BY SHAWN LEVY

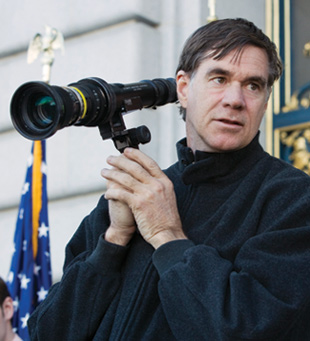

MILKMAN: Gus Van Sant, filming in front of City Hall in San

MILKMAN: Gus Van Sant, filming in front of City Hall in San

Francisco, realizes a lot is at stake with Milk. "They're going

to kill us if we get it wrong." (Photo Credit: Focus Features)Here's something you wouldn't guess: Gus Van Sant is a golfer.

"I don't play much," he says. "I play just infrequently enough so that I don't develop bad habits."

Not developing bad habits: That's as good a description as any of Van Sant's career, a singular series of transformations and switchbacks that has included early acclaim as an icon of indie and gay cinema for such films as Mala Noche and Drugstore Cowboy; commercial success and Oscar and DGA nominations for films like To Die For and Good Will Hunting; and a return to doggedly independent moviemaking with four low-budget films including Elephant and Paranoid Park.

Van Sant has changed his shape and focus so determinedly over the years that he has, by and large, avoided lapses into the predictable or familiar that can pester even a thoroughgoing artist. In individual films, and, indeed, in his career trajectory, he has found a balance between harsh reality and poetic lyricism. There are similarities among his films, but after a dozen movies it seems possible that his next might be of almost any size, stripe or style.

That could be because he has a refreshing attitude toward work more typical of a young artist with far less experience. "You can pick your direction, you can get the job," he says. "But do you want the job? So far, I haven't considered any of the films I've made exactly jobs. When it's not a passion, that's when you know it's a job."

As it happens, the film to which his passion has now led him is Milk, a biographical portrait of Harvey Milk, the openly gay San Francisco city supervisor who was murdered in 1978, along with Mayor George Moscone, by another city supervisor, Dan White. Van Sant's film is the winner of a long-running derby to bring Milk's story to the screen, a race so protracted that Van Sant himself had been attached to a version of it more than 15 years ago with Robin Williams touted for the lead.

The Milk that he has finally made, due on the festival circuit in September, stars Sean Penn in the title role and Josh Brolin as his killer. It's a full-on period film–the first of Van Sant's career–and at $20 million it cost more to make than the director's last four films combined.

Those four dreamy, spare, elusive films–Gerry, Elephant, Last Days and Paranoid Park–saw Van Sant reversing his career, in effect, diving back past his commercial pictures to the adventuresome, makeshift, nearly documentary films with which he started his career. But the new quartet stands as well as an extended, heartfelt meditation on the tragic nexus of youth and death, a theme Van Sant has explored throughout his career. And making it allowed Van Sant to return to working quickly, cheaply and with uncontested authenticity.

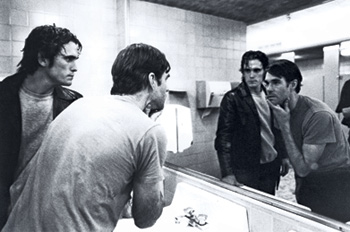

NITTY GRITTY: Van Sant (right), directing Matt Dillon in Drugstore Cowboy,

NITTY GRITTY: Van Sant (right), directing Matt Dillon in Drugstore Cowboy,

shoots for authenticity with a do-it-yourself approach. (Photo Credit: AMPAS)In his early films like Drugstore Cowboy and My Own Private Idaho, some of that authenticity was the result of extremely low budgets, which required Van Sant to take a do-it-yourself approach to wardrobe, décor, locations, and schedules. But some of it came out of his long-held belief that art, like golf, is sometimes done best when it's done in the freshest and least self-conscious way.

"It was easier then because we were such a small crew that we were able to go into a place, or be outside of it, and we could just shoot and the real people were there, and the background was real. The machine is less huge and less divided up. But when you get bigger and more organized, it's no longer all in the director's control, and you have to be really clever."

While making Idaho, for instance, Van Sant applied some cleverness to evoke the world of street hustlers after he realized that his casting people hadn't delivered the sort of extras the film called for. As he recalls, "The background that our extras person brought in... tended to be more like suburban kids, and they didn't have any of the true type of desperation that you'd see in the characters." So he shot small scenes in which he interviewed the actual street kids who inspired his fictional characters and mixed them into the film. "We would do little improvs with our real characters to make it seem like there was more of an authentic atmosphere [and] fake over the fact that we had really bad background."

Then after a period of making studio movies in the late '90s–Psycho, Finding Forrester–he cleansed his palate with Gerry, in which Matt Damon and Casey Affleck wandered at first comically and then fatally through a desert. Following that, he stripped away the apparatus of filmmaking even further for Elephant, a tragically lyrical vision of the Columbine High School shooting, which was cast almost entirely with kids discovered at open calls in an effort to get as close as possible to the reality that had inspired it.

"Everything was authentic," says Van Sant. "The lead characters wore their own clothes, so everything was taken care of. It wasn't period; you didn't have to fake it. All the kids were really high school kids, so nothing could ever go wrong."

The success of Elephant–including a Palme d'Or and best director trophy at Cannes–led him to a similarly open-minded casting strategy for Last Days, a speculative version of the final days of suicidal rock star Kurt Cobain. While preparing that film, Van Sant and his wardrobe crew were visited by a pushy Yellow Pages ad salesman who was peddling his product; Van Sant promptly cast the fellow in a scene. In his most recent film, Paranoid Park, in which a teenager struggles with his conscience after causing a fatal accident, an almost entirely non-pro cast included an actual Portland policeman playing an important role as a cop. If these choices can seem random, the results feel carefully crafted.

HIGH AND LOW: (top to bottom) Van Sant moves comfortably from

HIGH AND LOW: (top to bottom) Van Sant moves comfortably from

studio pictures like Good Will Hunting with Minnie Driver and Matt

Damon to low-budget indies with mostly non-pros like Elephant and

Paranoid Park. (Credits: Ed Kraychyk/Miramax; Everett; Photofest)A lot of directors would be justifiably wary of relying so heavily on amateurs to play big roles. Van Sant acknowledges that there's a delicate balance between discovering the right newcomers and coaxing performances out of them. "A lot of times," he says,"non-professionals don't know it's hard. And you say, 'That's remarkable; you do that as well as a real actor.' And you can really screw them up, because when they start to think about it, they overthink it, and they don't do it the same way anymore."

It helps that Van Sant tends to be quiet on the set. "You can make people uptight if you're uptight," he says. "So, I'm often pretending to be relaxed because it's so chaotic." But there's such a thing as being too taciturn, he admits. When he won his Oscar for Good Will Hunting, Robin Williams thanked Van Sant "for being so subtle you were almost subliminal." The director agrees that Williams' joke gets at something true.

"I'm the kind of director who doesn't communicate really well with actors," he confesses, "which is not something I'm particularly proud of. There are film directors who might be visualists, but they're not like theater directors who are used to breaking it down and then building it up with the actors on a stage. I can talk about the character. That's not what I'm unable to do. It's the actual manifestation of the scene and breaking down the motivations of the characters within a particular scene. There start to be too many possibilities."

Instead, he prefers to tailor the characters to the cast, allowing the real-life personalities and habits of his actors to bleed into their roles. "I focus on things that are actually happening in reality," he explains. "If they're playing with their car keys, I'll say, 'There! That's it!' And they'll say, 'What? That's not in the script.' But I'll make the scene about that because, to me, that's what's really happening in the moment."

Van Sant's willingness to let the energy and reality of a moment give shape to his films is evident in other aspects of his work. He shot Milk with cinematographer Harris Savides, with whom he's made five of his last six films. They don't storyboard, but rather they discuss the film in terms of styles and technical approaches, leaving room to alter their strategies as they discover what they're filming.

"We had theories of what we were doing with the cinematography on Milk that were different from the small films," the director says. Some of the caught-on-the-fly feel of his recent work informs Milk, but the airy, spacey tracking shots of, say, Elephant or Last Days, are gone.

Indeed, he didn't realize going into those films that they'd be so filled with long, empty shots. "Sometimes on those films we had references from other films–documentaries by Frederick Wiseman, for instance–but we ended up with something more composed, like The Godfather. We had that in our heads. But each film has been a journey in figuring out what we were going to do."

That license to reinvent the visual style as the film goes along is grounded in a rigorous discipline in the production schedule; a lot of editing and reshaping is taking place even as it's being shot. Van Sant developed a routine during his recent smaller films. "Saturday I'd edit, and Sunday we'd watch it," he explains. "We shot in sequence, so I would edit it as we shot. They were only 17-day shoots, so each edit was like one-third of the movie–about 30 minutes. So after shooting for five days, you were watching the first third of the movie. And then the second week I'd add the next half-hour. And after the third week you saw the whole movie. We kept editing after that, and things would change, but they were pretty close to the finished film."

It's fitting that Van Sant should be so concerned with verisimilitude because so many of his films are based on reality or a thinly disguised version of it. In Milk, however, the stakes are higher. So many people wanted to film the story because Harvey Milk, the first avowed homosexual elected to any notable public office anywhere, is such an iconic figure. Van Sant understands that the need to be faithful to the facts of this story trumps his notion of merely achieving a truthful atmosphere.

"You're talking about Dan White and Harvey Milk and George Moscone," he says, "and you can't twist it into your own idea. The city is very proud of that story, and they're very happy to have it become a film. Everyone in San Francisco has been very helpful. But they're going to kill us if we get it wrong."

To get the facts right, as well as the atmosphere, Van Sant had to rebuild the Castro district of San Francisco as it looked three decades ago, when it was even grungier and splashier than it is today. The cars, clothes and signage on the street needed to be built rather than, as in his recent films, discovered out there in the real world. Van Sant knew the San Francisco of the '70s slightly, but not the parts of the city that appear in the film, so he had to rely on his department heads for the sorts of tasks he could oversee personally in smaller films.

"Milk is a period film," he says, "and that means everything has to be redone or else it's not part of the period. Your background has to be consistent with the time, but they're modern people with old-time hats and haircuts and clothes. So it's easy to get inexact or incorrect. That's the part that gets me the most crazy. It's common to just show up–I'm sure every director's had this happen–and all your extras are just wrong."

Ultimately, the desire to get it right may be the most striking thing about Van Sant's roaming body of work. He has a collegiate curiosity that impels him, an art-school willingness to pick up an object and do something with it, a deeply felt, low-fi, why-not-let's-try-this aesthetic. There's also a Huck Finn quality to his films: his heroes light out for territory, or at least dream of doing it, or die trying. Hipsters, freaks, schemers and broken angels are thrown out into nature and the open road.

In that context, his commitment to live and work in Portland, where he's made five films and parts of a couple of others, makes perfect sense. In Van Sant's opinion, living in the city where he attended high school and learned his craft is a way to keep his head and art clear of a sort of alien residue that it might take on if he worked somewhere else.

"I've lived in L.A.," he says. "And I got the L.A. experience. And I started to get the same references that everyone else has, and my viewpoint started to become the same viewpoint from which everyone else was working, which is an L.A. viewpoint. And it starts to influence your art. Certain filmmakers it doesn't make a difference to. David Lynch is just fine. He can be his own person. But I start to absorb the atmosphere. So to not be geographically in the same place [as everyone else] is helpful."