BY LARRY CHARLES

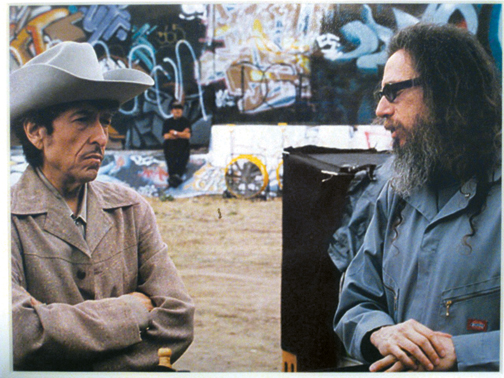

IS IT ROLLING, BOB?: Bob Dylan and Larry Charles spent a lot of time

IS IT ROLLING, BOB?: Bob Dylan and Larry Charles spent a lot of time

discussing Bob's wardrobe for Masked and Annonymous.

There I was, the first day of filming Masked and Anonymous with Bob Dylan. The budget was tight. The schedule was short. I was juggling major stars like Jeff Bridges and John Goodman, Jessica Lange and Penélope Cruz, Mickey Rourke and Val Kilmer, Luke Wilson and Ed Harris, Christian Slater and Chris Penn, Angela Bassett and Cheech Marin.

And it was my first movie. The first shot of my first movie. Bob and I had spent a lot of time discussing his wardrobe. We had decided on a sort of 1950s Mexican cowboy motif, elegant and dandified, but rugged. Buñuel meets Nudie. A matching brown silk cowboy shirt and flared trousers with elaborate piping, hat, boots and scarf. Bob emerged from his trailer that was perched in the center of a vast beehive of activity in a downtown L.A. parking lot next to our derelict location, wearing the agreed-upon wardrobe. But much of it was covered by a jacket. A very cool vintage jacket, but nonetheless, one we hadn’t ever discussed. One which I had never seen. Eager to get started I said, “Oh, that’s a nice jacket, take it off so we can begin.”

He said no, he wanted to wear it for the movie. The whole movie. “No problem,” I said, “We’ll get a fabric swatch and make a couple of doubles for back-up.” After all, there was fighting and killing and mayhem on the agenda.

That’s when his stylist, an imperious Brit, delivered the news to me with a bit too much sadistic glee. This is an antique jacket. They don’t make this fabric anymore. It can’t be reproduced. Suddenly, as I had learned in Bob’s universe, things had changed.

So the issue was settled. Bob would wear the jacket and I would secretly become the keeper of the jacket. After that, the whole movie became about the jacket. More important than the celebrated actors, the script, the cinematography. Even Bob! I could replace Bob like Ed Wood replaced Bela Lugosi with his dentist after he died on Plan 9 from Outer Space. But I could not replace that jacket. Day in, day out, the jacket became my obsession. Bob eating fried chicken in the jacket. Take it away! Bob drinking coffee in the jacket. Take it away! Bob smoking a cigar in the jacket! Put it out! I had to jacket-proof the whole set.

I interpreted everything through the fabric of the jacket. How will the jacket respond to this scene? Will it get dusty or dirty? Will it get stained or torn? If it does, I will literally have to shut down the production. I could shoot around Bob. I could not shoot around that jacket.

We got ready for our first shot. The scene was set inside an abandoned bank building downtown made to look like a post-apocalyptic bus station. It didn’t require a lot of art direction. It came as is. Camera-ready. Bob has an encounter with a seductive lady in red (Laura Harring), who may or may not have shared a past with him. The shot was rather elaborate. A crane shot to include the entirety of the bus station with its ending mark, a tight two-shot of Bob and the lady in red.

As we rehearsed the move, I began to hear music in my headphones. I started asking people if they heard it too and everyone said yes. It was faint, but it was very present. I assumed it was somebody playing a boombox outside the building and someone ran out to check, but there was no one out there. Yet, the music persisted. At that moment, I looked at the monitor and saw Bob on-screen, standing awkwardly, waiting, fidgeting at the makeshift ticket counter as extras loitered around him. I thought, this is the first shot of the first day and we have this weird problem and he’s getting impatient. He’s not used to this. I’d better go talk to him.

So I begin to cross the bus station in his direction and as I do, the music grows louder and louder. And as I walk toward him, I realize the music is coming from him. The music is literally emanating from him. And I thought, wow! Bob Dylan really is a genius. He literally exudes music.

Then I see that he has an earwig in his ear and I realize the music is coming out of that earpiece. And I say, “What’s that?”

And he says, (and you have to imagine Bob Dylan saying this) “Tupelo.”

And I say, “Not the song. The thing in your ear.”

He proceeds to tell me that Johnny Depp recommended it to him. There’s a DJ in the parking lot. Johnny Depp’s DJ. He’s in some kind of teepee or a tent and he’s pumping music to Bob during the scene. I had noticed when he rehearsed the scene with Laura, that he seemed barely able to hear her and talked at a strangely loud volume. It seemed a little weird, but I thought it was a Bob choice. It wouldn’t have been the first. I now realized it was the music blasting in his head.

I told him that he might have misinterpreted what Johnny had told him. That I found it hard to believe that he would have suggested that he play loud music during the scenes. Maybe between scenes.

And Bob was like, “No. During.”

I hit the ropes and bounced back. “Look. It doesn’t work on numerous levels. You can’t hear what the other person is saying. You can’t hear your own voice. The music is all over the soundtrack so we could never get rid of it. And even if we thought it was appropriate to use it for background music, it would cost us a fortune, which we don’t have.”

Amazingly, common sense prevailed. I was able to focus again on the jacket.

After that, the movie seemed to be going great. But I realized how much my feelings were colored by the condition of the jacket. I began to wonder if other filmmakers had this problem. Did Roman Polanski brood on set about Jack Nicholson’s band-aid coming off in Chinatown?

So we make it to the last day of shooting and you would have thought I’d be feeling pretty cocky by then. The jacket’s magical powers worthy of Joseph’s in the Bible. But although I didn’t betray my emotions to the cast and crew, I lived in mortal dread of the film’s final day. A 22-hour day that would end in the violent death of the character played by Jeff Bridges.

More importantly, before he died, he and Bob had to fight. The jacket was going to be in a fight. The fight was about ontology and poetics, art and history, reality and illusion, truth and perception, which ends in Jeff being bashed to death by Luke Wilson with a mystical guitar. Like El Kabong on a psychotic rampage.

Now Jeff Bridges is a wonderful man. Warm, generous, genuine and perhaps more knowledgeable about every aspect of filmmaking than anyone I’ve ever met. But he’s also the Big Lebowski. This dude is big.

And Bob is on the diminutive side. And although there were stuntmen and rehearsals, ultimately Jeff and Bob had to fight. At one point, Jeff had to push Bob. I had them walk through the camera blocking more for the cameramen and the stuntmen than for the actors. I had them save the action for when the cameras were rolling. I knew the jacket only had one take left in it. I had tempted fate. I had teased destiny. I had fucked with eternity and now I was about to pay the price.

I hate yelling ‘Action!’ but never more than I did that fateful day.

Jeff, completely immersed in the scene—angry, bitter, volatile, damaged—comes at Bob with all his fury and force, the way a defensive lineman would rush an Eastern European punter in an NFL game. He pushed Bob with all his might. Bob and his magic jacket lifted off the ground. It must have only been a few seconds, but for me, it seemed like forever. I watched Bob hurdle through space, the pattern on the jacket blending and changing like a kaleidoscope.

He hit the ground like he’d been dropped from a plane without a parachute. Thudding along the concrete. He somersaulted backward but amazingly landed on his feet. I yelled ‘Cut!’ and raced toward the jacket. The human inside it was Bob Dylan. And yet, I didn’t care. He seemed okay. Astonishingly, so did the jacket.

I started to think that maybe Bob was like Superman. The jacket was made from the blanket his parents wrapped him in when they sent him to Earth before their planet exploded. Knowing Bob, it wouldn’t surprise me.

I have often described Masked and Anonymous as an apocalyptic sci-fi spaghetti Western musical comedy. And it is all of those things and more. Like for instance, the story of a jacket.