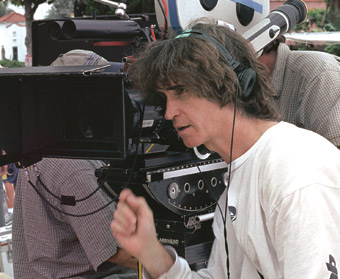

BY JAY ROACH

ACTION: Jay Roach looks like a director, acts like a director, but doesn't always

ACTION: Jay Roach looks like a director, acts like a director, but doesn't always

feel like a director. (Photo by Tracy Bennett/Universal Studios)

I love directing comedies—99 percent of the time. Making people laugh, getting to work with some of the smartest, funniest writers, actors and crews in the English-speaking world—it's all pretty great.

Once in awhile, though, it can descend into a sweaty, anxious hell.

For example, when the script I'm scheduled to shoot that day suddenly gets thrown out as "unapproved" by the stars, by the studio, or by me—which can easily happen the morning of shooting. Sometimes new ideas flow easily and winging it can be exciting. But when the new ideas are being killed off like ducks in a shooting gallery, and I'm burning hundreds of thousands of dollars a day while Robert De Niro, Dustin Hoffman, Barbra Streisand and Ben Stiller stand around waiting for me to hatch a plan and lead the way—that's when I step out to the honeywagons for a minute and start barfing.

The real issue may be that even after directing six films, I still never feel as directorial as I believe I'm supposed to feel. I still don't seem to live up to my own image of what a director should look and sound like on the set.

I refer, of course, to the ability, amidst panic, to convince an entire cast and crew to turn with the director on a dime, to change course as a confident group, in perfect synchronicity, with stunning, organized poetry and grace, like a flock of birds.

I'd like to be more familiar with that sensation.

Everybody knows what directors are supposed to be like. I'm not talking about a riding crop and giant megaphone. For myself, I conjure up the image of David Lean or Francis Ford Coppola (in the suit, not in the shirtless Apocalypse Now photos), or Spielberg and Lucas wearing those hats with the neck flaps on the set of Indiana Jones. Or, in comedy, the smiling, confident eyes behind the glasses of Billy Wilder. I love photos of David Lynch on the set; he seems like a Buddha.

But when I fantasize about what it would be like to command authority just by walking onto a set, I think of Clint Eastwood. I'm told he barely speaks on the set, yet his actors sense what he wants, divine his every intention, and deliver sublime performances. He wraps by 5 o'clock, then it's home to the family, with spare time to write lovely piano scores for his films. He finishes the films early and beautifully, well under budget. And between making these amazing, sublime films, he's off to Maui, or wherever, with an occasional stop-off in L.A. to pick up an Oscar or two.

Dang. That's what I want; I want to get in touch with my Inner Eastwood. It's not like I haven't tried. For a while I thought dressing a certain way might help. I wouldn't start wearing a formal suit like Hitchcock, or even go quirky like Tony Scott with his hot-pink track shorts and cowboy boots, or Wes Anderson with his cool scarves. But instead of my usual cargo pants, T-shirt and hiking shoes, I thought I'd try to find some sort of a "look." Like maybe just wearing all black—black jeans, black button-down shirt, black biker boots. If anybody asked, I'd tell them it was to avoid getting caught in a reflection while directing next to the camera. But I was really just trying to evoke the mystique I never felt—the intimidating power of the dark side.

BRIGHT IDEAS: By being patient and observant, Roach got great comic

BRIGHT IDEAS: By being patient and observant, Roach got great comic

performances from Dustin Hoffman and Robert De Niro in Meet the Fockers.

I experimented with that for a day on Goldmember. It was on the set of Dr. Evil's submarine lair. I was walking the cast and crew through an elaborate establishing shot that craned up over the lair, revealing Dr. Evil's front window shaped like his face, and then over the shark tank, where two huge sharks circled threateningly. But as I was backing up, waving my hands to convey the exaggerated majesty of the shot, I stumbled in my ill-fitting new boots... and fell directly into the shark tank. I went under—which wasn't easy since the tank was only about three feet deep. I climbed out, all black and all wet, to great sarcastic applause and much snickering. So that day's experiment in directorial authority drowned in the shark tank.

Maybe I don't yell enough. I've experimented with directing like more of a dictator. Barking orders. Demanding action. Firing someone to set an example. But I've only experimented at home—alone in my bathroom with the door closed. I couldn't pull it off. I fired myself in the mirror. I've asked around, and I haven't personally found any directors who've succeeded by yelling at anybody. I've met a few producers who use that technique.

Burt Reynolds told me a story when I was directing Mystery, Alaska about a director who tried to order Robert Mitchum to try something he didn't want to do. As Burt's story goes, Mitchum grabbed that director and dragged him by the ankles to a third-story balcony and dangled him over the ledge. Burt told me this story right after I had tried to go directorial on him.

Some directors know how to exploit fear, and intimidate by reputation alone. I once half-seriously asked my great AD, Josh King (who's by far the most authoritative person on my sets, by just being so likeable that people do what he says), to spread a rumor that I was an ex-Navy Seal, with 25 barehanded kills to my credit, and that I'd gone into comedy to escape the horrors of my wartime experiences. Nobody bought it.

The truth is, I don't really need to be "in command." Comedy loves chaos. Improvisation loves flexibility. When you have great actors, a comedy set has to be all about permission to play and freedom to improvise. When I was shooting the big dinner scene in Meet the Fockers, where Roz Focker pulls out the photo album with Greg's foreskin taped to the page, there was so much talking and laughing among the actors around the table between takes, nobody could hear me yell "Action!" Dustin Hoffman, who saved my ass on that movie many times by always breaking the ice and setting the right tone, would invariably break wind or start a great off-color joke just as I was saying "Action!" But it worked. I would just wait, watching De Niro's face tense as Bernie Focker (Hoffman) horsed around. When Bob seemed ready to kill Dustin, or throw a fork, I'd shout louder. "Action!" And we'd be off to a great take, their characters quietly dueling with exquisite tension.

So that's what it's like when it's working. The script is good, and the riffs off of it are even better. I do come up with ideas, solve problems, and make decisions. When it goes too crazy, though, I'll always wish I could be more like Clint. I'll tell myself, "I'm going back out there and I'm going to be directorial. Comedy needs momentum! Comedy needs precision! I'm taking control of this ship!"

Maybe someday.