BY ANDREW KEEN

Illustrated by Heads of State

One of the Internet's greatest fallacies, its fishiest tale, is the idea of the "Long Tail." Popularized by Wired magazine editor-in-chief Chris Anderson, first in a 2004 magazine article and then in the bestselling 2006 book, The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More, it argues that the Internet is an ideal distribution platform for independent filmmakers, musicians, and writers struggling to compete against the financial might of mass media conglomerates. By providing online stores with infinite shelf space, Anderson, among others, contend that the Internet balances the playing field between the large movie studios and the independent filmmaker and guarantees that a rich and deep catalogue of indie artists is always available to consumers.

But Anderson's argument has a fatal flaw. He forgets about Internet theft—the online cesspool of illegal peer-to-peer networks and illegal streaming services that has already decimated the music business and is now doing potentially irreparable damage to the motion picture industry. And in the face of piracy, I'm afraid, the belief that all the value in the Internet economy can be located in its tail is, literally, turned on its head. Rather than a long tail, Internet theft's mass looting of the content industry is transforming the Internet into a fat-headed economy with everything on top—an increasingly unequal medium which discriminates against independent filmmakers and makes it harder, rather than easier, for them to make a living from today's digital economy.

So imagine the impact of Internet theft on the movie industry as being the exact reverse of the Long Tail. While Anderson's theory—and he is by no means the only one suggesting this—sees the Internet as having the most benefit to the small producer of content, online theft could actually hurt the independent filmmaker the most, while still having a serious economic impact on the revenues of both medium-budget ($30-60 million) and large studio movies. Rather than being the salvation of the independent and mid-budget director, the Internet may well signal their decline.

Even before the epidemic of Internet theft, the business of producing and distributing independent movies was notoriously tough. The margins are much thinner for indies than for large, big budget studio productions and, thus, the impact of piracy can be much more pronounced on the bottom line of smaller movies. So what is a very serious and damaging threat to the major studios can often be a matter of life and death for either a small-budget or even a mid-range film.

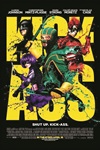

Besides, the difference in the impact of Internet theft on movies isn't proportional to the costs of the movie. So, for example, a big studio production such as Avatar, which cost around $500 million to make, has, according to the Bay Area-based tracking service BayTSP, been illegally downloaded on eDonkey and BitTorrent 13 million times, while a medium budget movie such as The Social Network, which cost $40 million to make has been downloaded 9 million times over the last six months. The superhero movie Kick-Ass, which cost around $30 million to make and collected $48 million at the domestic box office (that's only $24 million to the studio after the exhibitor's share), sold approximately 6.1 million tickets. Meanwhile, according to TorrentFreak, it was the second-most downloaded movie in 2010, with 11.4 million downloads worldwide. The comparison between Avatar and Kick-Ass is particularly instructive: the medium budget movie cost 15 percent of the big studio production, but suffered almost as many illegal downloads, crippling its chances to recoup its investment.

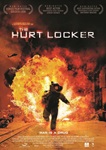

STOLEN PROPERTY: Many low- and mid-budget films, such as these, have had their

STOLEN PROPERTY: Many low- and mid-budget films, such as these, have had their

revenue cut into by extensive illegal downloads worldwide. (Credit: Everett)

Another instructive example is the critically acclaimed The Hurt Locker, which cost $15 million to produce and came in ninth on the TorrentFreak 2010 list with almost 7 million downloads. Its overall worldwide box office was a disappointing $49 million, despite winning a DGA Award and an Oscar for best picture and best director. Given the dramatic impact of Internet theft on this small budget indie, it's the difference between a profitable movie and breaking even, between financial success and failure.

And even modestly budgeted independent films that received Oscar nominations were subject to significant bursts of illegal downloading. According to the anti-piracy tracking firm Peer Media Technologies, Winter's Bone ($2 million budget, $11.4 million worldwide gross) was downloaded 329,227 times in just a three-week period from Feb. 12-March 7, 2011; and The Kids Are All Right ($4 million budget, $34.7 million gross) was downloaded 292,596 times in the same period. That represents serious revenue loss for films that can ill afford it.

For low budget independent films—which almost always play on many fewer screens than the larger, big budget productions—any missed revenue can represent the difference between a profitable and unprofitable movie. The disintegration of the DVD market is catastrophic for smaller movies which have historically relied on home video rather than theatrical business for an even greater percentage of their overall revenue—and thus their ability to recoup investments. Add to this already depressing story the literal disappearance of entire geographical DVD markets such as Spain because of endemic piracy and you have a perfect economic and cultural storm now confronting a young filmmaker trying to break into the industry.

Thieves don't, of course, discriminate between stealing Avatar and a smaller, more crafted motion picture made by a team of independent artists. A stolen movie is, to state the obvious, a stolen movie. In addition to a greater reliance on downstream revenue, what also distinguishes independent from big studio films are their radically unequal economic and political resources dedicated to fighting piracy. Whereas the major studios have entire teams of technical and legal experts dedicated to responding to illegal networks like The Pirate Bay and are members of powerful anti-piracy trade associations such as the MPAA, so the independent moviemaker has far fewer resources to fight the hydra-headed scourge of Internet theft. Indeed, independent filmmakers don't even have the resources to track the impact of piracy on their films, which means that fighting the widespread stealing of their product becomes even more speculative and arbitrary.

Good intelligence is critical to defeating Internet theft. Like any successful criminal network, online pirate organizations are purposefully opaque and protean. Thus their sophisticated technology requires careful and constant study if it is to be successfully fought and defeated. But while larger studios have built up an ongoing institutional knowledge base about complex networks like BitTorrent, independent moviemakers have neither the resources nor the technological expertise to even understand what they are fighting. The battle between the large criminal networks of file-sharers and fragmented and poorly informed independent moviemakers is, therefore, truly unequal—and there is only ever one winner—the thief.

Often the indie movie director is forced to confront the thief on his or her own, without the expensive resources of either a legal team or trade association. Penelope Spheeris, for example, the director of studio hits such as Wayne's World and the indie trilogy, The Decline of Western Civilization, Parts I, II, and III, who now chooses to work as an independent filmmaker, is forced to check auction sites like eBay every week to make sure that pirates aren't auctioning off illegal copies of her movies. It's a thankless task. Spheeris has been subjected to endless insults and even physical threats. In one instance, a young thief e-mailed Spheeris threatening to beat "the snot out of you." In another, when she was trying to protect a movie that hadn't been released on DVD but was being bootlegged and auctioned off on eBay, somebody anonymously e-mailed her: "Your majesty, Penelope Spheeris, release it or shut the fuck up about it."

Spheeris sees Internet theft as "the straw that breaks the camel's back" when it comes to the economics of independent moviemaking. It's "making it difficult for low-budget movies to be made," she told me in a recent interview. Impossible to defeat, yet massively time-consuming, Spheeris compares the struggle with online theft to be akin to "putting out a forest fire with one's bare feet." It's a full-time job tracking the Internet for pirates, she says, and yet—as a relatively low-budget independent filmmaker whose work typically costs around $3 million to make—Spheeris lacks the resources to effectively police the myriad thieves who are stealing her work on the Internet.

Ondi Timoner, the director of the acclaimed 2009 documentary We Live in Public, which won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, shares Spheeris' concern about the Sisyphean nature of fighting the pirates. Once a movie gets onto the file-sharing network BitTorrent, Timoner told me, pirated work is like a malignant cell that will inevitably grow. For all We Live in Public's critical success, Timoner still has what she called "a long way to go" before returning the $1 million that the movie cost. This failure to turn a profit on such a low budget movie, she explains, is threefold. First, the DVD market "isn't doing well"; second, revenue from legal online streaming services like Netflix is still small; and third, the cancer of piracy is seeing three new sites a day illegally ripping off her movie. She also cites what she angrily calls bad distributors as being a major reason why so many independent filmmakers are struggling to make a living in today's increasingly Internet-centric creative economy.

"What am I supposed to do to get the pirates?" Timoner pleads. "I'm so busy already writing, producing, directing, distributing."

Indie directors such as Penelope Spheeris (top) and Ondi Timoner (bottom)

Indie directors such as Penelope Spheeris (top) and Ondi Timoner (bottom)

lack the resources to be able to police the Internet for thieves themselves.

But even when independent filmmakers try to get the pirates, they often get lost in the labyrinthine ecosystem of piracy's grey online economy. Ellen Seidler is the co-director of the 2009 film And Then Came Lola, a low-budget spoof on Run Lola Run. Self-financed for around $250,000, the movie received critical acclaim and was screened in over 100 festivals worldwide. But DVD sales were disappointing, partially because the movie began to be illegally streamed by offshore networks that sold ads via marketing platforms such as Google's AdSense to profit from the pirated product. Having complained to some of these advertising companies that thieves were using their networks to monetize stolen content, Seidler found herself embroiled in Kafkaesque conversations about the legal rights of these illegal streaming sites to "free online speech."

"But it's not about free speech," Seidler told me, "it's about theft."

Timoner, Seidler, and Spheeris are all rightly concerned with the cult of free content that has permeated our culture. Many consumers have forgotten that their primary role in the entertainment economy is to pay for the content they are enjoying. "We have graduated kindergarten but have never grown up," Timoner told me, citing the example of a particularly naïve Norwegian fan who messaged her on the Internet, telling the director that it was "super cool" she had accessed We Live in Public for free on one of the illegal P2P networks.

Jason Reitman, the director of Up in the Air and Juno, had a very similar experience to Timoner at a film festival in 2008. It was the "scariest thing," he remembers. A college-aged kid came up to him and, having complimented the director on the "awesomeness" of Juno (which was, by the way, one of the top 10 most-stolen movies of 2008), boasted about having downloaded it from an illegal file-sharing site.

What Reitman found so disturbing was how at ease the college student appeared about stealing the movie. It's become socially acceptable to steal. That's why, he says, the music business "had its guts kicked in by piracy." And it's why, he believes, the independent movie business is now facing the same struggle for its very survival.

Reitman has a term for the type of motion picture facing extinction because of piracy. He calls them "tweeners"—the movies between the $10,000 YouTube home videos and the large-budget studio productions. Reitman sees the "tweener" as the lifeblood of the creative industry—producing movies as culturally significant and economically successful as Lost in Translation, American Beauty, and Pulp Fiction. It's these movies, he believes which "push cinema forward," producing the Sofia Coppolas and Quentin Tarantinos who then go on to make bigger budget and more lucrative movies.

Artists working in the film business are not the only ones dramatically affected by digital theft. In February of this year, Scott Turow, president of the Authors Guild, testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee, and noted that the policies which currently govern the digital age have created an environment that permits the growth of businesses that profit from stolen works. "One is tempted to call it a vast underground economy," he said, "but there's nothing underground about it: it operates in plain sight…. Money clearly suffuses the system, paying for countless servers, vast amounts of bandwidth, and specialized services that speed and cloak the transmission of stolen creative works. Excluded from this cash flow are the authors, musicians, songwriters, and publishers who invest in them."

In our increasingly "tail-less" digital economy, Reitman is rightly depressed about the future of the industry. Independent film has "always been fighting for its life," he says. But now, with the ubiquitous piracy of P2P networks and the rapidly growing problem of cyberlockers and rogue websites specializing in illegal streaming, as well as the social acceptance of online stealing, he doesn't know how we'll be able to watch quality movies in the future if nobody can afford to make them.

Reitman is correct. Not only is piracy making it harder to make money with independent movies, but it's also becoming more and more difficult to raise money to make the film in the first place. Veteran indie producer Cotty Chubb told me that the collapse of the DVD market, along with the epidemic of online theft, is having a significant impact on a studio's or investor's willingness to invest in independent movies. John Sloss, one of the most powerful and successful sales representatives and producers of independent movies, believes that the industry ignores piracy at its peril. Although Sloss blames much of the piracy infestation on the studio's unwillingness to allow Internet users to pay to watch movies when they first come out in theaters, he nonetheless has a "major concern" about the impact of illegal downloads and streaming on the industry.

So what to do? How can we ensure the survival of independent movies, which, as Reitman reminds us, are a critical component of our broader cultural vitality?

The DGA has worked for several years, in concert with its partners in the industry, to raise awareness of the need for more aggressive government legislation to counter the mass looting on the Internet. Congress is starting to listen. Last year, Congressional legislation entitled the Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeits Act (COICA) was introduced. COICA was designed to shut down illegal (so called "rogue") websites, which are profit-making digital stores that traffic in stolen films, TV programs, music, and everything from pharmaceuticals to airplane parts. Under this legislation, when an illegal site is identified by the Department of Justice, not only can it be shut down but the U.S. credit card companies, payment processors, and advertising placement agencies who patronize them would be informed and told to remove themselves accordingly—just as if a store the public frequented was caught operating an illegal practice. The goal of course is to break the stranglehold of these illegal entities—the very stranglehold that frustrated Seidler's fight against the unlawful distribution of And Then Came Lola.

Last year's bill had full bipartisan support, from its introduction by Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT), and Judiciary Committee Chairman and Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-UT) to its passage out of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Votes for the bill came from all 19 members of the Senate Judiciary Committee, from Republicans Lindsey Graham and John Cornyn to Democrats Amy Klobuchar, Charles Schumer, and Dick Durbin. It also had the broad support of the entertainment industry, the Newspaper Association of America, the Intellectual Property Committee of the National Association of Attorneys General, the AFL-CIO, the U.S Chamber of Commerce, and of numerous businesses such as Nike and Major League Baseball. This legislation will be re-introduced in the spring.

Powerful forces that build their business model on the availability of content they do not pay for will be aligned against this bill when it goes before Congress this year. Thus, education is also critical in the fight against online theft. The industry needs to be sure the public understands that those hurt are not just the tentpole movies; it needs to collectively publicize the Sisyphean struggle of directors like Spheeris and Seidler against criminal streaming, downloading, and copying. Illegal downloaders, most of whom are thoughtless rather than evil, need to understand the consequences of their action. The message should be very simple: File sharing is not only killing thoughtful movies, but it is also making it impossible for a new generation of talented filmmakers to emerge. The more you steal, consumers need to understand, the fewer Sofia Coppolas and Jason Reitmans there will be in the future.

The major studios and industry groups should also be willing to share their intelligence about pirate networks with independent moviemakers. As I've argued before, information is priceless in this struggle and the makers of indie movies are severely disabled by lack of intelligence about illegal file sharing and streaming networks. The more we can empower independent filmmakers with valuable information, the more we can help directors who would otherwise be entirely alone in their struggle against piracy.

For all its early promise about democratizing the opportunities for independent filmmakers, the Internet has actually done the reverse. The long-tail economy is actually the fat-headed economy. By mostly ignoring the piracy problem for the last 15 years, we've created the conditions for the destruction of high-quality, thoughtful filmmaking. This may be the most serious crisis in the industry's history. Collective action is essential. Anything less may eventually mark the demise of independent cinema in America.