BY GARY GIDDINS

John Frankenheimer (Credit: DGA Archives)

John Frankenheimer (Credit: DGA Archives)

Criterion's absorbing three-disc DVD set, The Golden Age of Television, reminds us that the art of live theatrical broadcasting presented a unique challenge—particularly to directors—born of a new and fleeting technology. Like silent movies, the field was doomed to obsolescence by the technology's inevitable development. What synchronized dialogue did to cinematic pantomime, tape did to real-time television. But in its brief, shining moment, barely a decade from the late 1940s to the late 1950s, live TV created a hybrid medium unlike anything before or since. Not surprisingly, it created its own generation of directors, writers, cameramen, and actors. Some of them expanded into film and theater; others remained with television; and many went on to become Guild leaders.

The "golden age" of the title is not meant to suggest that television was better in the 1950s, but to denote the era when its innovators were first learning the medium, discovering its potential, and finding fixes for exceptional problems. The directors were confronted with a form that was neither theater nor cinema, but had aspects in common with both. The theatrical parallel of a real-time presentation, interrupted by four or six commercial breaks (as opposed to one or two intermissions), was undermined by the fact that television democratized its plays: No matter how good or bad a show, the opening night was also the closing night. More significantly, every moment was framed, shaped, and choreographed by the director and his cameramen. Rehearsals were not only about blocking actors, but figuring our camera moves. Live TV had close-ups, fadeouts, crane shots, two-shots, over-the-shoulder dialogues—all familiar movie techniques, except that the cameras were attached to small tractors and lacked zoom lenses. Edits and second takes were not an option. If a cameraman missed his mark or an actor went up on his lines, the director's only fix was Pepto-Bismol.

An important distinction between live TV and other dramatic mediums was its balance of power between directors and writers. By 1950, the writer ruled Broadway—not even a name as famous as Elia Kazan sold as many tickets as Tennessee Williams or Arthur Miller. In movies, the opposite was true: few people knew or cared who wrote the latest feature by John Huston or Alfred Hitchcock or, for that matter, Kazan. Television maneuvered between those two poles.

As far as the public and critics were concerned, most of the attention on these live dramatic presentations was lavished on a bastion of young writers who had enjoyed, up to that point, little if any success in film or theater: Rod Serling, Paddy Chayefsky, Reginald Rose, J.P. Miller, Gore Vidal, Horton Foote, and others. In TV, they were treated like playwrights.

Delbert Mann (Credit: DGA Archives)

Delbert Mann (Credit: DGA Archives)

Yet watching the eight programs collected in The Golden Age of Television, and similar anthologies, including Koch Vision's 17-show set, Studio One Anthology, it is impossible not to appreciate the degree to which live television was ultimately a director's medium. The audience that tuned in to CBS' Playhouse 90 on February 14, 1957, to see Serling's adaptation of Ernest Lehman's short story, The Comedian, about a TV star's relentless, ruinous egotism, may have been, as intended, mesmerized by Mickey Rooney's bravura performance. But today's audience will marvel at (and very likely replay) the opening scene in which the action behind and before the camera is turned into a seamless, swirling labyrinth of activity. It will admire the way a tracking shot of the character played by Kim Hunter takes her past the malicious columnist played by Whit Bissell, while Edmond O'Brien makes his dramatic entrance from the other side of the screen, hurrying into the control room to confer with the show's director. All this is accomplished in one precise camera move before the scene abruptly switches to a close-up photograph of Rooney and a slow pan to allow O'Brien time to dash onto the set for a completely different scene.

The Comedian was the work of the era's most prodigious and energetic director, John Frankenheimer, who made an astonishing 152 programs in seven years, including adaptations of Faulkner, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Cornell Woolrich. You don't have to be a cineaste to render unto the director his due. The fact is that The Comedian is an entertaining show, but by no means a profound play. Its primary failing is that the protagonist is supposed to be a comedic genius whose brilliance mitigates his foul behavior, but we are never allowed to see or hear an inkling of that brilliance. Rooney's scenery-chewing is impressive, but his entire performance is set at max. He shouts even when dining in a public restaurant.

Yet this and several other programs in the Criterion set remain compelling stuff. Despite the dim 16 mm kinescope picture and shallow sound, our interest is sustained by the palpable backstage tension (though only The Comedian puts it front and center as its subject), which is almost always apparent as part of the medium's gestalt in all the shows. Consider, for example, J.P. Miller's Days of Wine and Roses (1958), which Frankenheimer directed in a near-documentary mode, allowing actors Cliff Robertson and Piper Laurie to take their time, building scenes to a climactic pitch. Oddly, Blake Edwards' hugely successful film version (1962) now feels stilted, even sentimental, while the television original retains a slice-of-life immediacy.

Frankenheimer says, in one of several DVD director commentaries, that he never left television; television left him. After the introduction of tape, a live drama could only be made as a stunt, a pointless exercise. The made for TV movies that became broadcasting staples from the 1960s on inevitably made use of all the edits, retakes, and filming (or taping) schedules that brought television closer to the filmmaking process. Inevitably, many television directors made the transition to movies, including Franklin J. Schaffner, whose take on Rose's Twelve Angry Men (1954), is a highlight of the Studio One Anthology. It isn't as richly fleshed-out as Sidney Lumet's 1957 film, but it has a rhythm and method of its own. Robert Cummings' everyman juror sets the ball in motion with an inquisitive and vulnerable cluelessness, as opposed to the film's Henry Fonda, who is obviously the smartest man in the room. Similarly, we expect boorishness from the film's veteran villain Lee J. Cobb, while the evil of his TV counterpart, Franchot Tone, emerges gradually. And if Lumet makes us forget we have spent 90 minutes in a room, Schaffner and his company really do spend nearly an hour in a room, and make the confinement work for them.

A director whose reputation is likely to get a charge from the recirculation of his television work is Delbert Mann, whose film career defines the idea of making a finished, even established script come alive on screen. His films of successful plays improved on Terence Rattigan's Separate Tables (1958) and achieved a nearly perfect transformation of William Inge's underrated The Dark at the Top of the Stairs (1960). After a decade of hits and misses, he returned to television in the early 1970s, as made for TV movies became increasingly ambitious, picking up where the live anthology dramas left off. Mann filmed adaptations of David Copperfield and Jane Eyre, as well as original teleplays. His film career began with an adaptation of his television benchmark, Chayefsky's Marty. But you have to see the original 1953 broadcast to realize how good Mann could be. Despite sadly ludicrous dialogue in which purportedly ugly people refer to themselves as dogs, he exacted a performance of power and uncharacteristic understatement from Rod Steiger, and created a kind of relaxed tension by setting up long two-shots in which the actors have to ignite the sparks. Steiger's "wadda ya wanna do" chats with Joe Mantell, the heartless drabness of the dance hall, and the hilarious literary discourse ("dat Mickey Spillane sure can write") make for great television. These same scenes became strangely polished and sanitized on film.

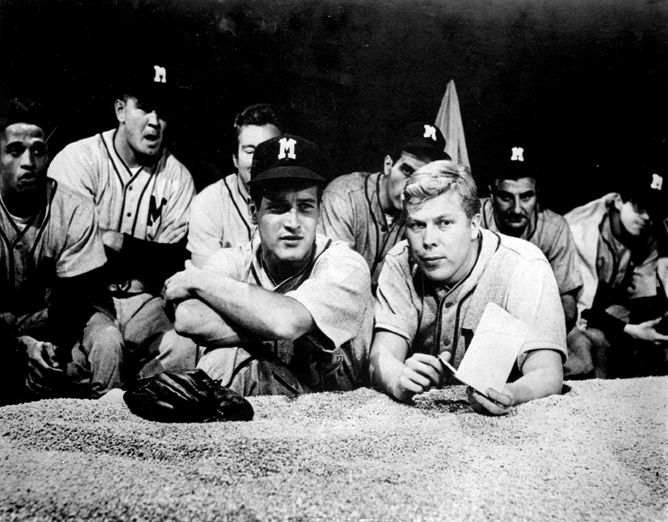

Bang the Drum Slowly (Credit: Criterion)

Bang the Drum Slowly (Credit: Criterion)

Some talented and prolific innovators of live television stayed with the medium, confronting the more conventional challenges presented by tape. Fielder Cook directed more than 60 episodes of Lux Video Theater (including the fabled and unavailable The Betrayer, with Grace Kelly and Robert Preston), before making Serling's Patterns (1955) for Kraft Television Theatre. Serling may have been bedeviled by censors and craven producers, but he got more mileage out of unhappy or static endings than almost anyone working in Hollywood in the mid-1950s. Crude manipulation triumphs in The Comedian; compromised dignity closes Requiem for a Heavyweight (part of the Criterion set, directed by Ralph Nelson, who also directed the tamer film version); and Patterns ultimately knuckles to the glory of big business.

Cook got to make the 1956 film version of Patterns, but the challenges of live television suited him better. With scenes cut against a motif of clocks, the broadcast version of Patterns moves like wildfire, the actors constantly walking into or away from the camera. Cook used harsh lighting and layered soundtrack effects: trains, mimeographs, the faint echo of a conversation heard off-screen. Richard Kiley, Everett Sloane, and Ed Begley are superb, with Begley leaning into a close-up in which his usually malevolent homeliness is transformed into an unexpectedly appealing candor. Cook later directed dozens of television series, and several made for TV benchmarks, including Judge Horton and the Scottsboro Boys (1976) and his last film, a version of The Member of the Wedding, with Alfre Woodard and Anna Paquin (1997).

Another director whose light shone best on television is Daniel Petrie. Working with a canny Leo Penn adaptation, he managed to stage a respectable Julius Caesar (included in the Studio One set), more kinetic than the Joe Mankiewicz film, with an especially lean and hungry Shepperd Strudwick as Cassius. Petrie is represented in the Criterion set by a lyrical but lackluster vehicle for Julie Harris, James Costigan's A Wind from the South (1955), and the lively if intransigent Bang the Drum Slowly (1956), which partakes of the 1950s notion (cf. Damn Yankees) that professional baseball was dominated by semi-literate Damon Runyon types. In the latter, Petrie nurses a slightly frazzled Paul Newman (he flubs a line in his big closing speech) and Albert Salmi through a complicated production in which the Newman character has to pop in and out of scenes, playing his part and narrating the story. Arnold Schulman's play isn't much and the star is on a learning curve, but the director has it all mapped out and timed to a millisecond. As with many of these broadcasts, the tremulous uncertainty of the medium is more captivating than the material. Live television was an art unto itself—no longer possible to produce, but well worth revisiting.