BY ANN FARMER

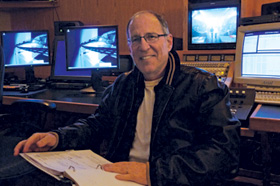

Director Eytan Keller relishes the live quality and unpreictability of the show.

Director Eytan Keller relishes the live quality and unpreictability of the show.

(All Photo Credits: Food Network)

Accidents sometimes happen while taping the Food Network's reality TV game show Iron Chef America. The chefs occasionally cut themselves. Appliances break. Ovens go out. Food gets dropped or spilled. No matter. The director just keeps on going.

"We don't stop for anything," says director Eytan Keller. "There are no retakes. They have to figure it out," referring to the featured chefs for each episode as they vie for the title of winner in an arduous, non-stop cooking contest.

Keller, in fact, embraces the mishaps. "You don't want to miss anything that doesn't go right," he says, because those moments help to underscore that the competition is a live event. They also emphasize the difficulty, unpredictability and ingenuity involved in each culinary battle. "You never know ahead of time the best moments or what's going to happen," says Keller, in the midst of directing the series' new season in New York. "Every time you do it," he says, "it's exciting and new."

Keller started working on Iron Chef America as an executive producer in 2004, when it first began airing on the Food Network as an adaptation of the eccentric, stylized Japanese culinary game show Iron Chef. By its third cycle, Keller had assumed directing responsibilities on the series. Now working on the program's ninth cycle, Keller churns out two shows a day while in production. He directs a full season (usually 20 episodes) of multi-camera line cuts in front of a live audience in the Food Network's sizable Manhattan studio. Then he returns to Los Angeles and works with the production company editing the line cuts into polished episodes.

WHAT'S COOKING: The Iron Chef and the challenger engage in

WHAT'S COOKING: The Iron Chef and the challenger engage in

culinary

combat in a kitchen

stocked to the hilt with burners,

refrigerators, ovens, sinks and every imaginable appliance.

"We've got it down to a drill after 150 shows," says executive producer Stephen Kroopnick, adding that Keller delivers more than just directing skills. "He is a guy who clearly can direct a studio-based show in a very creative manner," says Kroopnick. "But he also loves food, which is critical to the show. After all, this is a food competition show for a network that is all about food."

Similar to the format of its Japanese predecessor, every episode of Iron Chef America features an accomplished guest chef who strides into the large stage known as Kitchen Stadium through a mysterious, foggy tunnel to challenge one of the resident Iron Chefs to a cooking duel. All of the Iron Chefs are current or former Food Network personalities such as Mario Batali and Bobby Flay.

Both contenders must make five dishes based on a "secret" theme ingredient in one hour. Keller's job is to turn those 60 minutes into a thrilling, action-packed adventure, almost like a sporting event, with the outcome hanging in the balance until the very end. And because it's the Food Network, Keller has to go deeper so viewers understand the ingredients that go into the dishes, the culinary techniques applied, and even get a sense of how the recipes taste.

"You can get a director who doesn't know what a turnip is," says Kroopnick. "Eytan understands the ingredients and the nuances of what the chefs are doing. So when you have a line cut and are going into post-production, we don't miss the part where the chef fillets the fish and shows off his knife skills. Eytan looks for that and other interesting culinary moments."

For instance, in the midst of today's second battle, which features Iron Chef Cat Cora and her challenger, the inventive New York chef Julieta Ballesteros, Cora makes truffle-infused mozzarella cheese from scratch—kneading, stretching and pulling it. "Tighten on the hands," says Keller to a camera operator. "I want to see what she's picking up," he continues, as Cora wraps the mozzarella around a concoction made with the secret ingredient. [Since this episode hasn't aired yet, the secret ingredient can't be revealed.]

SHOWTIME: The action takes place in the Kitchen Stadium with hundreds of strobes flashing.

SHOWTIME: The action takes place in the Kitchen Stadium with hundreds of strobes flashing.

Before each cooking battle begins, Keller and his team shoot some introductory scenes on Kitchen Stadium. The set is divided into two parallel cooking stations. Each side is stocked to the hilt with burners, refrigerators, ovens, sinks and every imaginable appliance, including a cotton candy machine. The ceiling of the set is fashioned with hundreds of strobe lights that create fanning light beams against a black star-studded backdrop. A constant haze envelopes everything and everybody. The set has been described as resembling an orbiting space station.

But before the show takes off, the pre-battle introductory scenes are blocked and taped. This is when the show introduces the commentator and the floor reporter and judges, reveals the secret ingredient, explains the scoring, and tapes the challenger's dramatic entrance.

The challenger Ballesteros enters through a tunnel, steam rising from the floor as though she's walking over a bed of coals. She halts and assertively places her hands on her hips. The tunnel is so heavily backlit that only the outline of her body is discernible. Then front lights come up to reveal her identity.

After getting a shot of her straight on, Keller says, "Ok, we're moving on," and shifts the cameras to the opposite side of the challenger to shoot her from behind.

Keller oversees the action from his perch in the control room located above the stage. Unlike the real-time, nonstop battle that will eventually ensue, the introductory scenes are shot as many times as necessary to get a good take. Still, he tries to complete each show in about five hours.

"It's like a freight train," says stage manager Patty Riccardella. Her job is primarily overseeing the talent, making sure everyone is in the right place at the right time. "I direct the traffic on the show and keep things moving," she says.

The kooky but knowledgeable on-air commentator Alton Brown is another wild card Keller must keep in the big picture. As Brown explains to viewers throughout the battle what the chefs are cooking and how, Keller and his crew must have a camera focused on what he's talking about.

The show's dramatics are ratcheted up another notch when the host, Mark Dacascos, a martial artist in real life who is referred to on the program as the "Chairman," reveals the secret theme ingredient with a wild-eyed shout and karate-like flourish. Until then, the theme ingredient has been kept under wraps from the audience and to many others on the set. But the chefs have a clue. A day before, they receive a short list of possibilities. That way they can think about potential recipes and prepare a shopping list of ingredients.

The secret ingredient is wheeled from the prep kitchen to Kitchen Stadium in an encasement that resembles an Egyptian sarcophagus while dry ice that is being pumped into the pod keeps the ingredient fresh. For a Halloween show, cast members from the Broadway musical Young Frankenstein wheeled in offal (internal organs of a butchered animal), which was very perishable and couldn't sit for long.

As the hood is lifted, the heavy ice vapors billow and the audience tends to let out a big gasp. Over the years, the secret ingredient has been everything from garlic to beets to elk. The elk was a bit messy but fun to shoot. Its headless body had been cut straight down the middle for each chef to take half. The challenger and his chef brother easily carried their portion and started butchering it but Iron Chef Bobby Flay was a bit daunted by the size of the carcass.

SHOWTIME: Executive producer Stephen Kroopnick

SHOWTIME: Executive producer Stephen Kroopnick

says Keller (center) loves food. Stage manager Patty

Riccardella keeps everything moving.

Keller approves the secret ingredient display before it goes out. Then he strategizes with his camera operators on how to make the most of the reveal and what follows. On some episodes live fish have been wheeled out in tanks and the chefs caught them with fishing nets. "The moments that are most exciting are when we have really large ingredients or live ingredients," notes Keller, who says it's more problematic to shoot a show if the secret ingredient is a liquid. "It's harder to follow the evolution of beer," he says. "Once it's poured into a container it basically disappears."

When it's finally time for the battle to begin, the Chairman, like a boxing referee, stands between the two chefs and bellows "Allez Cuisine!" (which basically means "start cooking"), and everybody is off and running.

Two sous-chefs work alongside each chef, so there are actually six separate games continually unfolding. To keep up with the action, Keller assigns a minimum of five cameras to each side of the Kitchen Stadium. This includes at least two overhead RoboCams, two jibs, two pedestal cameras and four handhelds. And throughout the hour, as the chefs sweat it out, so do the camera operators. Keller constantly presses them to cover the competition from multiple angles and views—to "zoom in" or "open up" or "move slow and steady on that."

In fact, things happen so quickly that his camera operators have to intuit what will happen next. "It has to become second nature for the operators," says Keller, who doesn't try to sync the cameras to the running commentary provided by Brown and the floor reporter. Their play-by-play is necessary to shape the show's narrative, but the story will get refined during the edit process, where the battle is distilled to 30 minutes or less. And the occasional shaky or out-of-focus camera isn't a problem either. Those shots reinforce the live aspect.

"Tilt down to the pot," Keller tells one camera operator, as a sous-chef takes some freshly made pasta and prepares to boil it. Keller directs the cameraman to get right inside the pot. "Closer," he continues, "I want to see the pasta dripping into the water." Keller aims for the most intimate viewing experience he can pull off. "So you don't have to say, 'this is difficult.' You can see it in the chefs' faces," he explains. But just as he prepares to tell a cameraman to pan over to a chef, she unexpectedly moves out of range. "Oh, she disappeared on you," he shrugs to the operator.

"You have to be on your game or you lose it," says Keller, who, rather than sitting, always stands in the control room. Standing gives him a better view of his bank of monitors, which are stacked in two columns with one column dedicated to the cameras on one side of the kitchen and the other dedicated to the other side. The opposing cameras are aligned sideways. That way, says Keller, "I can instantly look and see what the jibs on each side are doing."

Despite the intensity of the battles, Keller finds the experience invigorating. "Seeing what unfolds and seeing the plates at the end of the hour is still magical," he says, explaining that when he gets to the judging stage, which he again shoots in a conventional, stop and start manner, he tries to tease it out as much as possible, not giving away too many clues as to who will finally win.

By then the studio is filled with great smells. "It's painful to watch the process and see these works of art come out and smell the amazing aromas and not be able to taste it," says Keller, explaining that they established a policy early on that no one can pick at the leftovers or else there might be a stampede.

Anyway, what's more important to him is that the audience watching at home doesn't ask at the end, "How did that ice cream get made? Where did that veal chop come from?" But instead, he says, "Viewers should feel they were there in the moment with the chefs."