BY GARY GIDDINS

(All photo credits: Janus Films)

(All photo credits: Janus Films)

It is no accident that the postwar baby boom produced enough filmmakers, critics, historians, biographers, teachers, and other obsessive fans to populate Rhode Island and then some. No other generation, before or after, was inundated with old movies for free, all day, every day. Million Dollar Movie broadcast the same film 16 times a week, creating countless 9 year olds who could quote more lines from scripts than the scriptwriters. Shock Theater indemnified horror as the most reliably lucrative of film genres; and NBC's Saturday Night at the Movies revived Vertigo, which had died in theaters and is now routinely included on best-ever lists.

True, the films were almost always butchered, often to the point of incoherence. Yet the numberless glitches simply made the process of rediscovering them later in revivals and on home video more enthralling. By then, our horizons were also broadened by movie theaters called "art houses," where we learned that all that glitters was not manufactured in Hollywood. Soon we were soaking up Bergman, Kurosawa, Mizoguchi, Fellini, Truffaut, Antonioni, Buñuel, and Godard—and more often than not their work was introduced with the two-faced logo of a single distribution company: Janus Films.

More than any other company, Janus created the art house market, and had the vision to go beyond first-run releases to create an ongoing repertoire of masterworks. Through festivals, double bills, private rentals, and inventive laserdiscs and DVDs, it created an indelible catalog. Last fall, Janus honored its good judgment and half-century's survival by releasing, through the Criterion Collection, a 50-disc collection, bound in beige cloth and accompanied by a sumptuous 235-page book, as Essential Art House: 50 Years of Janus Films.

M (1931)

M (1931)

With its list price of $850 (the online price at Criterion and other sites is $650, or $13 a disc), the backbreaking carton was not expected to enjoy banner sales. But nearly six months later, demand for it continues. Small wonder: It's like taking your favorite art house—the Thalia, Regency, New Yorker, Little Carnegie, Cinema Rendezvous, you name it—home with you.

Essential Art House is not intended as a celebration of the Criterion Collection; it is a DVD set less taken with DVD accomplishments than with the initial idea of movie repertory. The films are presented as we discovered them in theaters—except that these prints are cleaner and often more complete than those originally imported. The selection, which cannot help but provoke quibbling, reflects Janus' history. None of the signature Criterion extras are included, not even liner notes. The book combines an informative account of Janus by Peter Cowie with unsigned, pictorial glosses on each film in the set. A nice touch is the inclusion of the date and theater of their first screenings in the United States.

Janus' movies made us cosmopolitan in a way literature, music, and painting could not. In spurring the recognition of cinema as art, they inevitably triggered a reevaluation of old Hollywood. L'Aventurra didn't actually make Vertigo deeper, but it did make it more conducive to deeper interpretation. Alfred Hitchcock, who is represented in the collection by two of his British benchmark films, The 39 Steps and The Lady Vanishes, served as a conduit between new wave Europe and Old World Hollywood. Indeed, the set's 10 English language classics remind us that British films were no less foreign than those from continental Europe in their adultness, dry tone and comic sensibility.

The English censors were more daunting than ours, yet could an American studio have turned out a film like David Lean's Brief Encounter, in which there is no sex, violence, language, or immorality of any kind other than the contemplation of adultery? That 1945 film, superbly performed by Trevor Howard and Celia Johnson, remains subversive, dramatic, and involving because it is real, more in line with our own experiences, even in this anything-goes era, than, say Fatal Attraction, with its rabbit-stewing, knife-wielding harridan or Unfaithful with its Mr. Mitty-goes-bonkers husband.

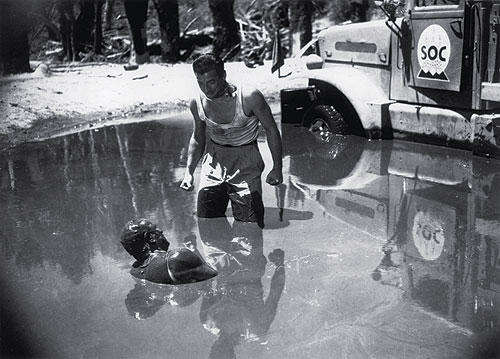

The Wages of Fear (1953)

The Wages of Fear (1953)

For that matter, when has suspense and humor been more evenly mated than in the 1938 The Lady Vanishes? Where are finer, more reverent (yet not obsequious) cinematic adaptations of classic theater than Anthony Asquith's 1938 Pygmalion (Wendy Hiller's Eliza is pure genius, but keep an eye on Wilfrid Lawson's Doolittle), and the 1952 The Importance of Being Earnest (forget the men, and attend to the voices and comic timing of Joan Greenwood, Edith Evans, and Margaret Rutherford)? Who dares a more witting evisceration of military dehumanization and pomp in the guise of wartime propaganda than Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger in the 1943 The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (Roger Livesey and Deborah Kerr at their peak)? To say nothing of the two Carol Reed-Graham Greene collaborations, The Fallen Idol (1948) and The Third Man (1949), which are merely perfect.

The point is that none of the films collected here are dated film-school artifacts, evidence of how far we've come. The literary critic Albert Murray once observed that a writer's ambition and potential could be measured by the writers he or she reads. No serious filmmaker emerging from this collection can fail to swear renewed allegiance to cinema as something more than genre and commerce—in a word, as art. Not that Janus ever distinguished between art and entertainment. You can search its publicity materials in vain for signs of hauteur or pretentiousness.

For sheer nail-biting anxiety, Henri-Georges Clouzot's The Wages of Fear (1953) gives every F/X-clotted adventure film ever made a run for its money. Janus long ago restored 50 or so minutes that had been hacked away for its 1955 American release, but only recently offered a restoration that does justice to cinematographer Armand Thirard's extreme blacks and whites of the penetrating sunlight and sloshing mud. The images glow with immediacy and an almost vertiginous precision, detailing the area in France that Clouzot turned into a South American hellhole. Contending with Akira Kurosawa's 1954 The Seven Samurai (also included in a restored print) as candidate for the most exciting film in the package, The Wages of Fear is as contemporary as Syriana or Blood Diamond as an indictment of colonialist greed, and is more charged than either. Clouzot's film made an actor of Yves Montand, gave Charles Vanel his career pinnacle, and captures the infrequently sighted Véra Clouzot in her most enchantingly sexy role.

The Seventh Veil (1957)

The Seventh Veil (1957)

We are besieged, on a weekly basis, with television shows and movies about serial killers, most of them retailing the same story and forensic grossness. Why the subject has become a generic staple is a subject for anthropologists, but the two great works in the idiom are in Essential Art House: Robert Hamer's 1949 Kind Hearts and Coronets, in which Alec Guinness is slaughtered eight times as eight different victims, and Fritz Lang's 1931 M, a breakthrough in the use of sound with its overlapping dialogue and long silent passages. This film, which made Peter Lorre an international star (though an ill-used one when he relocated from Germany to Hollywood), has miraculously not dated at all. The killer's defensive howl, the baffled police, and vigilante citizens (in this instance, the criminal underworld) are thoroughly contemporary—except for the absence of gore and moral certainty. M also has one of the great tracking shots: two-and-a-half minutes, as the camera explores a beggar's lair and then passes through a window grating.

A word must be said of Ingmar Bergman, whose films were most important in launching Janus and the art house movement of the late-1950s. He is represented here by three films that brought him worldwide renown: Wild Strawberries, The Seventh Seal (both 1957), and The Virgin Spring (1960). The combination of high-contrast black-and-white cinematography with extreme close-ups—a stylization that, in this country, reached a belated apogee in Raging Bull and recently enjoyed a surprise revival in Good Night, and Good Luck—presented a Nordic glory, doing more to advance a Scandinavian aesthetic than anything since the 1890s novels of Knut Hamsun. The gleaming, inky, fixed look of Bergman's images, and the relentless discussion of humankind's prospects in an indifferent universe, convinced countless would-be filmmakers and film lovers that the potential of movies was unlimited. Despite occasionally sluggish pans, lapses in logic, and repetitive "wither God?" meditations, they remain visually ravishing (no director had produced more museum-quality still-frame images), psychologically astute, symbolically deft, and stubbornly fixated on the religious-ethical concerns that haunt our existence.

Essential Art House is a luxury object, but perhaps only those who cannot quite take DVDs for granted, who are still amazed by the idea of loading legendary films onto a television or laptop, can appreciate the frisson of flipping these heavy cardboard leaves. Each page contains four films, triggering recollections of the movies and of the circumstances in which you first saw them. The images collide in your head: the burst of color and music in Black Orpheus; the abrupt dressing-down of a tubercular soldier in Fires on the Plain; the secret homage to Balzac in The 400 Blows; the heartbreaking Dita Parlo in Grand Illusion; the grotesque Serafima Birman peering into the camera in Ivan the Terrible, Part 2; and on and on through the last supper burlesque of Viridiana and the Emma-Bovary-meets-Mack-Sennett breakdown of marriage in The White Sheik, all of it encouraging us—as the cynical squire, Jons, says in The Seventh Seal—"to feel to the very end the triumph of being alive."