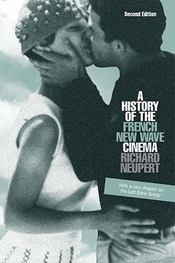

(University of Wisconsin Press, 424 pages, $26.95)

By Richard Neupert

Previous surveys of the French New Wave have tended to concentrate on the five young critic-directors who emerged from Les Cahiers du Cinema. This approach isolated these filmmakers from the diverse traditions that nourished them and the filmmaking establishment that infuriated them. Thus James Monaco’s otherwise excellent The New Wave (1976) suffered from a lack of deep historical-political context, while Roy Armes’ French Cinema (1985) similarly saw the New Wavers as lacking forebearers or descendants. That all changed when Richard Neupert published A History of the New Wave in 2002, the first comprehensive overview in English, and now, in this expanded second edition, surely the standard work on the subject.

Previous surveys of the French New Wave have tended to concentrate on the five young critic-directors who emerged from Les Cahiers du Cinema. This approach isolated these filmmakers from the diverse traditions that nourished them and the filmmaking establishment that infuriated them. Thus James Monaco’s otherwise excellent The New Wave (1976) suffered from a lack of deep historical-political context, while Roy Armes’ French Cinema (1985) similarly saw the New Wavers as lacking forebearers or descendants. That all changed when Richard Neupert published A History of the New Wave in 2002, the first comprehensive overview in English, and now, in this expanded second edition, surely the standard work on the subject.

So accustomed are we to the familiar accounts of the New Wave’s rise and fall (or rather, its slow absorption into the French filmmaking establishment) that Neupert’s drastic and necessary reframing of the story consistently surprises and rebukes our sense of the movement’s contours.

Instead of starting with The 400 Blows and Breathless, Neupert tracks back to the early 1950s, when the harbingers of the New Wave were laying the foundations for a filmic revolution. From Jean-Pierre Melville came the notion of deifying pulp material; from Agnès Varda, the prototype of self-financed poetic filmmaking; from Roger Vadim, unbridled sexuality and, from Alexandre Astruc, the authorial notion of caméra-stylo, or using the camera as a pen. Other French directors, from Jean Renoir and Robert Bresson to Alain Resnais and Louis Malle, were similarly venerated, belying the notion that inspiration for the New Wave came solely from within the Hollywood studio system.

The Cahiers graduates are thus situated within a wider, richer portrait of French history and culture that contextualizes their films much more sharply. This enables Neupert to examine certain less well-known works such as Truffaut’s short Les Mistons or Godard’s immediately banned political provocation, Le Petit Soldat. He delineates the personalities and roles of the major directors: Chabrol the canny financier of his friends’ work; Truffaut the ringleader and Godard the bad boy. The revised edition includes a new chapter devoted to Left Bank filmmakers like Resnais, and a new afterword, which only makes this a more essential acquisition for the hungry Francophile film fan.

Review written by John Patterson.