BY MARGY ROCHLIN

WONDERLAND: Favreau wanted to capture the cozy, nostalgic feel of

WONDERLAND: Favreau wanted to capture the cozy, nostalgic feel of

Christmas classics for Elf, with Will Ferrell. So he tended to avoid

CGI in favor of traditional techniques.Jon Favreau's first experience on a working film set can be traced back to Turk 182! What part did he play in the creation of the 1985 fighting-city-hall comedy? Faux crew member. "It was a closed set, so my friend and I both brought rolls of duct tape so we looked like a PA or a grip, and then we just tried to blend in," says Favreau, who can still remember the feeling of being an 18 year old standing on Manhattan's 59th Street Bridge at night watching a movie being made. "All the lights were shining and it felt like Oz and we just wanted to be there. It was so magical."

How much Favreau has managed to hold on to that awestruck teenager is evident by the series of wonder-filled movies he's directed—Elf, Zathura and Iron Man—which manage to strike a balance between special effects wizardry, laugh-out-loud comedy and emotion-stirring story. Viewed chronologically, his successive projects have expanded measurably when it comes to budget, moving parts and the degree of skill required. Yet Favreau is entirely self-taught, learning the nuts and bolts of directing while acting in films, starting in 1993 in the feel-good sports movie Rudy. Whether or not his name was on the call sheet, he showed up on the set every single day. "I got to talk to everybody," says Favreau, who picked director David Anspaugh's brain, quizzed cinematographer Oliver Wood and hung out in the cutting room as Oscar-nominated editor David Rosenbloom worked on the rough assembly. "I would just watch what they did and as long as I didn't get in the way and asked questions in a respectful way, I found that people had tremendous patience with me."

MOVIE MAGIC: Favreau directing the intergalactic adventure Zathura.

MOVIE MAGIC: Favreau directing the intergalactic adventure Zathura. The director positions cast on Elf.

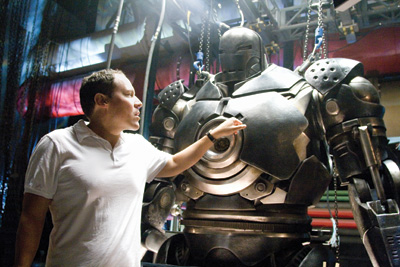

The director positions cast on Elf. Favreau explains a scene to Robert Downey Jr. on Iron Man.

Favreau explains a scene to Robert Downey Jr. on Iron Man.Eventually, after the success of the 1996 hipsters-in-Hollywood indie film Swingers, which Favreau wrote and starred in as the hangdog Mike obsessed with his ex-girlfriend, he got the opportunity to make his behind-the-camera debut with Made. A dark comedy, it told the story of two hapless working-class pals—Favreau and Swingers co-star Vince Vaughn—who get entangled in a money-laundering gambit. Forgoing the traditional film class route, Favreau directed Made by relying instead on the reams of mental notes he'd stored in his head about what filmmakers did to make a production sparkle and what kinds of behavior ensured disaster.

"I suppose you can go to school, learn theory and then make your own movies with a bunch of other inexperienced people," says Favreau. "But the path I took was to be around very experienced filmmakers and crew members. I watched the way directors carried themselves, the ones that lost their shit on the set and what that resulted in. I paid attention to the ones who were calm, the ones who were funny, the ones who seemed confident and the ones who seemed insecure."

As for how to get the most out of his cast, Favreau settled on a hands-off approach knowing from his own acting experience just how much mileage one can get out of simply providing space to create. "I get people whose instincts are going to be right, whose sensibilities are good, and I let them go," he explains.

For Iron Man this meant listening while his star, Robert Downey Jr., presented an idea for how that day's scene might be reworked so that a conventional press conference could be upended by having his character ask the assembly of journalists to sit on the floor. Favreau wasn't sure it was worth the time and trouble, but he gave the go-ahead.

"It didn't totally make sense to me, and we had to change the lighting and the camera positions," says Favreau. "But [Robert] did it and it worked. Sometimes it doesn't. But this time it did—and it really helped the scene." He also recalls that once he sensed the snappy chemistry between Downey Jr. and Gwyneth Paltrow, who plays his willowy secretary Pepper Potts, Favreau made sure to reserve room in the shooting schedule for the pair to improvise their dialogue while two cameras rolled.

"I always want to get that real moment, that spontaneous, unexpected thing to happen in scenes," says Favreau, who feels that in this way Iron Man became a much richer film-going experience. "Whatever it is, Iron Man did not feel expected and predictable at every turn," says Favreau. "I don't like that kind of movie where it's just about eye candy." Often in tech-laden superhero films, Favreau explains, giant asteroids can explode and growling space creatures can menace, but the audience leaves the theater feeling cold. "That's because the action pieces just feel like an arbitrary series of events. People think that tech is what gets you but really it's the story."

A story-driven approach might sound surprising coming from a director currently up to his ears in top secret, cutting-edge special effects on Iron Man 2. Yet even on Elf, the first feature film he did that required visual effects, he stayed low tech, trying his best to steer clear of CGI in favor of old-fashioned techniques like forced perspective, stop-motion and choppy two-frame animation. One reason he felt like staying basic was that he knew it would help suggest the cozy, nostalgic feel of Christmas classics like the Rankin/Bass television special Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. Aside from that, he was thrilled at the idea of having things like an animated snowman in sunglasses dole out comforting advice to a live-action Buddy the Elf (played by Will Ferrell in yellow tights and a belted, green-embroidered cutaway jacket) before he leaves the North Pole for the glittering lights of New York City.

"I love the craftsmanship of it. I love the models. I love miniatures," says Favreau, who decided he'd save the computer graphics for the moment in the movie when Ed Asner's sweetly gruff Santa Claus must zoom over Central Park in his carved wooden sleigh and eight reindeer. "I was very much not a fan of CGI. I felt it went wrong as often as it went right."

Lately, though, Favreau has begun to warm up to using digital visual effects in his films. He credits this shift with improvements in the technology as well as the fact that he's become more proficient at communicating with his effects team. "Tech-wise, if you have a good supervisor and a good house, hard surfaces like a car or a robot can be [rendered] to the point that you cannot tell them apart, side by side, from the real thing." Because of this he realized how fortunate he was to choose Marvel's man-in-a-metal-suit franchise as opposed to the one involving a meek doctor who is exposed to gamma rays and morphs into an enormous green monster. "Biological creatures are doable," says Favreau. "But it's a lot harder to make the Hulk look real than Iron Man. I don't ever want to go past the point where it doesn't look real. When you lose the reality of it, you lose the emotional connection and that's when you end up feeling like you're watching a video game."

It's not surprising that Favreau is so concerned with never letting anything overpower the prevailing mood of his movies. In all of his films, the protagonist at the center of the story is reminded every single day of how isolated he is from the rest of the world. "I do see loneliness as a repeating theme in my movies," says Favreau, "but loneliness isn't the fun part of a movie for me. The fun part is banishing the loneliness, and offering the promise of love and communion at the end."

While he'll use everything in his arsenal from lighting to set design to camera angles to help communicate his characters' feelings, Favreau still says, "I don't come from the visual filmmaking side of movies. I come from the writing-acting-storytelling side. Rarely do I have—maybe two or three in a whole movie—a visual image that I want to chase. It usually is an emotion I want to chase, or a feeling or a character progression that I understand. That's what leads the way for me."

MOVIE MAGIC: Despite his tech-laden superhero, Favreau didn't want to just create

MOVIE MAGIC: Despite his tech-laden superhero, Favreau didn't want to just create

eye candy for Iron Man.By way of explanation, Favreau offers the example of the request he received from New Line when he was in pre-production on Elf. "The executive said, 'We need a set piece like the one in Big where Robert Loggia and Tom Hanks play Chopsticks on the big piano at FAO Schwarz with their feet.' So I had to sit down and figure out what was it about that set piece that these people wanted. It wasn't a piano. It wasn't necessarily the toy store. But it was very memorable," says Favreau, who concluded that what the powers-that-be felt was missing was a bonding moment. "It's the thing that makes you feel something and tingle when you see it." His solution was to have Buddy the Elf win over his younger half-brother—who is embarrassed by his gushing, cartoonishly dressed older sibling—by making and hurling a million snowballs when they're ambushed by a group of older boys in Central Park. "It's a great set piece, but not because it was so well-conceived visually. It just served the story function. People will remember things as funnier, scarier, more satisfying if you tie it to story. If you don't, you're making parallel movies that don't meet."

One other crucial lesson Favreau learned from Elf, which was shot almost entirely on location in Manhattan, was what it felt like to spend six months away from his family in Los Angeles. "Part of what makes my movies work is who I am and [being home] is part of that," says Favreau, 43, who has three children under the age of 8 and now includes a special "let's-keep-it-local" rider in all of his contracts. "My way is if I can shoot it here, I want to because it's better for the movie. The crews are great and everyone is sleeping in their own beds. You've got the whole film industry here."

Having seen how rebates and tax credits offered by other states have hurt production in Los Angeles, Favreau also convinced Marvel Studios to let him make Iron Man 2, which is budgeted at a reported $140 million, on his home turf. While he makes sure to acknowledge the effort California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger recently put into establishing the state's first-ever 20 percent-25 percent tax credit, he adds, "It's very small compared to other states."

Because he's concerned about Los Angeles losing its luster as a filmmaking mecca, Favreau has also turned into a runaway production activist. "I loved coming here 15 years ago, and walking on the backlots and watching people make movies and the development and the talent that's here," says Favreau, sounding once again like that awestruck teenager on the bridge. "It was mind-blowing to me. So I want to try to preserve that in whatever way I can in California."