BY JEFFREY RESSNER

Photographed by Michael Kelley

Having directed only a half-dozen feature films over the past quarter century, James Cameron has certainly proven that quality can trump quantity. Despite his relatively low output, few directors have contributed as much to modern filmmaking technique as the one-time truck driver who went on to create Titanic; the original Terminator and T2; the supercharged sequel Aliens; the spy comedy True Lies; the underwater fantasy The Abyss; and, coming up in 2009, the highly anticipated 3-D epic, Avatar.

Having directed only a half-dozen feature films over the past quarter century, James Cameron has certainly proven that quality can trump quantity. Despite his relatively low output, few directors have contributed as much to modern filmmaking technique as the one-time truck driver who went on to create Titanic; the original Terminator and T2; the supercharged sequel Aliens; the spy comedy True Lies; the underwater fantasy The Abyss; and, coming up in 2009, the highly anticipated 3-D epic, Avatar.

What's more, he's a great interview. Intellectual without being intimidating, Cameron is a visionary who enjoys articulating his often complementary desires to stretch the imaginative boundaries of the medium and change the way we watch movies. Raised in Canada where he devoured outer space and fantasy tales, his family later moved to Southern California, bringing him closer to his calling. After getting his start in movies by building spaceship models for Roger Corman's New World Pictures, he soon went on to handle second-unit chores, took a job directing Piranha II: The Spawning, then broke big by writing a script about a time-traveling cyborg called The Terminator, which he insisted on directing as well.

For the past three years, Cameron has been absorbed with a new digital form of 3-D filmmaking, which he prefers to call "stereo," for the otherworldly Avatar. Sitting at a large wooden table in the cavernous dining room of the Malibu house he uses as his postproduction base, the 1998 DGA Award-winner sipped a cup of coffee and spoke nonstop for two hours about his lifetime quest for new cinematic thrills.

JEFFREY RESSNER: Not long ago, Steven Spielberg was discussing special effects at a press conference for the new Indiana Jones movie and said, "I believe in practical magic, not digital magic." Care to respond?

JAMES CAMERON:

Steven is the master. He's the sensei we all learn from and he's continuously reinventing himself so we can continuously learn from him. But I disagree with him in some areas. He still edits on a KEM, which seems kind of donkey stubborn but which is obviously his comfort zone, how he connects with [his material]. For me, however the technology of moviemaking evolves, I want to be at the cutting edge. I want to be riding the wave. I don't want the wave to wash over me and be looking at it from the backside heading toward the shore with everybody else riding it. I happen to enjoy that part of it a great deal. On the other hand, the great balancing act of technical filmmaking is to never let the technology intrude stylistically to the point that it interferes with narrative storytelling and the heart and soul of the movie. I would say I definitely didn't get it right on The Abyss. But I did get it right on Titanic.

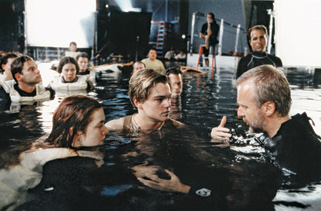

SINKING FEELING: Making the $200 million Titanic was physically taxing,

SINKING FEELING: Making the $200 million Titanic was physically taxing,

but Cameron, working here with Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet

in the tank in Mexico, managed to keep his head above water.

(Photo Credit: Kobal Collection)

Q: The film that led the way for you was 2001: A Space Odyssey. But do you recall the very first movie you ever saw?

A:

No, I really can't, probably some Disney film. But the first film that made a significant enough impression upon me where the afterglow didn't fade for weeks was Jason and the Argonauts. I remember distinctly my grandfather taking me to the local cinema in Ontario, and being absolutely blown away by the film's vivid colors, the brightness, the reality of the skeleton fight. Of course, looking at it four decades later, it's laughable. But I came back to my third-grade class and began quickly sketching my own version of the movie. I was a pure, avid consumer of fantasy in movies, in books or wherever. Later on during high school, my bus trip lasted an hour each way, and so I typically read a novel every day on that ride, usually short science fiction novels.

Q: When did you realize that you could be a director?

A:

Well, I had worked on production design for these Corman films, and I had high standards even though we were working on low budgets. I'd watch some directors just consistently screw up scene after scene. They wouldn't know where to place the camera or how to light it. I thought: if that's a director, I could do that. There was no question in my mind that I could do it, but that leap wasn't made until I saw other people doing it poorly. Now, there's a certain hubris in that. Then, of course, you're confronted with that first day when you are actually "The Guy" and you're calling the shots, you're placing the camera and so on, and it can get pretty daunting. When you don't have any experience, ultimately that stuff has to become reflex, and you need to build muscle. By the time I did Terminator I had plenty of confidence and enough experience, fortunately, not to mess it up too badly, given it was pretty low budget and shot pretty fast.

Q: The Cameron style in The Terminator continues through Aliens and your other films—this velocity level, in which the audience feels as if it's being whisked along on a wild ride. How did you develop that style?

A:

There wasn't a "Cameron style." I'm not even sure there's one now. I'm always trying to strike out on new paths. Like a skier that only likes virgin snow, I go for the fresh powder. With Terminator I didn't have a style, I had a lot of ideas. I wasn't influenced in a film school, film aesthetics way going back to John Ford or Lubitsch, but more by what had recently been at the movie theater. It's kind of the anti-Scorsese approach. Martin totally goes to school on the aesthetics of the European filmmakers. I don't. I just like movies, and I sort of throw it all into a blender and what comes out is what makes sense to me in the moment, with no attempt to impose a specific style on it. I remember on True Lies consciously disciplining myself to go with a longer focal length, to pull the camera back and create more compression in the frame, just because that's what everybody else was doing. But it was not distinctive for me and I abandoned it when I got to Titanic and I've never done it again because that's not how I see things.

Q: So if you don't look at your work in terms of style, how do you think of it?

A:

I think of it as storytelling. It's like, what does this scene demand? What am I trying to tell the audience? What's one character doing to the other character? What's the character thinking but not saying? Is the moment threatening? Is the moment epithermal? I push myself to try to go to places outside my comfort zone. I look at other films and the things that impress me are not the big action sequences. They're not the big, hyperkinetic pyrotechnics and CG stuff. Big effects sequences are relatively easy. They're expensive as hell. They're grueling to make. But they're relatively easy because they are what they are, generally speaking. The things that impress me are when a filmmaker can very quickly and efficiently evoke some kind of out-of-body, transcendental state where I'm 100 percent connected to the characters. I know what they're thinking and what they're feeling even though they may not even be saying anything. That, frankly, still induces awe when I see that because I think that's one of the hardest things to do.

Q: The Terminator has several moving scenes between Sarah Connor [Linda Hamilton] and the soldier from the future assigned to protect her [Michael Biehn]. As someone who had specialized in small models and special effects, how did you deal with flesh-and-blood talent?

A:

I had done a little theater in high school, but I really had no training whatsoever dealing with actors. Zero. I think my doorway into them was the writing. I created the characters, and the actors were fully committed to playing these characters, so we had a lot to talk about. It was that simple. When you've got a lot to talk about with somebody, you find some bond and form a working relationship. I've always found it very easy to get along with actors, and they find me easy to work with because, probably, I talk too much. I've had to tell myself over the years to back off and give them things so they can act in the moment as opposed to the big picture stuff, because sometimes actors can't hold all that in their minds and they're just looking for a little truthful moment.

These days, I find the HD is really nice because you don't cut and, unless it's a Steadicam shot, which I don't do, I'll operate everything else—the crane, the dolly, the handheld. So, usually I'm right there and I'll just quickly reset and I'll say, "Hey, give me that again, fast. Push this or push that or feel this." Some actors really respond to that because they can stay in the moment. It's not "Cut!" and then the pit crew comes in and it all collapses and then people are joking around and the spell is broken. With the HD, they can stay in the spell. It's a little bit like you've got this coach whispering in your ear, "You're there, you're still in the game. You don't have to stop. Nobody's blowing the whistle."

Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio and Ed Harris confront the

Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio and Ed Harris confront the

water creature in The Abyss (1989).

Cameron had plenty of confidence but no experience working

Cameron had plenty of confidence but no experience working

with actors when he made The Terminator (1984)

with Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Making Aliens (1986) was a steep learning curve for Cameron

Making Aliens (1986) was a steep learning curve for Cameron

as it was the first time he worked with an ensemble cast.

Cameron is recapturing the spirit of being a young director

Cameron is recapturing the spirit of being a young director

on the 3-D live-action feature, Avatar.

The director teamed up with NASA to explore the Mid-

The director teamed up with NASA to explore the Mid-

Ocean Ridge in the 3-D documentary Aliens of the Deep.

(Credits: Photofest; MGM; AMPAS; 20th Century Fox; Disney)

Q: Your next film, Aliens, was really the first time you worked with an ensemble cast. How was that different than working with just one or two actors?

A:

Every scene in Aliens was a group scene so I had to get my act together and really start thinking through how to cover a group. How do you give each of them their correct amount of time? How do you not have actors feel slighted that they're getting left out of the creative process in a group? Not everybody in an eight-character scene can have equal time. So, yeah, it was a pretty steep learning curve on that film although all of that was secondary compared to just the pure technical, logistical problems. We made the film in England where the pace was about half the speed that we were used to. It was literally like just going from running to running through gelatin. Honestly, for a week we felt that we seriously were not going to be able to get the film done. We changed DPs; we had a lot of problems.

Q: The Terminator had some scenes with the robot, but with Aliens you had a whole character that was not human. Was that a different kind of challenge for you?

A:

That's the kind of fantasy filmmaking I wanted to be doing. I went to the guys I knew and had a good working relationship with—Stan Winston and his crew. We were out to beat Carlo Rambaldi and those guys that did the first Alien film, but we certainly set ourselves some harder bars to leap over by having the thing out in the open involved in a fight, an actual action sequence. The first film was really all about style and mood and a different kind of horror. My film was very different. It was about somebody going beyond their paralysis, beyond their overwhelming fear, to become someone who takes action. And the second it kicks into action, that's my turf. That's my forte. And so we set ourselves a whole set of different challenges, but to me that was the fun. I love that. It's the magic of moviemaking.

Q: What was it like directing both computer-generated actors and real actors in the same scene, such as The Abyss sequence where the leads confront that water creature?

A:

The question should probably be rephrased because they really aren't computer actors—they're actors. The pseudopod [in The Abyss] was Ed Harris and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio. The T-1000 [morphing cyborg in Terminator 2] was Robert Patrick. It was the issue of, instead of a director of photography and a shooting crew putting light onto an actor, you've got a bunch of CG animators and code writers, a completely different culture, who are taking what that actor does and capturing it in a very different way. So the actor and the director are the common elements between two completely diverse cultures that have almost no cross talk. As much as I tried to promote it when I was the CEO of [the special effects house] Digital Domain, I kept telling these computer artists, "You have to go to the set. You have to talk to a DP. You have to work on a live shoot and understand what it is to turn a light." Because they don't work that way. They work with a completely different tool set. And I think it's still a problem today. The big problem in CG is that the lighting tools are completely unintuitive for filmmakers. It's a big source of frustration every single day on Avatar.

Q: How would Aliens be different if you were making it today?

A:

Probably on that exact film today we'd do so much of it with CG. I'm making Avatar now where I've got people running around in leotards that are supposed to be on another planet with motion capture dots all over their bodies. And we're able to conjure some pretty stunning and vivid imagery, very realistic and very evocative, but it takes place in a complete fantasy environment. It sometimes literally takes years to make these shots complete. Literally years for one shot.

Q: On Aliens you worked with a child actress and one of T2's main characters was the kid played by Eddie Furlong. How do you deal with youngsters on the set?

A:

Carrie and Eddie were similar in that they had zero acting experience. I mean, they could have choked. So there was a real vetting process. It was finding that kid who could grab your heart. And I think it's the thing that every filmmaker faces when they build a movie around a child. You have to think the way they think, but you don't treat them like a kid, because they'll sense that. You have to treat them like an equal, but keep in mind that they're a kid, and they see things very differently. You can't burden them with too much story. You have to keep it pretty simple and pretty immediate. Eddie had kind of an energy problem, and it would take him a long time to build up energy in a scene. So I'd come in say, "OK, let's do some jumping jacks." And we'd just literally do jumping jacks together for a couple of minutes to get the heartbeat up. And then his brain would kind of switch on and shwooo, he'd go.

Q: Like most of your films, T2 has several jaw-dropping effects: the shotgun blast that splits open the head of the T-1000, the cyborg morphing from a pool of liquid metal into human form. How do you keep the effects from overpowering the storyline?

A:

You pick your battles. You want to take people to a place they couldn't have imagined for themselves. But it has to be organic to what you've already set up. It's not so much about the "holy shit" moments, as about the details that surround those moments and what builds to them. Now if you really step back from it, the whole thing is completely absurd, or at the least highly implausible. But you build it like bricks and mortar. You build it, you build it, you build it and you create the detail. The actors do most of the heavy lifting because their ardent commitment to these ideas is what convinces the audience that what they're seeing is real. When Sigourney Weaver looks at the alien queen stepping out of the shuttle's landing gear at the end of Aliens, you believe it's there. Now it's just a big piece of rubber, but you believe it's a living creature because Sigourney makes you believe it. That's how it works—the caliber of the performances makes visual effects work, not the effects themselves.

Q: Nowadays, actors have to perform against a green or blue screen or act opposite a placeholder stick that will be filled in later. What do you say to actors who haven't played in these areas before?

A:

Any actor can pick up a page of dialogue, get with another actor, and bang out a pretty good scene. From a director's standpoint, there's nothing to it—all you've got to do is make sure they're in the frame, right? But when the other actor's not there, that's when you've got some work to do. You've got to use every trick and every bit of communication that you know to create something that, in their minds, is dramatically real. So you talk a lot about what they're seeing, and try to show them what it is. I mean, it's pretty simple stuff. But you have to know what an actor can create with nothing there. When an actor comes in on an audition, they stand there in a room and they're supposed to be on another planet or in another time or on the deck of the Titanic. They're not playing against another actor, they have no set or wardrobe, but if they can do it in that moment, they can do it later. Which is why I would never cast an actor without an audition for this type of work.

Q: What are your auditions like?

A:

I'm not going to hire an actor who I don't spend a minimum of an hour working with. Most actors, unfortunately, come in thinking "I'm going to have 15 minutes and I'm going to wow him." So they work on the scene their way, or with their acting coach, or with a friend or whatever. They really care. They'll work the scene. So the first 15 minutes is theirs, the second 15 minutes is exploration. Then, after that, I'll hone in to see if not only can they take a new idea and run with it, but can they close the deal? Can they take an idea and build on it? Because that's how it will work on the set. I don't expect lightning to strike on the first take. If it does, the camera crew isn't usually ready for it. [laughs]

Q: With all the technical expertise and computer-generated things in your films, I don't imagine there's a lot of improv.

A:

Oh, absolutely, it's very improvisational. Even though I'm a writer, I don't go into acting scenes with a storyboard. I may have some general ideas about blocking. The first thing I do is ask the crew to step back and I'll do a blocking rehearsal with the actors where we'll try to find what makes sense visually in the scene. But what I also try to do is have a period that's a little more free floating. And if people have ideas they can throw in little bits of dialogue that maybe help them. I tell the studios that the script I give them is the first draft. The second draft is going to be done with the actors. The third draft is going to be done in editing.

Q: Aside from the box office, what most industry people recall about Titanic is the bad buzz that preceded the film. What did that teach you about the power of the press?

A:

I learned a lot about the media; that they can be rapacious. They can be sharks in a feeding frenzy, regardless of the facts. I'd never been attacked before, maybe in individual reviews or that sort of thing, but never before a film's release. People who had no idea what we were doing just thought it was great sport to attack us. We were made to look like the biggest idiots in history for making a movie where everybody knows what happens. OK, the big ship sinks. Big deal. What do you need to spend $200 million on that for? And, you know, you're way over budget. You've got to push your release date. I mean, we were tried in absentia and hung in effigy before people had seen a foot of the movie. In a funny way, it becomes a kind of test of character, I guess, because you can implode and crawl away and it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy on the media's part. But I'm not going to let them dictate that my movie's a dog. I'm going to make it the best movie I can.

SEA LEGS: Cameron (left), with his DP, was hands-on

SEA LEGS: Cameron (left), with his DP, was hands-on

making The Abyss, even under water. (Credit: AMPAS)

Q: How did you deal with that bad buzz on the set?

A:

It didn't affect our work. I think the actors are relatively immune to that stuff, unless they're a big movie star and the attack is against them. But Kate and Leo were respected and relatively young, you know, and they weren't the ones being attacked. We were also all so focused. Every film becomes its own little kind of solipsistic world, and you live within that world every day. Titanic got grim because it was hard work. It was physically taxing—the water and sinking the ship and all that. But Leonardo's a real joker on the set, and he keeps the spirits up. Every once in a while we'd play some practical jokes. We brought in a mariachi band on my 1st AD's birthday, right into the middle of a scene while it was being shot, just for fun. And everybody was in on it but him. Things like that tend to lighten the mood. You have to have a sense of humor. On Titanic I'd say I lost my sense of humor but on Avatar I haven't.

Q: Clearly we're in a transitional period in filmmaking craft right now. Avatar is sort of being looked at as the Great Digital Hope.

A:

I certainly don't want that put on me.

Q: Let's rephrase: what do you think Avatar has the potential to do for the 3-D cause?

A:

Here's what we're seeing in glimpses—it's a joyful experience on a moment-by-moment basis to live in that world. You sit down, you put on the glasses. Now, will it sustain for two-hours-plus? Nobody's made a 3-D movie this long before; we are setting out to carve out some epic turf. What we can say right now is that the movie has the capability to have a transportive effect on the audience. And I think that if, coming out of the theater, they associate the 3-D with that experience, then they'll think of 3-D in a different way: less gimmicky, more a natural tool of filmmaking, and a thing that makes them want to get out of their house and go to a movie theater. I think we need that.

Q: Obviously CGI has advanced a lot since you created the waterpod in The Abyss. How much have you been able to push the envelope on Avatar?

A:

We're doing effects up to a certain point, and then we throw it over the fence to the guys at Digital Domain to go to higher resolution. They've devised lighting software for Avatar that I think is going to revolutionize CG. It's what they call global illumination. And it's actually lighting the way things are really lit. If you're doing a day exterior, you have one sun. Normally you might have 40 or 50 lights to create the effect of sunlight by breaking it up into different areas. They just showed us 11 finished shots for the movie in the last couple of weeks and I showed it to friends who had no direct day-to-day contact with the production, and they said, "That's incredible. How are you doing that make-up?" They're not even asking the right questions. They're not even understanding that every single thing they're seeing is ones and zeros. It's all pixels. There's no tangible, physical reality to it whatsoever, but it looks real.

Cameron was honored to receive the DGA Award

Cameron was honored to receive the DGA Award

for Outstanding Achievement from his peers

for Titanic in 1997. (Credit: DGA Archives)

Q: You took part in a DGA symposium in March with Spielberg and Jeffrey Katzenberg about 3-D. Do you think there should be some kind of mentoring program in the directing community about working in 3-D?

A:

I'm not sure there's anybody qualified to mentor in 3-D. I think we're just figuring it out. It's like the first days of sound or the first days of color. It tends to predominate your thinking while you're making the movie and that's probably not healthy in the greater scheme of things. But I think anybody who's willing to work in stereo and get their hands dirty doing it should then give back something of what they've learned in that experience. To the extent that there are going to be some [format] rules, we need to kind of firm up those rules so we don't piss in the soup of the marketplace and give people bad stereo experiences.

Q: How can you share your experiences?

A:

Maybe we should start our Stereo Anonymous, kind of a self-help group, and all of the directors should get together in a circle and share their experiences. You know, stand up and say, "I'm a stereo addict," then go on about what they've learned. There's an amazing opportunity for directors to get together and talk about technique in the same way we did when we were young, to recapture a little bit of that spirit. That's how I feel on Avatar now. It's my seventh film, and I feel like it's my first movie almost every single day. I happen to love that. I don't ever want to get to a place of such comfort that I'm just a kind of cigar-chomping guy that leans back in a chair and entertains the people visiting the set while trying to keep an eye on what the DP's doing. That, to me, is not what directing is about. If I don't come home with my body aching, my fingernails black from having moved everything on the set personally, then I don't feel like I've been directing.

Q: How does a director take that leap of faith into 3-D?

A:

The first step to shooting 3-D using the new generation of cameras is you've got to make the conversion from film to HD. And a lot of established filmmakers just aren't willing to do that. Or they're kind of thinking about it. Well, you can't think about it. You've got to just grab your balls with both hands and jump off the cliff. It's that simple. And then, having made that transition, you now have to make a second transition, which is you now have to start thinking in 3-D. You have to start composing shots in 3-D, all that sort of thing.

Q: Do you think in 3-D as a director?

A:

I don't look in 3-D while I'm composing my shots. I compose it just on a flat monitor. And I don't edit in 3-D. So for me the discipline is imagining what the shot will look like in 3-D, but be satisfied with the shot aesthetically in 2-D. That way I'm always making a good 2-D movie as I go along. And that seems to work for me. Other people may do it differently. We have the capability on the set to view every shot in 3-D as we go along, but I'd have to walk 50 feet over to our little viewing space and watch it. And I've found it was taking a lot of time [because] everybody goes "Oh, wow, that's cool, play it again," and it was just too much fun. You can have a certain amount of fun on the set. But you can't have too much fun.

Q: You won the DGA Award for Titanic and many other accolades. What does the recognition of your peers mean to you?

A:

Well, it's nice to have the respect of people who understand how hard this stuff is. Because the blogosphere is full of imbeciles—none of whom have ever shot anything in their lives—nattering on endlessly about what idiots we filmmakers are. But, you know, I'll be at a little symposium with four or five other directors and, whether our aesthetics are the same or not, I know what those guys or those women went through to make their films—to get them financed, to go through all the battles with the studio, to maintain their creative integrity. It's a very, very small group and, unless you've done it, unless you've walked that walk, you don't know what it took.

Q: What do you think young directors need to do to be able to use this new technology?

A:

I think the biggest problem, the barrier to entry, is that it's still pretty darn expensive. So while it's possible to do a film that's completely CG and completely photo-real, it's probably cost-prohibitive. We're making a film that's 60 percent CG and 40 percent photographic and it's still borderline cost-prohibitive. Young up-and-coming filmmakers are not going to be making this type of movie right away, but you'll have directors dropping in scenes that elevate what is otherwise a more conventionally made film. And they'll learn the tools. I know that those directors coming up a decade or two behind me are not going to be burdened in a sense by all the old way of doing things. They're just going to get the tools in their head, it's going to be very intuitive and there's nothing that I can offer them in terms of advice. They're going to figure it out.

Q: I know you were inspired by 2001: A Space Odyssey. Did you ever meet Kubrick?

A:

I did—it was my 40th birthday present to myself. I was on vacation in Europe, and I called him up and said, "I'm coming over," and went to his house in England. My wife at the time was freaked out that I wasn't going to be back home for my birthday. But I said, "I'm going to meet Stanley Kubrick. There's no present, no surprise party, no nothing you could give me that would supersede that." So I went to see this reclusive guy knocking around this big house and he just totally wanted to know how True Lies was made. He had a print of it on his KEM down in his basement, and made me sit there and tell him how I had done all the effects shots. So I spent the whole time talking about my movie with Stanley Kubrick, which was not where I thought the day was going to go. But I want to be like Stanley, I want to be that guy. When I'm 80, I want to still be the guy trying to figure it all out.