BY HOWARD ROSENBERG

Photographed by Michael Kelley

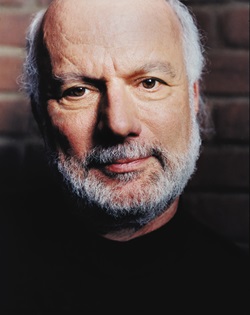

Much of James Burrows’ career affirms that sitcoms, often derided by the narrow-minded snob mob, can be high art. TV’s reigning maven of multi-camera comedy, Burrows accomplishes with actors what other masters have with paint on canvas, helping design characters and a visual style. No wonder he’s in constant demand to direct TV pilots and has been nominated for 21 DGA Awards, more than anyone else on the planet, winning four times.

Much of James Burrows’ career affirms that sitcoms, often derided by the narrow-minded snob mob, can be high art. TV’s reigning maven of multi-camera comedy, Burrows accomplishes with actors what other masters have with paint on canvas, helping design characters and a visual style. No wonder he’s in constant demand to direct TV pilots and has been nominated for 21 DGA Awards, more than anyone else on the planet, winning four times.

Burrows, 66, is the son of Abe Burrows, the famed playwright-director who wrote the book and directed the original Broadway production of How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying amongst other celebrated stage classics. His first job was in 1967 as assistant stage manager on Holly Golightly, an adaptation of Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s headlined by Mary Tyler Moore. It flopped. But the Moore-Burrows association flourished and became pivotal in his career.

He went on to direct The Mary Tyler Moore Show, The Bob Newhart Show and other MTM comedies in a golden body of work that includes the much-worshipped Taxi, Cheers, Frasier, Friends and Will & Grace. There’s a signature look to “Jimmy shows,” as they have come to be known. “I’m not sure it’s a visual look,” he says, “as much as it is energy, a group of people who are very happy with each other, and that comes out on the screen.”

Our recent chat in the Guild’s Robert Wise Library was not our first sit-down together. On a previous occasion he had chided me that a certain TV critic (blush) had forecast wrongly that Cheers would collapse should Sam and Diane consummate their relationship. Obviously, his memory is acute. He also speaks his mind about the business, demonstrating a direct connection between his brain and his mouth.

HOWARD ROSENBERG: Robert Markowitz and Mike Robe lamented in a recent issue of the DGA Quarterly that TV movie directors are undervalued, at least by the media. Does that also apply to TV comedy directors?

JAMES BURROWS: Oh, I think so. The business is writer-driven. The writers are the executive producers, the writers cast it, the writers write the script, the writers make the cuts. And for years we’ve been terribly undervalued. I think it’s fueled by the fact that there are a lot of people thrown into sitcom directing who are not equipped to be directors. They are thrown in so they can become puppets to the writers. That just adds credibility to the claim that we don’t know what we’re doing. And in the last 15 years I have tried to eradicate that problem.

Q: Any bias is hard to break. How can you hope to eliminate this one, which is so deeply entrenched?

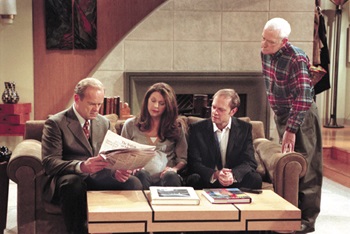

The cast of The Bob Newhart Show: When he was first

The cast of The Bob Newhart Show: When he was first

observing the show, Burrows made Newhart nervous.

(Photo Credit: CBS Photo Archives)

A: By what I do, how I handle a show, what I contribute to a show, the fact that everybody wants me to do a show. And I try to make sure when I work with new writers and new producers I haven’t met before, that they are amenable to what I have to do and what I have to say so that there is a working relationship before I go in there. Writers who say to me, ‘The scene is funny, do it,’ I don’t want to work with. Writers who say to me, ‘I did it because I felt that if he said this at this point, it would be this way,’ I say, ‘Okay.’ I’m interested in a guy like that. He’s defending his work, he’s not being defensive about it. You can’t parrot what’s written, you have to contribute to what’s written. And so I’ve done that and I’ve tried to do it through the DGA.

Q: Did you have this attitude from the start of your career?

A: The first show I ever did was a Mary Tyler Moore when Lou moves into Rhoda’s apartment. We read the script around the table and I said to Grant Tinker, ‘In a sea of danish, I get a bagel.’ I’ll never forget that. It was a terrible reading. The script was a C- and maybe the show was a C. So I use that as an example of what I did in my first show. I quoted Chekhov, I quoted Stanislavsky; I tried to mine a funny pony from a pile of shit. I just did everything I possibly could to try to make the show better. And therefore the actors responded to me, the writers responded to me—not necessarily that I was right all the time, but at least I was in there generating some kind of buzz.

Q: You were still new to the business. Whose example were you following?

A: I learned a lot of that from Jay Sandrich. If you watch in the early days of the great ones, like Sandrich and John Rich, their contribution was enormous to the integrity and to the success of all the television shows they did. I watched Sandrich defend what he thought. And so that’s what I did. I fought as much as I could. I had no clout, but I said what I thought. So I try to advise all directors that, please, there are no rules. When you’re alone with the actors is your time to create. The writer-producers are going to have other notes. If you don’t agree with the note, say you don’t agree with it. Don’t stand on ceremony that the note has to go through you, the director. It’s just not going to work. But you’ve got to contribute. You just can’t be a traffic cop.

Q: Isn’t devaluing TV directors part of devaluing all TV work compared with features? When you want to put down a movie comedy you equate it with a TV sitcom.

A: I think the best comedy being done is being done on television, The Office and Entourage and stuff like that. Sophisticated comedy doesn’t work in movies. I guess Little Miss Sunshine is the anomaly, but that happens very rarely. So for years the best comedy that was being done was being done on television. I mean Cheers and Seinfeld and Frasier. You can’t get that in movies.

Q: Yet TV comedies seem to be on the decline?

A: Right, and I’ve thought long and hard about this. I think the reality show is killing the sitcom. If you watch a reality show, it’s back to the Candid Camera days. People get more amusement watching average people fall down than they do fictional people. There’s some perverse sense of schadenfreude of an average person, your contemporary, getting get hit by a pie than it is a fictional guy, and I don’t know how to overcome it.

HITSVILLE: Mary Tyler Moore was Burrows' first show.

HITSVILLE: Mary Tyler Moore was Burrows' first show.

(Photo Credit: CBS/Photofest)

Q: As the son of Abe Burrows, you must have gone to the theater a lot as a kid. Did you think that was your calling?

A: The first play I ever saw was Jean Arthur in Peter Pan. Then the first thing I ever saw my father do was Guys and Dolls. I went to a couple of rehearsals. I didn’t quite understand it; I was not enthralled with it. I always say that my father was a tailor and taught me how to make a suit, albeit by osmosis. I didn’t quite know what it was nor did I aspire to it, but I went into my father’s business and for some reason I could do it. The acumen was there either in the genes or in watching him. It seems to be a fit for me.

Q: What brought you to television?

A: When I was running a theater in San Diego, I saw this show on the air, The Mary Tyler Moore Show that was a theatrical thing filmed by cameras. And I said, ‘I can do that,’ because that’s what I do. So I wrote a letter to Mary Tyler Moore, who I had known from [the Broadway show] Holly Golightly where we became really good friends, and I got to meet her husband Grant Tinker. When we opened for previews in New York, it was a disaster beyond all disasters. She was crushed and would come off stage crying, and we formed quite a bond. So I wrote her a letter. It was when MTM had gone from Newhart and Mary to four spin-offs, and they had four multi-camera shows on the air so they wanted theatrical directors.

Q: Recalling your days at MTM, Grant Tinker wrote in his memoir that you were initially assigned to observe The Bob Newhart Show and Newhart said something like, ‘Get that guy out of here. He makes me nervous.’ Is that true?

A: I came out in May of ’74, and I watched the Newhart Show. I started in the back row of the stands, and I would watch from there. I kind of understood what the first three days with the actors was. That’s my bailiwick—directing actors. Then when the cameras came in, I would watch intently, and every week I would move down a row. And the fifth week, Bob Moore was directing, who was just a genius, and I knew him. So I came down on stage at some point when there was a break and I said to Moore, I think it would be funnier if Newhart did this or did that. Then I go back up in the stands and, five minutes later, the phone rings. Grant wants to see me in his office. I go up to Grant’s office, and he says, ‘I’m going to move you over to The Mary Tyler Moore Show,’ which was beginning then. I went over there and was introduced to Jay Sandrich. So I guess Newhart was uncomfortable, but we’re good friends now because I did 10 of his shows.

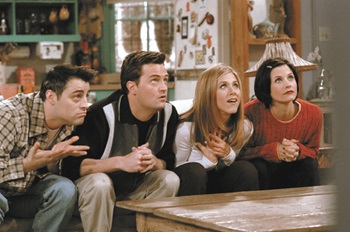

EXPANDING THE SHRINK: Burrows brought more emotion to Frasier.

EXPANDING THE SHRINK: Burrows brought more emotion to Frasier.

(Photo Credit: NBC/Photofest)

Q: What else did you learn from Sandrich?

A: I learned the audacity of saying what you want to say. You know, get it out there. I also learned his swiftness. I also learned his ability to make a decision, that the worst thing you can do is equivocate as a director. If somebody asks you, ‘Should I do it this way or that way?’ pick a way, and if you’re wrong, say, ‘I was wrong. Let’s go the other way.’ Don’t say, ‘I don’t know.’ Don’t say, ‘I’m not sure.’ Just be declarative. Plus, I tried to watch his facility with cameras, knowing the shots he wanted. Because the worst thing you can do on camera day is to have it drag out to where the actors have the sign of torpor and you take the energy out of the show. It took me awhile to get as good as he was with cameras, and now it’s like ridiculous. What used to take me nine hours takes me two.

Q: Do you remember your first day on The Mary Tyler Moore Show?

A: A guy named John Chulay was the AD. He was a great AD who knew cameras, so whenever they had first-time directors on the show he always helped out. And I came in that day and he said, ‘Would you like me to help you with the cameras?’ I said, ‘No, I have to do this on my own,’ and I just plowed through it as best I could.

Q: What was the creative atmosphere like at MTM?

A: It was amazing. I mean—and no disparagement toward the Charles Brothers [Les and Glen]—you probably had the greatest genius in sitcom history, which was Jim Brooks. The ideas in that man’s head—I don’t know where they came from, but some of them were amazing. Plus Ed. Weinberger and Stan Daniels—brilliant. And Dave Davis and Lorenzo Music and Allan Burns—Jim’s partner—and David Lloyd, Bob Ellison, and, in subsequent years, Gary David Goldberg and Hugh Wilson. It was just this unbelievable salon of writers. It was like Paris and the impressionists, and this stuff all revolving around Grant Tinker who would deal with the networks. They would never have access to Jim or Allan. And Grant would sit in there and never give notes. He would say you’re doing a great job. He was really sweet to me and he gave me this opportunity. I was just a little pisher. Although I was 34 years old, I was... you know, I was Abe’s kid.

CALL ME A CAB: After leaving MTM, he moved to Taxi; he says it's

CALL ME A CAB: After leaving MTM, he moved to Taxi; he says it's

the hardest he's ever worked. (Photo Credit: NBC/Photofest)

Q: Taxi was your next major stop after MTM. Was that a difficult adjustment?

A: It was. I’ve never worked so hard on a show. Never. I was still a hired hand. It was a show that was really important to Jim and Stan and Ed. and Dave Davis because they had broken away from MTM and signed a big deal with Paramount. The actors were the most diverse group I’ve ever worked with, still to this day. And it was just monumental. I didn’t know how monumental until I got into it. It was excruciatingly difficult because of the amount of people on the set, the amount of people in the scenes. You had five or six people talking, and four cameras is not enough to cover all of that, so you had to figure out how to cover all the jokes the first time and get all the reactions the second time. And the set was unwieldy: a huge taxi garage that you had to photograph so it looks small. And you had to deal with Jim, who was the writer, starting a movie that he had written, so he was gone a lot. When Jim would show up, he would change stuff that Ed. had changed while he was gone. So the Charles Brothers, who were then the producers, had to wrestle with the writing. I had to wrestle with the directing, and I had to deal with this cast. It was like the bar in Star Wars. It was all of these kind of strange types, and it was my job to make them look like they loved one another and had been with one another their whole lives.

Q: You directed all but 35 of Cheers' 275 episodes. What kind of an experience was that?

A: Well, it could have never happened without my two partners, the Charles Brothers. We met on [The Mary Tyler Moore spin-off] Phyllis in 1975. They were story editors and I was a resident director for the first year, and I met them again on Taxi. Cheers was about the words. We all talked about the idea. We all talked about the characters, and the boys went off and wrote a script. We always knew we wanted to do a show about a sports bar. But now we were responsible, we didn’t have Ed. or Jim or Stan. We were doing this show on our own, so it was our baby, and it was an experience I’ll never forget. It’s still my favorite show I’ve ever done.

Q: What about the logistics of directing the show?

A: Again, it was a huge set. So I hired Dick Sylbert, who was a movie designer. I had worked with him on a feature, Partners, in 1981.

Q: I was going to ask you about working on features.

A: It didn’t work out. I was not cut out for that, that’s not in my wheelhouse, I’m not good with that kind of auteur [approach]. With the movies, you have to have the right magazine on the bed so that when you pan over it—I’m not good with that. So I hired Dick Sylbert for Cheers because I wanted this place to look as good as a bar could look. We wanted people even in areas where drinking was frowned on to want to come to this bar because it wasn’t about the booze. It was about the camaraderie. And then we set it in Boston. Glen Charles called me at 2 a.m. my time, which meant five in the morning on the East Coast, and he was still in a place called the Bull & Finch. He said, ‘I’ve found the bar.’ So we had this downstairs entrance. We had this big, square bar at the center, which made the set seem smaller because it was this huge thing. Then I had that whole hallway behind George Wendt that gave it depth and we had that back poolroom. We had so much more influence than we ever had on Taxi, where we were doing damage control. Cheers was all our ideas, all of our love, all our humanity poured into the show.

Q: Obviously casting was an important part of the success of Cheers.

A: It was sheer luck that these actors were available. We had three couples audition for Sam and Diane: Fred Dryer and Julia Duffy, William Devane and Lisa Eichorn, and Ted Danson and Shelley Long. All three had major plusses. And there were some votes for Fred, some votes for Devane. I think Shelley was clearly the best Diane. And then we said, ‘Let’s go for the upside, let’s go for these two people who seem to have a chemistry together,’ and so we did that.

ACTOR'S DIRECTOR: Burrows with Ted Danson and Shelley Long on Cheers,

ACTOR'S DIRECTOR: Burrows with Ted Danson and Shelley Long on Cheers,

his favorite show. "It wasn't about the booze, it was about the cameraderie.

(Photo Credit: NBCU Photo Bank)

Q: Cheers survived a major change in the show, which is unusual. How did you pull that off?

A: You know, Cheers was, in essence, two shows because when Shelley Long left, we shook up and reinvigorated things because with Kirstie Alley the dynamics changed. When we conceived the show it was always 50 percent bar, 50 percent Sam and Diane, but Sam and Diane were so powerful that the bar took a back seat the first five years. Then when Kirstie came in as Rebecca you got to see how good the rest of the cast was. We went back to our original concept which was to have Sam working for a woman who was like Suzie Pleshette: tough-talking, sexy. But when the boys wrote the script, the character was a total bitch. It wasn’t funny and we didn’t know what was wrong. Then in the third day of rehearsing the first show with Kirstie, Rebecca went to her office and, for some reason, couldn’t get the door open. Everyone started laughing, and as soon as that happened, it became apparent who that character was. You know Kirstie is beautiful, but she also has this ditzy side.

Q: You’ve mentioned self-esteem a couple of times. Was this something that just happened internally or was it the result of the success you had on Cheers?

A: Being the boss really helped, being one of the co-creators. On Taxi, there were fights for what I believed and what I thought. It was always contentious. On Cheers, having the Charles Brothers not fight me, and to have this kind of a very low-key dialogue with them and to have mutual respect for one another, you begin to see that maybe what you have to say has some validity. And I’ve always said to anyone I work with, 50 percent of what I say in my notes is great, 50 percent is shit. It’s not my job to figure out which is which. It’s your job.

Q: Frasier was a different kind of show than Cheers. What was the challenge there?

A: I think I did about 20 episodes. I was wrong about some things and I was right about some things in the pilot. The hardest thing to do and yet the easiest thing to do was to make Kelsey [Grammer] the central character. On Cheers he was a barfly, an obnoxious, pompous shrink. But he was a subsidiary character and what I had to do was make him a central character. In other words, Frasier became Sam Malone and Niles became Frasier. I was constantly on the writers in that first show; I always wanted more emotion when he accepts his father and doesn’t throw him out. Kelsey’s ability, plus my little hand on him, led him to play the center. And so that was my gift. But again, my work is to make the actors feel like an ensemble, so that they have faith in themselves and they know what they’re doing. They should be empowered and not afraid to say what they think.

Q: You’ve said that the experience of working with actors in theater was something you carried with you to TV. How is that?

A: I think it’s all about the story, all about telling the story, all about working with actors. It’s 90 percent of the job. You can learn cameras, you can learn technical stuff. You can’t learn how to talk to an actor.

Q: In a sense, a director has to be somewhat of a psychoanalyst.

A: When the actors go on and on, I have an FM station in my head that clicks in, and that’s what I’m listening to even though it looks like I’m listening to the actors. And it’s good because they want to talk. You let them talk. I try always to include actors in the creative process when I come to the stage the first day of any show, especially the pilot. I have no preconceptions of where the actors are going to end up on the set or anything like that. I say, ‘You start here, and you know, if you feel unhappy there, tell me. I want them to feel part of the process, I want them to create because if an actor creates, he’s going to perform better. If he’s looking forward to something he created, some funny bit, he’ll participate. So that’s what I try to do. If actors are good, I’m going to be good, so I want them to perform and have smiles on their faces because it only makes me look better. But I’ve always treated actors the same way, incredibly deferential.

Q: On an episode of The Comeback [a short-lived HBO series starring Lisa Kudrow as a former star trying to rebound in a new sitcom], you played a director who privately admonished the character for going over your head during a taping and urging the studio audience to lobby for a second take, when you wanted to move on. If that actually happened to you, how would you respond?

A: I would take the actor back—and I’ve done it a number of times—I’d take them back and say, ‘Look, we’re all here to have fun. You’re putting a damper on having fun. You’re being self-indulgent. Don’t do this. Don’t piss me off. Because you make me unhappy, and you don’t want to do that because there is this reputed Fun Clause in my contract that if I don’t have fun on any show, I can leave.’

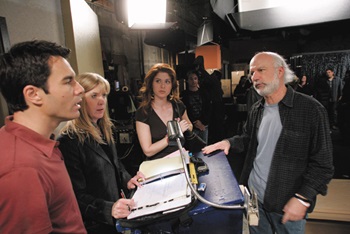

GROUP DYNAMICS: Burrows directed 10 episodes of Friends, including

GROUP DYNAMICS: Burrows directed 10 episodes of Friends, including

the pilot. (Photo Credit: Warner Bros./Photofest)

Q: What about Friends, did you have fun on that?

A: That show was sent to me late in pilot season and I said to my agent, ‘I want to do this show.’ He said, ‘You have no time.’ I said, ‘I’ll work on the weekend.’ I knew how great that script and the cast were. So we read it in front of an audience, got huge laughs. I did stuff on that show that I’ll never forget. In the run-through in front of the audience, there was a warm-up guy and he kept talking. I told him to just keep talking, and then I had the actors start talking upstage. And I said to the warm-up guy, ‘When the actors start talking upstage, you kind of fade out.’ So all of a sudden this conversation was taking place on stage. It was like a stage play and it was dynamic.

Q: Sort of like a dissolve?

A: It was like, what’s going on over here? Oh, these people are interesting. It was just a device to kind of segue the audience into it, and the audience went crazy for that show. Plus, I’ve often said some of the greatest writing ever done on television was done on that show and it was never appreciated until the ninth year. Everybody thought the success of the show was because they were pretty people. I only did 10 of those shows. I know people think I did more. At that point in my life I was forming a company and my company wasn’t involved in producing that show, so I went on to do Caroline in the City and eventually Will & Grace, shows that my company produced.

Q: Speaking of Will & Grace, you directed all 194 episodes of that show, which I think was the first time a single director had done that on a series. Did it ever get tedious? Did you ever find yourself doing it by rote?

A: Never. I was never bored. I’d still had shpilkes before we’d shoot. An hour before I’d go, ‘Oh my God, what if that doesn’t work?’ I still have that. I’m still humble in that way. Let’s see, Will & Grace was in ’98, so I was 58 when I started it, and I did it because it was the funniest show I ever did. I did it because it was working with characters I’d never worked with before. The writing was always funny and cutting edge and an example of how going for the euphemism is always funnier than going for the natural word.

Q: Can you give an example?

A: There was an episode with Harry Connick Jr., and Grace falls down, hits a lamppost and Harry rescues her. And she’s got a big wound. And the next day he sees her and he says to her, ‘How’s your gash?’ [laughs] The great thing about the show was that we got away with all that stuff. It was a fairy tale, it was above reality. All those characters were heightened and it played on that level. I had a great time. I loved knowing that every Tuesday night we’re going to blow the sox off people.

Q: An actor told me recently he prefers single-camera comedies because on multiple-camera shows he can’t control the moment, he has to wait for the audience laughter to end before moving on. In other words, the audience is in control. Do you agree?

A: I do, totally. In single camera, the producers and writers in the room say a joke is funny and then they go on to the next joke. There’s no audience influence. In a sitcom, when you run it in front of an audience, they’re going to tell you what’s funny. So it’s harder to be funny on a sitcom than it is on a single-camera show. I’m not a big single camera fan because you have to re-create the comedy three or four times. I like to hear it once and if it gets a big laugh, ‘Yeah! Let’s go on. Let’s move on. Let’s go home.’

Q: You’ve directed pilots for hits like Dharma & Greg, 3rd Rock From the Sun and many others. What is it you like about directing pilots?

A: I like pilots because I get to work with new characters, new writers, new actors. Although I did one pilot this year with Kelsey and Patricia Heaton [Fox’s Back 2 You], two old warhorses, and that was great. For some reason, after Cheers was over and I started to do pilots I kept getting all the good pilots. I never went after them. They kept being sent to me. And so as far as the passion goes, I never had that. And to thrive in this business, 99 percent of the people need passion because they get the door slammed in their face, and that never happened to me.

Q: Do you take a different approach to pilots than you do to a regular episode?

A: I have a couple more days, which is usually spent with the actors. We try to talk about the show and what it means. You know, about 10 years ago I did a lot of that. Lately I don’t do as much because I don’t have to tap dance for the actors. Right now the actors are so on board with me that they’ll do anything I say. And so I can shortcut a lot of those conversations.

Q: You’ve been quoted as saying one of your goals is to make actors ‘director-proof.’ That sounds almost like you’re diminishing the role of directors. What did you mean?

A: What I mean is that a lot of directors get hired who are not equipped to be hired. It’s one way of me enabling the cast to feel empowered to say what they want to these directors, that maybe they know better. Now, I’m doing it knowing that any director worth his salt can cut through that. But I’m trying to do it because they may be saddled with directors who are not as good and not as empowering and not as creative.

RUN THROUGH: Burrows says Will & Grace, with Eric McCormack and Debra

RUN THROUGH: Burrows says Will & Grace, with Eric McCormack and Debra

Messing, was the funniest show he ever did. He directed all 194 episodes.

(Photo Credit: Chris Haston/NBCU Photo Bank)

Q: Do you have any advice for directors hoping to break into the business or trying to move into sitcoms?

A: My advice is always to go through the Guild and try to observe on shows. You can come and sit in the audience, and there are a number of us who do it, and we’ll talk to you so you can get a feel for what it’s like. So you can educate yourself and see if you want to do that. Learn the ropes, learn how to read scripts—stuff like that. But also it’s really hard because there are not as many sitcoms being done. It’s difficult now.

Q:There’s always talk about ageism in the industry. Even though you have a lot of clout yourself, does that also have an impact on directors? Is there a tendency to look for younger and younger directors because casts and show runners seem to be younger and younger?

A: I think that’s probably true. When I started in the business—and the Charles Brothers, too—we spent seven years on shows before we even ran our own show, so we had some idea of what it takes to run a show. But now you do one good episode and you’re hired to do pilots and everything like that. I think really good directors are important, but the kids think they can do it on their own. They think it’s easy. It’s not easy. The smart ones hire good directors. I would like to think that ageism isn’t a factor, but I think it probably is. But I love working, and I’m out there to dispute all the ageism theories.