to attempt to get Brando thinking about these ambivalent subtexts. They are the keys to Terry's character and, therefore, the key to the entire movie.

"He is a primitive," Kazan summed up. "He really can only half-read. He thinks too much, it gets painful and then he shakes it off, like a fighter might shake of a right cross. This combination of primitiveness and gentleness, of false savagery and self-doubt, of guilt and yet longing is the thing that makes the part fascinating to me." And, ultimately, to Brando.

From Kazan's point of view, this was a perfect shoot, a picture made in exactly the manner he had been aiming for since the beginning of his movie career. As he put it: "I was trained to work with people on location and I enjoyed it. I enjoyed the longshoremen... I liked them a lot. It was a great experience for me because I was on my feet all the time in the city and I think from that point of view it's as close as I ever came to making a film exactly the way I wanted."

In particular, he relished the punishing weather. "It was a cold goddamn winter. As we went along, it was more and more into the winter and more and more cold and rain and we never stopped shooting. We had these great barrels there and people would break down boxes and throw them into the [barrels]. We had hot boxes all the time." But you could not, of course, act and try to keep yourself warm over these fires, and that, in the end, gave the performers a certain look that Kazan wanted. "They didn't have this lovely flush of success that actors in Hollywood have... their dimpled, pink beautiful complexion. They were miserable-looking human beings and that includes Brando."

DOWN ON THE DOCKS: Kazan (right, in cap) loved being around the longshoreman.

DOWN ON THE DOCKS: Kazan (right, in cap) loved being around the longshoreman.

Brando (in plaid jacket) was on his best behavior but hated the cold.

(© Photo Columbia Pictures/Wesleyan University Cinema Archives)Brando was on his best behavior. He was the very model of good movie star manners. Saint would remember him frequently slipping his soon-to-be famous plaid jacket around her shivering shoulders. Kazan would remember having occasionally to drag him out of one of the rooms the production rented in a grim waterfront hotel to do his scenes, so reluctant was he to face the weather. But out he went - in good humor - with Schulberg remembering him saying, "You know, it's so fuckin' cold out here there's no way you c'n overact." And on the one occasion he began to do so - improvising with Steiger - Kazan put a quick stop to it: "Stop the shit, Buddy," was all he said.

That was pretty much what he did, directorially, on this picture - keep everyone underplaying in the naturalistic mode. Saint would recall that John Hamilton, the actor playing her father, went somewhat over the top in one highly emotional scene and she overheard Kazan whisper to him between takes, "just say the words, John," which quickly settled the actor. That sort of thing was pretty much his way on this film. He was always just sort of reassuringly there for his actors, as Saint recalled - "that great wonderful face of his right next to the camera... there was such empathy felt from this man."

He was particularly protective of this "thin, little, seemingly undernourished Catholic girl." Her first scene in the picture was one in which she comes up to the rooftop where Terry keeps his pigeons, to give him her dead brother's jacket, not yet knowing that it is Terry who betrayed him. The environment was, of course, strange to her, and Kazan told her to imagine that might be a ferocious animal in the pigeon coops - "it could be a bear, it could be a gorilla, it could be a lion." She remembers thinking, "My dear Gadge, you don't have to tell me to be frightened. I am so frightened - this is my first scene in the movie and all these people are watching."

But she soon settled into the rhythms of the location. Too much so, in Kazan's judgment. A friendly and rather uncomplicated person, Saint was soon genially chatting up the rest of the cast and crew. Until Kazan drew her aside and said: "Eva Marie, I want you to think of yourself as an hourglass. When you get up in the morning you've got so much energy and that's the sand going through, at what rate, so that you do not dissipate your energy. If I have a close-up of you, I can't put a card on the screen saying, 'Sorry, Eva Marie was just exhausted when she did this close-up.'"

But still, she had a certain natural exuberance, which occasionally willed out. She often wore, when the camera couldn't see them, heavy red tights under her prim navy blue skirts and she would occasionally do a little can-can, flashing the tights, on the docks between takes. And she found herself very drawn to Brando. Were she not recently, happily married (to Jeffrey Hayden, a producer), she implies she might have fallen for her gently seductive co-star. That, of course, did not happen.

If anyone tested Kazan's directorial patience, it was his producer. Spiegel would occasionally arrive at the location in his limousine, accompanied by one of his interchangeable young lovelies, wearing his camel-hair overcoat and stepping daintily over cables and detritus in his bespoke alligator shoes, to complain to all and sundry about Kazan running over schedule, costing him money he didn't have. On one such occasion - it was the night scene in which Terry discovers his murdered brother hanging from a meat hook - the director entirely lost it, screaming threats at Spiegel, threatening to quit.

But as the years went on both Kazan and Schulberg began to concede a certain amount of the film's success to Spiegel's compulsive attention to the script. In his autobiography, Kazan went so far as to say that without Spiegel's interventions the picture might have failed.

He was, indeed, more than usually modest about his contributions to the picture. I think he understood that there are certain - very rare - films that take on a life of their own, that seem, on the set, as they're being made, fated for greatness, and that wisdom consists of not intervening excessively in their progress. Later on, everyone can take credit for their foreordained success. Except, it must be said, in this case, no one ever has. In retrospect, everyone simply defers modestly to the phenomenon On the Waterfront became.

Take, for instance, the scene in the playground where Terry and Edie meet and shyly begin to acknowledge mutual attraction. In a rehearsal Saint dropped one of her gloves and Brando picked it up and started wriggling his large fingers into the glove. It was wonderful. What else, we wondered, might he like to wriggle into some small, tight Catholic part of Edie? Kazan just stood there - "the stupid director," in his later words, asking only that the actors duplicate the moment with the camera turning.

Or take what became On the Waterfront's signature scene, Brando and Steiger in the taxicab, with the former making his heartbreaking speech about his older brother not looking out for him, forcing him to take a dive in the bout which, had he won, "coulda" made him a "contender." (That immortal line, now part of the common American language was, incidentally, borrowed from Schulberg's father, who like Budd himself, was a boxing fanatic.) The scene kept bugging Brando, whose complaints went unheeded. Finally, Kazan and Schulberg settled down with him at lunch one day to get to the bottom of his problem. It seems the actor felt that his character would never have been so confessional with Charlie the Gent pointing a gun at him. He had a point, yet the gun was a necessary threat in the scene. So Kazan said, in effect, well, what if it's not aimed at you? What if it's present but pointing downward. That would work, Brando said. And it was done. Indeed, he brushes the weapon lightly away as the brothers talk.

A larger problem was the setting for their encounter. What was needed and expected for the scene was a real taxi and a full-scale set. What they had was a cab with its side cut open to accommodate the camera and no more than a blank wall behind it, which the cinematographer, the great Boris Kaufman, somehow made work with artful, quite minimal, lighting.

MAN TO MAN: Kazan takes no credit for the famous scene

MAN TO MAN: Kazan takes no credit for the famous scene

between Brando and Rod Steiger. "They made the scene,"

he said, "those two men." (Photo courtesy of AMPAS)There was worse to come. Brando deserted the scene - as far as one can tell, the only one shot on a soundstage - before it was finished. It was time for his sacred shrink appointment in Manhattan and he just up and left, as his contract permitted him to do. He was present, of course, for the two-shots and his close-ups, but left when it was time for Steiger's singles. Kazan filled in, reading Brando's words. The star's absence was a violation of common movie protocol, and Steiger never forgot it. He would go on about it the rest of his life. And surely aware that in the almost universal opinion of moviegoing mankind, the scene is regarded as unimprovable. Kazan always refused to take credit for the scene. "I didn't do any directing with it. You can believe it. It's true. I'm not a falsely modest man... They did it. They made the scene, those two men."

This sort of serendipity extended through the end of production, early 1954. Nor does it seem that there were any great problems in postproduction - though by this time Spiegel was increasingly nervous about the film and decided he needed a major composer to score it - one more, insuring name to adorn the posters. At the moment there was no bigger name than Leonard Bernstein, with two hit musicals, On the Town and Wonderful Town (the latter currently on Broadway) plus a number of more serious works to his credit; Spiegel invited him to screen Waterfront with Kazan and Brando also present. Bernstein was swept away by what he saw. "I heard music as I watched; that was enough," he later wrote.

He had never written a film score (and never would again) and so did not know the highly technical tricks of the trade. Basically, he sat down at a Moviola - no cue sheets, no tables that would allow him to convert footage counts to minutes and seconds, no assistant editor to run the machine. But he provided the perfect finishing touch to the film, for Bernstein was himself a romantic and his music plays to the film's most basic spirit, but without pandering to it. It is quite spare, but it knows when dissonance is called for and rises to sublimity at the climax when Brando, beaten to a point near death, must rise staggering to his feet and lead his men into work and away from Johnny Friendly's baleful influence.

When he had the music in, Kazan struck his answer print and showed it to Harry Cohn at his home, in his basement screening room. Cohn had reveled with some anonymous starlet before the screening and fell asleep, snoring, halfway through. The girl stayed awake, however, and told Kazan she liked what she saw. He decided not to risk a second running with Cohn and headed back to New York, choosing to read approval in those snores.

On the Waterfront opened in New York on July 28, 1954. The vast majority of the first reviews were favorable. On that morning, Kazan appeared at the Astor Theatre in Times Square to see if anyone was turning out for the first (11 a.m.) showing and was surprised to see something like one hundred customers in line at the boxoffice. He immediately guessed that his film was going to be a popular success.