BY GARY GIDDINS

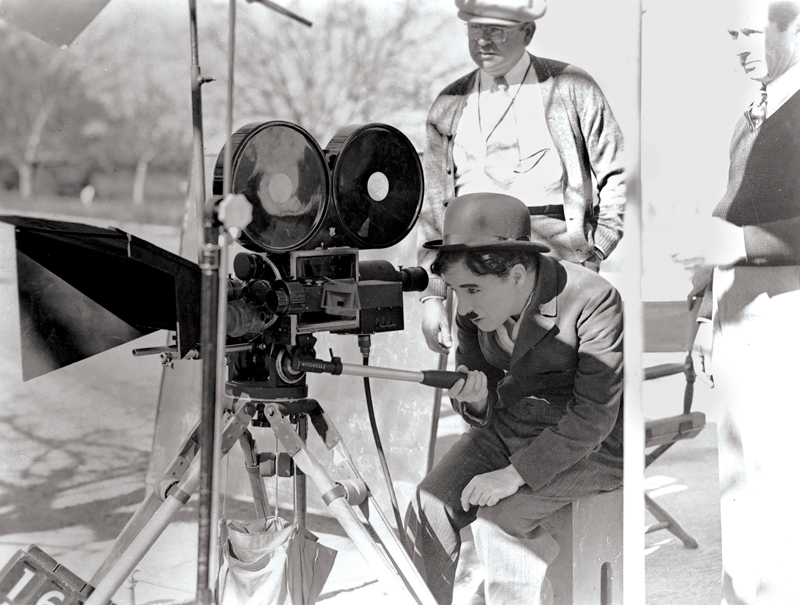

Chaplin on the set of The Gold Rush (1925). (Credit: BFI)

Chaplin on the set of The Gold Rush (1925). (Credit: BFI)

No popular artist since Shakespeare achieved greater universal renown than Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (1889-1977), primarily for his enduring alter ego, the Tramp: the relentlessly caricatured and mimicked little man with big sensitive eyes, unruly hair, and square mustache, dressed in frayed black derby and tailcoat, ballooning trousers and oversized shoes, twirling a pliant cane as he saunters, herky-jerky and splayfooted, down a dirt road toward an unpromising horizon. As the centenary of his first one-reel shorts approaches (2014), Chaplin seems safely installed in the pantheon of immortals. Earlier this year, Warner Bros. and the French company MK2, who had released magnificent DVDs of the ten feature films and seven shorter pictures Chaplin made between 1918 and 1959, took out a full-page ad out in Variety to boast of 3.5 million in sales since 2004. Yet Chaplin's legacy increasingly belongs to the ranks of the cinematically educated and students who are most likely to encounter him in the classroom as a director first and foremost.

For much of his career and for years after, Chaplin's brilliance as a performer helped foster the canard that he wasn't really an innovative filmmaker, but "merely" an uncanny performer who did little more than point and shoot at himself. Yet it's hard to watch his films today without recognizing that had Chaplin not been a director of sublime gifts, the great comedian, for all his improvisational élan and dazzling balletic-athletic virtuosity, could not have sustained interest over so long a period. Of the leading silent clowns, those who crafted the films that framed their personae—Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd—or had the aid of great comic directors—Frank Capra for Harry Langdon, Leo McCarey for Laurel and Hardy—are the ones who survived as distinct entities beyond the slapstick mill that produced them. And of them, only Chaplin, the perfectionist who controlled every aspect of the filmmaking process, flourished well into the sound era, making profoundly different kinds of movies that reflected the period in which they were made.

Today, a Chaplin education is easily acquired: most of his major work is available in meticulously restored DVD editions, a phenomenon that cannot but astonish those of us who had to put up for decades with faded, spliced, and utterly botched prints—when we could see them at all. Only after his death, when Chaplin's personal collection was accessed, did his films re-emerge with their pristine beauty intact. All that's missing is his apprenticeship with Mack Sennett's Keystone Film Company (35 films made in 1914, the year when he conceived but rarely played the Tramp) and the 1967 flop, A Countess from Hong Kong. The 14 shorts he wrote and directed in 1915 for Essanay, establishing him as a universal phenomenon, are available on three separate volumes from Image Entertainment. The 12 more intricate and personal short-form gems he made for Mutual in 1916-1917, in fulfillment of the most lucrative contract in cinema history to that time, are collected by Image in a four-disc set, The Chaplin Mutual Comedies. And as noted, the masterworks made for First National, United Artists, and Charles Chaplin Productions have been assembled by MK2 and distributed here by Warner Bros. in two boxed sets, The Chaplin Collection, or ten separate volumes, most with second discs containing ancillary material.

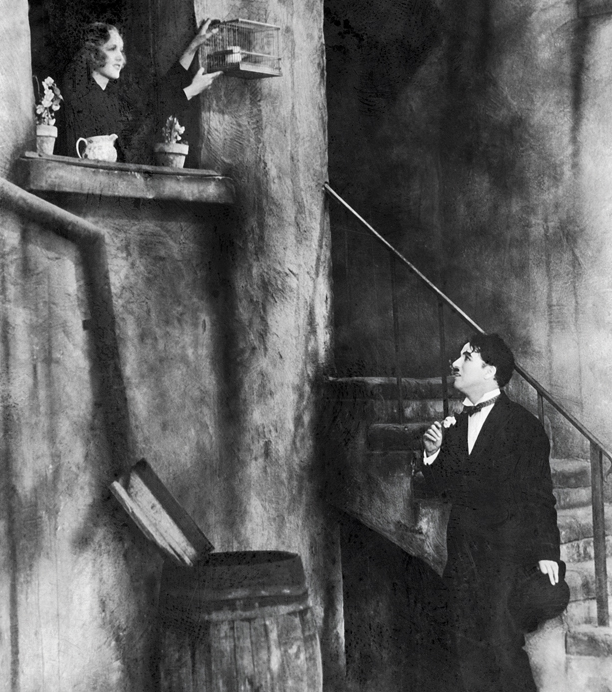

THE KID (1921) (Credit: Everett Collection, Inc.)

THE KID (1921) (Credit: Everett Collection, Inc.)

Chaplin's archive, with its countless outtakes, incompleted projects, and home movies, proved to be the equivalent of a novelist's workbook, showing how he developed films after months of improvisation (more than two years in the case of City Lights), discarding bits that lesser artists would have pointed to with pride. Chaplin's private stash provided insights that eluded his biographers. Two essential Chaplin documentaries make use of this material: Kevin Brownlow and David Gill's three-part 1983 Thames TV series, Unknown Chaplin (A&E) and Richard Schickel's 2003 film Charlie: The Life and Art of Charles Chaplin (MK2/Warner Bros., also included in the boxed sets). The former reveals, camera-slate-by-camera-slate, how he devised the last three Mutual shorts and overcame various obstacles (some of his own making) in creating his early feature films. The latter, a poignant critical and biographical portrait, chronicles his artistic rise, his humiliating fall from public grace, and reveals, for the first time, home movies of the secluded Swiss Eden that Chaplin enjoyed in his last years.

Chaplin's directorial genius first became indisputably clear with The Kid in 1921. Here, he invented a new kind of film that balanced farce and drama, slapstick and tears, triumph and anguish. He was warned that he was courting disaster, that people came to see the Tramp to laugh, not to cry, and that if he made them cry, how could he get them to turnabout and laugh again? He concocted a customary plot for The Kid. The Tramp, saddled with an orphan, played by the implausibly adorable and talented six-year-old Jackie Coogan, finds love and purpose by taking responsibility for the boy, battling social guardians to keep him. For seven reels, incidents of astonishing, resourceful comic irreverence (the Tramp teaches the kid various scams) are interrupted by scenes of wracking pathos.

Chaplin understood as well as D. W. Griffith that the hallmarks of melodrama—chases, sentimentality, and happy endings, held in low repute by serious artists—could be fine-tuned as the basis for empowering cinematic expression. Chaplin, however, could do what Griffith couldn't: check melodrama with ingenious comedy. And he could do what the slapstick king Mack Sennett couldn't: check the comedy with affecting drama. If Chaplin's greatness as director/writer/actor/producer/editor/composer can be summed up in one word, it might be balance. He peerlessly weighs the scales of laughter and tears, while avoiding gross sentimentality and routine pratfalls, never more effectively than in his masterpiece, City Lights (1931). A mostly silent film released four years after the synchronized dialogue in The Jazz Singer, it was seen by most as another folly.

In City Lights, Chaplin effortlessly switches gears between inspired black comedy (involving attempted suicide, boxing, and jail) and the heartbreaking glare of reality: The Tramp loves a blind flower girl and resolves to restore her sight by financing an operation; the girl mistakes the Tramp for a millionaire and loves him as long as she is blind and imagines him as a generous, romantic benefactor. The Tramp's success is his undoing. Consequently, one of the screen's supreme comedies sends the audience home dabbing its eyes.

Chaplin believed that comedy and pathos must always stem from credible, human logic. In Unknown Chaplin, we see him driving himself, his crew, and especially his leading lady Virginia Cherrill, crazy over one crucial scene in City Lights, lasting only seconds in the final cut. The problem is to find a reason for the flower girl to mistake the Tramp for a rich man. After weeks of improvisation, meditation, tirades, and frustration, he found the solution in the illusion of sound. Immediately after selling the Tramp a flower, she hears a limousine pull away from the curb and assumes it's his. The entire film is built on such confusions, but Chaplin the director has the mixture completely under control, the audience always bending emotionally to his will.

CITY LIGHTS (1931) (Credit: Everett Collection, Inc.)

CITY LIGHTS (1931) (Credit: Everett Collection, Inc.)

Between The Kid and City Lights, Chaplin made three features that showed how accomplished a filmmaker he had become. His powerful yet neglected drama A Woman of Paris (1923) failed at the box office because Chaplin wasn't in it (other than a bit part), yet continues to enthrall in its meticulously detailed, daring telling of the familiar tale of innocence hammered by worldly sophistication. A good girl (Edna Purviance) is corrupted through the influence of a supercilious playboy (Adolphe Menjou), but in the end she isn't so good, he isn't so bad, and the pure-hearted artist she loves is a weakling and prig. In this film, Chaplin perfected a much-imitated technique of starting with a wide shot and then cutting into a scene. He compensated for the economic impossibility of having a railroad at his disposal by giving the impression of a train leaving the station through the use of shadows.

He regained his audience with two tours de force, The Gold Rush (1925) and The Circus (1928), each marking another stage in perfecting his balance between farce and emotional terror, and between impressive wide shots and intimate close-ups. In The Gold Rush, Chaplin initially took his crew into the wilds to get mountainous location shots, but the most famous scenes in the film are simply shot as the Tramp sits at a small table: turning two bread rolls into a high-kicking chorus line, and filleting his shoes as though they were a trout dinner. The Circus has a peerless edit near the beginning, as Chaplin establishes twin conflicts between the Tramp and one cop and a thief and another cop. After switching from one duo to the other and back, he suddenly cuts—the timing is impeccable—to a wide shot as the Tramp and thief converge on the midway, running hysterically toward the camera.

Beginning with Modern Times in 1936, the social satire that ran throughout his work, with its accent on petty cruelties and class divisions, became more brazen. There are unforgettable moments, as the Tramp battles machinery, dances, inadvertently leads a worker's demonstration, and heads toward the horizon with Paulette Goddard in hand. Yet Modern Times belongs to the later Chaplin, when he finally capitulated to sound, upsetting the incomparable balance of the silent masterworks. Language brought out the insecurities of a childhood spent in Edwardian poverty, shadowed by the workhouse and the madhouse. Aiming for the impertinent glow of Bernard Shaw, he often settled for moralizing guff, self-pity, and sentimentality. Still, there are flashes of genius, particularly when he worked with other gifted comics—Jack Oakie in The Great Dictator, Martha Raye in Monsieur Verdoux (1947), Buster Keaton in Limelight (1952)—or alone as in the balloon-globe ballet in The Great Dictator, which is surprisingly beautiful, as the globe rises in the air as if borne on its own current.

THE GOLD RUSH (1925) (Credit: BFI)

THE GOLD RUSH (1925) (Credit: BFI)

There can never again be a director like Chaplin, who could afford to sit on a chair, head in hands, for hours, weeks, months, trying to think of an idea as the clock ticked, the cast and crew played cards or stayed home, and the costs skyrocketed. Nor could a director survive today who insisted on turning his actors into mimics.

In the years when he mastered his art at Essanay and Mutual, Chaplin surrounded himself with pros, veterans of vaudeville and the Sennett mill. But in his greatest silent films, he often preferred—especially in his leading ladies—amateurs, "virgin" actors who would do his precise bidding. No less then other great filmmakers, he made movies that reflected the vision of a single artist: the director as complete and uncompromising master of his domain.