BY PETER RAINER

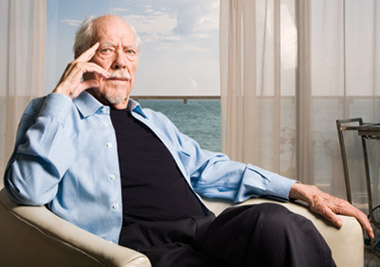

Photographed by Michael Grecco

I first met Robert Altman as a college student in the summer of 1973 during a weekend in Tarrytown, New York hosted by the film critic Judith Crist. It was part of a subscription series for local filmgoers. Altman spent much of the time schmoozing with the solidly suburban guests, a drink in one hand and sometimes, if the coast was clear, a joint in the other. The scene was very much like an Altman movie. The long weekend featured all of the Philip Marlowe films, everything from The Big Sleep to The Brasher Doubloon, and closed with the premiere of The Long Goodbye. The reception was predictably stupefied, but through it all Altman kept his cool. He knew what he had.

I met up again with Altman this August in his Manhattan office where he was cutting his latest film, A Prairie Home Companion, an adaptation of Garrison Keillor's radio show.

At 80, his looks have a fine-drawn, El Greco-like delicacy, but the old resiliency is still there. He has directed over 40 films and before making features he spent almost two decades doing industrials and episodic TV. His is one of the most improbable careers in the history of film: The director of upteen segments of Whirlybirds and Sugarfoot and Bonanza went on to make movies like McCabe and Mrs. Miller and Nashville that radicalized Hollywood with their art. His free-form storytelling, the buzz and hum of his soundtracks with their overlapping, sometimes intentionally inaudible dialogue, have given American movies a richer and more lyrical naturalism. He has managed to make movies his own way since the beginning, and a confounding number of them are classics.

When I spoke with Altman this time, the prickly competitiveness from the old days had burned away; in its place was almost a wistfulness at what his career has become.

PETER RAINER: You broke through as a major movie director in the late '60s and early '70s. Was that truly a Golden Age for American film?

ROBERT ALTMAN: I think so. Unfortunately. But I didn't think so at the time.

Q: When I look back at the movies from that era, even many of the best, they indulge in camera techniques, like rack focus and freeze frames, that are rarely employed today. From a strictly stylistic standpoint, the old-fashioned studio-era pictures often hold up better. Do you think that certain film techniques can become outdated?

A: The older pictures stayed more to the form and so they're more accessible in some ways. In the late '60s and early '70s I used to get all kinds of shit because I had the zoom lens going all the time. Now it's very commonplace.

Q: Suppose somebody came to you now and said, 'We want you to do the new Batman'?

A: Well, I could talk myself into that. But if they wanted me to just make another franchise film, I wouldn't know where to start.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I'm editing A Prairie Home Companion. I shot it in St. Paul in hi-def for about $7 million in about four weeks. It's a variety show, really. The first scene I shot with Lily Tomlin and Meryl Streep and Lindsay Lohan was the first day's shooting. We did a scene, two cameras. They entered a dressing room and improvised for almost 20 minutes. And then we'd do it again. And again. Things would change a lot. There were lots of mirrors on the set and the cameras were moving so I knew I didn't have any editing problems. If you start to shoot a picture where you're going to have to edit gracefully, you've got to be a little more careful because a lot of your options are taken away from you. But when you're doing it in this manner, I can go and make what is a bad cut and it's acceptable because it's in a series of bad cuts.

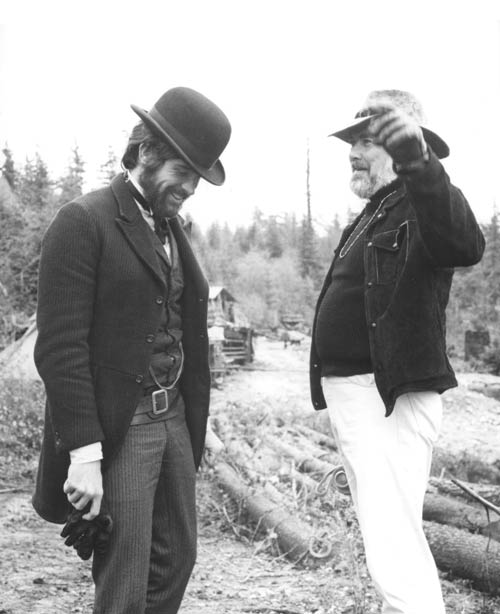

McCabe And Mrs. Miller (1971), starring Warren Beatty as a two-bit

McCabe And Mrs. Miller (1971), starring Warren Beatty as a two-bit

entrepreneur who opens a whorehouse in a fledgling mining town,

was Altman's version of How the West Was Won. (© AMPAS)

Q: Who else is in the film?

A: We had Kevin Kline, Woody Harrelson, John C. Reilly, Tommy Lee Jones, Virginia Madsen. Linsday Lohan, my god. The police had to come out. And of course she wouldn't stay in St. Paul. She had to be over in the big hotel in Minneapolis so that the paparazzi can get to her. All these actors are working for scale. They have to.

Q: That's because they want to work with you.

A: I've been turned down by these same people a lot, too. Something about the Garrison Keillor material compels them. I don't know what the picture will be. It's not like anything I've ever seen. The conceit is that it's the last broadcast of the radio show. This corporation comes in and, with the religious right, shuts it down. Sells the theatre for a parking lot. I tried not to put too much of myself into it and stayed instead with Garrison's sensibilities because he's a bit of a genius.

Q: Your late colleague Tommy Thompson once said that your movies were like an extension of your lifestyle.

A: When you make movies, there is a connection to your life, to the people you surround yourself with. It's a full experience. The movies you make are like little sculptures of what's around you.

Q: One of my favorite films of yours is The Long Goodbye. I love the way it was shot.

A: That film is still at the top of my list. I just never let the camera stop moving. I did the same thing on Gosford Park and on Prairie Home Companion, too. It was moving just for the sake of movement. I've been thinking a lot lately about Three Women and how slow and leisurely those camera moves were. We'd spend hours on them.

Q: What rubs you the wrong way about a stationery camera?

A: Maybe it's my own lack of confidence in where to put the camera.

Q: Why do you think The Long Goodbye holds up so well?

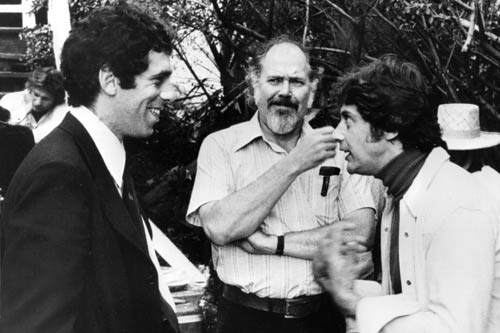

A: I can't figure it out. We made it just at the end of that weird era in the '70s when everything–the hippies, the cultural buzzwords–was extreme. Elliott Gould as Philip Marlowe looked like he was from the '40s in his black suit and tie. Everything he saw he couldn't believe. I called him Rip Van Marlowe.

Q: He is like so many of your heroes–a man out of time, an outsider on the inside. I think that movie crystallized your whole way of feeling.

A: I've done a bit of the same thing in Prairie Home Companion, where Kevin Kline plays Guy Noir, private eye. Like Elliott, he's 20 years too late. And Kevin is very good at that. I like taking actors out of other time warps and putting them in the present.

Q: You like to continually move the camera but you also like using multiple cameras.

A: I started shooting with two cameras a long time ago. McCabe and Mrs. Miller was shot with two cameras. It was efficient. We were getting away from the idea that once you lit a scene you couldn't move the camera. If you moved the camera, you had to move the light. If you moved the camera just this much you'd fuck it up. I said, 'I can't deal with that.' Suppose you come into a scene and you see a guy sitting at a desk. The audience knows the camera is on him alone. That's the only thing you're seeing. But suppose the camera is coming through the office and out of the corner of your eye you see somebody at their desk do something and you get sucked into that? That appeals to me more than the setup. Unless the setup is very specific and I'm using it as part of the storytelling.

Q: So many movies these days tell you exactly how to feel.

A: I don't think we give the audience enough credit. If you have to spell everything out for them, you've taken away their sense of discovery. My tendency is not to lead the audience. You see so many films where the camera or the editing takes you right to the person that is relevant in a scene. The audience doesn't get to make that choice. And of course, the industry now has gotten down to the 14-year-old male level.

Q: But you've never made a movie for the 14-year-old male audience. How is it different now?

A: At least I kidded myself into thinking I had a certain group of people who kind of got what I was doing.

Q: I think that's still true.

A: DVD has saved a lot of my work by making it accessible. I can give you a DVD right now of every film I've ever made. That couldn't have happened 20 years ago when most of my films were disintegrating. DVD saved all those pictures.

Q: Do you look at your old movies a lot?

A: I will if I have virgin eyes to look at them. The other night at two in the morning I looked at Prêt-a-Porter and I liked it.

Q: You sound surprised.

A: It was such a slapped-together piece of work.

Q: Is it possible to see your own movies with virgin eyes?

A: Through somebody else's I can. If you said to me, 'I never saw Streamers,' I could sit and look at the whole thing with you.

Elliott Gould (left), with Altman (center) and Mark Rydell, was the

Elliott Gould (left), with Altman (center) and Mark Rydell, was the

strangest of all Philip Marlowes in The Long Goodbye (1973).

(© AMPAS)

Q: Everyone is concerned now that the movie business is nosediving. Maybe this is a positive sign that audiences want better movies?

A: I think it is. Other than the last couple of Marty Scorsese pictures, what were the films you really looked forward to? Memento was a very interesting film. I enjoyed the puzzle of that.

Q: You mentioned storytelling earlier. I think the whole idea of story has broken down in American movies because producers do whatever they have to do to make a movie as marketable as possible and you end up with a research-based pastiche that often doesn't make a whole lot of sense.

A: You end up with something you've already seen. That's what comes out of all those research surveys.

Q: You rarely see cleanly told stories anymore. And yet the irony here is that you rejiggered the whole idea of neatly structured storytelling in the movies.

A: (Laughs) Yeah, I got what I wanted.

Q: What's the difference between what you're doing and the disarray we've been complaining about?

A: I can't tell you because I don't know what they're doing and I certainly don't know what I'm doing.

Q: I know you like Ingmar Bergman, who are some of the other directors you admire?

A: I always thought John Huston's films were right on the nose.

Q: What directors have influenced you?

A: I don't know their names, but when I'd see their pictures I'd say 'I want to be sure and never do that.' They are not the people you want to emulate.

Q: What do you like about shooting in hi-def?

A: I think it's terrific unless you're going to shoot some big outdoor epic with lots of sky. Prairie Home Companion was shot inside the Fitzgerald Theater in St. Paul. You could walk in and not know you were on a movie set because you didn't see any lights. I don't have to worry about how much film I shoot. I can take three cameras and turn 'em all on in the morning and turn 'em off at night. You don't have to wait for dailies to see how it looks. Dailies used to be such a big thing for me. We would shoot and the next day we'd sit down with the same group of people and run the movie. You don't do that anymore, not when you shoot in hi-def. You have too much footage to show and you've already seen it, because when you shoot it, that's what you get.

Q: Do you miss showing dailies?

A: It's just an element of the process that's disappeared. I used to be such an advocate of dailies that I would take a picture out on location just to get people out of their hometown so they'd have nothing to do at night except come to my dailies. And it worked. You had constant camaraderie. I wanted everyone to have the same enthusiasm. I remember being at a film conference in Montreal with Stephen Frears and he said, 'Oh, I don't look at dailies.' I was shocked. Through the years I've come to believe he's not doing anything wrong.

Q: Your sets have always been known for being very communal and open. You haven't turned into Otto Preminger have you?

A: Oh, no. That part of your personality pretty much remains the same. Harmony is very important to me.

Q: Some directors think disharmony on the set is a good thing because it fosters creative tension.

A: It might work for them but it would never work for me. Discord just destroys me.

Making a Point: Altman's directorial style of free-form storytelling and

Making a Point: Altman's directorial style of free-form storytelling and

buzzing soundtrack reached its height in Nashville (1975). (©AMPAS)

Q: You've been able to make the movies you want to make even though, excepting MASH, you've never had a smash hit. How do you account for this?

A: Persistence. Persistence. I've convinced myself that I've always made the movie I wanted to make. There's not any of them I would change although certainly there have been things that have not been successful.

Q: Why doesn't persistence work for everybody else?

A: I've had trouble getting films made. Ragtime is something I really wanted to do. I liked the whole philosophy of it. It really hurt me to get bumped from that picture.

Q: David Lean got bumped from The Bounty by the same guy, Dino De Laurentiis.

A: The studios eat you up. I see people now who are unemployable because if they don't have a hit, they're discarded. I've been eclectic in my taste and the kinds of things that I do. I've made more musicals than the Arthur Freed unit at MGM. People don't think of me that way. Nashville was a musical. Each one of the songs told you something about character.

Q: Do you think there's a connection between music and movie making? Editors are always the first to say it's a musical medium.

A: You do set up a tempo with the audience. My dance film The Company was almost abstract. That was a documentary, really. We used all the real people and just put them in a situation. We created our own reality.

Q: Is it scary to work so intuitively on the set?

A: It's scary just being out there.

Q: At the opposite extreme, you toiled for a decade in episodic TV.

A: You had to do it fast. That was the big exercise there. I'd be doing Whirlybirds or one of those things. Two and a half days. Wednesday at noon you finished and you started another one after lunch. Mostly you're imitating something you've already seen.

Q: At yet another extreme, you've also done many theatrical adaptations. In a way–I'm thinking particularly of Secret Honor and Come Back to the Five and Dime Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean–they're some of your most cinematic achievements.

A: I spent four or five years in the '80s almost exclusively putting the fourth wall in. I mean, I didn't even have a script, I'd just use the play. I don't care too much about screenplays now. I care about getting the actors to feel that they can just do something and then just photograph it.

Q: Actors seem to love working with you.

A: A lot of that comes from longevity. I'm older than all of them. They imbue me with foresight that doesn't really exist. But actors are remarkable people. They just amaze me. It's not so much what they do but that they do. They show up and have these wardrobe sessions and you don't have to do much more than say, 'Ok, here's the space.' And then you fill it and turn the camera on.

Altman, with Emily Watson, kept his camera roaming through

Altman, with Emily Watson, kept his camera roaming through

the upstairs and downstairs of an English country house

in Gosford Park (2001). © USA Films

Q: What was it like to work with Meryl Streep in your new movie?

A: She just brings 25 percent more. She doesn't need a director. Her performance could be hurt by a director.

Q: It seems to me that acting today, in general, is better. Often the only thing I go to the movies for now is to see a performance.

A: I think that's true but I also find there's a lot more overacting. By overacting I mean emoting.

Q: Any examples?

A: [laughs] Oh no, that's a big trap.

Q: It's often the stuff that wins awards.

A: Of course it is.

Q: What do you think of Daniel Day-Lewis?

A:

My Left Foot. Wasn't that something? I would not have had any idea how to do that.

Q: Really? Why is that?

A: I just accept the fact that if I'd gotten on the set and Day-Lewis started doing those things, I'd say, 'Oh, that's what it is.'

Q: But doing something that's difficult for you to understand is often what attracts you to a project, right?

A: It has more relevance to me.

Q: Do you regret never working with Brando?

A: Not really. I don't think I would have been of any value to Brando or vice versa. I could have done On the Waterfront but I don't think I could have maintained Kazan's intensity. Intensity is what he did.

Q: I thought Tim Roth was extraordinary in your Van Gogh movie Vincent and Theo, which was about your lifelong theme of the artist in conflict with the marketplace. Do you feel simpatico with Van Gogh? I notice you still have both ears.

A: No, no. He was truly mad. Van Gogh was just obsessed with what he did. His mother burned two trunks of canvasses when he died. Burned them without looking at them.

Q: Do you think it's possible to demystify art?

A: No, you would only be further mystifying it. There's something unexplained about great art. Once you've created art you've done it and whether it's recognized or not is another issue. You do what you do and you hope that people will say, 'Oh, you're the greatest director in the world.' And you start buying into it. But the big doubt is always there because you never believed it in the first place.

Host Garrison Keillor with Meryl Streep and Lindsay Lohan singing

Host Garrison Keillor with Meryl Streep and Lindsay Lohan singing

in a scene from Altman's latest film, A Prairie Home Companion,

an adaptation of Keillor's radio show. (© Noir Productions, Inc.)

Q: It's always difficult to talk about art in the movies because there's been so little of it, and yet, there are films that are unquestionably works of art.

A: I describe myself as an artist. That's what I do.

Q: Why an artist and not, say, an artisan?

A: [smiles] Because it's a better compliment.

Q: Back around the time of Short Cuts you said in an interview that you had another six or seven pictures left in you. So here we are thirteen years later and you've done eight pictures since then and counting. What did you do wrong?

A: I've made more than 40 films and upteen miles of television and theater and opera and all kinds of stuff. I've had a great life. But I'm more perplexed than ever about what to do. I'm a little afraid because I don't have any plans, I don't have a great thing that I want to make. I don't know what story anybody is going to be interested in that they haven't already seen. I just know that I won't spend my time doing something I've seen before. If I find that I'm imitating myself I'm gonna worry. But on the other hand, I think, well, why the fuck should I worry?