BY JEFFREY RESSNER

Photographed by David Strick

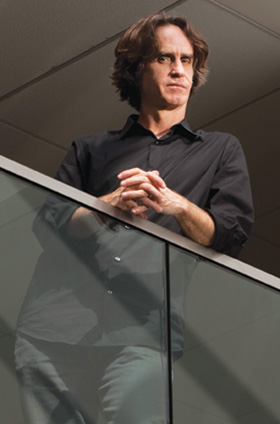

Jay Roach charges into the meeting room of his Santa Monica office exuding boundless energy. He is so unassuming and self-deprecating, you might not peg him as the director of some of the most successful comedies in film history. Typically, he joked in a piece he wrote for the DGA Quarterly a few years ago that he didn’t always feel “directorial” on the set, and that he was working on channeling his “inner Eastwood.”

Jay Roach charges into the meeting room of his Santa Monica office exuding boundless energy. He is so unassuming and self-deprecating, you might not peg him as the director of some of the most successful comedies in film history. Typically, he joked in a piece he wrote for the DGA Quarterly a few years ago that he didn’t always feel “directorial” on the set, and that he was working on channeling his “inner Eastwood.”

Nonetheless, he has demonstrated a keen eye and impeccable comic timing directing the inspired camp of the Austin Powers trilogy and scored back-to-back blockbusters with the screwball charm of Meet the Parents and Meet the Fockers. And then, as if to confound expectations, he took a left turn with Recount, HBO’s engrossing portrait of the 2000 presidential election, for which he won the DGA Award for Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Movies for Television, as well as an Emmy.

Visitors wondering about Roach’s comedic influences need look no further than the walls of his production office, the aptly named Everyman Pictures. Framed one-sheets tout some of his favorite funny movies—Hal Ashby’s cult classic Harold and Maude, Blake Edwards’ 1960s rave-up The Party, and Woody Allen’s soulful Annie Hall. And as a wild card, suggesting perhaps a darker or quirkier side, is a poster from David Lynch’s first feature, Eraserhead.

Catching up with Roach in between preproduction chores on his next directing project, Dinner for Schmucks (a remake of the French drawing-room farce Le Dîner de Cons), and locking down the final edit for Brüno, a film he produced in his ongoing relationship with Sacha Baron Cohen, he proved to be an articulate and thoughtful student of the genre. Rather than begin with small talk about his background (he studied economics at Stanford and cinematography at USC), Roach jumped immediately into the subject at hand: comedy.

Jeffrey Ressner: Do comedy directors have to be funny?

Jay Roach: It’s my job to know what’s funny. No one ever really knows, but my job is to be a good guesser at what’s funny, to sit in the chair as an audience member and say, ‘Make me laugh.’ And, so, on many of our dailies, you can hear me laughing.

Q: What about your own sense of humor? Are you a funny guy?

A: Definitely not. I can hold a conversation and find irony. But when it comes to getting people to laugh, I’m too anxious to be funny. My mind is always busy enacting worst-case scenarios to focus on how to amuse others or myself in the room. I’d love to laugh more in real life, and I think that’s why I love comedy so much. When I saw Annie Hall, for instance, I’d been through this painful, horrible relationship and I just didn’t see anything funny about anything. But I remember that film made me laugh so hard. It was inspirational to think you could tell a story and make people feel a little better about their own lives.

LOOKING GOOD: Roach was always ready for surprises from Mike Myers on

LOOKING GOOD: Roach was always ready for surprises from Mike Myers on

Austin Powers in Goldmember. (Photo Credit: New Line/Everett Collection)

Q: Sometimes in the Austin Powers and Meet the Parents movies, the action seems so spontaneous, like it’s happening for the first time. Do you encourage improvisation?

A: Obviously there’s a big difference between the way an Austin Powers movie looks and feels as compared to Meet the Parents, and certainly, a drama like Recount. But there’s an approach in common across those multiple projects. And it’s mostly just [focusing on] script and cast. I literally just say that to myself over and over: script and cast, script and cast, script and cast. Because you’re pressured to make decisions about so many other things and it’s associated with decisions about the script and who’s playing the characters. Perhaps it’s a cliché, but the more specific and well thought out that script is, the more license you have to improvise off of it because you know the scene. Particularly in comedy, I prefer to work with actors who can go off the script and try things that would surprise you. Often what’s scripted is very good dialogue. But once the actors have prepared and rehearsed and worked it through, it can only feel so spontaneous. To get real spontaneity sometimes, something new has to happen.

Q: How do you allow for improvisation in your shooting schedule?

A: Well, improvisation loves chaos, it loves the freedom to try something and then to keep shooting at it. I remember on the first Austin, we were shooting in a direction toward Seth Green, playing Scott Evil, and off-camera Mike started telling him to shush: ‘Shhh! Shhh!’ He was just doing it to mess with him from off-camera, to try to provoke a reaction, and it was so good that I shot it and said, ‘Okay, now you got to keep doing that.’ We had to turn all the way around and it cost us probably a third of a day. But if you’re keeping everything else moving, and you’re keeping an eye on the priorities of what you hope the audience is going to enjoy, if it’s really good, you’ll blow off something else to buy yourself that flexibility.

Q: Your crew must love it when you pull stuff like that.

A: It’s actually so important for me that I’ve cast the crew, if you will, and chosen crew members—particularly the 1st AD and cameraman—to expect their day to be a little bit in flux, to be very nimble with their crews, to bring people on their team that like comedy enough that they won’t roll their eyes when I say, ‘Okay, we’re turning around and doing that whole thing again ’cause it’s just way funnier.’ I’ve been on crews before where there’s a sense that these are the shots and once we get them done, we’re done. But it doesn’t work that way in comedy. I’ll definitely float the message: ‘Look, everybody get ready for a long night, we don’t have it yet. I don’t know what it’s even going to be, but I bet it’s going to take a while to shoot enough takes to find it.’

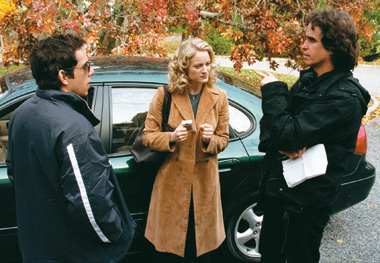

HOME ALONE: Ben Stiller (left), Teri Polo and Roach rehearse a scene

HOME ALONE: Ben Stiller (left), Teri Polo and Roach rehearse a scene

on

Meet the Parents. (Photo Credit: Universal Pictures)

Q: How does that affect your budget?

A: You have to stick to a budget and a schedule. Certainly Meet the Parents and Meet the Fockers were a little different than the Austin films, but we always come in on time with the pictures where I’m anywhere in charge of the schedule, because I like the shape of the box. I like having limits and deadlines. It puts pressure on all of us. As soon as you let it slide and say, ‘Oh, we’ll just come back tomorrow and redo the whole thing,’ a kind of sloppiness kicks in where people stop tensing up to get the best possible stuff. So I prefer to keep the pressure on everybody and say, ‘We’re gonna have chaos—and we’re going to hit the budget and the schedule.’

Q: Speaking of crews, do you find it helpful to work with the same directing team?

A: Yeah, I love to work with people that I’ve counted on to deliver before. I’ve had such great collaborators that it’s so unfair for me to get all the credit for my films. I’ve just had tremendous 1st ADs, cinematographers, editors, performers. I could go down a long list. Josh King was my 1st AD on Austin 3 and on Meet the Fockers, while the fantastic Richie Cowan was 1st AD on both Mystery, Alaska and Meet the Parents. I’ve worked with the same editor for years, Jon Poll, and produced the first feature he directed, Charlie Bartlett, because I always thought he should be a director. He thinks like a director.

Q: Mike Myers once complained about how hard it is to be funny at 6:30 in the morning. How do you arrange your shooting day?

A: It’s not just Mike. I’ve encountered other performers who’d get there right at 7:00 and you could shoot like crazy, but it wouldn’t be as good as what they gave later in the day. I’ll often ask the AD if there’s something that can be covered or establishing shots, whatever, particularly if it’s a daylight exterior and there’s a limit on the amount of time you have and what times you can shoot. I actually like to start the day off with a few easy shots anyway just to have people hopping. Because if they’re standing around waiting for me to rehearse a whole scene and we don’t get a shot off until 10:30 on a day when we showed up at 7:00, there’s such a dip in morale. But even if you’re simply shooting an insert of someone signing a check, if you get a shot off by 7:30, there’s just something magical that occurs and everybody goes, ‘Okay, we’ve done something today.’ But it’s all just about trying to buy a kind of comfort zone for the performers and whatever works for them. If they’re not good until 9:00 a.m., we’ll figure out a way to do that. I never judge performers’ requests like that as somehow being too demanding, because if it helps the film, it’s going to help all of us.

Q: Did you enjoy using special effects on the Austin Powers films?

A: We had something like 500 shots on Austin 3—the submarine, the moon base, and the space needle turned into the Star Wars headquarters. Visual effects had already advanced enough that for the little amount of money we had we could make them pretty convincing and plausible within a comedic realm. My visual effects guy, Dave Johnson, who’s done them on all my films, is very fast, thinks like a director, and pulls off these shots without having to rob a bank. And that was really fun.

Q: You’ve done a number of sequels. Is it hard to maintain the initial inspiration?

A: I think there’s probably a prejudice about sequels that gives people the sense that they’re made just for the studios. But I love doing the sequels because you get to take the characters further. The second Austin Powers, The Spy Who Shagged Me, was my favorite of the three films. I liked all three of them, but in the second one we got to do Mini-Me, we got to invent this crazy idea of evil distilled to pint-sized form and have Dr. Evil’s empire be at Starbucks and do really adventurous things because we had the license of the first film. We were just happy to get to take those concepts further and be even more absurdist and Python-esque in some ways. It was pure joy.

SCARY: In his mind, Roach thought Robert De Niro could kill him on

SCARY: In his mind, Roach thought Robert De Niro could kill him on

Meet the Fockers. (Photo Credit: Tracy Bennett/Universal Pictures)

Q: You tend to work with high-profile talent—Robert De Niro, Barbra Streisand, Dustin Hoffman—is it true that you ask each actor how they like to be directed?

A: I guess it’s partly out of my own insecurity that I won’t have the right magic thing to say to the actor. But I also think that if a certain approach works for a performer and it doesn’t cost me anything to adjust my approach, why not find out what works for them, what’s worked in the past, and especially what things haven’t worked? For example, Tom Wilkinson on Recount needed so little, if I had just said, ‘Can we do it again faster?’ it would have been far better than this long, overly verbose direction I gave him. Other actors, like Dustin Hoffman, love to talk about the character, the moment. I asked him in preproduction: ‘You’ve worked with all the great directors in the whole world, what works best for you?’ He explained that sometimes he likes to talk things through and it’s just part of his process. If I didn’t know that in advance, I might have been less patient with it. But because we’d had that discussion, everything was cool.

Q: It’s easy to imagine a scenario in which one actor needs lots of attention while, in the same shot, another actor is fine without it.

A: Oh, sure, sometimes actors need two completely different things. Sometimes it’s a make or break decision which actor to go with first. You have to make a split-second call, and it’s not always the case that the same actor will want the same thing every day. De Niro was like this, actually. There were some days when he’d just be completely ready to go on a particular thing and I’d know to shoot him first. He’d be so good if I got it when I knew he was there. But if I waited until later in the afternoon he might not be as good. Other days, I could tell he’d had stuff that he’d been dealing with overnight, and the scene wasn’t going to be that readily available to him until later in the day. If I made the wrong call and shot him first on a day when he wasn’t ready, it could take two days of shooting instead of one.

Q: What was your first day of shooting like with De Niro on Meet the Parents?

A: I showed up the first day and got a little bit lost in the blocking with De Niro, Ben Stiller, Blythe Danner, and Teri Polo. It was the scene when they get out of the car, and Ben tries to hug Blythe and De Niro and it’s a really awkward moment. I had just started working with the DP and while I’d been off rehearsing with the actors there was a whole bunch of dolly track laid down. We just weren’t in sync at all. Somehow I started into the scene instead of trusting my instincts and doing it the way I thought it should be done. I thought we’ve already invested all this setup [time] so I went ahead with it. I remember it took all the courage I could muster to say, ‘I’ve made a mistake. Take all the track away. We’re going to reblock and start over.’ Well, that was 3:00 in the afternoon on the first day of the shoot, so we were a day behind. Right away the studio people flew out and it was a big deal not to make that day.

PRACTICE: Roach helped Dustin Hoffman stretch as an actor on

PRACTICE: Roach helped Dustin Hoffman stretch as an actor on

Meet the Fockers. (Photo Credit: BFI)

Q: That must have been a hard thing to do.

A: They always say one of the hardest things is knowing when to say ‘Cut. Print. Moving on,’ and that’s true, but it’s perhaps harder to say ‘I’ve completely blown this setup, and we can keep shooting and make our schedule and budget, but we won’t have a good scene and it’s a crucial one. So I’m hereby taking the rap for blowing it, but now we’re going to start over and do it right.’ On the first day of a shoot there’s the anxiety that goes with that, and I was also very anxious because it was Robert De Niro. The anxiousness you see in Ben Stiller throughout that entire film is definitely related to how I felt as his alter ego. In my mind, De Niro could kill me. In my mind, he was an impatient, intolerant, Oscar-winning movie star who’d worked with far greater directors. But the opposite was true: he was extremely patient and actually very constructive and helpful. He was very cool.

Q: Streisand and Hoffman joined the cast for Meet the Fockers. Were you anxious about that?

A: We jumped into making Fockers with only a partial script, and my stress on that one was having all these Oscar-winning actors in one place and wondering what was going to happen, and me having to be the leader who knows what’s going to happen, but who’s realized there were so many unanswered questions about what the movie was going to be like when finally finished.

Q: The scene where they are all having dinner seems very natural. What did the actors bring to the table?

A: They all had ideas and wanted to try stuff. Barbra had this idea she would start drinking wine and get increasingly tipsy, which wasn’t in the script. I brought her into the cutting room during the end of postproduction, and by then I’d drifted toward the drunk Barbra version but she remembered a couple of takes funnier than the ones I found in the 88,000 feet and helped me find them. Dustin would always come in to the day’s work with a page on a legal pad reworking the whole scene, and it was always a little daunting because I’d look at it and go, ‘Oh God, new lines for Barbra, new lines for Bob De Niro...’ From time to time there were great lines, but I’d often have to say ‘Dustin, I can’t use this hunk of stuff,’ and he’d go, ‘OK, OK’ and still try to work them in.

Q: You shot 88,000 feet for that dinner scene?

A: We had 1,000-foot magazines so you only got 11 minutes of shooting, but as soon as you said ‘Cut!’ the entire crew came in like a NASCAR pit team and it would be 20-30 minutes before you’d get them back in place. So there was no cutting until we ran out of film, I would just turn on the magazines. It was an expensive way to shoot. It’s not a great way to make a movie, but in this case it was the only way to make that movie and it was the best way because I’d get some energy and liveliness by yelling, ‘Don’t cut, don’t cut, go back to this part halfway into the scene and I’ll fast forward!’ People who came onto that set must have thought it was the most disorganized thing ever. I imagine they’d say that about a lot of my shoots, but there’s a method to it. I have to unleash the chaos enough and then just keep focused on the little bits. If you snip away all the chaos, it seems incredibly tight.

Q: What kind of camera setups do you like to use?

A: Some comedy directors actually shoot opposing angles with multiple cameras, so you’re shooting at one actor over the other actor’s shoulders and then the opposing shot of the other actor. I don’t usually do that, maybe once or twice. What I do is, for instance, on a dinner scene, have multiple cameras all shooting the same direction, usually with a main medium shot that will cover most of the comedy, but then also a close-up camera. I rarely do another take exactly the same way. So I’ll ask the camera to move in a little bit or move to the side. I’ll try to vary it so that I’m always getting something a little different.

Q: Does that goes back to what you were saying earlier about the importance of the crew being on its toes?

A: Yeah, I’m sort of marching in which requires a nimble crew because then it’s easy to say, ‘Cut. Print. Go again,’ and keep everything where it is. But to say, ‘Cut. Print. Camera A, scooch in; Camera B, slide to the left. And Action,’ and they’d have to be ready in that amount of time. The focus guys are checking the focus while I’m saying, ‘Roll sound,’ and they’re moving the camera. The grips have to be nimble because I don’t want to lose the momentum of resetting and calling it a new setup, but I also have to get a new shot. I can’t afford to just keep doing the same thing over and over because, editorially, I always appreciate having a little variety. And as the scene evolves, the actors get more comfortable with it. Typically at that point I’m going, ‘Start close, move back,’ but then I’ll start working back in so that, as the nuance gets there, the cameras are finding it in closer and closer shots.

ELECTION COVERAGE: Roach prepares to shoot a scene with Kevin

ELECTION COVERAGE: Roach prepares to shoot a scene with Kevin

Spacey in Recount. (Photo Credit: HBO Films/Courtesy of Everett)

Q: Some directors don’t like test screenings, but you hold multiple previews and nearly a dozen less formal screenings. How do they inform your final cut?

A: We do around eight or nine screenings for friends and family members before starting the official previews, where we invite around 100 people who we can trust not to go onto the Internet right way. These days, preview is review, and whatever goes on to preview is going to be on Ain’t It Cool News by the following morning. We’ve solved that by being so rigorous at our friends and family screenings. They’re really kind of fun, because I get up and run the Q&A survey sessions where I ask the audience what they liked, what didn’t work, what things were confusing. What’s great is that you can tell how a comedy plays by listening to where the audience laughs, so we record the whole screening and use it in the editing room later on. We learned lots of important things, like in Meet the Parents the audience told us they felt Teri Polo’s character was too rough on Ben’s character once they got to her parents’ house which made her unlikable, lowering the stakes for the whole film. The other thing was that a song De Niro sang at the end for the reception just didn’t work.

Q: I read somewhere that Steven Spielberg, who appeared in the opening sequence of the third Austin Powers, gave you some feedback on the set. What was that about?

A: That was one of the great days of my directing career because we shot Tom Cruise, Gwyneth Paltrow, Kevin Spacey, Danny DeVito and Steven Spielberg all in an eight-hour shoot day with a lunch break in the middle. While I was shooting the Tom Cruise moment there was Spacey as Dr. Evil and you hear him go, ‘Ooo ha ha,’ or something and Gwyneth and Tom both turn at the same time and look ahead. It was a nice enough shot, but someone came up and said, ‘Steven has a note.’ And I said, ‘Oh, cool. What’s the note?’ He said, ‘What if there was a little wind on the shot?’ So I rolled an E-Fan up there and it made a big difference. Then, a year or two later he came onto the set during Meet the Fockers because he’s a friend of Barbra’s and DreamWorks was involved in the franchise. It was the scene in which she’s talking about Ben’s sex life with Teri, and it was going pretty well, but when Steven came and Barbra saw him and he waved, she just came to life. I was so grateful that he was there because just having him on the set, everybody perked up a little bit and it was great. It’s always cool to have Steven Spielberg show up on your set. Even if he has notes.

Q: Do you like to get feedback from other directors?

A: Directing movies is a very weird experience, and it’s rare that you get to share the experience with someone else who has actually done it. Not long ago, I was talking to Ron Howard about starting a kind of monthly support group or salon for directors, where we could just go out to dinner and share our experiences in a constructive manner. Then it struck me: the DGA already provides that environment.

Q: How did directing dramas such as Mystery, Alaska and Recount benefit from your work in comedy, and vice versa?

A: Dramas and comedies depend to some extent on suspense—setting up a predicament, creating a collision course for characters, establishing an expectation and then exceeding that expectation moment to moment. Particularly in comedy you have to keep topping yourself as you go along. But it’s very important in suspense—Hitchcock does this over and over—to realize that surprise is not as much fun as giving the audience a chance to actually form a set of expectations, and then sort of riff off of what they expect and delight them by exceeding their expectations or turn off what they would expect.

Q: Do you work differently in dramas than comedies?

A: The big similarity is in how I cast. In comedies I cast actors who are capable of doing both what’s scripted and improvising. In drama I also cast people who can do both, who can stick to the script but also could go off it when required to add another edge of spontaneity to give the audience a sense that it’s not all quite so contrived and controlled. Even though Recount was a full-on drama, I almost exclusively cast people who are completely capable of doing comedy: Kevin Spacey, Denis Leary, Ed Begley Jr., and Bob Balaban. Laura Dern is one of the funnier people around and her sense of irony in the David Lynch movies is just fantastic. That was a real important one because I didn’t want the funny version of Katherine Harris, even though it was so tempting to do that. For me it was casting people who could have an eye toward the entertainment value even though it was meant to be a very dramatic, very historical piece.

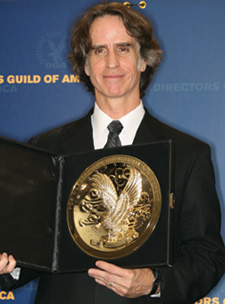

DGA AWARDS: The director picks up his DGA Award for

DGA AWARDS: The director picks up his DGA Award for

Recount. (Credit: Joe Coomber/DGA Archives)

Q: Recount was your first made for TV movie. How would you compare that experience with your background in features?

A: It was just a whole different pace which kept it lively. I took it on knowing that it was going to be a 40-day shoot and that I had to accomplish a seemingly epic number of scenes, something like 200 scenes and 100 speaking parts. Some days were eight scenes, and I don’t think I had ever shot more than three in a day before, and usually it was more like one scene over two days. I knew I’d have to have multiple cameras and do fewer run-throughs and it would seem like I was getting a lot of material, but actually I shot very little film just because there wasn’t time. I was a little nervous about what it would be like to say ‘Cut. Print, Run! Run to the next set. Run!’ Thankfully, [the cast] were all ahead of me. They would cut, go right to the next location, everyone knew what to do, and it was a great example for me of how you can keep the energy on a set by just moving and getting a lot done. Don’t do too many takes. Don’t second-guess so much. If you’ve got a good script, trust the script. Shoot it, get it, don’t do any more and get on to the next thing. As a result, it was a completely different experience and a fantastic one.

Q: Mike Myers says your real talent lies in your “charmth”—charm and warmth. Does it pay to be a nice guy director or is it better to be a tyrant?

A: I don’t know. Directing is always, to some extent, getting a lot of people to do something they don’t want to do at the moment or, at best, to do more of what they’re doing even if they don’t want to. And sometimes there is a kind of diplomacy involved. I suppose I could be more efficient if I was more dictatorial because I could just say, ‘I don’t have time to talk about this anymore, we’re just doing it. Everybody here we go, and Action!’ But I don’t think that’s good for comedy. I do think actors need to feel like it’s play. It’s almost impossible to be funny when it feels like work, so I hide my pressure from the actors. If we’re way behind schedule I never show that. I’ll just remind myself that we can make the day, or we can make a great scene.

Q: To borrow a phrase from Austin Powers, a comedy’s mojo comes from the laughs it gets. So how would you rate the different kind of laughs you need for successful comedy?

A: There’s that moment in Meet the Parents when the urn fell. Or in Borat when Sacha and his manager are wrestling in the nude. At one Borat screening, people were running down to the screen and then running back, high-fiving everybody. It looked like a tent revival, people were howling, almost speaking in tongues. That’s a triple-A laugh. Then there’s just the really big A-laugh—when people are rocking in their seats while connecting to deeper truths. If they’re just laughing and not really moving but just going ‘Ha, ha that’s really funny,’ then that’s a B-laugh. There’s a whole range of sub-sub B laughs that you still like, but in a broad comedy you’re always trying to build the number of A and B laughs per minute because you’re delivering a magic carpet experience where people are laughing hard and often. If audiences drop their laughter, it’s fine for an emotional or character reason, but they can’t do it for long because getting the wind up under the carpet again is just too difficult. Audiences are demanding—if they come to a broad comedy, they want to be laughing the whole time.