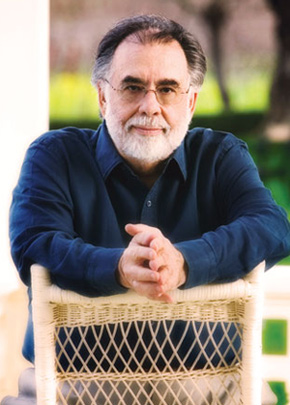

BY SCOTT FOUNDAS

Photographed by Mark Estes

Has any American filmmaker ever enjoyed a four-picture run to rival that of Francis Ford Coppola? From 1974 to 1979, starting with

The Godfather, followed by

The Conversation,

The Godfather Part II and

Apocalypse Now, he garnered four DGA nominations and two awards, as well as 10 Oscar nominations and four wins. He was the first boy wonder of the film-school generation, the artistic visionary who wedded the best aspects of classical Hollywood narrative to the bold currents of the New American Cinema and irrevocably altered the face of modern movies.

Those landmark achievements haven’t aged a day in 30 years, so it’s startling to realize it’s been a decade since his last film, The Rainmaker. By the late 1990s, it was possible to feel that Coppola had given up moviemaking altogether, turning his attention to a different kind of show business—wine, hotels and a literary magazine.

But even when Francis Coppola has been out of the movie industry’s sights, he has rarely been out of mind. Now he is returning with two new film projects that represent the kind of intimate, personal visions he always dreamed of bringing to the screen before the Corleone family got in the way. The first, Youth Without Youth, which Coppola shot in relative secrecy in Romania in 2006, is an adaptation of a short story by controversial author Mircea Eliade about an elderly university professor who begins aging backwards after getting struck by lightning in pre-WWII Europe. The second, Tetro, is a multigenerational chronicle of an Italian immigrant family (not unlike Coppola’s) living in Argentina and is scheduled to begin production in Buenos Aires later this year. One week after the first private screening of Youth Without Youth, Coppola was in good spirits and talked about his long and varied career and his own artistic rebirth.

BACK TO WORK: Coppola directs a scene at a Nazi checkpoint in

BACK TO WORK: Coppola directs a scene at a Nazi checkpoint in

Youth Without Youth, shot in Romania. Making it reinvigorated

him, which, he says, is exactly what the film is about.

(© American Zoetrope)SCOTT FOUNDAS: You’ve just completed Youth Without Youth, your first new film in 10 years. How does that feel?

FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA: So far, I’ve screened it only one time—it was a private premiere for about 120 people, mostly film directors. The reaction was beyond my expectation. I’m still trying to digest the possibility that it went over as well as it seemed to. But from the reactions of those people who talked to me afterwards, I gather they took it as an unusual film and were very positive about the fact that I would do something that you can’t immediately throw into a particular genre. They really took it the way I’d hoped they would, which was as a piece of new work that’s trying to blaze its own way forward. But you know, with films you don’t really know for a while what in fact you’ve done or how it’s going to be perceived. Sometimes, you don’t know again for 20 years.

Q: In the online diary you kept during the production of the film, you talked about artists who achieved their greatest success early in their careers, only to spend the rest of their lives unsuccessfully trying to equal or surpass it. Then you wrote, ‘I’ve begun to think that the only sensible way to deal with this dilemma is to become young again...’ Does this mean you feel like a kid starting out all over again?

A: I feel as though I’ve made a deliberate choice to reapproach filmmaking with the same attitudes and ignorance that I had as a young person. Obviously, I’m not a kid, but we all have a kid in us and I approached this movie with the willingness to do whatever came into my mind. Going back to theater, when I was about maybe 15, I got my hands on a paperback copy of A Streetcar Named Desire, and I remember being very moved and impressed by it. It may have been one of the first more adult things I attempted to read. Then I read other plays and I got this idea that I wanted to be a playwright. So, I tried to write some plays and some short stories, and I was very worried about the fact that I didn’t have any talent. The truth is that playwriting and writing itself is very difficult, but if you do it relentlessly and don’t give up and make writing a regular part of your life, eventually you get better. I even went to Hofstra College on a little playwriting scholarship, but I still thought my stuff wasn’t very good, which is why I ultimately made the transition into directing.

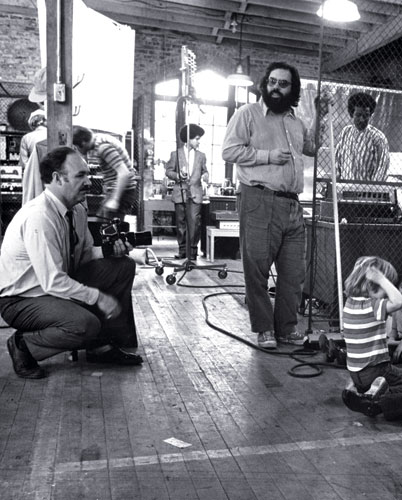

TALKING PICTURES: The Conversation (1974), with Gene

TALKING PICTURES: The Conversation (1974), with Gene Hackman, was one of Coppola’s smaller, more personal

films that resembled European movies of the ’50s.

(© DGA Archives)

Q: So how did you come to make the transition from theater to cinema?

A: Around my third year at Hofstra, I was walking on campus one afternoon and passed by this building called the Little Theater. There was a sign that said, “Today at 4:30: Sergei Eisenstein’s October, or Ten Days That Shook the World.” I had nothing better to do, so I just stayed there and saw it, and when it was over, I was so knocked out by the film that I just said, ‘Well I’m going to make movies.’ Up till then, I was pretty much one of the star theater students, and I was hoping to go to Yale graduate drama school, but that afternoon I decided that I wasn’t. My brother was going to UCLA at that time, and I had spent a summer with him out there once. So I decided I would go to the UCLA film school, and a year later I did.

Q: Around this same time, you went to work for Roger Corman. How did that come about?

A: There was a notice on the billboard that Roger Corman was going to be interviewing some UCLA students to work on a specific project. I answered the ad and ended up getting the job, which was to take two Russian movies Roger had bought and dub them into English—or, since I couldn’t speak Russian, to make up stories for both of them. Of course, Roger wanted to make them into films he could release. It was insane, but it was a wonderful apprenticeship.

Q: How did you get to direct your first film for Corman?

A: Roger hired me to be his assistant. He would have me go to the set in the morning when he was shooting a movie and be the dialogue director, rehearsing the actors and even pre-staging some scenes. But by 1 o’clock, I’d have to go back and do my grunge work. At one point, Roger told me he was going to make a film in Europe and asked me if I knew a young guy who knew how to record sound, so I just got the book about the recording machine and read it and said, ‘I can do it, Roger.’ Then I went to Europe with him when he did this film called The Young Racers. Now, it was well-known that usually when Roger brought people and equipment to Europe that were paid for by AIP, often he would use all of that stuff to make a second film for his own company. At the end of The Young Racers, he had to go back to the U.S. to make The Raven. I tried to come up with an idea that would convince Roger to let me take the equipment and make a movie, and that turned out to be Dementia 13.

CHEEK-TO-CHEEK: One of the reasons Coppola wanted to do

CHEEK-TO-CHEEK: One of the reasons Coppola wanted to do

Finian's Rainbow (1968) was to impress his father because Fred

Astaire was in it. (© AMPAS/Warner Bros.)Q: Throughout all of this, did you feel like you were finding your own voice as a filmmaker?

A: Making movies was such a pipe dream! I was just having fun. From my theater experience, I could build scenery and do lighting. I was pretty good at technical things; I used to like to fiddle around with electrical devices. So I had these more practical skills that I was using to prop me up. I could also write, and I found that, even though I had always lamented that I had no talent, all of those nights and mornings of trying to write had given me a little bit of a technique. When I made Dementia 13, I was astonished that it would even pass muster as a movie, but now when I think back on it, it did have the beginnings of a style and was a real movie—sort of.

Q: Although it’s a film that tends to get overlooked, Finian’s Rainbow also shows a lot of style and innovation, particularly in regard to some of its editing and the mixing of location shooting with studio work.

A: Finian’s Rainbow was an extraordinary opportunity for a young director. I had done a lot of stage musicals, so I had experience with the genre. I tried very hard to get them to let me make the whole movie on location in somewhere like Tennessee, where I could have staged dance numbers in a real setting. Because while Finian’s Rainbow has one of the most beautiful scores ever written for a musical, it also has one of the dumbest books which dealt with an early version of civil rights issues. So, I thought that if I could put it in a real setting, I could pull it off. As it is, I think the movie is fine, but I left it to the producer and others to finish it after I had done a preliminary edit and went off to make The Rain People. Now when I look at Finian’s Rainbow, I think my only dissatisfaction is that I feel I could have greatly improved it if I had done the final postproduction. I might do that someday just for the fun of it—not to ever show it, but just to amuse myself; to see how good I can make it.

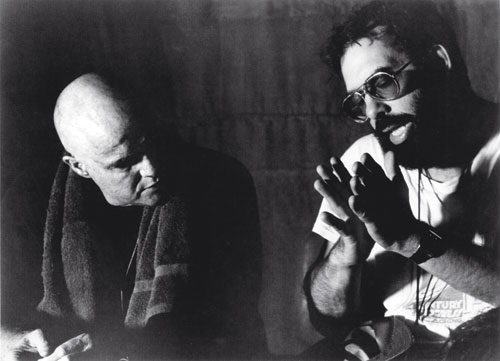

EXTREME PREJUDICE: Coppola with Marlon Brando in

EXTREME PREJUDICE: Coppola with Marlon Brando in Apocalypse Now (1979). (© AMPAS)

Q: Then a little movie comes along called The Godfather, which at first you didn’t even want to make. What changed your mind?

A: After The Rain People, I had gone off to San Francisco and founded American Zoetrope, which was supposed to be an American independent company, like a mini-United Artists. I was affiliated with a lot of colleagues from film schools, both UCLA and USC, including my closest colleague at the time, George Lucas. We had a lot of dreams about making the kind of films we had been seeing in the ’50s coming out of Italy and France. We didn’t want to make big, schmaltzy American movies. But at that point, we were in deep trouble, and, for some reason, Paramount called me up. They owned this book called The Godfather, which was starting to become popular, and they thought they’d hire an Italian-American director because that might bring some authenticity to it, and a young director because he might be easier to push around and would able to make the film for less money. Now, if you read the book of The Godfather, you realize that the story that makes up the movie is one part of it, but there’s another very big part that’s more salacious, more like an Irving Wallace novel. And when I started reading it, I thought it was cheesy and I didn’t want to do it. Ultimately, it was George who said, ‘Francis, the sheriff’s going to put a chain on the door of Zoetrope. We have no money. What are we going to do?’ So I finally accepted The Godfather. It wasn’t a great deal: They offered me two possibilities, one of which was very little money plus 10 percent of the movie, or a little more money but only 6 percent of the movie. I needed to have some money right away, because by this time I had two kids and a family and we were in debt, but I said I wanted 7 percent because that was my lucky number, and they said, ‘Sure.’ But they never gave it to me. They gave me 6 percent, which of course turned out to be a lot of money.

Q: This moment in American moviemaking—the late ’60s through the mid-’70s—and its supposed freedom of expression has been heavily mythologized in recent years. But at the time, you were quite open about your difficulties in dealing with the studios and your desire to be able to work independently of them.

A: I don’t think there was such a real atmosphere of freedom. I think there was a transition happening and the studios themselves were beginning to be acquired or going through financial difficulties and they didn’t know what movies to make anymore. They weren’t sure what the audience would go for. So in a way, for our generation that supposedly flowered in the ’70s, if we had freedom it was because we seized it, not because it was handed to us. We just tried to be as tricky as we could and to outmaneuver them. The exciting beginnings of that were in movies like Bonnie and Clyde, which Warren Beatty had managed to pull off using his charm and the fact that he was a movie star. To us, Bonnie and Clyde was a great achievement. Then The Godfather did extremely well financially. So it was an accident, really. If the studios then were as well-organized as they are today, I don’t know that it would have happened.

VEGAS NIGHTS: Coppola with DP Vittorio Storaro on

VEGAS NIGHTS: Coppola with DP Vittorio Storaro on

One From the Heart (1982). (© American Zoetrope)Q: The style of The Godfather is lush and expressive as opposed to The Rain People, which is gritty and naturalistic.

A: When I took the job, I spent six weeks or so just analyzing the novel. I created what we call in the theater a prompt book, where I literally dissected the novel and tried to find the core of every scene. I ended up concluding that it was the classic drama of a father and several sons; it could have been a Shakespearean play. Out of that study, I came up with the idea that I would do the film in a very classical way. When I chose the various collaborators, including the great Gordon Willis, [production designer] Dean Tavoularis and [costume designer] Anna Johnstone, we spent an entire day discussing the style of the picture and out of that discussion came all of the ideas for what was really the style of The Godfather—the fact that it would exist in extreme levels of darkness and light; that Don Corleone would be in his den in this kind of black ambiance, and it would be intercut with the wedding outside which would be bright; that the camera would rarely move and instead the actors would move within the fixed frame, like a picture frame almost.

Q: You mention the crosscutting during the wedding scene at the beginning of the film. Even more groundbreaking—and often imitated—is the cross-cutting from the movie’s baptismal climax.

A: When you adapt any novel for the screen, you have to find ways of expressing what’s in the book that are quicker, more condensed. In regard to the ending of The Godfather, when Michael Corleone takes revenge against all of his enemies during the baptism, that went on and on for pages and pages, and I thought maybe a way I could do it all in some sort of filmic manner was through this crosscutting technique. So, it started out as a practical solution: How do I manage to tell this story that’s so big and broad and wide in two hours and 40 minutes of screen time, and how can I use the language of film to take what was 60 pages in the novel and make it into three pages of the screenplay?

Q: The cast of The Godfather was nothing if not a diverse mix. How were you able to work with everyone to create such a convincing sense of family relationships?

A: Being a theater-trained person, I knew how to rehearse and how to use improvisation. One of the most important improvs we did with the cast was just having them have an Italian-style dinner with everyone sitting in the places they would, around the patriarch. Marlon just came and sat there. My sister Talia [Shire] was serving the food. Al was being very quiet, waiting for people to pay attention to him. Jimmy Caan and Bobby Duvall were doing Brando impersonations. The great actor John Cazale was being so sweet-natured. And pretty soon, everyone just fell into character. On The Godfather Part II, we did an even wilder improvisation where we rented a compound of houses on this lake and we did a 24-hour improvisation where everyone was in character from the minute they got up in the morning to the minute they went to bed at night. I’d learned from working in theater ways to prepare actors and give them the relationships that you want. I always tell young directors that if they have time to do rehearsals, don’t just sit the actors in a room and have them read the script.

READY TO RUMBLE: Coppola with Matt Dillon and Dennis Hopper in

READY TO RUMBLE: Coppola with Matt Dillon and Dennis Hopper in

Rumble Fish (1983). (© Universal Pictures)Q: After the success of The Godfather was there a lot of pressure on you to make a sequel?

A: When the movie turned out to be an enormous success, Paramount wanted to do a second one, and I didn’t know how you could do that. It seemed to me like a pretty complete drama, and it had been a terrible experience. In fact, after the head of Gulf & Western asked me so many times, I said I wouldn’t do it but that I would help them; I would be like a producer and would choose a young director who could do a second Godfather. I chose Martin Scorsese, and this is when he had only done a couple of pictures, and they said absolutely not, and then they said basically, ‘Name your own terms.’

Q: But in between the Godfathers you were able to make a smaller, more personal film you said you always wanted to make: The Conversation.

A: That’s what relates to me now, which is that The Godfather sort of interrupted my career, because I’d always wanted to make a series of films from original screenplays, more in the spirit of the European pictures of the ’50s, but also of the great writers, like Tennessee Williams and Eugene O’Neill. I wanted to be someone who, when a new movie of mine came out, it would be something no one had ever seen before, because it would have just been written and created. Today, every time a movie comes out, it’s pretty much like something else you’ve seen; it’s deliberately that way, because the studios don’t want to go out on a limb. We no longer have the kind of culture in which there are artists whose new work we’re anxious to see. Even with most of our best directors, we know they need to be sponsored and financed, and that this pretty much means making a movie that the studio wants you to make because they think it will be a hit. I wanted not to be that way. I wanted to do one film after another like The Conversation, and, in a sense, you could say that Youth Without Youth is the film I made after The Conversation.

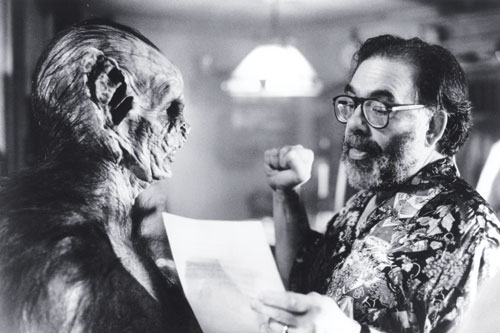

INTO THE NIGHT: Hanging out with a friend on Dracula (1992).

INTO THE NIGHT: Hanging out with a friend on Dracula (1992).

(© DGA Archives)Q: Is it true that the complex flashback structure of The Godfather Part II is something you arrived at only relatively late in the postproduction process?

A: It’s true that I began to understand the structure when I had the movie fairly well assembled and we were showing it to audiences. What I realized was that, in the script and in the way it was being cut, there were two parallel stories—the story of the father as a 30 year old and the story of the son as a 30 year old. The film would proceed with one story and then, at a certain point, it would go and tell the other story. The two stories were like two train tracks laying side by side. But I realized watching it that the audience needed more time to get with each of the stories. So, rather than going for 10 minutes with one story and then breaking off and going for 10 minutes with the other story—which is the way it was originally—I just decided at one point to double things up, we’d stay for 20 minutes. My feeling was that the audience needed more time to really follow either of those tracks before you would interrupt one to go to the other.

Q: You’ve always been very open to the use of new technology, and even predicted, long before anybody would have believed it, the onset of the digital revolution.

A: It’s true that I had that embarrassing moment on the Oscars, the year that Michael Cimino won for The Deer Hunter. Before I gave him the award, I looked at the audience and said that there would be a whole new evolution of cinema. That it was going to become electronic; that things were going to be possible that they couldn’t even imagine would be possible. But that underneath, as long as there was human talent guiding things, it would all be okay. Nobody knew what I was talking about, and I was much ridiculed for what I said, because it was off the wall. But it has all happened.

Q: Obviously, this interest in technology reached something of an apotheosis with One From the Heart, for which you bought your own studio and originally conceived of shooting ‘live’ to film.

A: That was right in the concept from day one. The studio I’d bought and the whole idea of going back to the studio system was with the caveat that it would be an electronic studio and that we would be able to make movies live. There would be such a thing as ‘live’ cinema, and it’s one of the very few regrets I have in my life that as we got closer and closer to production, the cinematographer, Vittorio Storaro, who was my dear friend, came to me and said we should do it one camera at a time. Both he and the art director wanted to make more sets and shoot one camera at a time, because you can light one camera more beautifully. I wanted to make it in the spirit of what John Frankenheimer was doing on television in the ’50s. Go and check out the film he made with Mickey Rooney called The Comedian and realize that it was done live. It’s not a filmed play; it’s a movie! That goal still exists, and it’s heartbreaking to me that I came so close, that I had all the means, and that basically these people who pressured me to not do it were my friends and they were scared. That’s also why I went broke, because by doing it one shot at a time, then it had to be edited. Whereas if it had been done live, it would have been edited in the camera and I would have saved myself from bankruptcy. I don’t mind so much the bankruptcy part, during which I lost the studio—which was a wonderful studio—but what I do mind is that I came so close to realizing this wonderful experiment of making live cinema.

CRIME PAYS: At first, Coppola (seen here with Marlon Brando) didn’t

CRIME PAYS: At first, Coppola (seen here with Marlon Brando) didn’t

want to direct The Godfather (1972). (© AMPAS)Q: Several of the films you made following the failure of One From the Heart have an old-fashioned studio feel, like The Outsiders.

A: I’ve always believed that every movie has a theme and that the style of the film ought to be something that comes out of this theme. In the case of The Outsiders, Gone With the Wind was the book the kids in the movie were reading, and it too was a big romantic story of youth, so I made the movie in the style of Gone With the Wind. Rumble Fish was very different—it was the antithesis. Rumble Fish was made as a black-and-white, almost art film for kids.

Q: The films you directed in the ’80s and ’90s tend to be regarded by many observers as ‘for hire’ jobs that you took just to pay the bills. But even in these films, it is possible to see some of your recurring themes and motifs.

A: One From the Heart left me with an enormous financial hole and I was able to retire that debt, rather than losing my home and all of my property, by making one film every year and paying off an enormous annual repayment to the bank. But even when I was in that mode, I always tried to find something to fall in love with. With Peggy Sue Got Married, for example, I finally realized that I could take something from Thornton Wilder’s Our Town and apply that to the film. Certainly, Tucker was kind of how I felt about myself, trying to bring innovation to an industry that didn’t want it. Dracula was another attempt to shoot a movie entirely on soundstages. A lot of people don’t realize it, but every shot in that movie was done on a stage. So I never made a film where I couldn’t tell you what it was that made me fall in love with something about it. Some worked better than others, but when you’re making a movie every year because you have a payment coming up, it’s a unique situation. But even then, I continued with my idea of, every time I made a film, asking what was the theme and doing some kind of experiment that I could learn from.

Q: What made you become disenchanted with the business?

A: In those days, every film was an experiment, and I imagined that someday I would apply everything I had learned to a career of making original films from original screenplays. Then I reached the point where I just decided to stop making movies altogether because the business was getting more complicated. The new companies were much more controlling and the showmen of the past—as tough and vulgar as they had been—had been replaced by corporations. The kind of movies I wanted to make was now virtually impossible to get financed. I realized that the movie business wasn’t really even a business for anyone but the distributors, because the money all gets dumped into their hopper and then they pay out how they wish. So I decided to go into a different business entirely to make a living and hoped, at some point in the future, I’d be able to pick up my work again and have the type of filmmaking career that I’d always wanted.

JURIS PRUDENCE: Coppola with Matt Damon in The Rainmaker (1997).

JURIS PRUDENCE: Coppola with Matt Damon in The Rainmaker (1997).

(© Philip V. Caruso/Paramount Pictures)Q: In this decade that you’ve spent focused on your other businesses, have you still been able to find the same kind of creative satisfactions you once took from making movies?

A: There’s a little bit of a misconception there. There were 10 years during which I was focusing on the wine business, the resort business and these other businesses, and indeed those are all very creative pursuits—they’re all a form of show business. But, at the same time, I was very much involved writing three projects that ultimately hit dead ends for different reasons.

Q: So how did you come to make Youth Without Youth?

A: Finally I made a decision inspired by my daughter Sofia, who had gone off to Japan and made a low-budget film called Lost in Translation. I just realized that maybe I should go off on my own and make a movie I could finance myself and not tell anyone about it and not show anyone the script, not announce it, not anything. And ultimately that’s what I did. It spoke to me, not only as a film I could finance myself—it’s not a small film, it’s an ambitious film, but it’s not a $100 million film—but as something that inspired me like those wonderful films of those directors I admired. And that gave me a new life, really. In a sense, I was reinvigorated, which is exactly what Youth Without Youth is about.

Q: Did you shoot Youth on DV?

A: I shot both film and digital. But my feeling, to be honest, is that it’s totally irrelevant and I would prefer not to say exactly how I did it until people see it. In a time of transition, when people are so uncertain about the medium of cinema, I don’t want to really disclose. I did some new things—let me put it that way—so people should see the movie and judge the visuals of it without me saying how I did it. And then I’ll say how I did it later.

Q: You were honored with the DGA Lifetime Achievement Award in 1998. Could you talk about your history with the Guild and the role it’s had in your career?

A: The Directors Guild was a particular guild in my life that I found most worthwhile, especially in the sense of camaraderie it fosters with the other members. In fact, when my own children—my daughter Sofia and my son Roman—began to make films in a very low-budget area, they asked me if I thought they should join the DGA and I said, ‘You know, deep down you have to, because the DGA is a wonderful institution of which I am proud to be a member. And Dorothy Arzner, my teacher, was a member.’ I find the DGA very positive and very sweet-natured, and I am very grateful for the way they have embraced me as one of their now older members.

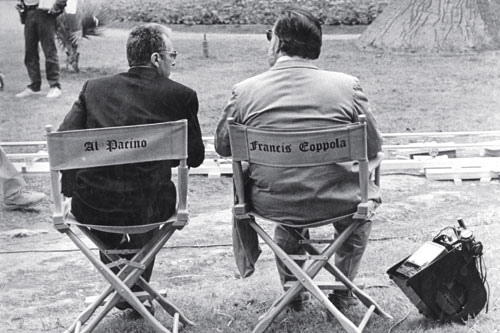

THAT'S A WRAP: Al Pacino and Francis Ford Coppola on the set

THAT'S A WRAP: Al Pacino and Francis Ford Coppola on the set

of The Godfather Part III (1990). (© DGA Archives)Q: So, as one who has been so prescient when forecasting the future of movies, where do you see the medium headed in the next couple of decades?

A: In terms of the kinds of movies, I think you should watch what I’m doing, because I think that’s what other people want to do, too—to make personal movies. Youth Without Youth is me getting to make a type of film that is not based on formulas and not based on previous movies that did well, or a sequel to something. I think a lot of directors would like to go their own way if they could figure out how to finance it. If our greatest filmmakers can do what they want to, then you’ll have a golden age. Regarding where the films will be seen, clearly there are multibillion-dollar interests at stake trying to figure that out right now, because they want to be there when it happens. They would have people watch films on their cell phones if they thought they could make a fortune from it. Whether the cinema is best served to be watched in an airport on a cell phone is another question, and I would hope that the captains of industry will ultimately guide the cinema toward what will best fulfill the audience’s needs. Of course, I love to see movies on a big screen with a great soundtrack, and I hope that experience isn’t ultimately lost simply because there’s no money in it. Unfortunately, most of these decisions are going to be determined by economics, and I only hope that the audience—the film lovers and the cinema goers—will stand up and demand a quality experience for what has become the most important art form in our time.