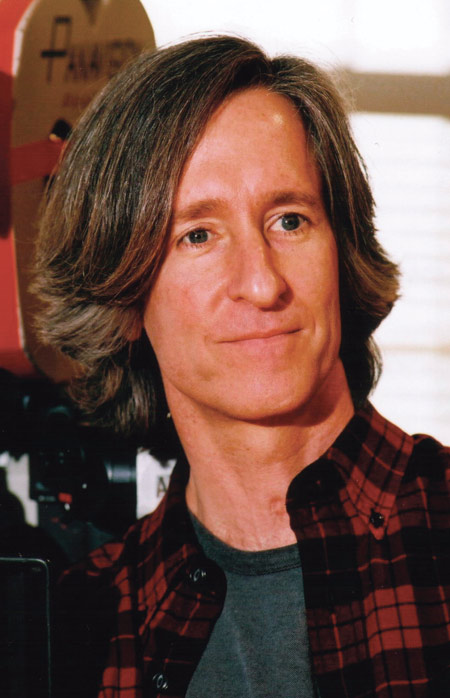

Director Rod Holcomb (left) with actress Mary Helgenberger on the set of Thanks of a Grateful Nation

This year will mark the 40th birthday of the Movie of the Week (MOW) and, not surprisingly, the event will prompt something of a midlife crisis. Having slogged through four decades of life, the MOW suffered its setbacks. But just as its career seemed to totter, the genre has gathered itself and seems poised for a creative revival.

The minuses for the MOW are well known. The level of production has fallen steadily over the last decade and shows no sign of a significant upturn. At the broadcast networks, television movies have become an endangered species, replaced by shows featuring bikini-clad young women diving into tubs filled with piranhas.

The positives, however, are just as real. Those productions making it to the screen — mostly on cable networks — have never been more vibrant or arresting, and these films suggest that the current crop of television directors may be reshaping the way people think about films made for the small screen.

This latter trend was demonstrated clearly by a number of notable productions over the past year. Mike Nichols' Angels in America — winner of the DGA Award for Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Movies for Television — and others represent the kind of risk-taking efforts that were rarely seen a decade ago and, some industry veterans believe, will constitute the leading edge of television movies in the future.

Whether these attention-grabbing movies will stir industry executives to increase production remains to be seen. But clearly they represent a break from the past and suggest there are new opportunities to make television movies that are both compelling and personal.

"You can give the cable companies all the credit for this," says Jane Anderson, DGA Award nominee for Normal. "If it was left to the networks, television movies would be long dead. HBO, Showtime and Turner are making it an exciting time because they give filmmakers a chance to do offbeat and experimental work. The cable companies don't have to worry about opening wide on the weekend, so they are in a position to take risks. It's just a miracle to me."

(Top) Director Jane Anderson on the set of Normal (below) Director Mick Garris on the set of Steve Martini's The Judge

Rod Holcomb, DGA Award nominee for The Pentagon Papers, largely agrees. "A decade ago we were stuck in that disease-of-the-week mode that marked a kind of low point," he says. "The movies were shot in Canada in two or three locations, and they all started to look the same. I find there's more of an adventuresome spirit now, and directors have more freedom to put their own stamp on the film."

In some recent instances, in fact, it has been the director who created the concept and written the script. That's what Jane Anderson did with Normal.

"Normal began as a play, and it was running at the Geffen Playhouse," Anderson says. "[HBO Films President] Colin Callender and [HBO Sr. Vice President, Development & Production] Keri Putnam came to see it and liked it. In about a week, they said, 'OK, let's do it.' It was stunningly simple."

An HBO release such as Normal will never attract the kind of large audience that once was demanded of network television movies. A cable audience of 2 million viewers for a television movie is usually regarded as a success. In the old days, a network movie needed to attract upward of 50 million viewers to be considered a respectable hit.

Director Lamont Johnson

"This means, with cable, you can play a niche audience and that's an advantage in many ways," says Mick Garris, director of such television movies as The Stand, Stephen King's The Shining and the upcoming feature film Riding the Bullet. "It means you can pay attention to your particular audience and explore the nuances. You don't have to appeal to everybody."

In many ways, the cable movies made today constitute a throwback to the early days of the MOW. In those days, the networks saw television movies as an opportunity to offer more serious fare than that served up by the typical weekly series. The very first network movie to make its premiere on television, in fact, was See How They Run, a tense mobster drama that starred John Forsythe and was directed by David Lowell Rich.

Over the next decade or so, other television movies dealt with interracial love (My Sweet Charlie in 1970, directed by Lamont Johnson); grimy prison life (The Glass House in 1972, directed by Tom Gries and written by Truman Capote); and the problems faced by a gay father (That Certain Summer in 1972, also directed by Lamont Johnson).

In so doing, the MOW became known as the genre that explored the touch points of American culture. But it was not achieved easily or without conflict. Four-time DGA Movies for Television Award winner Lamont Johnson recalls that the networks often hesitated before approving projects involving controversial subjects. This was especially the case with My Sweet Charlie.