BY ROB FELD

That's Entertainment: Miguel Arteta explains why The

That's Entertainment: Miguel Arteta explains why The

King of Comedy is "a perfect movie." (Credit: AMPAS)

"Anything that deals with embarrassment is interesting to me," Miguel Arteta says, getting ready to screen Martin Scorsese's

The King of Comedy. "I love it because it may be the most embarrassing movie ever made, in regard to the sheer amount of discomfort it elicits as you watch."

Arteta also revels in the cringe-worthy in his own films (Star Maps, Chuck & Buck and The Good Girl), as he runs his characters–usually eccentric, marginalized outsiders–through a gauntlet of humiliations to which they seem oblivious. "Subconsciously, Chuck & Buck was really influenced by The King of Comedy–the very clean, visual storytelling that I got from this movie," he says. As Arteta squirms in his seat watching Robert De Niro as Rupert Pupkin blindly humiliating himself, he seems to have the same visceral reaction he might draw from his own audience.

"In terms of the craft and storytelling, I think The King of Comedy is sort of a perfect movie," Arteta says. "One shot leads to the next in an amazing way and you can never guess what the next one will be. It's always inventive and completely to the point. The whole thing has such drive toward that ending."

Arteta has seen the film many times, and is now sitting in his New York apartment, having recently returned to the city after spending fifteen years in L.A. He first saw the film around 1986 in the film archives, while at Harvard. "I was already obsessed with making movies–I started in 1981 with a VHS camera and then a Super 8. Scorsese was a titan in my mind and I couldn't wait to see it. I could not have predicted such an original tale."

Though it has built a devoted following since it opened in 1983, The King of Comedy (from a script by Paul D. Zimmerman) was not a box office success. It's a strange movie with dark, twisted psyches running around what could otherwise be a straight screwball comedy, if it were directed differently. The film follows Pupkin, a wannabe stand-up comedian and autograph hound, who lives in his mother's basement. After helping America's top late night TV host Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis) escape Masha (Sandra Bernhardt), an obsessed fan, Pupkin becomes delusional in his conviction that Langford promised him a spot on his show. If Pupkin's character were not so poignantly portrayed and his pain so real, The King of Comedy would be a far easier film to categorize.

"I like melting and playing with tones," Arteta says. "I like movies that run a tricky spectrum of tones. This movie is a strange balancing act. It's supposed to be a comedy or a tragedy, but it evokes such earnest embarrassment. You recognize yourself in these characters in a way that is so uncomfortable. It's the most challenging movie that I can think of. Rupert idealizes Jerry but also just wants to use him to get somewhere. It feels like a very honest movie."

The film opens with an establishing video segment from The Jerry Langford Show, with Jerry giving the opening monologue, before cutting to Rupert approaching the waiting throngs of autograph seekers outside the stage door. He's wearing a striking red tie. "The red tie is a dead giveaway of his intensity," Arteta says. As Rupert pushes his way through the crowd, Arteta leans forward. "There, status, right away. He's saying, 'I'm not like you guys.' Look at his focus. It is the most committed performance that I have ever seen. You can't help but watch the movie and think that this is De Niro's real hidden self."

"Everything in Scorsese's movies is about understanding that game of status," Arteta explains. "Rupert is such a geeky guy, but he's doing the same thing. In my films my characters are very sensitive and have a very hard time with status, but they would all like to be better at it. The King of Comedy may be one of the greatest statements on status that we have."

And then we see a freeze frame, shot from inside Jerry's limo. Masha has hidden in the car and Jerry runs out fleeing. The shot freezes on her hands spread desperately against the window, with Rupert looking in at her, backlit by the cool light of flashbulbs. Ray Charles's raspy voice lays over, "I'm gonna love you like no one's loved you..." Arteta shakes his head. "That's unbelievable. You see Rupert trying to look in, like he doesn't belong, he's being left out. There's such a sadness and longing to be in a different place than where you are. It's interesting because Jerry's not even in the frame. Every obsession is not really about the object of the obsession but the people who are obsessed."

Arteta gets restless again at the awkwardness of Rupert's pitch in the back of Jerry's car. Jerry is annoyed and gives little response. "The silences are incredible," Arteta says. As Jerry leaves Rupert and walks up the steps to his building, Arteta again notes the use of red, this time the carpet, and the status suggested by ascending the stairs. Rupert embarrassingly offers to take Jerry to lunch, closing with "You're a prince!" an interesting position in the hierarchy since Rupert considers himself The King.

"There's another reason why I love this movie," Arteta admits. "My producing partner and I went to Vegas when Jerry Lewis was doing stand-up. Like Rupert, we hung out in the back by the trashcans until he came out in his tuxedo. We had with us a book he had written, The Total Filmmaker. He got really teary-eyed that we respected the book so much. This was before I had made any movies. He called us later from his boat in San Diego and invited us down. He talked to us for hours and gave us a lot of inspiration. Last year I was able to repay the favor by presenting The Nutty Professor at the DGA's Under the Influence series. I forgot to say that I love this movie because I'm like Rupert."

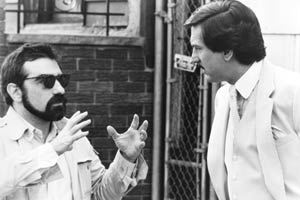

Royalty: Martin Scorsese directs Robert De Niro in The King of

Royalty: Martin Scorsese directs Robert De Niro in The King of

Comedy. (© 1982 Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corp.)Next, we find Jerry rattling around his cavernous apartment, populated only by sterile rooms, television monitors and a tiny, fluff-ball-of-a-dog with a red bow. "Scorsese is so smart," Arteta notes. "The movie is not told entirely from Rupert's point of view. You're spending time alone with Jerry here. From a storytelling perspective, there's just enough of everyone on their own." Jerry flips a channel. "You see his sadness. All the monitors; the paranoia. The little dog really makes the scene so sad."

Later in the film, Rupert parks himself in the reception area of Langford's office, imagining that Jerry will emerge to talk to him about being on the show. This, of course, will not happen, but Rupert is content to wait it out. "I love how the film is shot–always very simply with one thing in the foreground and one in the background," Arteta says. "The composition of this shot is so incredible, where he's sitting against the pillar. It's totally symmetrical and very flat. It's an awkward place to be sitting, looking at the ceiling." Arteta cringes in anticipation, "He's going to mention that it's cork..." Rupert, this time in a light blue suit and yellow tie, proceeds to carefully examine the ceiling, asking the receptionist, "Is that cork?"

Arteta laughs. Rupert is finally given the brush-off. He's told by the condescending Ms. Long (Shelley Hack) that he should first make a tape of his performance. Scorsese then cuts to Rupert exiting the revolving door to the street, where Masha is staking out the building. "There's not a moment lost," Arteta marvels. "That's a great shot of her. Look at her outfit. She looks like Angus from AC/DC, like an English schoolboy. The level of anger is so fantastic."

Arteta says one of the elements that makes the film so difficult to categorize is Scorsese's willingness to blur the reality of the film, taking his audience into disquieting moments and visuals that may be more impressionistic than literal. One such moment is when Rupert retires to his mother's basement to record his standup routine. He has recreated the set of The Jerry Langford Show, replete with celebrity cardboard cutouts: Liza Minnelli sitting for an interview with Jerry, a studio audience, Jerry giving his monologue.

Rupert sits at his desk to record. "Look at all the tapes behind him," Arteta says. "Creating someone's living environment is really key, obviously. The cutouts and the red behind him, it's like an American flag inverted. It's subtle. You wouldn't think of it. The set is very elaborate and sort of saying, 'Who cares about believability?' Taking those kinds of risks is what makes a movie great; you can say, 'this is an appropriate time to be more expressive than what the reality of the film calls for.'"

As Rupert begins his routine, he steps before an expansive studio audience printed on the wall. He is boxed in by walls, floor and ceiling, all stark and barren surface. It couldn't be a real place, but isn't quite a delusion, either. "This may be the image that most represents the movie," Arteta says. "Getting love from all the paper cutouts of the audience. It's that artificial love that we're willing to go for in America. It's really insane. The image is kind of horrifying. Look!" he says as the camera pulls out to reveal Rupert's surreal box. "It's a trap. To want this artificial love is a trap. By the end of the shot, this is like a jail."

Rupert returns to the reception area, again refusing to leave until he sees Jerry. Rupert sits against his pillar, exchanging awkward glances with the receptionist, who has no idea what to do with him. "I love these kinds of moments, where nothing's happening, where people are just waiting and looking at each other," Arteta says. "We did this in The Good Girl, when Jennifer Aniston and Tim Blake Nelson are waiting in the doctor's office for John C. Reilly to take his fertility test."

As the security guard finally escorts Rupert out, the camera stays in the reception room, watching through the glass doors. "Scorsese's brilliant at finding a body gesture that says it all. The guy escorts him to the elevator and puts his hands up as if to say, 'Buddy, what can I do, what can you do?' You might think the body language is kind of big–if an actor suggested that to me I'd say no–but Scorsese has the ability to see that, in this moment of time, it's visual and it's good. The people who are good do this; they get the actors to physicalize themselves in a way that is outrageous but feels natural."

"These cuts are incredible," Arteta says, anticipating what's coming. Rupert has showed up unannounced at Jerry's country house and Jerry throws him out. "Cut right to the gun!" Arteta cues, as Rupert and Masha are now waiting in a car to kidnap Jerry. "The storytelling is so great. Jerry went over the line with him by tossing him out, so now he's going to kick it up. You know, there are not that many scenes in the movie. Most movies have over 100 sequences. I think this is way under that. It's very clean. In all great storytelling, what you don't see is almost more important that what you do see. Scorsese's saying to his audience, I know you understand these things.

In his fantasy life, Rupert Pupkin (DeNiro) and Jerry Lanford

In his fantasy life, Rupert Pupkin (DeNiro) and Jerry Lanford

(Lewis) yuk it up on Jerry's late night TV show in Scorsese's

The King of Comedy. (Credit: AMPAS)"I may have this playing in a video loop in my house when I get one," says Arteta, only half joking. He's talking about the love scene between Masha and Jerry, whose mouth she has taped shut. Masha approaches the camera through the virtual forest of candles she has assembled. "All the candles. I mean, look at that shot! Isn't that incredible?" Masha seductively peels the tape from Jerry's mouth and starts declaring her love.

"I love this shot too," Arteta says, as Jerry escapes just in time to watch Rupert doing his routine on The Jerry Langford Show on a television in the window of an appliance store. "Jerry watching with all the TVs. His sheer anger. Look at that. Great acting. There's nothing missing in this film."

Having finally made it on television, Rupert allows himself to be led away by the FBI. "It's so great how we never go back to anything else after the arrest, it just comes to this montage of voices," Arteta says, again marveling at the film's economy and respect for its audience. "I hope that the movie, in years to come, gains steam and becomes a real classic. I think it will, as the culture of celebrity keeps ballooning insanely out of control. It is like reality TV. Rupert is forcing himself to become a star."