BY STEVE POND

Illustration by Randy Lyhus

It's hard to shake the old image of the film archivist—you know, the single-minded film buff rooting through basements and rummaging through attics for the last surviving copies of movies, desperate to strike pay dirt before the nitrate turns to dust or the acetate to vinegar. The technical wizard who takes damaged materials shot during Hollywood's early days and restores them to their former glory. The tireless researcher who uncovers lost footage that casts new light on the giants of cinema from decades ago.

And there's truth to that stereotype, because archivists and preservationists are still unearthing early material, still getting damaged goods ready for high-definition (witness the recent restoration of Dr. Strangelove, whose original negative had been destroyed by overuse), still discovering hidden gems in unexpected places (such as boxes of rare footage showing Charles Laughton directing the noir classic The Night of the Hunter).

But those tales, the ones we're accustomed to hearing and telling, are only a small part of what film restoration and preservation has become. The real story of preservation today—a story directors badly need to hear—is just as likely to focus on coping with constantly changing standards, on preserving film, digital data, and all possible combinations of the two. And it's not just about saving the movies from 90, or 50, or 30 years ago; it's about saving the movies that are being made this year.

"Film is an essentially American art form. It's American culture and history, which is why we have to take care of it," says Martin Scorsese, who, with a group of other concerned directors, founded The Film Foundation (TFF) 17 years ago, and has been at the forefront of film preservation for decades. "Also, in a sense films belong to the public, and the owners of the films therefore have an obligation to protect and preserve them."

In this digital age, preservation has moved beyond scouring basements and attics and libraries for deteriorating prints, and beyond shipping palletes of film to archives for storage. There are new concerns, new complications, new strategies that every filmmaker needs to face sooner rather than later.

"There is no single, simple solution to the problem of how to take our moving image heritage and put it into a form that will stay forever," says Robert Rosen, the dean of the Department of Theater, Film, and Television at UCLA, which operates one of the most extensive film archives in the country. "Every solution you come up with uncovers a different set of problems. In the beginning, nitrate-based film was considered an answer to many problems because of its flexibility, but, at the same time, it was chemically unstable and flammable and would eventually turn to dust. When that issue was solved with the coming of acetate film, you had color fading. Once they came up with a low-fade stock, suddenly there was the revelation that acetate film itself deteriorated—the so-called 'vinegar syndrome.' For a brief period, people thought video was going to be the answer, but of course the durability and the image quality no way matched up to film."

He shakes his head. "And now along comes digital, and people assume you've solved all your problems. But, in point of fact, it has uncovered a new set of problems, and a new set of challenges."

Scorsese, who started his crusade when he realized that about half the films made in America before 1950 were gone, now finds himself looking to the future as well. "We have to keep pace with the overwhelming volume of film material," he says. "We have to deal more with recent films, with this extraordinary renaissance of independent cinema from the late '80s and beyond. It's an ongoing process, and it's just going to continue."

Director Allison Anders was converted to the cause when Scorsese showed her a restored print of Douglas Sirk's Magnificent Obsession that revealed details she'd never seen, and then when she saw the mistreatment of her own films. "It's the last thing you're thinking about when you're making a movie," she says. "You think, I want to get my movie made, and then you think, I want to get it out there. You don't stop to think about where it'll be in 10 years—but you have to think about that."

In some ways, the film industry is better positioned to tackle the problems than ever before. Education about the need for film preservation is part of the battle. Here are some of the key players leading the charge:

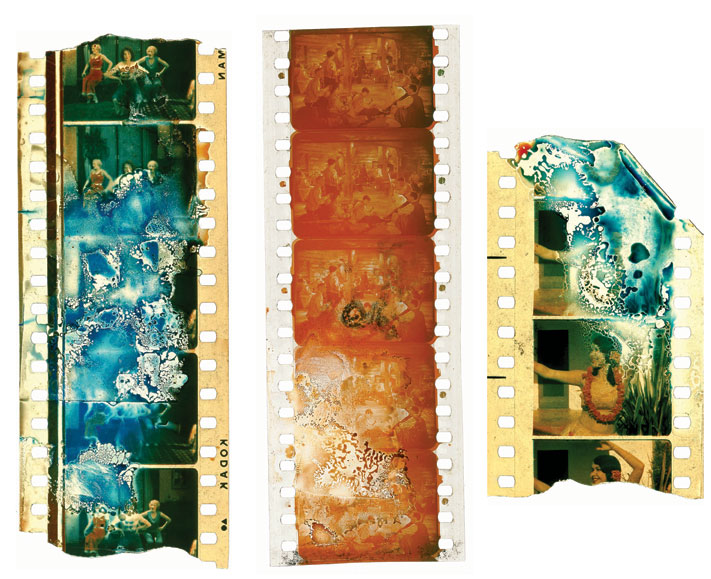

UP IN SMOKE: Extensive damage to the 1920 drama Paris Green, caused by

UP IN SMOKE: Extensive damage to the 1920 drama Paris Green, caused by

the chemical breakdown of nitrate print, was restored by the George Eastman

House through funding by the Film Foundation. (Credit: George Eastman House)

FOUNDATIONS: The Film Foundation remains the leading organization devoted to fundraising, increasing awareness of preservation, and issuing grants to safeguard this country's cinematic heritage. It was begun by Scorsese in 1990 who recruited a group of prominent directors—including Woody Allen, Robert Altman, Francis Ford Coppola, Clint Eastwood, Stanley Kubrick, George Lucas, Sydney Pollack, Robert Redford and Steven Spielberg. They were recently joined on the foundation's board of directors by Paul Thomas Anderson, Wes Anderson, Curtis Hanson, Peter Jackson, Ang Lee, and Alexander Payne. Over the years, the nonprofit organization has funded the restoration and preservation of more than 475 films that were in danger of being lost.

For the last five years, since the merger of The Film Foundation with the Artists Rights Foundation in 2002, TFF has been affiliated with the Directors Guild of America and works out of the Guild's offices in New York and Los Angeles. "It's a natural fit," says the Foundation's executive director, Margaret Bodde, "the Guild exists to protect the rights of directors, and the first, most basic right is for their work to survive—which is our mission. The DGA's ongoing support is invaluable, not just financially, but more importantly in terms of the leadership provided by Marty and the directors comprising our board, two of whom, Michael [Apted] and Gil [Cates], serve as officers for both organizations."

In 1999, independently of The Film Foundation, the DGA negotiated as part of its Basic Agreement with the Motion Picture Producers the creation of the Conservation Collection, requiring that studios provide a new print of films directed by Guild directors to the UCLA Film and Television Archive. "They put that in their contract," says Rosen, "and we're proud of that relationship." According to the Basic Agreement, "the objective in establishing the Collection was the conservation of release prints...so that they may be used as masters should the original film elements not survive in good condition or otherwise to assist in the restoration of films when necessary." To date, the Collection numbers close to 1,000 films and the cost of storing and maintaining these pristine prints is provided by the Guild. The Film Foundation now manages the Collection on the Guild's behalf, which Bodde sees as an important "safety net" in the larger struggle of film preservation.

Archives: UCLA's Film and Television Archive has been rescuing, preserving and showcasing films for more than 20 years, and now has the second-biggest collection of moving-image media in the United States. The archive with the biggest collection, the Library of Congress' National Audiovisual Conservation Center, is in the process of moving into a $150 million-plus complex near Culpeper, Virginia, located in what was once a nuclear bomb-proof underground bunker for the Federal Reserve, and privately funded by the Packard Humanities Institute. Other prominent archives include the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, where Scorsese keeps his extensive personal collection, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Other groups: At the same time, more than 100 regional archives, libraries and historical societies are now represented by the National Film Preservation Foundation, which receives support from The Film Foundation. "The Foundation," says Scorsese, "deals with what we call orphan films: newsreels, home movies, films at libraries and historical societies. There's no telling how much of this material—essential documents of our times—is out there."

Specialized groups have jumped into the business of preservation as well: UCLA, for instance, is involved in joint initiatives with both the Sundance Institute and Outfest to collect, preserve and restore independent films and gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender films, respectively.

"A lot of times these films are made independently, by filmmakers who do not have a lot of resources," says May Haduong, manager of the Outfest Legacy Project. "So our job is to collect all the material we can, make sure the elements are properly cared for, and store it at UCLA. But preservation is not just saving the film; it involves exposing people to it, too."

In New York, the Women's Film Preservation Fund (WFPF) is undertaking a similar task with films in which women played major creative roles. For instance, the 1912 film A Fool and His Money, directed by Alice Guy-Blaché, the first movie made in the U.S. with an all African-American cast, was found in a trunk at a flea market and restored by the Fund. "Hundreds and hundreds of women were leaders in the film industry going back to 1916, when Lois Weber was the highest paid director in Hollywood," says the WFPF's founder Barbara Moss. "Our cultural legacy is at great risk because of a lack of awareness, and we have to make sure their films and their stories do not die."

STRIPPED DOWN: Nitrate film (above) is chemically unstable and eventually

STRIPPED DOWN: Nitrate film (above) is chemically unstable and eventually

turns to dust. About half of American films made before 1950 are lost.

(Credit: George Eastman House)

In this environment, the studios, filmmakers and consumers are more aware of the need for preservation than they've ever been. As video formats and home theater systems become increasingly sophisticated, consumers are conditioned to want the best, the brightest, the sharpest, the loudest.

"There is definitely a greater consciousness on the part of the public of the importance of saving films," says Rosen, who, in addition to his deanship at UCLA, is the chair of The Film Foundation's Archivist Advisory Committee. "The public now values seeing the best possible prints, and they also value knowing something about alternative versions and missing pieces and the differences between director's cuts and various release versions."

And with the ancillary markets now a significant revenue stream, studios have a greater interest in film preservation and the motivation to do so. Studios, which in most cases are the copyright holders of the films, want to protect their assets so they'll be able to sell DVDs, Blu-Ray or HD-DVD discs, and whatever new format comes along in the next few years. Sometimes, the appetite for preservation can be driven by the appetite for profit.

"I've been at the studio for 23 years, and when I started there was not a lot of talk about preservation or restoration by anybody," says Grover Crisp, the vice president of asset management and film restoration at Sony Pictures, one of the more active companies in this arena. The interest, says Crisp, came only after the studio (then Columbia Pictures) was purchased by Sony—which, in contrast to former owner Coca-Cola, had an extensive business selling home video hardware and software. "With Sony's interest in the library to complement their hardware side, they took the opportunity to set up a film preservation program," he says. "We now focus all our energies on the library, on doing lab work and high-definition transfers, all with an eye on the marketplace."

Crisp adds that he involves the filmmakers in the restoration and preservation as often as possible—directors, cinematographers or others who can help bring the work as close as possible to the creator's original intentions. "The films may be ours," he says, "but creatively they're theirs."

Director Barry Levinson learned just how valuable the commercial incentive can be when Sony came to him about a deluxe DVD edition of his 1984 film The Natural. "Because of the original schedule, I never got a chance to do the first act the way I wanted," says Levinson. "And when I tried to get my hands on those materials years later, I was told that all the additional footage had been destroyed. But it turns out that wasn't true, and I was finally able to restore and restructure the film the way I had originally envisioned it."

Which is not to say that Levinson could do the same for other films of his. "On some of my movies, like Tin Men and Good Morning, Vietnam, nothing exists other than the print. And that's frustrating—even if I didn't want to put it back in the movie, it's a part of film history. You don't think about backing up and preserving your elements until you realize what can happen to them."

The good news is that there is now an active, aware network of studios, foundations and archives, and a public that supports the goals of film preservation. But in other areas, the picture is darker. "There are vast quantities of unpreserved, endangered films sitting in private vaults and public archival vaults all across the country," says Rosen. "We are talking about hundreds of millions of feet of film of all kinds."

Gregory Lukow, the director of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress, agrees. "It's still a process of discovery and rediscovery," he says. "There are still lost films being found, lots of films that need to be repatriated from overseas archives, and a great deal of orphan films out there in innumerable repositories."

And while the Library of Congress, for one, is making plans to store all their visual material digitally in the future, everyone involved cautions that digital is no panacea, no easy solution. Rather, it is a format with its own problems. Digital data can be erased or corrupted by careless handling, by magnetism, by a variety of mishaps. In addition, standards and formats in the field change so quickly that a digital film, or the information from a digital intermediate, can be impossible to read after a few years of advances in software and hardware. "It's not as simple," says Crisp, "as taking the data and putting it on a shelf and thinking you can retrieve it five years from now."

Pacific Title, a Los Angeles-based company that makes high-quality film separations for archival purposes, has noticed the problems when the studios send them material. "At least 25 percent of the time recently, our task is not just to make a restoration copy, but also to find the data," says Bruno George, production manager of Pacific Title's Rosetta process. "Material comes up missing, portions of the file can't be read, and we have to go back to other sources at the studio to get duplicate material. We have six preservation projects in production right now where we're waiting for data to come to us, or we've had to recover data before we could deliver the products. It's a pretty big problem, and we're not talking about movies from two years ago—we're talking data tapes that are corrupted, that can't store material after a few months."

BEAT THE CLOCK: The UCLA Archive, the second-biggest in the country, has

BEAT THE CLOCK: The UCLA Archive, the second-biggest in the country, has

been rescuing films for 20 years but it's a race against time to save irreplacable

pieces of our cultural history. (Credit: George Eastman House)

But Phil Feiner, the president of Pacific Title, sees an even greater problem on the horizon. "We have a certain workflow right now in the motion picture business that everybody is used to," he says. "With King Kong, for instance, they shot maybe one and a half million feet of film, and then did all these digital composites. You take that 1.5 million feet of film, and the studio usually puts it on some palettes and puts it in storage. But what happens to the material in the digital composites, and what happens when you start shooting some of these pictures digitally? With Superman Returns or Miami Vice, films that were shot digitally, all of a sudden you have 200 terabytes of data. What do you do with it?"

It will only get worse, he adds, with more sophisticated digital cameras now being tested. "We're going to wind up with more digital features next year. And you have this new 4K digital camera, which will give you exceptional quality—but all of a sudden you're going to have a petabyte [a million gigabytes] of data. That is what I call the 'digital tsunami.' We're all going to be drowning in bits, and nobody in Hollywood is prepared for it. How are we going to store it, what are we going to do with it, how are we going to validate the data? No studio has the systems or infrastructure to ingest and manage that amount of data."

So what's a filmmaker to do? Certainly, directors can't rely on the studios and archives to do the work for them; they need to take an active role in preserving their own work. But there's no easy answer for how to do this today, no way around the fact that many of the digital issues won't be sorted out for years. Still, directors, even ones without big budgets or studio backing, can take steps to increase the chances that their films will survive.

For starters, be aware that preservation is something to think about now, not at the end of your career. "If the steps of making a movie are pre-production, production and post-production, there should also be a fourth step: preservation," says The Film Foundation's Bodde.

Adds Outfest's Haduong, "There needs to be a constant dialogue in every filmmaker's head. They always need to be aware of where their elements are, and aware of problems that can arise. It's not enough to say, 'My elements are at the lab.' Does the lab still exist? And if they go out of business, do they still know how to reach you? It's a pretty frightening thought for a filmmaker, but labs won't necessarily call you if they shut down."

The first rule of preservation, says Rosen, is simple: "Multiple copies, stored in geographically separate locations." If an earthquake hits Los Angeles, you'll still have a copy in New York. "Ideally," he adds, "one of those places should be an archive that will protect your material, a public institution that will not go out of business."

He then ticks off more rules. "It is absolutely essential that you draw a distinction between your master preservation copy and your use copies." He advises directors to resist pressures to use their best surviving copy to show at a film festival, and set limits on how many times they go back to the original materials to make prints. And if possible, have a top-quality conservation copy as well, preferably stored in an archive. One example of that is the Directors Guild Collection at UCLA where prints are stored primarily for conservation. Other archives allow for occasional showings, including Marty Scorsese's collection of prints at the George Eastman House. "You know," adds Rosen, "that in the world there is somewhere, stored under the proper conditions of temperature and humidity, a quality print that will only be used infrequently."

The protocol for storing film is well-established by now. Considerably trickier are the preservation and storage options for digital material, both in the form of work that was "born digital" and in the enormous number of movies that were shot on film but created using digital intermediates.

For that type of material, the rule is to store it in the latest digital format, and then migrate it to the newest format every three to five years. "The only way to deal with digital," says Rosen, "is to copy it, and verify the validity of that copy, on a regular, ongoing basis. The software and the hardware are constantly changing, and there's a pretty good chance that whatever format you put it onto will be obsolete within a few years, unless you keep it constantly up to date."

Still, Rosen and Bodde agree that the best way to protect a movie, even if it's born digital, is to preserve it on film. "There's an increasing realization in the industry that film is still the preservation medium," says Rosen. "It's still more stable and reliable than the digital. But that's not a universal recognition yet, and there may be some extremely valuable products that are endangered because the assumption is, 'Hey, we have the digital materials.'"

The ideal, he says, is the kind of process performed by Pacific Title for most of the Hollywood studios, whereby the digital files are laser-recorded onto YCM separation masters—prints, on high-quality black-and-white Kodak film, representing the yellow, cyan and magenta color separations of the original film. From those separations, Pacific Title then makes a new print, which it compares to a reference print approved by the film's director. "If we do our job," says Feiner, "they should be indistinguishable."

While Pacific Title is working on three dozen studio films, and Warner Bros. and Disney are trying similar processes on their own, Rosen knows that indie filmmakers don't have the resources to go the route of YCM separation masters. In many cases, he says, indie filmmakers overuse the original negative rather than pay for additional materials. Sometimes, the materials that do survive are stored at labs or production companies that have gone out of business or have no particular interest in your film anymore.

Anders knows firsthand how difficult it can be for an indie filmmaker; not only was Gas Food Lodging in dire need of restoration, but she says that all existing prints of Grace of My Heart were destroyed, save for one in Scorsese's collection and one that she located in Europe. "The indies suffer in a particularly bad way," she says, "because they don't strike as many prints, and the ones that do exist get absolutely thrashed. And I could never even afford to own a print of my own movies, because I never had an extra $10,000 sitting around to buy a print." Her suggestion: "If you have disposable income, or if you can put it in your contract, which nobody does, you should make sure you get a print. And if they're not going to give you a print, they should at least give one to Marty, for God's sake."

Still, Rosen says, the principles are the same for independent filmmakers. Don't overuse your original negative...make copies and store them in different places...and if you shoot digitally or use digital intermediates, be responsible for updating and migrating your material on a regular basis.

SAFE DEPOSIT: Directors should make sure they store a quality print under the

SAFE DEPOSIT: Directors should make sure they store a quality print under the

proper conditions of temperature and humidity in a facility like this one used

by the UCLA Film and Television Archive. (Credit: George Eastman House)

"A few years from now, archives will be able to accept those materials and do the periodic migration that is needed," says Rosen. "The Library of Congress is moving in that direction and so are we, but we're not there yet. So basically, you are responsible for copying, migrating, verifying the success of those copies, keeping up with changing formats and changing technologies. The sanguine optimism that I can simply store it away and that's good enough, isn't good enough anymore. There has to be an activist role on the part of the filmmaker, particularly in the digital domain, in overseeing and protecting the materials."

The idea is that not only will the work survive—but that a few years down the line, when a film festival wants to show your movie, it will still look the way it looked when you made it.

"The single best way to make the case for preservation," says Rosen, "is to have audiences fall in love with the images [of a restored film] on the screen, and realize what might have been lost. You can argue the case for preservation abstractly—but concretely, when audiences see that film, they realize the value."

The value he's talking about, he concludes, is not the value of the film stock or the other materials that are so painstakingly preserved. "We're ultimately here because we're concerned about the art form," he says. "We're not concerned about film, we're concerned about movies. Movies are what's important to the culture. They are the artistic expression of our age, and we want them to live on into the future."