DGA Secretary-Treasurer Gil Cates (right), with cinematographer John Simmons (center) discussing Collected Stories

"I believe that films are the personal statement of their makers. Whether the motivation behind it is artistic or commercial, I still think that somehow it's infused with the fears and joys of its maker," said multiple DGA- and Academy Award-nominated director Norman Jewison.

"The challenge of protecting the director's vision goes to the heart of the Guild's existence," said DGA President Michael Apted. "Can we, or any creative guild, justify enforcing rules that members agree to follow without, at the same time, trampling on individual artistic freedoms?"

Protection of the director's creative rights is a guiding principle of the Directors Guild, and for very good reasons. Since its inception in 1936, when a dozen prominent and powerful directors met in secret to first organize, protecting the creative rights of the individual director has been the goal on the long collective bargaining road that led to what DGA members benefit from today.

Yet it wasn't until the 1978 contract negotiations that studios agreed that there would be only one director assigned to direct a motion picture at any given time. (Article 7-208 of the Basic Agreement)

Director Elliot Silverstein, chair of the 1978 Creative Rights Negotiating Committee, recalled that "Our concern was that the use of more than one director (and if two why not three or four, etc.?) would lead to the producer becoming an über director and the director(s) becoming messengers. We did not want the Guild's members to be involved in a 'piece goods' profession, blurring individual vision, authority and credit."

As reported in the March/April 1978 issue of Action magazine, the forerunner of DGA Magazine, "The 'one director to a film' provision, new to the 1978 agreement, is aimed at the burgeoning insistence of stars and producers that they receive co-director credit."

But the ideal of a "single director to a film" can be traced back even further. It was perhaps most eloquently expressed by Frank Capra, who, when working for former head of Columbia Pictures Harry Cohn, became convinced that this was the only way for a director to work. In Dialogue on Film, A Series of Seminars With Master Filmmakers: Frank Capra, 1979, a documentary film by the American Film Institute, Capra said, "I believed one man should make the film, and I believed the director should be that man. I just couldn't accept art from a committee. I can only accept art as an extension of the individual."

The reasoning behind a single director to a film also contains very practical business logic. A single director has proven to be the most efficient way to guide a film during production.

"A single director is an organizational imperative," DGA Secretary-Treasurer and Western Directors Council member Gil Cates explained. "A film is a complex form involving the integration of many elements. It's a composite from many people — the writer, the actor, the director of photography. I'm sure that what is going on in the world at the time is also thrown in as part of the composite. So I'm not saying the vision has to be generated by one person, but, the best way to have that integration be successful is to have it articulated by a single person."

It is for this reason that the director is often likened to the captain of a ship. And the principle is that there should be one authoritative voice to whom the hundreds of actors and craftspeople turn to for answers and direction from pre-production forward.

Director Norman Jewison coaches Denzel Washington in The Hurricane.

Production companies do not want more than one director on a film. Many producers and agents realize the immense difficulty in having more than one person call the shots.

For instance, former DGA President Robert Wise, in the book Robert Wise on His Films, talked about how producer Harold Mirisch reluctantly approached him about sharing his directing credit on West Side Story with Jerome Robbins. Robbins had developed the concept, choreographed and directed onstage this successful Broadway musical, but he had never directed a feature film. Wise thought that for the film to be equally successful, Robbins had to be in charge of the choreography. But Mirisch told him that unless he agreed to let Robbins co-direct with him, Robbins would not allow himself to be involved in the production. When Wise asked why they just didn't hire Robbins to direct, Mirisch replied that the project was far too complicated and expensive for a first-time director.

After some soul searching on his part, Wise finally agreed to co-direct with Robbins and was determined to make the arrangement work with Robbins directing the musical numbers and Wise the rest. "[But] we were getting behind schedule more and more and the company was getting very upset about this," Wise said. "We were pushing as much as we could, but they became convinced midway through that the co-directing situation was slowing things up. They finally insisted that Jerry go off the picture. It was a very uncomfortable, emotional, and difficult time for everybody, and certainly for Jerry."

Another valuable function of the "one director" rule is to ensure that the same kind of confusion that exists today on screenwriting and producing credits (who did what when?) does not become the fate of the directing credit.

For comparison, in the October 20, 2003 issue of The New Yorker, writer Tad Friend asks the question, "How many writers does it take to make a movie?" and goes on to detail the complex Writers Guild of America credit arbitration process. Using director Ang Lee's version of The Hulk as an example, Friend reported that "arbitrators had to digest 15 screenplays filled with easily conflated Hulks who all swatted military helicopters from the sky, as well as five sets of additional revisions and reams of 'source material.' (The Incredible Hulk comic books)." He further reported that "the majority of arbitrations result in 2-to-1 verdicts and sometimes all three arbiters disagree wildly."

On the producer side of the table, in January 2000, then Producers Guild President Thom Mount appeared on CNN Financial Network and spoke about the problem of too many producer credits, announcing the formation of a Producers Credit Board. "Credit inflation, of course, has become a joke," Mount said. "I'm always surprised that it's not a standard litany in every Jay Leno monologue. It is deeply silly to have everyone in the world sharing a producer credit who has no sense of how to make a film or doesn't do any work ... We hope there's some serious embarrassment factor out there for the cousin, the husband, the manager, the masseuse who feels entitled to a producer's credit."

It was precisely this type of credit confusion that the DGA managed to avoid by having the 1978 agreement specifically state that there would be only one director to a project. Over the last few decades, the single director to a film rule has protected directors from having the will of someone else, be it a producer, writer, actor or another, from imposing themselves on the director's role.

There were exceptions built into the single-director clause of the 1978 agreement — there could be more than one director for different segments of a multi-storied or multi-lingual film (e.g., New York Stories and Tora! Tora! Tora!), for different segments of a multi-part closed-end television series (e.g., Roots or Band of Brothers), assignment of a second unit director or any especially skilled director (e.g., underwater or aerial work) and for a "bona fide team."

Since the 1978 contract negotiation, the Western Directors Council (WDC) has reviewed all requests for waivers recognizing bona fide teams and the other rare exceptions to the rule.

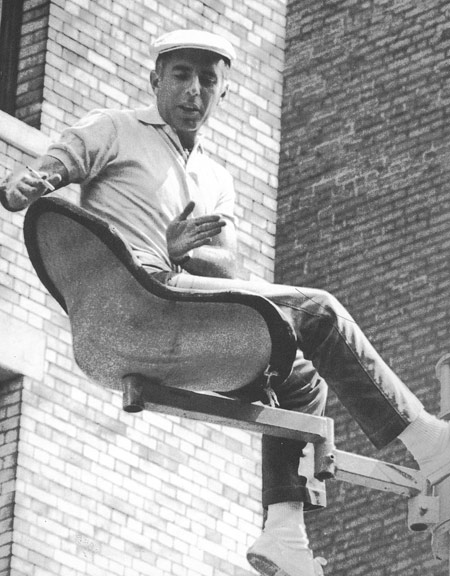

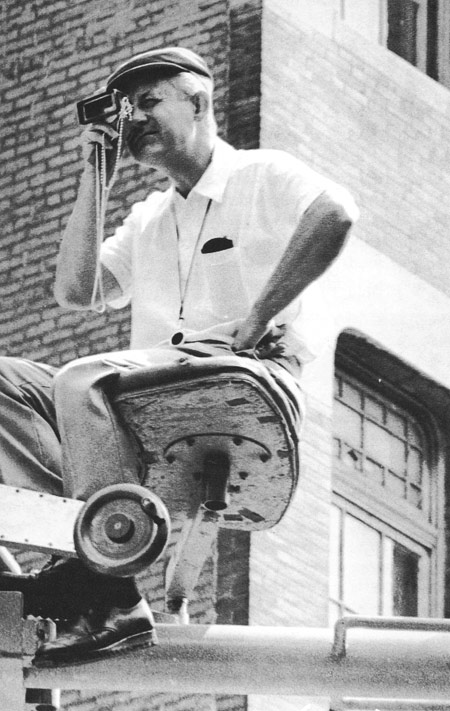

(Top) Director Jerome Robbins and (below) director Robert Wise on the set of West Side Story

There has been a substantial increase in co-directing waiver requests to the WDC. There were 15 requests (10 granted) between 1979 and 1989; 19 requests (11 granted) from 1990 to 1999. However, in the 39-month period since the new millennium there have been 22 requests for co-directing waivers of which 12 waivers were granted.

This sharp increase in requests has raised concerns about their effect on the integrity of the directing credit. And the WDC spends a great deal of time considering if these potential co-directing teams meet the standard of being a "bona fide team."

What is a bona fide team? The WDC has historically defined it as two or more people who have directed previously. They are directors who learned how to direct together, by actually doing it, and have, therefore, demonstrated that they perform the director's duties as if they were actually one director.

This may seem something of a paradox. How can two people direct their first film together if the DGA won't admit them as a team? Some of those who have are the Hughes Brothers (who co-directed music videos), the Wachowski Brothers (who had co-directed a feature film) and the Coen Brothers (who did not seek a co-directing waiver until their recently released remake of The Ladykillers). The WDC could also accept substantial co-directing experience in documentaries, commercials or other areas where it is permitted.

There is no doubt that directing is a creative, artistic enterprise. Some wonder, "If I am a filmmaker, why can't I just do what I want?"

"We live in an imperfect world where our freedom of expression and leadership are under constant siege from all kinds of powerful influences," Apted said. "The Guild has to be alert to these influences, some of which lurk in the shadowy corners of our business. I'm convinced we all have to sacrifice a piece of our individual freedoms to work within a set of standards and practices that protect the community of directors. Our only real strength in an increasingly tough world is our unity."

The argument is often raised in hearings that the people seeking a co-directing waiver have worked together for years as a writing team. But past writing-team experience is not a major factor for the WDC in assessing whether the applicants are a bona fide directing team. "Directing is very different from writing," Jewison said. "Decisions have to be made quickly and efficiently and there are a lot of people involved, sometimes in very strenuous and dangerous situations. It's a totally different occupation from writing. For the director, the meter is running so there is a tremendous amount of stress."

Directors Anthony Russo (left) and Joe Russo flank William H. Macy and Sam Rockwell on location for Welcome to Collinwood

Still, those unfamiliar with the craft of directing continue to argue that because they had written scripts together, they could direct together. Though Joe and Anthony Russo had written their low-budget independent films together, it was the fact that they had directed both the non-Guild feature length film Pieces and the short The Kiss together, as well as interviews with the brothers, that resulted in the WDC granting them a waiver to co-direct Welcome to Collinwood.

Anthony Russo explained that he found a significant difference between writing together and directing together. "Of course you have to write in a timely manner," Russo said, "but when you're writing, you very rarely have an experience where you have to make a major decision very quickly, and then the decision is unchangeable. You must make those decisions often when you're directing, not when you're writing.

"That puts a lot of pressure of the team collaboration," he added. "How you work out of those moments, when there's a whole lot riding on something, may boil down to be just a gut reaction. This may tie into why several co-directing teams are siblings. We grew up in a very tight-knit family where we depended on each other. Where we have that level of trust where you'll really defer to somebody else's gut reaction in that moment, even if you don't quite see it in that particular moment as well. That's a very difficult thing to do. It's significantly different from writing together."

Several of the waivers that have been granted by the WDC have indeed been to siblings. However, it is important to stress that being brothers or sisters does not automatically guarantee that a DGA co-directing waiver will be granted. While the biological connection may be a factor in their ability to work together and trust one another, it is the question of whether or not they have actually directed before, and did they prove they could do it as a team. The WDC also considers whether their past directing experience was of a significant length and did they learn the craft of directing together so that they really are inextricably linked as a team.

Some potential teams have also wondered why the role of the director couldn't be divided up to each member of the team's specialty. For instance, one director could work with the actors and the other could concentrate solely on the camera.

"In that situation, the spirit of making a film is bifurcated," Cates said. "What it says is, 'OK, there's going to be one voice speaking for the actor, and another voice speaking for the camera.' The best interpretation of music is made by a single conductor. The best painting is made by a single painter. And I think the best film is made by a single artist. There are exceptions to that, but they are rare. Occasionally you find two people who work together in a way that makes it almost impossible for them to work separately. But the business of dividing up the director's labor so that one talks to the actor, one talks to the cameraman is terrible."

Must a director concern him or herself with every element of the filmmaking process? Jewison explained: "It's essential. The director should know something about acting, writing, movement, dance, music, photography, the use of light and cinematography, editing, the juxtaposition of one frame to another. That's why directors usually develop through their career and seem to get a little better as they get older simply because they're applying all of this knowledge. Films are essentially a collaborative meeting of artists. It is a collaboration, totally. But every collaboration, especially when it becomes highly specialized, needs a direction in which to move and that's why you have a director."

It is that overall responsibility for all the elements of the film which ensures the unique position of the director. And while other guilds attempt to minimize the confusion over who is actually doing what on a film or television program, the DGA and the Western Directors Council have been operating for several decades under a clear mandate: protect the principle of one director to a film.

"This is not to say that we haven't made mistakes, and this is truly not to say that we won't make mistakes," Cates added. "We're not perfect, but we're in the service of an ideal, and the ideal, I think, is perfect."