BY DAVID MERMELSTEIN

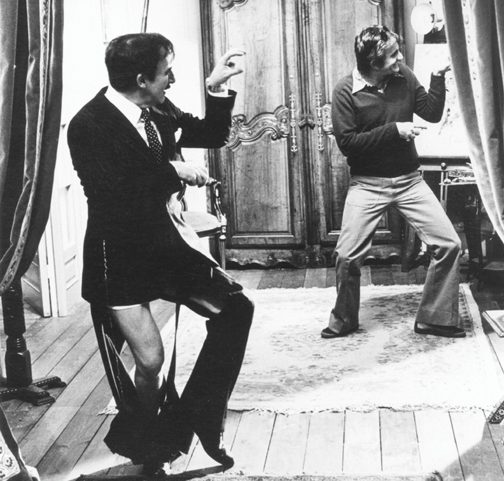

PARTNERS IN CRIME: Although they had a highly contentious

PARTNERS IN CRIME: Although they had a highly contentious

relationship, Blake Edwards and Peter Sellers had great comic

chemistry on the set. (Photo Credits: BFI/Photofest)Blake Edwards' classic comedies have always had a dark side, so it's not surprising the director best known for his series of Pink Panther films has mixed feelings about being celebrated solely as a master of the pratfall.

"It gets a little tiresome," he admitted recently, sitting in the light-filled living room of his Brentwood home. "I have made other things. I don't mind being the comedy maven." He pauses. "But I do, I guess." And yet here he was—closing in on 87, his memory razor-sharp—expounding on the art of comedy by recalling not just some of the more celebrated scenes in his oeuvre, but also how it was that he, um, stumbled into such fare to begin with.

Edwards insists he never embarked on a career as a comedy director. It just sort of happened. "I learned a long time ago," he says, "that if I have a talent for directing comedy, it's best not to question it. Do it." He will forever be associated with the eight Pink Panther movies he made between 1963 and 1993, especially the five starring Peter Sellers as the bumbling Inspector Clouseau. It was a fruitful if complicated relationship.

"We clicked on comedy," Edwards says, "and we were lucky we found each other, because we both had so much respect for it. We also had an ability to come up with funny things and great situations that had to be explored. But in that exploration there would oftentimes be disagreement... But I couldn't resist those moments when we jelled. And if you ask me who contributed most to those things, it couldn't have happened unless both of us were involved, even though it wasn't always happy."

The director maintains that Clouseau's appeal, then and now, lies in his perseverance. "Thou shalt not give up," says Edwards, who co-created the character. "That is the essence of Clouseau. If you don't have that, it's hard to find a reason for him. He never thinks he's going to fail. I really feel that's my secret."

More than once, Edwards says, he swore off Sellers. But until the actor's death in 1980, they reunited for six films, including The Party (1968), a '60s bash utilizing classic conventions of comedy such as sight gags and mistaken identity. In fact, it was originally intended as a silent film, "but the minute we got on the set and Peter tried to do what he did," Edwards says, "it was perfectly obvious he could not be a silent character. And I said, 'Oh, let's just do it with a script,' so we made it up as we went along, from beginning to end. I never thought about making a silent movie again. It was only with Peter that I considered it, because we were both so invested in silent films."

Growing up in Hollywood, the son of a studio production manager and grandson of a silent film director, Edwards says his unhappy childhood was ameliorated by movies, particularly the work of the great silent clowns—Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, and Laurel and Hardy.

In later years, he missed a chance to meet Laurel, and though he did come to know Lloyd, it was not as a protégé. "We had a lot of talks but I didn't think of him as some steppingstone to a career," the director reflects. "I wasn't at that stage. He once told me about how they shot the famous clock scene in Safety Last! But I wasn't trying to find out something that was going to benefit me, although I guess eventually it did."

He did better when it came to Leo McCarey, who, as the director of Duck Soup, Ruggles of Red Gap and The Awful Truth, knew more than a little about comedy. In fact, McCarey became something of an unofficial mentor to Edwards. He learned from him the importance of timing, later one of the hallmarks of Edwards' comedy.

"One day in the late 1940s or early '50s, McCarey started talking about staging a gag," recalls Edwards. "I'd never heard anything like it. His example was a young man and his sweetheart who had just spent a day in the park. They go to a streetcar, and he bids her off. In those days, streetcars had fixed steps, and as she stood on the step and said goodbye, the streetcar began moving. And he walks along with it, all the while extolling his passion for her. But pretty soon, the streetcar picks up too much speed, and he gets clipped from behind and lands in the middle of the road. She keeps waving goodbye, and he's sitting disheveled in a puddle waving back. End of joke? No. He now realizes he's in danger of getting run over, and he does a routine of picking up the stuff that's fallen out of his pockets and putting it into a hat. Finally, he makes it to the curb. End of joke? Not at all. Now an old lady passing by goes through the hat, takes a pen from it and puts a nickel in the hat. That was the end. I can't tell you how many times I've thought about that and wondered if I could top it. And if so, how?"

Edwards certainly tried in The Great Race (1965), his most obvious homage to the silent clowns and their antics. It's not for nothing that the dedication "For Mr. Laurel and Mr. Hardy" appears on screen even before the Warner Bros. logo. The film is replete with physical gags, but probably none more famous than the orgiastic pie fight that marks the climax of the film's Prisoner of Zenda subplot.

Edwards demonstrates the proper technique for hurling a pie at Natalie

Edwards demonstrates the proper technique for hurling a pie at Natalie

Wood in The Great Race. (Credit: AMPAS) Directing wife Julie Andrews in Victor/Victoria. (Credit: Warner Bros.)

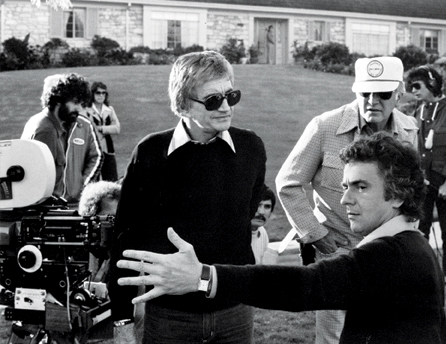

Directing wife Julie Andrews in Victor/Victoria. (Credit: Warner Bros.) Edwards and Dudley Moore work on a scene from 10. (Credit: Warner Bros.)

Edwards and Dudley Moore work on a scene from 10. (Credit: Warner Bros.)Edwards happily acknowledges his indebtedness to the silent clowns. "Absolutely," he says, "that's why it's in there—not necessarily that I was going to do it better, but that I would be original enough to do it bigger." The way Edwards planned it, everyone from Natalie Wood to Jack Lemmon to Peter Falk would quickly be covered in multicolored cream, but Tony Curtis, dressed completely in white, would remain spotless as he walked through a gauntlet of airborne desserts—until, that is, Wood lands him one square on the puss.

As it turned out, the scene worked better than Edwards had dared hoped. "It was almost magical in a way," he marvels, "because I expected to have to shoot in cuts to get Curtis to walk through this carnage and be untouched. So I did a big master shot with three cameras, and the actors threw things at him and around him, but somehow nothing ever landed on him. We got it all in one take. I think one camera was in close, one medium and one full-shot."

Another important lesson from his silent heroes, echoed by McCarey, was the connection between pain and comedy. "When you start analyzing the great film comics," Edwards explains, "they were constantly beating each other up and falling down stairs and tripping over pants. They got their laughs through a sort of carnage, and I think I started doing that, too."

In this vein, he remembers another McCarey tale, this one a true story in which a woman with a husband in the hospital goes seeking financial assistance from a charity board on which McCarey sits. She explains how her husband's heart attack and her own arthritis have left them destitute, and how her husband had become so anxious about their future that he'd asked for a cigarette, which she couldn't light for him. So he had to do it himself, right there in his oxygen tent.

"When he lit it," Edwards relates, "there was an enormous explosion that blew him right into the maternity ward. And everybody on this charity board—these dozen stern-faced people—they just broke up. McCarey said that it couldn't have been funnier. But it wasn't funny at all, of course. A man had been blown-up. And from this story, I learned about pain and eliciting laughter. I paid attention and it served me well."

Examples abound of the director incorporating these lessons in his work, with Clouseau's violent mishaps topping the list, not to mention Jack Lemmon's Prof. Fate in The Great Race or Dudley Moore's George Webber in 10 (1979). But with Edwards' collaboration with Moore in 10, the story of a middle-aged man set loose in the sexual revolution, the director took the physical comedy of his earlier work and added a new level of social commentary. Still, there were plenty of pratfalls. Separating who is responsible for the laughs in a comedy is no easy task. "It's a little hard to answer who does what," says Edwards, when asked who is responsible for the laughs in a particular scene in 10 where a voyeuristic Moore gets beaned by his outdoor telescope and tumbles down a hillside, only to end up in his swimming pool once he makes it back up.

"Rolling down the hill was mine," says Edwards. "Sure, Dudley added to it, because he's Dudley. He was enormously talented. I may have written in the script something less than, or beyond, what we got to when we were shooting, but near as I can remember, that was all my stuff. But when you give a genius direction, then he brings his genius to it." By way of example, Edwards mentions the beach scene in which Moore first sees Bo Derek in a swimsuit. "When he went hopping across the hot sand, his physical reaction to a scripted moment made it that much better," the director says. "You could say Dudley elaborated on the gags. Like when he's trying to drink coffee after seeing the dentist but his mouth is frozen from the anesthetic. Though the shot was scripted, it's how he did it that made it great. I was lucky to have someone that talented to give my character life, but those moments that accentuated the life and the humor were essentially mine."

10 marked something of a turning point for Edwards as a comedy director, signaling a shift toward material that would increasingly involve male protagonists in the throes of midlife crises in films like The Man Who Loved Women (1983), That's Life! (1986) and Skin Deep (1989), which, despite his decision to include glow-in-the-dark condoms, he considers one of his funniest films. He gives much of the credit to the performance of John Ritter, who in one scene is nearly electrocuted by an ex-girlfriend. "You can't make anybody funny," Edwards says. "You can give them funny things to do. But they have to have the instinct to embellish and make it rich. I gave him the idea and... he had us all falling down laughing. It was a first take."

One film that didn't have a male hero–well not exactly-was Victoria/Victoria (1982), which starred Julie Andrews, Edwards' wife of almost 40 years, as a down on her luck cabaret singer in 1930s Paris who becomes a sensation when she starts performing as a man.

Edwards directed his wife in six films, but insists it was no big deal. "I wish I could say that it was that different, but it wasn't," he maintains. "When we were working, she was a leading lady that I would go home and sleep with. We didn't have any arguments professionally that I can recall. It was always very pleasant."

Victor/Victoria was a frothy tip-of-the-hat to another of the director's idols: the incomparable Ernst Lubitsch. "Sure it was an homage to Lubitsch," Edwards says. "You would be a fool not to acknowledge—if only to yourself—your betters. But I didn't go in saying I was going to mimic Lubitsch or be so blatant as to copy him. The film was a kind of silent acknowledgement to the genius of Lubitsch, the style and sophisticated humor and sexuality. I loved Lubitsch from the first frame I ever saw. I loved the characters. They made me feel at home."

It's a long way from the sophisticated, slightly risqué comedy of Victor/Victoria to today's more explicit, no-holds-barred films, but Edwards still tries to keep up at home. However, not very much of the new stuff is to his liking. "I don't feel laughter like I used to," he says. "I don't know whether it's the material or me becoming older and more grouchy. But for me, it just isn't that funny most of the time. I find it extra cruel, even beyond the man and the streetcar I described. I think we've lost sight of some of the subtle humor. Doctors acknowledge that laughter is great medicine, and for me lately there's too little of that [in movies]. But," he says, returning to where he started, "there's always Stan and Ollie."