By Amy Dawes

By Amy Dawes

The day after The Hangover Part II opened, I downloaded a copy of it from the Internet on a site called The Pirate Bay. The film did record-breaking business in theaters; I witnessed some of that turnout firsthand when I went to Hollywood's ArcLight Cinemas on Memorial Day weekend to see Terrence Malick's The Tree of Life. Between Hangover II, Bridesmaids, and the Malick movie, the lobby that day was overflowing with a lively, psyched-up crowd, which would seem to signal halcyon days for the movie business. Except that I now own a watchable copy of The Hangover II—and didn't have to pay a cent for it.

I also streamed the latest Pirates of the Caribbean movie and found links for Thor, Kung Fu Panda 2, and Woody Allen's Midnight in Paris—all of which were in theaters that weekend. I kept trying to find Bridesmaids, and couldn't get it, but I'll try again later. So stay tuned.

Before last week, I'd never committed an act of online movie theft and didn't know how. I agreed to go where I had never gone before to do this story, which aims to reveal how relatively easy it is for even a novice with a minimum level of technical skill to engage in the practice of Internet theft, and how shockingly pervasive it has become.

Seeing it firsthand, what I found within just a few days is eye opening. There's a surging, seething universe of participants in this shadow enterprise. Titles are often available within days of their theatrical opening, and it's not just mainstream movies that are being boosted—you'll find indie titles like Winters' Bone, The Kids Are All Right, and even rarities like Howard Hawks' 1927 silent film Paid to Love. Advertisers as large as Sprint, AT&T, and Microsoft appear on these rogue sites. While the host sites and servers exist to make a buck, the content is uploaded by technically adept but largely unpaid contributors—but even they can now reap income from the practice via so-called "affiliate programs."

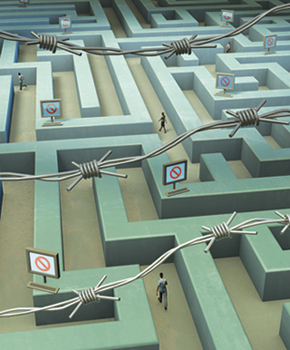

How simple does the current system make it for the viewer? "It's really pretty easy," I was told by the experienced practitioners I tapped for guidance. Well, not at first it wasn't. Let's say you take the easiest possible route, and Google a movie title such as Inception, along with words like "watch movie online free." Google will return a ton of links, and that's where the wild goose chase begins. Movie titles are bait, and every skanky site out there wants to capture traffic, so many a trap has been laid. Go to these sites, and most likely you'll not only not find Inception for free, you'll get hit with so many attacks, pop-ups, and come-ons that you'll be hard-pressed to remember what you're doing there. Aggressive attempts will be made to change your search engine and home page. Your anti-virus firewall will kick into action, and if you don't have one, God help you. Free iPads and pink laptops will be offered if only you'll enter your e-mail address. Not just Inception, but thousands of stolen titles will be dangled, if you just agree to be billed for "less than the price of four movie tickets" or some other vague proposition, details of which will not be provided until you have parted with your credit card information. You can spend hours banging around like this—hours of your life that you won't enjoy and that you'll never get back. Such is the way of this black market, where the lowered standards one displays by engaging in this criminal activity are returned in kind.

|

GLOSSARY OF TERMS

» AFFILIATE PROGRAMS:

A means by which cyberlockers offer financial incentives to those who post links to copyright-infringing content.

» BITTORRENT:

A peer-to-peer file sharing protocol (or digital message format) used for distributing large amounts of data, including video and music files. Examples: The Pirate Bay, Torrentz.

» CLIENT PROGRAMS:

Downloadable programs that interface with BitTorrent sites to manage uploads and downloads. Examples: Miro, Vuze, LimeWire, BitComet.

» CYBERLOCKER:

An online storage provider typically optimized for sharing large content files among many users who can download the files that others have uploaded. Examples: Megavideo, RapidShare, Megaupload.

» DOWNLOADING:

The permanent capture of multimedia files from a remote system to a local hard drive.

» PEER-TO-PEER:

Networked distribution in which the workload is partitioned (or shared) among peers who are both suppliers and consumers. Popularized by file-sharing systems such as Napster.

» ROGUE SITE:

A website set up for illicit purposes, such as spreading a virus or collecting information for spammers. In the realm of copyright protection, it is a site that may appear to be legitimate, but supports Internet theft or contains content that is being distributed illegally.

» STREAMING:

A "live" delivery method in which video is constantly received by and presented to an end user while being delivered by a streaming provider.

|

The better way, it turns out, is to wade in armed with the names of some destinations recommended by users in the know, and then go directly to these sites. You'll quickly encounter the first fork in the road: Do you propose to stream or download your pirated movies?

Streaming is the first route I took. It's the simplest and quickest avenue to illicit gratification, which is why the practice is spreading like kudzu, aided by the proliferation of free Wi-Fi locations and faster broadband connections.

Having grown discouraged on my own, I sought instruction from a dedicated practitioner who could afford to buy movie tickets but rarely does. "People talk in theaters," he explained when I arrived at his home. "Plus, most movies are so mediocre that I'd rather watch them this way, where I can do something else at the same time, or bail out fast if I lose interest."

We fired up my laptop PC, a recent model Toshiba netbook, a light portable designed for Internet access. My guide uses a Macbook, and says it doesn't make any difference. We typed in the name of one of his preferred portals, a so-called "linking site" that offers television shows as well as thousands of alphabetized movie titles to browse through.

Getting started wasn't completely painless—first I had to register, which required an e-mail address and a password. I didn't want to get loads of spam, so I set up a new account for free on Gmail that I would use for only this, and within a couple minutes I was hooked up. Once you choose the movies and film "channel," the ad-supported site offers an enormous list of titles.

We decided to look for Limitless, the Neil Burger thriller, which I'd missed in theaters, and there it was. I clicked on the title, then on a button labeled "play movie," and got introduced to the degrees of separation that make digital movie theft possible. The initial linking site, one is informed, "does not stream, host, communicate, or make available content of any kind." Instead, it offers links to videos, which are hosted from "a wide range of third-party sites." "We have no knowledge" the disclaimer goes on to say, "of whether content shown on such sites is or is not authorized by the content owner, as that is a matter between the host site and the content owner."

So that's how it works. The linking site goes on to say, "If you are the copyright owner of the video on the third-party site that this page links to and you have not authorized it for publication, then please report this link to us immediately for removal." It then offers a link to instructions on how to do this.

Meanwhile, in our pursuit of Limitless, we were redirected to a site called Megavideo, which I've learned is a cyberlocker (more on that later). Once there, we found that it offered a choice of either streaming or downloading the movie. We chose streaming, clicked on the play button, and the movie started. That's all there was to it. Our DSL connection delivered the goods. There was Bradley Cooper on the streets of New York, all scruffy and distracted-looking, before he takes the magic pill that sharpens his mind. The image quality wasn't bad—it wasn't great, but these things vary widely depending on who uploaded the movie and what standards were applied. Links are labeled with coded information such as BRRip (from a Blu-ray disc); DVD-Rip (from a DVD); and Cam, for a video shot with a camcorder from a theater screen (typically the lowest quality). The streaming player gives you options—you can go full screen, or to a 4:3 aspect ratio, and so on. There's a pause button too. Midway into this, I'm informed by my mentor that, based on his experience, the stream will pause about 54 minutes in, and we'll have to endure an intermission of about an hour while it buffers, and then the stream will resume. If we want to avoid this, we can pay for a membership, which will also eliminate pop-up ads and the like—but we didn't. So that was my introduction to streaming. We fired up his laptop too, and soon we were simultaneously watching Kenneth Branagh's Thor, which had opened in theaters just two weeks before.

My guide said he'd never paid a cent during the course of his considerable online movie watching, and also that he'd never downloaded a movie—all he did was stream, explaining, "I only want to watch them once and don't want them taking up space on my computer."

But downloading is a huge part of digital theft, so I set out to try that again on my own. This time I used Google Videos rather than Google, and from its "advance video search" function I specified I wanted to search for clips 20 minutes or longer—thus eliminating the trailers and interviews that comprise the bulk of links. But I still found that there was way too much to sift through for someone with my limited patience.

Another contact, who works in the visual effects side of the business, e-mailed me some tips. "It's really very simple. First what you need is a BitTorrent client, such as Vuze (Google search "Vuze" and it should pop up with a download link). This is a program that will allow you to download peer-to-peer files. Once that's installed, you just go to a BitTorrent website, such as The Pirate Bay or Torrentz, and type in what you want to find."

BitTorrent, it turns out, is a protocol (or code) for peer-to-peer sharing of large data files. It can be used to post a video of your cat doing something hilarious or a two-hour academic lecture aimed at the betterment of mankind, but it's also the basis for much of the music and movie uploading and downloading that comprises digital piracy. A BitTorrent "client" is a computer program that manages those downloads and uploads.

There are tons of these client programs, with names like LimeWire, BitComet, and uTorrent. As recommended, I tried Vuze first, but in my case it wasn't such a painless experience. I was hit with an exhausting series of other programs I was told I needed to also download, such as an Xvid Codec player, a Flash upgrade, and an iLivid download manager, and other things that required opening accounts and being pitched on upgrades for a price. Also, my computer was infiltrated with adware and the like. I mysteriously acquired a screensaver that played short funny videos that were punctuated by ads whenever I left the room. Vuze wasn't getting me anywhere, so I uninstalled it. At that point I was really frustrated. Many hours had slipped by, and I was beginning to think I was genetically incapable of stealing a movie.

he next morning I resolved to give it one more try. This time I went straight to The Pirate Bay, the well-established, ad-funded website based in Sweden that's one of the major BitTorrent players, and followed its instructions to download a client called Miro. Once that was set up, I learned I had to add The Pirate Bay and any other sources I wanted to access via a "subscribe" or "add sources" button within Miro, and it took me awhile to find that button and carry this out. But once I did—and then went back to The Pirate Bay from within Miro—I was presented with a search box. It soon became apparent that I'd made a breakthrough. When I typed in True Grit, I got back a bunch of links to the recent Coen brothers movie, with information about format (such as BRRip or DVD-Rip) and file size. I chose a modestly sized one, in hopes that it would download faster, clicked on download, and waited.

Meanwhile, pop-up ads were slithering up and down the sides of my screen, featuring barely legal girls such as Lola, who was barely wearing pink panties and a bra, and Nicky, who was busting out of a tank top. They were both making "friend requests" which I could confirm or ignore, but I knew they weren't sent to me from Facebook. Other ads, which kept getting between my cursor and what it wanted to do, hawked things from car insurance and video games to Groupons. It was like stumbling through a carnival on the way to the big tent, or navigating the tawdry Times Square of the 1980s in search of a theater playing a movie that, once it started, you could hope would take you away from all this.

Apparently, you can pay to upgrade to a membership level that lets you avoid this kind of thing, or at least sites of this kind say you can—who knows? But for the purposes of this experiment, I was operating only in the realm of what could be obtained for free.

My download of True Grit, from a link coded as DVDrip.Xvid-NYDIC, was coming from a third-party site called Scenetime. I could track its progress by way of an orange loading bar that slowly stretched across my screen to fill a slot. It took about an hour for the orange bar to reach its target. When it did, it was replaced by a little green go button. I clicked on it. After all I had been through, I have to say that what happened next seemed like magic.

The Paramount logo swirled across the screen, and then the movie began to unfurl, the images playing as smooth as silk. The picture quality was pristine, the audio was robust, and the movie, needless to say, was entrancing. At the outset of the movie, the following legend appeared onscreen: "The wicked flee when none pursueth." It was meant to refer to the movie's villain (Josh Brolin), and whether he would get away with killing the father of 14-year-old Mattie (Hailee Steinfeld). But I wondered if it might also apply to the content thieves who had delivered into my hands something I had no legal right to—a free, crisp, permanent copy of a movie that, as it happened, was then still a full week away from its DVD release date.

Of course, there are pursuers. All kinds of attempts are being made to foil or shut down digital theft of illegal content. Many have been reported on in this magazine, including my own story last fall about Operation In Our Sites, the Department of Justice sting that seized seven major pirate sites in a single day, and has since closed down many more.

In May, important new legislation was introduced in the Senate aimed at cutting off the flow of financial support from the U.S. to offshore rogue sites engaged in the theft of movies, TV shows, and music (as well as counterfeit hard goods like pharmaceuticals). Called the PROTECT IP Act (IP stands for intellectual property), it provides a means for copyright holders (typically studios and production companies) and the Department of Justice to take action to prevent search engines, payment processors, advertising networks, and Internet service providers from providing the transactions and support that make it possible for infringing sites to earn revenue outside the reach of U.S. law. (Many are based in foreign countries such as Russia, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden, and Colombia where they can operate with impunity.) The IP Act was passed unanimously out of the Senate Judiciary Committee and its next step will be to move to the Senate floor.

The bill is "aimed at starving these rogue sites by cutting off their access to income from the American public," explains Kathy Garmezy, Associate Executive Director for Government and International Affairs for the Directors Guild, which is actively campaigning to advance the legislation.

In June, the Senate Judiciary Committee also approved the Commercial Felony Streaming Act, which upgrades streaming for commercial gain from a misdemeanor offense to a felony, equivalent to peer-to-peer downloading. The DGA, as part of an industry-wide coalition, released a joint statement applauding the bill "for recognizing that digital content theft via streaming is just as illegal as digital content theft via downloading, and for leading the charge to apply the same criminal penalties to illegal streaming that already apply to illegal downloading."

"Many in our industry are working hard to create a business model in the face of all the changes the digital era has brought," says Garmezy. "However, no good business model can become a reality if it has to compete against millions of stolen copies that are ostensibly offered for free. A legitimate business model is one that compensates those who took the risk—whether financial or creative—in the first place. While illegal Internet distribution is still unchecked, we also have to be continually dealing with legislation and law enforcement issues."

Of course, the studios themselves (and the MPAA, acting on their behalf) devote significant resources to the battle. Warner Bros., for example, has an anti-piracy division that operates in the U.S., Europe, and Asia. It uses automated Web crawlers, among other methods, to track sites for content infringement. It also enforces a security protocol, including the use of watermarks, to protect its movies and games in the postproduction stages before their release, and forensic marks are used to protect content through distribution channels as well.

"We spend a lot of time and money securing our supply chain to make sure that our film and game content doesn't get stolen," says David Kaplan, Warner Bros.' senior vice president for worldwide anti-piracy operations. Most theft, he says, takes place after a movie hits screens but before it's available on DVD, or when a movie or TV show is available in one territory but not another. Kaplan notes that Warner Bros. takes a multi-pronged approach—enforcement, supply chain security, technology, and business intelligence—with the most aggressive tactics reserved for individuals and sites involved in the initial capturing and distributing of infringing content. These cases are often referred to criminal authorities.

As for the end users, the studio has learned to view them as potential customers. "Generally speaking, they are fans of our content who also consume it legitimately," says Kaplan. "So our main goal is to respond to the demand by providing access to legitimate content in a way that would deter them from piracy." For example, Warner Bros. has shortened the time before release for video on demand content in certain foreign markets. "We responded to foreign demand for the CW Network show The Vampire Diaries by releasing it early on iTunes in international markets shortly after broadcast in the U.S."

Kaplan's perspective on digital theft spans the last 15 years. "Right now developments are taking place so dramatically and quickly that you have to be nimble to be effective," he says. "When it comes to legislative efforts, we have tried to be flexible and 'future proof' new proposed legislation by anticipating how that piracy landscape will change."

Studios efforts also include contracting with companies that specialize in content protection and copyright enforcement. One such company, Peer Media Technologies, counts Paramount, Universal, Disney, Warner Bros., Lionsgate, and The Weinstein Company on its client list.

Much of Peer Media's activity centers on policing sites for links to infringing content and getting them taken down, says Harry Wan, the company's chief technical officer. It also engages in aggressive tactics such as "swarming" (posting files spliced with undesirable content) and "decoying" (posting fake links that prove to be empty after the user downloads them). "We deploy a variety of methods to try to make the experience as poor for the end user as possible," says Wan. These direct-action tactics also serve to set a trap for host sites, because if The Pirate Bay, for example, moves quickly to take down the fake links, as these sites typically do to protect their "brand" image for the user, the host site can no longer claim to be ignorant of the infringing content, which is a common defense.

In spite of these efforts, new players continue to enter the piracy game. The practice of linking to direct downloads from cyberlockers is a growing trend that offers a somewhat more reliable end user experience than BitTorrent, Wan says. That's because BitTorrent delivers content in piecemeal segments dispersed from seeders (uploaders) to leechers (downloaders). If not enough users are engaged in the process at any given time, it can slow or stall. It's akin to taking a shuttle home from the airport—it won't depart until enough passengers have boarded. A direct download from a single online storage provider (cyberlocker) avoids potential hang-ups.

Recently, cyberlockers such as Megavideo and FileSonic have increased their traffic by offering a financial incentive to people who post links. On FileSonic, for example, the so-called "affiliate program" pays $35 for every 1,000 downloads generated from a given link. "So unfortunately for the content owner, here's another group of people who are making money off their creative work," says Wan. "And it gives them an incentive to continually repost links after we take them down."

As for my own experience, after my breakthrough in capturing True Grit, I felt empowered—even somewhat ensnared by this illicit new thrill. That day was a blur of downloading. I learned I could browse freshly posted titles on sites like Realtorrentz, where a typical glimpse included Fast Five, The Fighter, HBO's Game of Thrones, 127 Hours, Rango, the Oscar foreign language nominee A Prophet, the Sundance Audience Award winner Happythankyou-

moreplease, and even the 1956 John Ford classic The Searchers.

"It's jolting to realize that people can access that creative work and exploit it without in any way compensating the people who made it," says David Yates, the British director of four Harry Potter films, including the two-part finale of the franchise, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. Deathly Hallows: Part 1 is ranked third among the most frequently stolen titles worldwide thus far in 2011 by Peer Media, with 2.5 million illegal downloads and counting (behind Inception and The Tourist).

"It's shocking and unfortunate that this is going on," says Yates. "I've seen how this kind of thing has decimated the music industry. And if movies become accessible as freely as music has, there won't be movies with this kind of complexity of scale anymore—it won't make economic sense to make them. What people don't realize is that they ultimately destroy the thing they're downloading."

And with that go thousands of jobs. "I've been very fortunate in that I've been rewarded," adds Yates, "but supporting me are the crews, the main unit, the second unit, the visual effects side, the 3-D conversion side. We have a whole infrastructure dependent on these larger movies for their livelihood. There's a whole industry that could be damaged or wiped out."

As for my own experiment, I eventually found Bridesmaids about two weeks after it opened, and successfully downloaded it. I soon had a mini-library of stolen film titles. I did encounter quite a few stalled downloads and fake links, though, which degraded the experience. And when I got around to watching The Hangover Part II, I found it was a camcorder version, poorly lit but watchable, in which, at one point, a woman with a ponytail leaves her seat and crosses in front of the theater screen, then returns a few minutes later. Allowances must be made. Still, for those who feel no compunction stealing other people's work, I'm sure there are ways to improve the experience.

But I wouldn't want to find out. It's a slippery slope that I choose to avoid. I live among the people who make movies and television for a living, or aspire to. My friends and colleagues are the ones who provide visual effects, titles, production supervision, casting, costumes, research, and the many other services production requires. If only the reality of Internet theft could become that tangible to everyone worldwide who considers watching movies and TV shows illegally to be a victimless crime. In any case, I'm deleting all my files and uninstalling my BitTorrent client. Then I'm going to browse the local listings and see what's playing on the big screen.