BY GARY GIDDINS

(Credit: Photofest)

(Credit: Photofest)American political movies constitute a genre as predictable and shopworn as Westerns, mysteries, or screwball comedies. They vary in reflecting national moods—fear, sentiment, anger—but almost always assume that politicians are, by nature, crass and dishonest, except for the lone idealist who tends to lose either the fight or his ideals. Filmgoers know that Barack Obama is hardly the first to run on a plank of change and diplomatic boldness. His predecessors include Senator Bill McKay, whose election was engendered by the pledge "There's got to be a better way," and President Jordan Lyman, who argued that we had "the strength to win without war the struggles for liberty throughout the world." And then there's District Attorney Jim Garrison who observed of the assassination of President John Kennedy, "I can't believe they killed him because he wanted to change things."

True, these and other like-minded visionaries are Hollywood fictions—not least, Garrison in Oliver Stone's JFK (1991)—yet they illuminate the nature of real-life political desire: the dreams of millions that a better America may be incarnated in the platform and charisma of one candidate who cuts across the grain of conventional wisdom. Indeed, a journey through more than two dozen political feature films made since 1939 suggests that idealism and disillusionment may seem awfully déjà vu to film lovers.

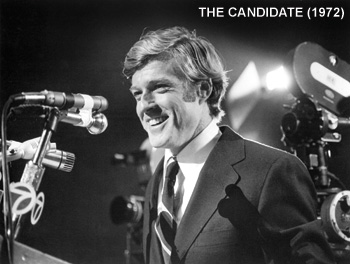

Bill McKay, as played by Robert Redford in Michael Ritchie's The Candidate, shares Obama's allure of youth and resume of community activism. Made in 1972, the year of the Watergate break-in and the McGovern debacle, it conveys the hip cynicism of the period. Voters are asked to choose between the wily old Senator Crocker Jarmon (Don Porter), who is owned by the usual special interests, and McKay, a handsome idealist, who auctions off his ideals as the possibility of winning becomes a reality. Neither of them says anything substantive, preferring to mine their particular banks of platitudes about experience versus change. The film has two fearsome moments that capture the mood of the times but also echo earlier movies.

In the first, McKay speaks jabberwocky to a union gathering (for which he arrived late, having been waylaid by a groupie), and responds to its cheers with the kind of self-satisfied smirk Broderick Crawford posed in Robert Rossen's still-potent 1949 film of Robert Penn Warren's All the King's Men. Like McKay, Crawford's Willie Stark, a thuggish caricature of Huey Long, also began his campaign with ideals, but found raw power to be more enabling. McKay's curtain line—What do we do now?—is an expression of idealism turned into ennui. Stark's curtain is brought down by an assassin, but not before he built a few good roads. One wonders if McKay will accomplish even that much.

The other resonant moment occurs near the end of The Candidate, as the triumphant McKay finally wins approval from his powerful father (Melvyn Douglas), who, cackling like Mephistopheles signing up another soul, baptizes him: "You're a politician!" Compare that to Frank Capra's 1948 film of the Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse play State of the Union, in which Grant Matthews (Spencer Tracy), an exemplary businessman turned presidential candidate, is similarly embraced by the devil's brood.

Matthews is truly a fantasy figure: a Republican who supports the Marshall Plan, world government, and universal healthcare. "The wealthiest nation in the world is a failure," he says, "unless it's also the healthiest nation in the world." However, his mistress (Angela Lansbury, as wickedly icy as she would be 15 years later in The Manchurian Candidate) convinces him to "play ball with anybody to get that nomination." In the climactic scene, a roomful of actors who specialized in rascality—Adolphe Menjou, Charles Dingle, Raymond Walburn—salute him for becoming one of them. This being Capra, and also a Spencer Tracy-Katharine Hepburn movie ("I'd rather be tight than president," she crows in a memorable drunk scene), he does a last-minute hokey-pokey back to idealism and the sanctity of marriage.

The range of presidential competence and aspirations is evident in a memorable trifecta from 1964, all three reflecting the terror of the times roused by the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. The aforementioned President Lyman, as portrayed by Fredric March in John Frankenheimer's Seven Days in May (1964), is at the end of his term. He has the same approval rating enjoyed by our current president, 29 percent, but is a dyed-in-the-wool liberal. Determined to negotiate with the enemy, he is accused of appeasement by a high-ranking general (Burt Lancaster), who is secretly preparing a coup d'état. Informed of his impending ouster (by Kirk Douglas), Lyman is not ready to junk the Constitution in a world succumbing to hysteria, and he is too righteous to blackmail the general for adultery. Fortunately, screenwriter Rod Serling provides him with a convenient deus ex machina.

(Credit: Photofest)

(Credit: Photofest)Seven Days in May was made in the same year that produced two doomsday scenarios: Stanley Kubrick's inspired burlesque Dr. Strangelove and Sidney Lumet's unintentionally batty Fail-Safe, both with the same plot (which occasioned a plagiarism suit). Strangelove's milquetoast Merkin Muffley (Peter Sellers) tells the Soviet premier, about to be accidentally nuked, "I am as sorry as you are, Dmitri. Don't say that you are more sorry than I am because I'm capable of being just as sorry as you are. So we're both sorry, all right?" And then, ineffectual in his own way, the president in Fail-Safe (Henry Fonda) disappears into a bunker, hoping to negotiate his way out of the same nuclear accident. One member of his staff champions a total attack, confident that our sheer might will shock and awe Russia into surrender. Nixing that idea, the president invites the Soviets to nuke New York, where his wife is shopping.

In every decade, this dismal view of the political present is invariably contrasted with a political past that is presumed to be as pure as Eden and as magisterial as Greece. Indeed, three clichés are so prevalent in these films that a young director venturing into the genre might put them at the top of a must-to-avoid list: 1) musical scores that involve snare drums (The Candidate, Seven Days in May, JFK, Primary Colors, Advise and Consent); 2) scenes at the Lincoln, Jefferson, and other memorials, especially where the protagonist stands next to a black or Euro-ethnic citizen as the voice of God intones the Gettysburg Address (Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Yankee Doodle Dandy, State of the Union, JFK, Born Yesterday, The Day the Earth Stood Still, Advise and Consent, Nixon); 3) concluding civics lessons (nearly every Washington-based film ever made other than Strangelove, blessed be its name).

Two classics from 1939, Capra's Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and John Ford's Young Mr. Lincoln, suggest the genre's playing field at a time when the nation was held in the balance between Depression and war. Capra pits a patriotic rube (James Stewart) against a government in thrall to lobbyists and crooks. Smith delivers a civics lesson in the form of a filibuster, but despite his decency, the cheers of children, the bemusement of the vice president, helpful hints from two press pals, and the villain's improbable turnabout, Mr. Smith still ends up depleted and unconscious on the senate floor.

In State of the Union, a decade later, Capra's cynicism is more corrosive, his plea to our better natures more fantastic. Karl Rove might have learned his stuff from its invocation to keep the public divided. "Play on hatreds," a tactician insists, "Keep them voting in blocks!" But Hillary Clinton would not have found much succor in the dying poll who lauds his daughter for combining "a woman's body with a man's brains," or from Hepburn's character, usually the smartest person in the room, who says, "No woman would ever run for president—she'd have to admit she was over 35."

Ford's films are elegiac and yet they take change in stride: The past is always dying and the present is always being born. So in Young Mr. Lincoln, Abe's political enemies may be shortsighted, bigoted, and dumb, but they aren't evil, as they often are in Capra films. Ford's nostalgia for the old way is invariably balanced by his grudging acceptance of the new.

(Credit: Columbia Pictures)

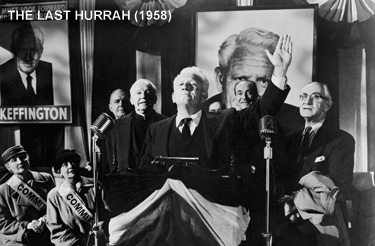

(Credit: Columbia Pictures)Almost 20 years later, Ford was still hoping for the best in people and politicians to surface. His version of Edwin O'Connor's largely forgotten novel The Last Hurrah (1958) concerns the final mayoral race of a political boss, Frank Skeffington (Spencer Tracy), who uses blackmail and humiliation to guarantee support for a good and necessary bill. His methods are deplorable, yet he is a beacon of realpolitik, defending the interests of the shanty Irish against old-line plutocrats who put their support behind a compliant idiot. On the other hand, the moral center of the film is a simpleton named Ditto (Edward Brophy's last and finest hurrah as an actor), a man of unwavering loyalty. Skeffington steals a line from Tocqueville in describing politics as America's favorite spectator sport—and Ditto is its most ardent fan. In the end, he alone climbs the stairs to Skeffington's deathbed, occupying the closing shot.

Still, when the cardinal in The Last Hurrah asks, "Where are the best people?" a monsignor tells him, "Not in politics." That may apply as well to political films. In the 1940s and 1950s, political corruption was often depicted as a local phenomenon, as greedy megalomaniacs conspired to loot and control their towns. The battle between the political boss and the compromised reformer is indelibly realized in Citizen Kane, and reappears in countless less-gloried films, culminating in Otto Preminger's goldfish bowl of scheming congressmen, Advise & Consent (1962). This film revels in bickering and maneuvering, most appallingly in a ruse by which a pint-sized scoundrel, Senator Van Ackerman (George Grizzard) blackmails another senator over his homosexual past and precipitates his suicide. Yet in the inevitable civics lesson, the grizzled senators, played by Walter Pidgeon and Charles Laughton, congratulate each other for being patriots. The government, except for a rotten Napoleonic apple or two, is in good hands.

That kind of blind optimism became more difficult to float after Watergate, and the cynicism of films like All the President's Men, The Parallax View, The Dead Zone, Wag the Dog, Nixon (Richard Nixon as Richard III), Primary Colors (the Clintons as Faulkner's avaricious Snopes family) and Election (the high school version of blood-sport politicking) reflects a presumptive fear of politics. The government is no longer ours—it is, rather, a secret operation, running private wars and upending elections, spying on citizens, and frisking them at airports. George Orwell wrote a book about it. Obama or John McCain would have to be more than politicians to undo all that mischief; they would need the confidence and sanguinity of Henry Fonda, Robert Redford, Spencer Tracy, and Morgan Freeman, and they will need directors and scriptwriters as well as speech writers.