BY ROB SEIDENBERG

TEAMMATES: 1st AD K.C. Hodenfield (right) tracks a shot.

TEAMMATES: 1st AD K.C. Hodenfield (right) tracks a shot.

(All Photo Credits: Bill Records/© NBC Universal)

On purpose or not, it looks like Friday Night Lights is about to break the Guinness World Record for "Most Bodies Crammed into a 6-by-8-Foot Bathroom." The camera A operator wedges inside a stall shower, shoulder-to-knee with his Gumby-like assistant, who trains a handheld camera on cast member Matt Lauria standing at the sink. Tumbling out into the narrow hallway two feet away, the B and C camera operators jostle for space with their assistants and a handful of PAs.

Meanwhile, in the living room of the empty tract house, director/producer Michael Waxman watches intently, one eye on the monitors and the other trying to steal a glance through the pile-up of bodies. More amused than anxious, he's devising ways to shorten the scene, if for nothing else, to provide relief to his nearly trampled crew. "We're not very precious," laughs Waxman, recalling the bathroom acrobatics. "Whatever it takes to get the scene. It's less thinking, more doing."

It's just another no-nonsense day of shooting for Friday Night Lights—although, like most setups for the critically acclaimed series, it's more like just another 30 minutes. This is a production that travels at two speeds: fast and faster. Using three handheld super 16 mm cameras, directors grab extensive coverage with just a few takes. By granting improvisatory freedom to both camera operators and actors—and eschewing rehearsals and blocking—the process stays organic and the takes maintain an immediacy. Thanks to tireless prepping from their teams, the directors get what they need quickly and speed off to the next location. And not least important, this keeps the budget of the show down. What ultimately makes the FNL process creatively effective and fiscally manageable is the combination of the directors' artistic decisions meshing seamlessly with precise logistical support from the ADs and UPMs. Each team works closely, sometimes in novel ways, to create this high-quality drama at high speed.

TEAMMATES: Director Stephen Kay goes for an organic feel.

TEAMMATES: Director Stephen Kay goes for an organic feel.

Producing director Michael Waxman (left) says it's almost like live TV.

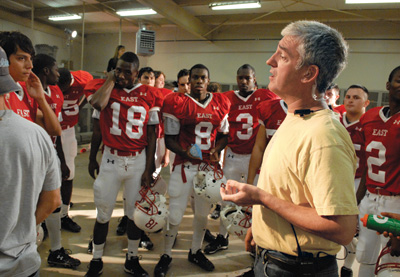

Director and co-creator Peter Berg (center) with cast members.

To thrive in such an environment, a FNL director has to be flexible, both physically and creatively. "Sure, everyone would like more takes and the time to play more with performance, but that's not what this is about," says Stephen Kay, one of the directors on the series. "This is run-and-gun, 16 mm, throw-it-on-your-shoulder-and-go. I love it, but if it wasn't your style it'd be torture. You either surrender to it or get eaten by it."

The schedule for today—one of only six days allotted for shooting each episode in and around Austin, Texas—calls for five locations, seven separate setups and eight scenes. Some of the locations will be used by Kay and his team for a separate episode in order to take advantage of the cost and time savings of setting up and transporting actors and crew. It starts at 11 a.m. and runs until 10 p.m. "It is a whirlwind," 1st AD K.C. Hodenfield understates, a moment before he takes off to scout a location for an episode to be shot next week. "To use a boxing expression, it's 'stick and move, stick and move.' We come in, take some jabs, some body blows, move on."

Back in the tiny bathroom, the scene calls for Lauria, who plays high school football player Luke Cafferty, to check out a deep purple bruise on his hip and down pills to kill the pain. 1st AD Phil Hardage announces "Rolling," but Lauria's not quite ready. "Wait a sec," Lauria says, shaking an empty pill bottle. "I need more of these." Director Waxman interrupts, "Don't worry about it. Fake it." Lauria stoops to fill his water glass from the tap. "Don't worry about it," yells Waxman. "Just start." It's not just a question of speed for speed's sake. Waxman wants to stop Lauria from overthinking.

"My mantra is: Just go. Just shoot. It'll come out right," explains Waxman, an Austin resident who also serves as the series' producing director. "I just don't want Matt to get hung up about those things. He's the kind of actor that will use those distractions to help him develop a 'performance.' But I don't want a 'performance.'"

Indeed, Friday Night Lights, which airs first on DirecTV and is then rebroadcast on NBC, strives to be as real as possible. Now in its fourth season, it's a gritty portrayal of life in the fictional town of Dillon, Texas, that focuses on the players and coaches of its high school football teams. In tone and scope, it hews closely to its source material: Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream, a nonfiction book by H.G. Bissinger, which was adapted into a feature film directed by Peter Berg. Now the series' executive producer, Berg returned to Austin to direct this season's premiere, the first episode he'd helmed since the pilot. "I'd been away for a while, and it kind of felt like a child was growing up without me, so I wanted to reconnect," he says. "It felt exactly the same—except the shooting has gotten even faster. And they really get into how fast they go. So a few times I actually had to slow them down a bit."

Many of the episodes feature football game action, for which the production flies in high-level players and NFL cameramen. ("Following that ball center frame is a lot harder than we thought," admits UPM/supervising producer Nan Bernstein.) But FNL spends much more time exploring the issues that the students and their families grapple with off the field: poverty, absentee parents, racism, alcoholism and the struggles of growing up in small-town America. "If you go back and look at the pilot now, it still tears your heart out," explains Hodenfield, who was a 1st AD on that show and returned this year to work alternating episodes. "When the star quarterback All-American-can't-go-wrong kid is paralyzed, that sends a strong message that this is going to be about a lot more than just football."

Nearly every aspect of FNL's production is unorthodox. It is, in fact, best characterized by what it lacks: no sets; no time spent blocking, lighting or rehearsing; nothing other than handheld Super 16 mm cameras. This methodology, inspired by cutting-edge documentarians like D.A. Pennebaker, was hatched during the feature and further developed during the first season by Berg; original director of photography and director David Boyd; and executive producer Jeffrey Reiner, who was a director during the first three seasons.

"The organic nature of everything is Pete's style," notes UPM Bernstein, who has been with the show since its inception. "And the whole fluid, not stuck-in-the-mud style came from Jeffrey. He freed us up, gave us the confidence to be brave and say, 'We can do that. That's no problem.' Most shows are much more staid."

GAME TIME: 1st AD Phil Hardage makes a plan with the team.

GAME TIME: 1st AD Phil Hardage makes a plan with the team."We shot the film with handheld cameras because I wanted a docu-drama feel to it," explains Berg. And although he was adamant about the unpolished look and feel of the feature and series, he was even more determined to minimize wasted time, a strong reaction to his less than fulfilling experiences as an actor. "I'd spent so much time on film sets just sitting around, waiting for crews to light and rig a scene," he recalls. "Way too much time was spent on things that didn't contribute to the end product. So I wanted to figure out a way to do it more creatively."

Using handheld Super 16 cameras not only lends FNL footage a real-life rawness, it also affords the crew great mobility. "It's not like we're carrying gigantic pieces of equipment around," says 1st AD Hardage. "The size of the cameras lets us take them anywhere and allows us to get in there and shoot three pages in an hour and a half and then go to the next spot. Our ability to be nimble is really what makes this thing hum."

As if to prove his point, 15 minutes after the bathroom acrobatics end, the house is vacant and the crew is already setting up the next location, a real estate office two miles to the east. Three hours later, they've doubled back to nearby Reagan High School, where a wall of dark clouds is gusting in from the west, obscuring the Texas sun as it drops low in the sky.

Not only is this the fifth location of the day, it's the third time today the torch has been passed between the two directorial teams, which is not uncommon for the show. "We tag-team plenty at some locations," 1st AD Hodenfield explains. "Sometimes if you have a morning scene and a night scene [in the same place], then in between someone else might come in on a different episode to get a few day scenes. At first, the bouncing back and forth was tough, but now we're all in a rhythm. Like a pinball machine, but nobody's hit tilt yet."

So as the director baton passes from Waxman to Kay, the crew at the school hustles to prep the entrance of 50 extras before the storm strikes. Inside, on the auditorium stage, tables have been arranged for tonight's "Academic Smackdown," featuring teams from four local high schools. And just as the first thunder claps, 2nd 2nd AD Tony Griffin ushers in the crowd. Extending to background actors the same courtesy the production does to its principals, there's no dawdling. And 20 minutes later, without a moment of rehearsal, they're off and rolling. "Our record is shooting a 13-page day in eight hours," laughs 2nd AD Doug Carter, who has been with FNL since the feature. "It really is like a machine."

If the shooting pace is startling, so too is the velocity with which the show jumps from location to location. While the 40-foot trucks stay put with the heavy equipment, grips, props and electrical department all have what they call "shorty-40s"—smaller trucks that zip around with mobile packages. But whenever possible, the production groups locations geographically and bundles football scenes. Locker rooms and office sets were built adjoining two frequently used football fields.

GAME TIME: Berg, Hodenfield and DP Todd McMullen size up a shot.

GAME TIME: Berg, Hodenfield and DP Todd McMullen size up a shot.

2nd AD Doug Carter works with the hair and makeup department.

UPM Nan Bernstein confers with 2nd 2nd AD Tony Griffin.

As the UPM, Bernstein is in charge of all of these logistical headaches, and, after four years on the show she doesn't miss a detail. She seems to thrive on the show's borderline chaotic nature. "When you've prepped a movie well, you feel like, 'Okay, we're under way,' and you just kind of watch things proceed," she explains. "But this is like popcorn, it never stops popping. We're always doing three shows at once: prepping, shooting, wrapping. We never have time to re-group. You need to keep your knees loose, constantly having to move to the left and right very suddenly."

With that intense speed, however, comes no sacrifice in quality, thanks in part to the triple cameras. "With three cameras you do a lot more crossfiring," explains Kay. "You can almost cover the entire scene in every setup. In a pinch you could live with just the one take. Plus you get a consistency of performance. The person talking and the other people reacting on camera are reacting exactly to what is said and how it's being said."

The way the actors are directed also contributes to the loose feel of the show. The cast has been told not to worry about being word-accurate with the script. They are encouraged to, in Berg's words, "play around with the scene as much as possible." "On a show like The Shield it's, 'Say the words. That's what they're there for,'" says Kay, who directed several episodes of the cop drama. "It's not like that here at all."

With no rehearsals or markings, the actors are given freedom of movement—which, in turn, frees up the camera operators. Since nobody knows ahead of time where the actors will go, the operators must find their own shots, "like real documentary filmmakers," says Berg. For the directors, that means setting a balance between control and chaos, making sure that the operators don't stray too far afield. Each director approaches it differently.

During a garage band rehearsal sequence earlier that day, Waxman is constantly dishing out instructions to the operators through Hardage, who passes along the commands via headset. Kay, for his part, seems more hands-off. "I like to whisper to them, 'Stay back. Don't go in yet. Make sure you get this bit,'" he explains. "But the operators all know the script, and they're storytellers, so if something is not working in the middle of a shot they're encouraged to try something else. And you have to trust that they know what they're doing."

FNL directors also must be super multitaskers and have the ability to direct a large cast and three distinct camera crews while constantly watching three monitors. "It can take a little time getting used to looking at three monitors," says Waxman. "While you're shooting, you have to think of how you're going to edit it. It's almost like live TV, except that with live TV there are so many more monitors. But it's very similar in that it's watching a performance that you'll cut."

Sometimes the ultimate challenge for FNL directors is learning how not to direct everything. For Kay, that means allowing shoots to proceed organically but being ready to capture the magical moments when they happen. "The first scene I shot when I came back this year was a scene in the locker room," he recalls. "We were all set up, ready to go, and then the entire scene took place 15 feet away from where we thought it was going to happen. We ended up shooting through stuff that we hadn't planned—through a window, through an office door. That happens a lot. You end up with divine accidents. And I think that comes across when you watch the show. It doesn't feel like everything was set up and we're performing for the audience. It feels like you're sneaking a peak at the lives of these people. Instead of seeing the wheels and strings pulling away, the best moments are the moments that are just there."