BY STEVE POND

Illustration by Brian Stauffer

Blu-ray is the format of the future, unless HD-DVD is the format of the future. High-definition broadcast television in 1080i will revolutionize the industry, or maybe that's HDTV in 720p. Video-on-demand will change the way we watch... but then again, so will mobile TV, or Media Center PCs, or Telco TV, or...

Yes, it's confusing out there in the world of new technology. But make no mistake, there are changes afoot in home entertainment, in the way film and television will be delivered, shown, viewed and consumed. "The process of making films is getting dramatically more complicated as a result of all these different delivery platforms," says Gerry Kaufhold, a DGA consultant and the principal analyst for converging markets and technologies at the Arizona-based company In-Stat. Kaufhold, who presented an "Engineering 101" primer to the Guild's board of directors at a recent meeting, believes, "Every one of the new areas is going to deliver a different user experience, which is obviously very important from a director's point of view. And at the same time, every area might lead to new issues about payment method. So it adds complexity in two different dimensions."

Over the years, we've become accustomed to traditional pipelines through which film and television content flows: theatrical distribution, broadcast television, cable, satellite. But whereas those usual methods of distribution are all about taking a given piece of content and displaying it for a fixed audience, the new pipelines—be they broadband Internet, mobile, or the many other varieties—are adaptable to use content in many different ways, to repackage it, chop it up, make it interactive, rather than just showing a film or program the way we're used to seeing it.

Sony and DreamWorks, for instance, placed seven-minute clips from Spider-Man 3 and Shrek the Third on the Internet in advance of their release dates, drawing fans who comb the Net for fresh video content and who, crucially, have been found to watch for about seven minutes at a time. A business card dropped on the ground during an episode of Heroes—visible only to alert owners of digital video recorders who noticed, rewound and freeze-framed it—contained a working 800 number that divulged clues to the series' mysteries. Even celebrated technophobe Woody Allen made a podcast, available on Apple's iTunes, to promote his 2005 film Match Point. Jessica Simpson appeared as her Dukes of Hazzard character Daisy Duke in an ad for DirecTV, telling viewers that the service uses 1080i high-definition: "I don't even know what that means," she said, "but I want it."

But it's not just avenues for promotion that are changing. The implications of new technology will play out in how films, television, videos and commercials are made, and certainly in how contracts are negotiated. "When you're making a film now, you can't just be thinking about the big screen, or even the TV screen," says Kaufhold. "Because you have these wide-angle, high-definition screens, which look pretty nice, but you also have computer screens, and portable media player screens, and ultimately, mobile phone screens."

As technology leads the way, the business will follow, suggests Will Richmond, the president of Broadband Directions, a market intelligence and consulting firm specializing in broadband video and new technology. "As with most things technology-related, the technology itself is probably the easiest part of the game," he says. "The business models are still being worked out, especially when it comes to movies—but the impact is already being felt in short-form video and television, and it's coming to movies as well."

So filmmakers better have at least a passing familiarity with all of it—because for now, there's no telling how it will shake out, how the different formats will grow, what will flourish and what will fall by the wayside as companies decide what to push and what to toss. "At this point, nobody knows for sure what's going to catch on and what's not," says Kaufhold. "But we do know that all of these things directly affect the process of making a movie or a TV show, and also the process of distributing the content."

Which means that a brave new world is on its way—and if we don't have a crystal ball to make predictions about what will prevail, at least we can try to get a handle on what's in play and how it works.

The key factors that determine the availability of content in the digital age are: Storage (how a film or TV show is preserved in order to be transmitted to the viewer); Transport (how it gets to the viewer); Playback Devices (how the viewer watches it).

And outside of reels of film being projected on a big screen, we are talking about all three factors taking place in the digital domain. "It used to be that a film required reels of celluloid, and the only guy who could play that back was somebody with a movie theater and a projector," notes Kaufhold. "By going to a digital format, you enable things like DVD, which stores the film in a much smaller format, and you also gain the ability to deliver the movie over the Internet or to a cellphone. You improve the ability to store it, and the ability to move it around as well."

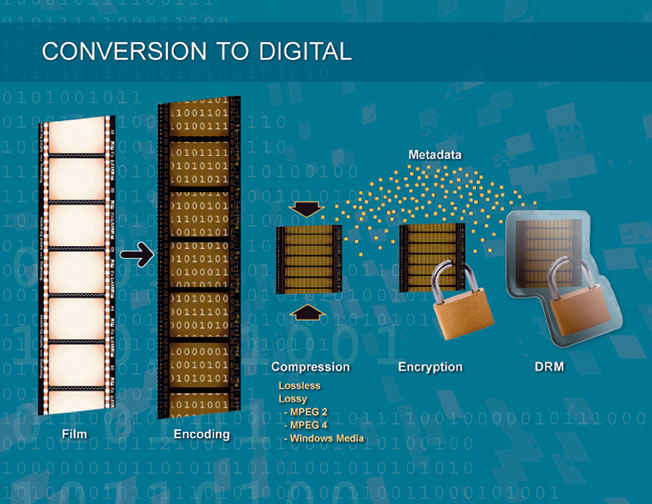

DIGITAL TRAIL: Many films and television are still not shot digitally. This is how

DIGITAL TRAIL: Many films and television are still not shot digitally. This is how

analog material gets converted and safeguarded. (Illustration by Tricia Noble)

GOING MOBILE: One of the big questions is how to get cool stull like Desperate

Housewives from TVs to cellphones. (Credit: Lon Atkinson/Verizon/ABC)

STORAGE: For films and television programs that aren't originally shot digitally—which is to say, half of the content created these days—the first step is the conversion from analog to digital. Encoding takes the analog material and converts it from images on film or video to a string of ones and zeroes. Simply encoding the material digitally, though, creates files too large and unwieldy to be used effectively.

The next step, then, is compression. Lossless compression is the ultimate for preserving original material, but again it results in files so large as to be almost unusable. "Lossy" compression reduces the size, but in a way that preserves the original to a degree deemed acceptable by the Motion Pictures Experts Group, an international standards organization. (The group's initials, MPEG, have become the name for the kind of digital files that result.) "It does indeed lose some of the visual content," says Kaufhold, "but you're going from a 40-foot diagonal movie screen onto a four-foot TV screen, so the average person's eyes will not detect the difference." Laughing, he adds, "Though Martin Scorsese's eyes might."

Encryption then safeguards the files to help prevent piracy, while the final step, digital rights management (DRM), adds another layer of security to prevent unauthorized duplication—in Kaufhold's words, "a wrapper on top of the compression and the encryption."

Crucially, something else can be added to the content during this process: metadata, which is not part of the original audio or video content, but which provides information that can be used by the delivery system or the consumer. Examples of the most basic metadata are chapter stops on a DVD, closed captions for TV broadcasts, and encoded information that tells the playback device which compression system was used and how to set the sound and video.

"You can also add more content to the story, just like they do with video games," says Kaufhold. "You buy a video game disc, and after you've worked your way through the game, it will tell you that there are three more levels available online that they've been working on since they shipped the first disc. You could do the same with an HD-DVD or a Blu-ray disc for a movie. You buy it and play the movie, but maybe the director has some extra stuff he wants to add. Two years later when you play the movie, it connects to the Internet and tells you, 'This character has two more scenes. Do you want to watch them?' With metadata, the DVD doesn't have to be the endgame."

TRANSPORT: From storage, we move to transport. At present, broadcast TV and cable TV can transmit both digital and analog files, while digital-only systems include satellite TV, Telco TV, broadband Internet and mobile TV. The defining stat of each system is its bandwidth—the amount of information, measured in megabits per second (Mbps), that the network can deliver to customers.

Standard definition video, the staple of much of broadcast TV, requires three to five Mbps, with most TV stations having the ability to deliver three or four such streams. High definition, which has twice the linear resolution of standard TV and adheres to standards set by the International Telecommunications Union, uses substantially more bandwidth—anywhere from eight to 18 Mbps. But not all high-definition broadcasts are created equal—different networks use different standards. HD broadcasts from CBS and NBC, for instance, use the 1080i standard, transmitting 1080 horizontal lines of resolution. ABC and Fox use 720p, which contains 720 horizontal lines of resolution and uses proportionally less bandwidth. (Plasma-screen TV monitors generally opt for the 720p standard, while LCD monitors use 1080i.) "Executives at CBS will tell you that Fox HD looks terrible, but to the average viewer the 1080i/720p controversy is probably overblown," says Kaufhold.

Lacking unlimited bandwidth, broadcast television networks have to make choices as to how they allocate their bandwidth. The so-called bandwidth budget gives broadcast networks, which already have the ability to reach virtually every television set in the country, the flexibility to broadcast a combination of HD and SD (standard definition) programming: HD during special programs, the nightly news and prestige events; SD for normal programming.

But the current menu of television providers reaches well beyond broadcast:

Analog cable TV. At present, some 37 million U.S. households are wired for basic analog cable, which offers up to 116 channels and one SD video stream. Dependability is only average and there's no interactivity at present, but the cost is marginal and the format is easy to use.

Digital cable TV, currently in 32.1 million homes, ups the ante with up to 158 channels, and a bandwidth of 38.8 Mbps. The investment is steeper, but digital cable enables the use of video-on-demand (VOD) and digital video recorders (DVRs) such as TiVo, which have become an integral part of many people's viewing habits.

Satellite TV uses multiple 24-MHz channels with a substantial bandwidth budget of 33 Mbps providing mid- to high-quality HD. The equipment cost can be substantial, but dependability is high. It is presently used by 29.5 million households.

APPLE HAPPY: The Apple TV is one of the devices designed to play content

APPLE HAPPY: The Apple TV is one of the devices designed to play content

downloaded from the Internet. Music and video from the iTunes Store

can be streamed to your television. (Credit: Apple)

THE LAST 10 FEET: Once content can move from the Internet to your TV, and

from your TV to your cellphone, a totally wireless environment like this

could be possible. (Illustration by Tricia Noble)

At present, none of those formats allow more interactivity than calling up VOD. But new services that link television with the Internet allow for far greater interactivity. The most advanced systems are not widely available, but several versions of Telco TV, in which telephone companies provide and link television and Internet services, are in the works.

In one version, already popular in Canada and Europe, the telephone company provides all phone and Internet services over a pair of twisted DSL lines. In another, the phone company provides both DSL high-speed Internet and satellite TV. And in the most advanced version, such as the FiOS plan currently offered in San Antonio and parts of metropolitan New York and Philadelphia by Verizon, the phone company installs fiber-optic cable to the home and provides as much as 100 Mbps of data. (A standard high-speed DSL line delivers about six Mbps, while high-speed cable modems are about twice that.)

"It's going to take them a few years to get the fiber out to maybe 20 million homes," says Kaufhold. "It won't reach hundreds of millions of users anytime soon—but when it does, a 100 Mbps connection over fiber basically opens Pandora's Box."

When used in connection with VOD content, for instance, Kaufhold envisions a time when a picky fan of the Seinfeld TV series could pick up a remote, enter "Seinfeld" and "Newman," and call up every episode of the long-running sitcom in which the character of Newman is featured—a task that would ordinarily involve buying DVD sets of every episode and then searching on your own.

"For long-running television series, a video-on-demand service using metadata could offer you just the story line of your favorite character," he says. "Say you've got the complete series of Lost on DVD, and you just wanted to follow the character of Hurley. Well, over the three years the show has been on, there's probably been about a dozen episodes where Hurley's a featured character. But they've been presented out of chronological sequence. So with the video-on-demand service, using metadata to make the connections, you could watch Hurley's story as it was presented in the series—but then you could also go back and watch Hurley's story unfold by having the scenes play out the way they happened to the character. You could reorder them so you see him when he's a young boy, and then you see him working at the Chicken Shack, and then working at the mental hospital, and then winning the lottery, and then getting on the plane and crashing on the island.

As anyone who's spent time on YouTube knows, there's another way to get audio and video content these days: over the Internet. The problem, even with fast connections, is that video files can be so large that loading can be a time-consuming, frustrating process, and high definition eats up too much of the provider's bandwidth to be practical. As a result, users tend to go for shorter, lower quality content that's seven to 10 minutes, at most. Kaufhold calls it "content snacking," and thinks it has permanently affected the user patterns of a younger generation.

The television networks have all recognized the potential in the past year, says Richmond of Broadband Directions. "Just in the last nine months, they've all really ramped up the amount of programming they make available for free streaming," he says. "It was only last October that Disney-ABC formally launched free streaming of their shows, and all of the major broadcast networks followed suit in the fall and spring seasons. They're pursuing that very aggressively, and to the extent that high-quality programming is available, eyeballs are sure to follow."

In an attempt to make high-definition content a possibility, advances are afoot both in the world of streaming and downloading video. Streaming is still used by services like Joost and AOL In2TV. In these services, the video shows on your screen but a copy is never transmitted to your computer. Downloading is more common, though it does also encourage, or at least enable, piracy. Services that offer the downloading of substantial video files include Veoh, which pushes content to a disc drive overnight, so it's available for viewing in the morning; progressive download services like Amazon's Unbox, which enables a viewer to start watching before the download is complete; and peer-to-peer services such as BitTorrent, which utilizes a network of users to transmit files in many different pieces, making it easier for millions of people to watch at the same time.

"The fears over piracy are valid," says Kaufhold, "but the approach the TV networks are taking is let's get our content out there and monetize it with advertising, and make it so convenient and easy for consumers to get it legally that it just defuses the need for the piracy. The idea is they will make legal versions of their content available and easily accessible over many Internet portals, and let the market start to sort itself out."

PLAYBACK DEVICES: Market forces, he adds, are pushing hard. "Everybody's trying to get HD on the Internet. Microsoft and Intel want to make sure that there's a PC in your living room. They understand that the display in your living room is a giant screen, high-definition TV set. And if they want the PC to connect to that, it has got to have HD content. So everybody has sort of drawn the line and said HDTV is the future, and we've got to get there somehow. In the near term, the cable operators and the satellite operators have the advantage, but the Internet's not going to go to sleep on this."

But even when HD is practical and available on the Internet, that'll create another dilemma, this one known as "solving the last 10 feet." In other words, how do you transfer the streamed or downloaded content?

"For now, broadband doesn't allow people to watch downloaded content on their TVs in large numbers," says Richmond. "But it's clear that a lot of energy is going into bridging that gap between the computer and the TV, from Apple TV and X-Box to built-in Ethernet within TV sets. It needs further development, but it's inevitable that movie content will be accessible on the TV—and when it reaches the point where it's viable, there's billions of dollars of consumer spending in home video that'll become available to be shifted over to broadband."

But playing Internet content on your home entertainment system is only one of the problems that need to be solved these days, says Kaufhold. "That's one question: How do you get the Internet connected to your TV set? And then the other one is: How do you get the stuff on your TV to your cellphone? We're going in two different directions—the high-definition TV is your high end in your living room, but then nobody sits in their living room all day. Everybody's out moving around with a cellphone. So at the other side of the equation: How do you get the cool stuff you want to watch from your TV to follow you around on your cellphone?"

That's another question that, for now, doesn't have a clear answer, because the mobile TV market is just beginning to develop. Some mobile solutions are marred by frequent dropouts; others are more reliable but not yet ready for large-scale implementation. As in almost every other area, new markets are emerging, content providers are jockeying for position, and conclusions are difficult if not impossible to draw, even as the eventual answers will affect everyone who creates entertainment.

"There's a Chinese proverb: May you live in interesting times," says Kaufhold with a laugh. "Bingo, we're there. We are in the middle of the interesting times."