BY JEANNE MCDOWELL

CHICKEN LITTLE: Stuart Gillard used unconventional methods

CHICKEN LITTLE: Stuart Gillard used unconventional methods

to direct his 7-year-old star in Hatching Pete.

When 7-year-old Aramis Knight had to do an emotional scene for the upcoming Disney Channel movie Hatching Pete, Stuart Gillard knew just how to direct the pint-size actor. He created a quiet, non-threatening environment on the set and alerted the crew to pretend that it was just a rehearsal. "I rolled the cameras without Aramis knowing," says Gillard. "I started to engage him in conversation talking about the scenes. We casually went through the dialogue a few times. All the while he didn't know he was being filmed. At the end, I told him it was a great cut and that we were going to do it for real. But I didn't tell him that until I knew I had a good performance in the can."

Deception? Maybe. But in directing children, unconventional ploys are sometimes as necessary to the end product as the right camera angles and delivery of lines. Unlike adults, child actors–from the very young ones to teenagers–are, after all, kids. That means they tend to freeze up and become shy in front of the camera and crew and get cranky if they're tired or hungry. "At the end of the day you feel like you've been a parent for 12 hours," jokes Gillard, whose credits include the Disney Channel's original movies Twitches (2005) and Twitches Too (2007) and a host of episodic tween shows. "I know all the tricks. But you also need a sharp crew. You can't have people driving through a shot when you're rolling the camera. I use the phrase "Code Red" to indicate that I'm rolling and the kid doesn't know." Adds 1980s Wonder Years star Fred Savage, who grew up to become a director (Wizards of Waverly Place, Aliens in America) and often works on programming for children and teens: "One thing I've learned from working with kids is that you want to make them comfortable. They're incredibly sensitive and attuned to the mood on the set so you take great pains to make things positive."

By all accounts, it's worth it. Over the past decade, as cable channels like ABC Family, the Disney Channel and Nickelodeon have proliferated, the demand for non-adult programming has risen, which translates into booming business for the cadre of directors who specialize in working with young actors. The mind-boggling success of High School Musical and the Cheetah Girls franchise has shown programming executives the profit potential in the tween and teen audience. Hence, more original movies are being green-lighted for TV with bigger budgets and production values. The Cheetah Girls: One World, for example, the third and latest in the successful Disney franchise, directed by Paul Hoen, commanded a $7.5 million budget and was filmed over three months in India. (It airs in August.)

Child-actor turned director Fred Savage works on an episode of

Child-actor turned director Fred Savage works on an episode of

Wizards of Waverly Place.

But working with young actors is a different ballgame than directing adults. Directors must deal with fierce time constraints, stringent labor laws, stage parents and young nervous systems that can be more fragile than the most insecure Hollywood ego. Under federal law, actors under 16 are permitted to work on set only nine hours a day, which often isn't enough time by television production standards. Of those nine hours, three must be spent on schooling of some kind and one additional hour is allocated for recreation. To accommodate, directors who have experience in non-adult programming are adept at being economical and planning ahead to fit the needs and legal requirements mandated for underage actors.

It typically means adhering to a strict schedule that doesn't allow for reshooting material. "You have to go in with a clear idea of what you really need for a scene," says Hoen, whose latest TV movie, The Cheetah Girls: One World, is his eighth Disney Channel original in a long career specializing in children and teen programming. "It's not like with an older actor where you let them explore a scene a little bit. Everything is done on a narrow margin. If your timing is off and you call a young actor in an hour early you're screwed because it's not like you can make that scene up at the end of the day." Some directors film with two cameras and use an adult stand-in until the very moment they actually need the child actor on camera. "Sometimes you save scenes where you see that there are other people around the child," continues Hoen. "That way you can always have more of them on camera if you need it."

There also has to be a degree of flexibility when directing children, some of whom aren't able to remember their own lines. The goal, says Hoen, who won a DGA Award in 2007 for his movie Jump In!, is to get a performance that doesn't sound stiff or appear like a caricature of a kid actor. Sometimes the best way to do that is by ignoring the script. "Early on I learned that making a child read a line a certain way is death of a performance," says Hoen. "It's more about finding the way a child would say something or how a teenager would talk in real life. You learn quickly not to be married to the script but to understand the dilemmas for the characters. But the phrasing, the dialogue and all that has to be natural. The key to getting a good performance from a kid is to find what comes naturally to that person as opposed to imposing something you think it should be."

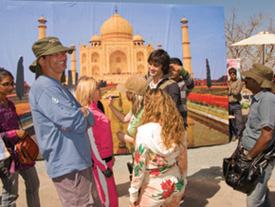

GOING GLOBAL: With budgets getting bigger, Paul Hoen shot

GOING GLOBAL: With budgets getting bigger, Paul Hoen shot

Cheetah Girls: One World on locations in India for over three

months for $7.5 million.

When Hoen directed then 14-year-old Shia LaBeouf in Tru Confessions, a 2002 television movie that bagged the actor an Access in Media Award, his goal was to make LaBeouf feel comfortable and trusting so he could deliver a convincing performance as a developmentally challenged boy. The director recalls that LaBeouf had his own idea of what he wanted the character's voice to be like. "He wanted physical affectations. I watched in the monitor as he tried different things. Suddenly there it was, something in his eyes, his attitude that worked. It's not in the way he delivered a line or slurred speech but what he brought to it from his own experience."

While this kind of willingness to let a young actor find his character is part of the creative process, much of the job directing children involves a more rigid, military-like precision and planning ahead almost every detail of how a scene is to be filmed. Gillard's strategy is to spend considerable time beforehand working with his assistant director to break down each scene and figure out the exact call times for actors. Then, he brings the underage actors in early so they wrap early in the day. "You only have a few hours of filming so you have to lay out all your shots," he says. "Usually the kids go home and then I shoot the adult actors." In Hatching Pete, Aramis Knight was in so many scenes that the director started and ended each day with a scene that didn't involve the child actor, and he filmed quickly when Aramis was on camera.

Award-winning director Duwayne Dunham, who has directed a slew of acclaimed television movies including Double Teamed (2002), and Halloweentown (1998) as well as episodes of David Lynch's decidedly adult and very grown up Twin Peaks, often brings in a body double when he's directing an underage actor and shoots over the shoulder so it looks like the character. Dunham cut his baby teeth, so to speak, on the long-running family series 7th Heaven directing the seven kid actors, the youngest of whom was 3 when the series began. Having begun his career as an editor on such blue-ribbon films as One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and Star Wars: Return of the Jedi, Dunham crossed over into non-adult programming when he realized he wanted his own young children to be able to watch and enjoy his work.

"I made a decision that I was going to try to work in age-appropriate material so my kids could grow up with them," he says. Like many directors who specialize in the child genre, Dunham started with The Disney Channel, which cultivates a farm team of young actors whom the network brings along through tween and then teen productions.

"Directors come from a multitude of backgrounds," observes Savage, who concedes that having grown up as a child actor he has a bit of an advantage. "My background allows me to come onto a set and understand how to work with children and determine very quickly what they need."

EASY DOES IT: Amy Schatz created an intimate environment before shooting

EASY DOES IT: Amy Schatz created an intimate environment before shooting

kids 5-8 on Through a Child's Eyes: September 11, 2001.

For director Amy Schatz, who works primarily with children between the ages of 5 and 8, a stint with PBS host and journalist Bill Moyers was her training ground. It served her well in that Schatz employs similar good listening techniques and a quiet calm working with young children. "I create an intimate environment. Sometimes even the gaffer is hidden," says Schatz, who has won two DGA Awards for children's programming, and directed HBO's documentary Through a Child's Eyes: September 11, 2001. Schatz sets up a small room where she talks to the children for a half-hour before filming begins and helps them get comfortable, encouraging them to draw pictures and drink juice. When the interview begins she lets them lead her in conversation. Because many of her documentaries deal with a child's perspective on gritty real-life subjects, Schatz says she's very cautious about upsetting children. On the 9/11 shoot, she didn't know how much each interview subject knew and basically tiptoed around introducing questions in a gingerly way.

But when you're directing children, even the best-laid plans can go awry. You might say that's what separates the men from the boys–literally. Dunham, who is now finishing a Disney Channel series for boys based on the K-9 Chronicles, recalls the chain reaction set off while filming the 1994 feature Little Giants. He was directing 70 little boys between the ages of 8 and 12, all of whom were wearing peewee football uniforms, helmets, pads, the works for a scene on the football field. "I used to dread it when the water person would come out," he says. "I knew what would happen. And sure enough, as soon as the first kid says, 'I've got to pee,' all 70 had to pee. There goes your scene, when 70 boys go off to the bathroom. It would take 40 minutes to get them all geared up again."

But as important as it is to handle the actors, directors must simultaneously keep in mind the point of view of their young target audience to find the right tone and hit the right notes. Gillard says directors typically gear the material for a bit older audience since kids, tween and teens watch content beyond their years. "You try to direct in such a way that you never talk down to your audience or assume that they're not able to follow complex story or emotions," he says. "In most ways, directing for children is no different than it is for adults, except with not quite as much subtlety. Kids today grow up with sophisticated imagery. So you tell the story in a very clear manner with clear emotions. You can't just have fastball action. I've always been amazed at how kids can be engaged and happy watching portions of a movie where characters are conflicted. But studios panic and think they have to keep the action moving and fast for a younger audience. That's a big mistake."

MAGIC TOUCH: Duwayne Dunham crossed over to children's programming

MAGIC TOUCH: Duwayne Dunham crossed over to children's programming

like Halloweentown so his kids could enjoy his work.

Many of the directors who specialize in shows for kids have worked in grown-up programming, and some go back and forth, but they concede that making a name in children's longform and episodic TV sometimes stigmatizes them and makes it harder to break out of the genre. "I try not to become a hack kids director," says Hoen. "Getting a DGA Award for Jump In! opened a lot of peoples' eyes as to what I do." Gillard agrees. "The problem with our business is that when you've directed 10 Disney movies some people wonder why you would want to direct an episode of 24. It's hard to get around that. So you have to get an interview and convince them to let you take on the material. But my earlier career was science fiction and horror, things my kids couldn't watch. So directing these movies allowed me to do something my own children could enjoy."

And then there are the unexpected pleasures. When Gillard was directing Hatching Pete, he wanted his young star Aramis Knight to say the line "Run, chicken, run." When the cameras were about to roll, with 500 extras hovering, the actor piped up. "I've been thinking," he told his director, "I'm saying 'Run, chicken, run,' but the chicken is in a car. Wouldn't it be better to say 'Go, chicken, go?'" Gillard agreed, and the cameras rolled.