BY LYNDON STAMBLER

(Credit: Mario Tursi/Miramax Film Corp.)

(Credit: Mario Tursi/Miramax Film Corp.)

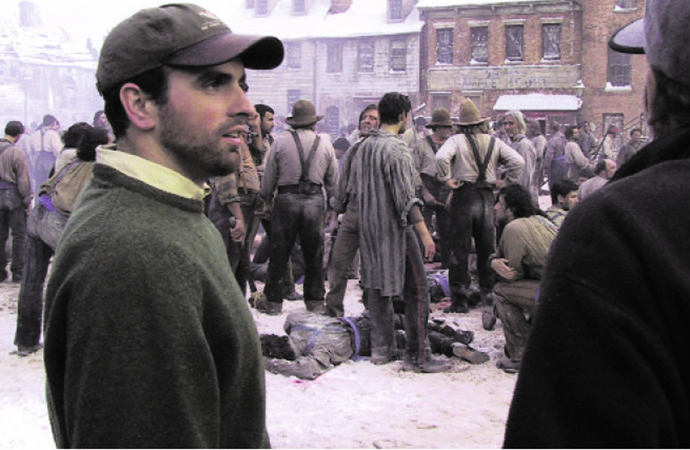

OLD TOWN: 2nd AD Chris Surgent (left) and 1st AD Joe Reidy used up to 400

extras in Rome's Cinecitta Studios to create an authentic background for

the mid-19th century draft riots in Gangs of New York. (Credit: Miramax)

The background actors in The Soloist didn't need an acting coach to get into character. On a mock Skid Row set east of downtown L.A., these extras played themselves. One woman said she liked to dance, so 2nd AD Chris Castaldi set up a boom box and she danced wildly for three hours. A man thought he was from outer space, so when Castaldi suggested that his spaceship was about to arrive, the man smiled. And it didn't take long for 1st AD Eric Heffron to see that the extra selling crack pipes in the scene would be able to repeat the same action for multiple takes.

It wasn't the burned-out cars or the debris that gave The Soloist its grittiness. It was the 350 homeless people who helped recreate the milieu where Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez (played by Robert Downey Jr.) discovers Nathaniel Ayers (Jamie Foxx), a homeless, Juilliard-trained violinist.

It was director Joe Wright's idea to use real homeless people as background actors. "Real-life, downtown L.A., 2005. That was what Joe was after," says Heffron. But Wright depended on the ADs to make it happen.

From preproduction until the day shooting wraps, creating realistic background action requires close collaboration among the director, the ADs and the department heads. The director is like the coach and the 1st AD is the quarterback. But it's the 2nd ADs who are primarily responsible for setting the background that the director envisions. They work long hours creating the"extras breakdown"–which details what the production requires–selecting the extras, and then shepherding them through hair, makeup and wardrobe. And finally they place them on set, and wait for the 1st AD and director to tweak what they've done.

Wright and the ADs, along with the background casting professional, culled the homeless from the Los Angeles Men's Project and rescue missions, consulting with advocates about which people could handle the task. Over a two-month period, The Soloist crew employed anywhere from 10 to 350 homeless extras ranging in age from 14 to 80. And the cast and crew bonded with the homeless. "They were beyond wonderful," says Castaldi, who worked closely with them.

The ADs would pick up the homeless background actors as early as 4 a.m. Wright and the costume designer looked them over to make sure they had the "Skid Row look." "In terms of the template of the film, if something was screaming orange, then we'd do a quick shift," says Heffron.

Setting background, whether it's the homeless or the 19th-century Irish immigrants in Martin Scorsese's Gangs of New York, is as important to the fabric of a film as peasants in a Brueghel painting. The characters breathe life into the movie.

"You take a city street and it's a blank canvas," says Joe Reidy, Scorsese's longtime 1st AD. "The principal characters have to live in a real world. The background action must be right."

Each film presents unique challenges. For Gangs of New York, it was a daily struggle to find redheaded extras in Southern Italy; for Sex and the City it was translating the human energy of New York to the screen; on Iron Man, director Jon Favreau relied on the ADs to find 50 extras in Southern California who looked like Afghani insurgents; in Jon Turteltaub's National Treasure: Book of Secrets, the challenge was keeping 250 background actors dry during a rainstorm.

Scorsese had wanted to make Gangs of New York for 20 years and knew that the bloody street and barroom fights were essential to create the aura of New York's underclass in the mid-19th century. Using written accounts and sketches, they built sets at Rome's Cinecittà Studios. Scorsese and Reidy discussed the backgrounds during preproduction. Second Assistant Director Chris Surgent compiled a detailed extras breakdown of the women, men and children who would be needed for the production. The more specific the breakdown, the more realistic the scene.

"It wasn't just having people walking around talking to each other, but people walking through the frame carrying a bundle of hay," Surgent says. "Some kids are running, some are stealing, some are pillaging. There's a sale going on here, an argument over there, a fight going on over there. There's real life to it."

For some scenes, they needed up to 400 background actors, but in Rome few of the extras looked Irish. For some scenes, they had to import people from the U.K. "I just remember the daily challenge of getting extras out on the set and making this world come alive," says Reidy.

In the U.S., a production normally uses an extras casting agency, but at Cinecittà, "crowd marshals" would gather the extras. Reidy, Surgent and two Italian ADs developed a system of winnowing them down, getting them organized, dressed, made up and placed on set. But even after the background actors were ready, it could take more than an hour to set up a scene.

DESERT DANGER: (left to right) 1st AD Eric Heffron, 2nd AD Michael

DESERT DANGER: (left to right) 1st AD Eric Heffron, 2nd AD Michael

Moore and 2nd 2nd AD Giselle Gurza Junco had to round up a team of 50

Afghani "insurgent" extras in L.A. for Iron Man.

"Simply telling the extras where to move and how to behave was not enough," Reidy says. "If someone was pretending to be cooking in Paradise Square or mending something, we had to work with the art department, special effects, the animal handlers. Everything had to be worked together."

Reidy and Surgent gave directions through the Italian ADs, but "half the time you weren't sure if you were getting your point across," says Surgent. "There was definitely something lost in translation."

It was essential to make sure the background didn't detract from the actors. A dance scene set in the Old Brewery starts with Jenny Everdeane (Cameron Diaz) sitting in a chair and looking at a line of men through a mirror, rejecting each one until she sees Amsterdam Vallon (Leonardo DiCaprio). Scorsese wanted the men to look blank, but he kept being distracted by one extra.

"He'd end up focusing so much on one guy and his expression that it distracted him from the task at hand," Surgent says. "By the time we were done, there were 147 of 'that guy.' The thing about Marty is he pays a lot of attention to the background, especially on the wider shots. He wants things to be as authentic as possible."

The dance required 200 background actors, including couples dancing awkwardly while holding candles. The camera pulls back from Jenny and Amsterdam to reveal dancers on the lower levels. Surgent didn't teach the extras how to dance–the Irish immigrants wouldn't have had lessons anyway–but placing the extras in the scene with the principals required synchronization.

Once the shot is set, Surgent always checks the frame on the video monitor to coordinate the background with the actors and camera movements. So that the audience could see the candles, the couples could only dance within a small area.

Another scene, the intricate draft riot sequence, which combined stunts and 400 extras, took weeks to shoot. The ADs and PAs shepherded the extras through hair, makeup and costumes to turn them into immigrants, cops, natives and union soldiers. "One day they'd be soldiers, the next day they'd be running from soldiers," says Surgent.

When union soldiers aimed their weapons at the rioters, Surgent wanted to startle the extras. In the U.S. he would have shouted "Bang!" through a megaphone. But in Italy, a prop man handed him a gun with blanks. Surgent was surprised, but held the gun behind his back and pulled the trigger. "It was very effective, but in the States you would never dream of doing that," he says.

An entirely different vision of New York was created for Sex and the City. New York was the "fifth woman" in the film, says 1st AD Bettiann Fishman. Whenever the four women venture out, they interact with people at restaurants, boutiques, or on the street.

Director Michael Patrick King told Fishman and 2nd AD Andrew Fiero exactly what he wanted. A preproduction background meeting would usually take five hours. On Sex and the City, it took three eight-hour days. "I've never had a show that was this precise for background," Fiero says. "It was more polished with hair, makeup and wardrobe than I've ever seen it."

Fiero began creating a breakdown for 2,300 background actors as soon as he got the script. He and the casting professional figured out exactly how many people they needed for each scene.

For scenes that required "specialty background," they would bring up to 100 people in for interviews with King, Fiero and producer Eric Cyphers. Fiero then met with the departments to figure out how long, for example, it would take to process hundreds of extras for the jewelry auction scene or the New Year's Eve sequence. "We set everything up in advance to get it done in time for them to be in front of the cameras," Fiero explains.

Fishman and Fiero used 700 extras for the glamorexic fashion show, one of the film's big set pieces. The sequence, shot at Steiner Studios in Brooklyn and at Bryant Park in Manhattan, took three weeks to plan and four days to shoot. In preparation, they attended three fashion shows, brought in advisers from Vogue and Fashion Week, and reviewed headshots to select models and outfits. Then they had to coordinate with all departments before filming could begin.

CITY LIFE: 2nd 2nd Andrew Fiero (right) moved 450 extras around to make it

CITY LIFE: 2nd 2nd Andrew Fiero (right) moved 450 extras around to make it

look like there were more of them in setting the audience background for the

big fasion show scene in Sex and the City, which took four days to shoot.

Among the extras, they had to set 40 photographers and 450 audience members. They moved the extras around and shot them at different angles to make it look like there were more of them. During production, Fiero says he talked to Fishman constantly: "What do you want? What do you think about this? Here's a schedule, here's the layout."

Fishman knew where the photographers should be and tweaked the audience, placing the most interesting-looking people up front to surround the stars "in a way that would not overshadow our girls but blend in."

Fiero set the background and Fishman looked it over. "Sometimes I like it and I don't even tweak it, but that's unusual," she says. "At the end of the day I end up fixing and tweaking and perfecting it. I don't just throw people in the frame for the hell of it. If we're on a quiet street, I leave it quiet. I do it based on what's real in New York City."

The methods for setting background vary from director to director. For Iron Man, Favreau gave Heffron "the vibe and we implemented," he says. Heffron storyboarded the background action for 2nd AD Michael Moore and 2nd 2nd AD Giselle Gurza Junco. "It's a big ballet," Heffron says. "I've got such quality 2nd ADs that I don't need to micromanage in their rice bowl."

An elegant scene at the Walt Disney Concert Hall featuring an inebriated Tony Stark (Downey) involved 300 extras. Heffron wasn't worried about his 2nd ADs, but he couldn't control the weather.

"On our first day of shooting at Disney Hall, the tents set up for the extras' makeup, hair and costumes were blown away by powerful Santa Ana winds," says Junco. "Thirty minutes into our background call, we had to get over 300 backgrounds ready in formal attire, but had nowhere to do it."

Luckily, they were able to move the setup into the Disney Hall cafeteria, and what normally would have taken hours, took minutes with the help of all the departments–locations, transportation, makeup, hair and costumes. "Camera never waited," Junco says.

For an action scene in which Tony Stark was kidnapped, Heffron, Moore and Junco had to assemble a team of 50 "insurgent" extras in L.A.–a polyglot of Egyptians, Iranians, Tajiks, and Afghanis (including one Mujahideen). "We didn't want to be too specific ethnically," Heffron says.

One of the most challenging things about the "insurgents," who were divided into stunt extras, action extras with weapons experience, and regular extras, was maintaining continuity. Their placement in and out of the cave had to be mapped out in advance so that "we wouldn't inadvertently kill a prominently featured extra in scene 1 and then later find him alive in scene 51," Junco notes. "Not to mention the cave was shot in two entirely different locations. The interior of the cave was shot on stage at Playa Vista in Los Angeles and the exterior was shot in Lone Pine, Calif."

The 50 background actors were transported five hours away from L.A. to Lone Pine, east of the Sierras, where they shot for two weeks. The 2nds coordinated the logistics and put the extras up in hotels. They also hired additional extras from Edwards Air Force Base. The soldiers added authenticity, but created different issues.

"The military demands precision in timetables, which is so different from our industry," Junco says."Anything we needed had to be requested and cleared months in advance and if anything changed with our schedule, they couldn't guarantee we could have what we needed. On one day we lost over half our background to an unexpected inspection."

The soldiers had never been on a movie set. "We had to teach them all of the relevant terminology and frequently remind them of their marks and movements," laughs Junco.

To prepare for their job, ADs must be keen observers of life. Years ago, 1st AD Geoff Hansen, who worked on National Treasure and the sequel, attended a bingo night in Chicago to get a feel for the event. He tries to avoid what one mentor called "Mayberry background," and incorporates "specialty" extras for pizzazz. For instance, he included a Boy Scout troop in one crowd scene in National Treasure. "They fit in. It's not just tourists with cameras," he says.

National Treasure 2nd AD Christina Fong studies her environment in real life whether she is at a sporting event, a bar, on the operating table, or rubbernecking at a freeway crash. "I take a second and think, 'Wow, that's what it needs to look like.'"

Hansen and Fong used 200 background actors for a gala scene at the National Archives, filmed on a soundstage on the Disney Lot, in which Ben Gates (Nicolas Cage) steals the Declaration of Independence while bigwigs sip champagne.

In the extras breakdown, Fong called for women, military, waiters, bartenders and musicians. "There were people dressed in upper-class military. How many of those? What ranks are they? You have to go into detail. What is the ethnicity and age?"

COSTUME DRAMA: 2nd AD Christina Fong (above, behind boy

COSTUME DRAMA: 2nd AD Christina Fong (above, behind boy

with sparkler) sets the background for a nighttime period

scene in National Treasure: Book of Secrets.

Fong and 1st AD Geoff Hansen go over the next task.

After getting approval from director Jon Turteltaub, she met with the background casting professional who provided pictures. She worked with the costume department to calculate how many fittings they needed. "There were massive amounts of fittings for the gala," Fong recalls. "We had fittings for all the maitre d's and all the military. On shooting day, your call time for the women, of course, is usually two to three hours before the crew time to make sure they're ready to go."

Fong worked with three ADs and six PAs to shepherd the extras through the hair, makeup and costume departments. And during rehearsal, Fong likes to look through the camera to frame the shot."I place the background accordingly," she says. "I know Nick Cage is going to walk in. He's going to cross in here. He's going to walk over to Abigail (Diane Kruger). I need to make sure that I don't block them, that no background runs into them and that it looks as natural as possible."

Fong wanted the extras, drinks in hand, to look like they were having fun. She set the background close to the cast. Second second AD Katie Carroll set the action farther away. Then Hansen put on the finishing touches. "I'll drive her crazy tweaking it," cracks Hansen. "But Christina really gets the movement of people cutting against each other to keep the scene active and flowing."

The end result was so realistic that when Hansen and his family later toured the National Archives on vacation, the guides felt compelled to point out that the scene from the film was not shot on location.

It came off with a "smash," Fong says, but when she set background for a Mount Vernon birthday party for the president (Bruce Greenwood) in National Treasure: Book of Secrets, she had to brave a downpour. They rushed the 250 extras in gowns and tuxedos indoors. When filming resumed, the ground was soaked and the women's shoes were covered with mud. "We used lots of umbrellas, raincoats and prayers to complete the scene, although everyone was cold, wet and tired," Fong says. "You look at the scene now and the background looks gorgeous. The food and drinks look pristine. Of course, it was trashed."

If nothing else, 2nd ADs must be organized. "We all have really clean houses," jokes Fong. But they relish the challenge and creativity of setting background. Many put in extra hours to finish the call sheet so they can spend more time on the set.

Castaldi's baptism as a 2nd AD was on The Alamo in 2004, which called for 10,000 background actors. He selected the Texans and Mexicans, outfitted them, and taught them how to use powdered weapons. Castaldi, who estimated he knew 5,000 of the extras by name, always tells the backgrounders what to expect. "I rarely sugar coat it," he says. "There are a lot of people who say, 'Bring in the damn extras.' I was never that way. They play an important role and I treat them as such."

He estimates that he has answered at least 100,000 questions, but sometimes he's had to be tough. On The Alamo, one extra threw a soda can in a cannon. Castaldi pulled the can out and reiterated the dangers. "We took his gun and bandoleer away and said he couldn't be on the set. Everyone understood the point immediately."

In the end, if the 1st and 2nd ADs do their job well setting background, their work will go almost unnoticed and become part of the bigger picture. Audiences don't usually go home and say, "Did you see that background?" But their contribution is immeasurable to the success of a film.

"Scorsese and other directors want people who will not just keep them organized but who also can contribute creatively with the background action" Reidy says. We are part of the filmmaking process. We're there to help the artist. We're looking for people who have some taste and creativity, so that they can help in creating the world of these movies."