BY DESA PHILADELPHIA

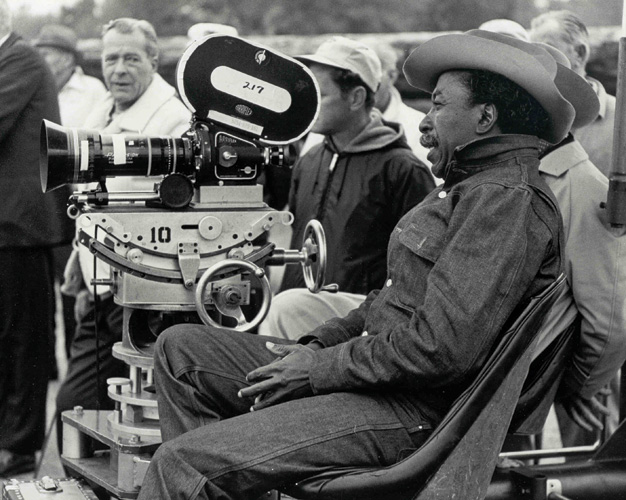

IN THE DIRECTORS CHAIR: Parks not only directed The Learning Tree, he wrote,

IN THE DIRECTORS CHAIR: Parks not only directed The Learning Tree, he wrote,

produced and scored the film.(© Gordon Parks Collection/Pittsburgh State University)John Singleton was only 3 years old when he went to see Shaft with his father in 1971. "My father used to always say, and he looked a lot like Richard Roundtree too, that someone saw him walking down the street and made that movie," laughs Singleton. Singleton's father wasn't unique. The movie attracted large crowds across the country. Black men saw themselves in Shaft, they wanted to be him or be like him. Women of all races thought he was sexy. Even white men dug him; Shaft was the kind of brother they knew they could be friends with. The result was a crossover hit still popular today, and for director Gordon Parks, a legacy as the creator of one of the most culturally important films of the last thirty-five years.

When Parks died last March at 93 and his accomplishments were laid out in scores of biographies, it was clear that he had enduring influence as a filmmaker, a remarkable achievement since he made only five films, and none were nominated for a major award. He also started his movie career after being a successful photographer, writer and composer, at 55, an age when many people are thinking of retirement. But when Parks signed a contract to make a Hollywood film in the spring of 1968, he became the first black man to do so. To the people he inspired most, the young black filmmakers who came to Hollywood following in his footsteps–directors like Michael Schultz and Parks' own son Gordon Jr. in the '70s; Spike Lee, Robert Townsend and the Wayans brothers in the late '80s; and John Singleton, Carl Franklin and Tim Story today–Parks' movies are almost irrelevant to his legacy. What matters is that he did it. The minute he signed that contract, they finally had a role model within the studio system. "I didn't know any other African Americans I could point to when I was at a very young age, saying I wanted to be a filmmaker," Singleton says. And Spike Lee, who lists Shaft and Leadbelly as his favorite Parks films, argues it didn't even matter whether he had seen those films. "Just the fact of who he was, what he did, that was the inspiration I needed," says Lee. "You get inspiration where it comes from. It doesn't have to be because I'm looking at his films. The odds that he got these films made under, when there were no black directors, is enough."

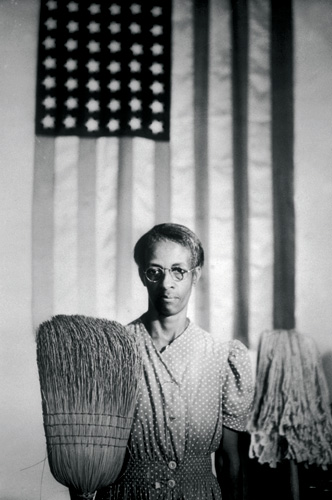

Parks' obituaries also attest to the fact that he was first and foremost a photographer. His contribution to that field is wide in scope and deep in meaning. The youngest of 16 children, his mother told him "what a white boy can do, you can too–and no excuses." Shortly after his mother's death, when he was 15, Parks found himself homeless and on his own. What drove him in those early days, he later wrote, "more than talent or anything else, was my need to be somebody; to save myself from early defeat." Inspired by the work of Dorothea Lange and the other photographers of the Farm Security Administration who documented the plight of the poor during the Depression, Parks bought a camera in a pawnshop for $7.50 and taught himself the craft. "It was to become my weapon against poverty and racism," he said in his autobiography. He got his first big break working at the FSA on a fellowship from Sears Roebuck. He took "American Gothic," his famous portrait of Ella Watson, the charwoman he posed in front of an American flag, mop and broom in hand, on his first day at the agency. It was his response to the rampant racism he found in Washington D.C.

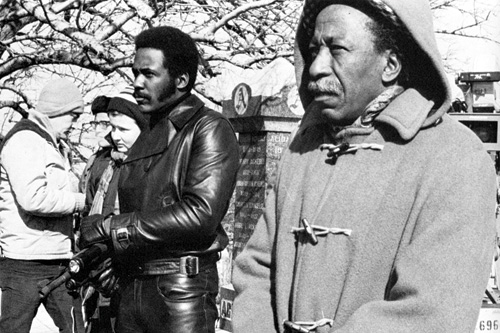

ROLE MODEL: Richard Roundtree and Parks on the set of Shaft.

ROLE MODEL: Richard Roundtree and Parks on the set of Shaft.

(© Warner Bros.)In 1948, he landed a freelance assignment for Life, doing what no one else on the staff had been able to do–take pictures of a Harlem gang. Later, as the first black staff photographer at Life, the most widely circulated photography magazine of its time, he focused on shooting black America, taking his readers through doors the magazine had either ignored or been denied access. He profiled gangsters, Black Panthers, the Nation of Islam, black celebrities. At that time, in segregated America, white people had no idea how black Americans lived and Parks made a career out of exposing this new world. One of his photo essays was poignantly titled "How It Feels To Be Black."

In 20 years at Life, Parks completed more than 300 assignments. He shot high fashion in Paris and the celebrities of the day such as Laurence Olivier, Helen Hayes and Henry Fonda. He played paparazzo as the first photographer to shoot Ingrid Bergman and Roberto Rossellini in the midst of their scandalous love affair. He was also a muckraking documentarian, his photographs of Flavio da Silva, a sickly young boy living in a favela in Rio de Janeiro, and the Fontanelles, a poor family struggling in a Harlem tenement, exposed the collateral damage of discrimination. "His work at Life attracted attention in my house, as a black man who was doing extraordinary work in the world at-large," says director LeVar Burton. Parks' photo features were renowned "to the point where they were being celebrated in the popular culture, by white culture. And that was rare when I was growing up."

Black parents used Parks, and his work, as examples for their children. "My parents would show me the articles and photo essays that were shot by Gordon Parks, so I knew about him much before The Learning Tree and Shaft," says Lee. Director Tim Story's (Fantastic Four) parents kept a stack of magazines that featured Parks' photography. Story says he related to the photography and to Shaft before he knew who Parks was, so for him, as for many, the art came before the biography. "The only thing I can really pull from [Parks], throw into my work, is the art, the photographs, the films. If I were doing a project that dealt with the history of what he was going through, then I could put that in my work, but the only thing I can get something from is the art. Everything else is more about history."

Parks started out in the days before the Civil Rights Act, during the struggle for equality, when there were few black professionals of any occupation, when role models were people who were simply able to build lives on their own terms. By those standards, Parks' success seems miraculous.

Parks brought his bona fide celebrity to Hollywood in 1968. He worked among the poor, but had famous friends–Langston Hughes, Frank Sinatra, Gloria Vanderbilt, Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X–and was a fixture on the society pages. "He was a New York sophisticate but with the touch of the common man," says Frank Yablans, the former head of Paramount Pictures, who socialized with Parks in New York and would later hire him to direct Leadbelly, the biopic of blues singer Huddie Ledbetter. "Here was a black man who presented the kind of credentials and track record the establishment could not ignore or deny," says Burton. "He was a Renaissance man, he did many things and he did many things well," adds Lee.

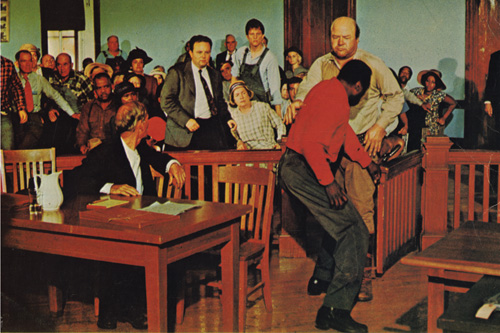

A scene from The Learning Tree (1969). (© Warner Bros.)

A scene from The Learning Tree (1969). (© Warner Bros.) Gordon Parks at the feet of his father while filming. (© Warner Bros.)

Gordon Parks at the feet of his father while filming. (© Warner Bros.) Richard Roundtree shoots back in Shaft's Big Score! (1972). (© Warner Bros.)

Richard Roundtree shoots back in Shaft's Big Score! (1972). (© Warner Bros.)Parks came to Hollywood for two reasons, the first was that he wanted to challenge himself, and making a film had been a goal of his for some time. He had already made a short documentary about Flavio da Silva, the subject of his earlier photo essay. After he published his autobiographical novel The Learning Tree in 1965, about a 15-year-old boy who lived in a Kansas town with fragile race relations, he spent two luckless years trying to attract backing to turn the book into a film with himself as director. One producer suggested making all the characters white. Another thought the solution was getting Gloria Swanson to play Parks' mother.

Parks' second reason for coming west was to break through the color barrier that still existed in Hollywood. Melvin Van Peebles recalls walking down the Champs-Elysées in Paris in 1967, shortly before his first independent feature, Story of a Three Day Pass, stunned the San Francisco Film Festival, when he ran into Parks, "my first black living legend," says Van Peebles. "He talked about the film, the one that he wanted to do. And said he had not been able to crack the white barrier in Hollywood as a director. And I told him not to worry that I was going to let him in."

Then in 1968, actor-director John Cassavetes read The Learning Tree and became determined to help. "There are two things that compelled Cassavetes," wrote Parks in his memoir To Smile in Autumn. "He loved The Learning Tree and he wanted to see that barrier against blacks in Hollywood come down." Cassavetes got Parks an interview at Warner Bros.

"Having been around the media for a number of years, he knew that motion pictures would give him some attention," says filmmaker and historian Melvin Donalson, author of Black Directors in Hollywood. "He used his notoriety, in the best sense of the word, and his fame to make that transition." Blacks had made and distributed independent movies in the early days of filmmaking, led by the prolific Oscar Micheaux, the first black man to write, produce and direct a silent film (The Homesteader, 1918) and a talkie (The Exile, 1931). But no black man had ever directed a studio movie. In the late 1940s, studios began to insert small scenes with black actors into big releases, a ploy that attracted black audiences to those movies, undermining Micheaux and his peers.

In the years immediately before Parks, the only blacks in Hollywood with any influence were the few actors who had attained leading-man status, like Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte (black actresses were not in the picture at all). There were no black studio executives, or even black crew. Hiring blacks, "just wasn't done in those days," says Kenneth Hyman, the head of Warner Bros. Seven Arts, whom Cassavetes had encouraged to back The Learning Tree. Hyman, of course, knew of Parks when the photographer walked into his office, and says he was "impressed by him." Parks' celebrity, and the fact that the movie he was going to make was inspired by his extraordinary life, appealed to Hyman who had more or less decided he wanted to work with Parks before the meeting. "He was a distinguished photographer, a distinguished man. There was no denying he knew about lenses and lighting and photographing people," says Hyman.

Parks also had a story that could appeal to both black and white audiences. "It wasn't a story that had a political edge. It showed racism but it did so in a way that it pointed the finger not only at the white characters but there were black characters that had some flaws," says Donalson. At Hyman's suggestion, Parks didn't only direct The Learning Tree, he also agreed to write, produce and score the film. At Parks' urging, Hyman hired nine black crewmembers. Once he had gotten inside, Parks immediately brought others with him. "Gordon was a master of the system," says Warrington Hudlin, producer and host of the documentary Unstoppable: A Conversation with Melvin Van Peebles, Gordon Parks & Ossie Davis. "He figured out how to be right inside and make it work."

Gordon Parks was adept at filmmaking, but the people who admire his movies don't marvel at his technique. Parks visual style was evident in the way he composed frames like photographs, giving his films a gritty, journalistic feel. "At the time in my life when he influenced me the most it wasn't about studying how he did this shot, it was about the emotion of the moment," says Story. "It's more about what made him so cool or what makes me smile when I see that scene." Parks' films were technically at least as accomplished as many then being shown. "In terms of moving black film forward, they looked as great as the other stuff that was in the theaters at that time, that's almost as important as the stories that were being told," says director Gina Prince-Blythewood (Love and Basketball), "because we had to prove we had the talent to make the same kinds of films that the white filmmakers were making, that they didn't have to be second-class films." The Learning Tree opened to mixed reviews, but it did well enough to launch Parks' second career as a director. For black artists that meant Hollywood was open for business. Within a year, Van Peebles would make Watermelon Man for Columbia and Ossie Davis would direct Cotton Comes to Harlem for United Artists.

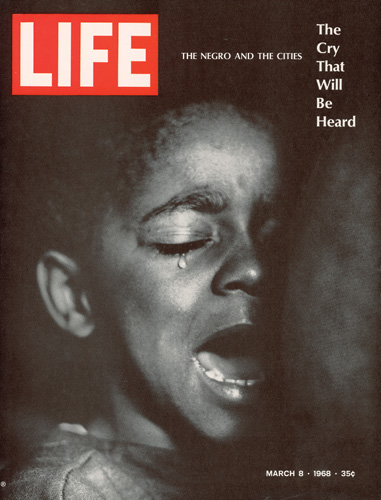

THE BIG PICTURE: Parks' famous shot of a cleaning woman, "American Gothic." A Life magazine cover from 1968 about inner city blacks.

A Life magazine cover from 1968 about inner city blacks.

(© Gordon Parks/Hulton Archive/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)In 1971, MGM hired Parks to direct Shaft, his most influential film. John Shaft, "the black private dick that's a sex machine to all the chicks," as Isaac Hayes' Oscar-winning theme song described him, solves a kidnapping by using connections within Harlem's gangs and the NYPD, moving effortlessly between the two worlds. Parks didn't think much of the script by J.D. Black when he got it, but after making The Learning Tree as a lyrical, picturesque morality tale, Parks wanted a movie that would prove he could be a commercial director. Also, Cotton Comes to Harlem and Van Peebles' 1971 independent film Sweet Sweetback's Baadassss Song had young blacks lining up at the cinemas and Parks wanted to be part of that. Parks also wanted to be an inside man, a real studio player, and he knew a moneymaker could get him there. In his autobiography Voices in the Mirror, Parks advised that black filmmakers who want success have to "broaden their horizons and prepare themselves for any worthy project that means survival."

Shaft was not as much "a film by Gordon Parks" as The Learning Tree had been. Ernest Tidyman created the character, Black wrote the screenplay and Joel Freeman produced it. Hayes' score is as famous as the movie itself. But Parks is in the details. The HBO documentary Half Past Autumn, which was produced in conjunction with a retrospective of Parks' photography that toured the country between 1997 and 2001, includes a video clip of Parks working with Hayes on the music for Shaft. Parks is laying out the pace that the beats should keep as the music accompanies Shaft across Times Square in the movie's opening sequence. Hayes, on the piano, and his guitarist start playing the familiar riff; as Parks' vision comes alive, you can see how he made the scene work.

Parks also insisted that the movie be shot on location in New York, so that the street scenes would be authentic. A day before shooting was to begin, the studio tried to relocate the movie to a soundstage in Los Angeles, a decision Parks successfully resisted. It was Parks who decided that the first black man to bring all his pride, machismo and mastery to the screen would be Richard Roundtree, who was dark-skinned, ruggedly good-looking and, most controversial at the time, mustachioed–just like Parks. "I really pay attention to what people do and what happened before and after, and Shaft changed everything," says Lee. "It was such a visionary thing to see this black detective kicking ass. An African American directed this film, that was huge. Would a white director thought of giving a chance to Isaac Hayes to do the score? Those are insights he brought as an African American director to the subject matter." Shaft also capitalized on the political climate of the day. "If you look at the times and what was going on in terms of the early years of the black power movement, there was a sense of a new generation of younger blacks who were moving away from the Civil Rights era," says film historian Donalson. "Sidney Poitier had been the dominant male figure from 1950 to 1967, so when Parks takes on Shaft he is really speaking to that newer black generation."

THE BIG PICTURE: Roger E. Mosley as Leadbelly. (© AMPAS)

THE BIG PICTURE: Roger E. Mosley as Leadbelly. (© AMPAS)Parks shot Shaft for $1.2 million; it took in more than $18 million at the box office, mostly from young blacks and their white friends. His use of contemporary music and authentic locations were copied ad nauseam in the blaxploitation films of the early '70s which provided a windfall for cash-strapped studios but eventually degenerated into trashy fare, populated by bad actors playing stereotypes. But Parks' vision wouldn't be completely lost. Decades later, directors like Singleton, who remade Shaft in 2000, with Samuel L. Jackson in the lead role as John Shaft's nephew, and Quentin Tarantino, who did his take on blaxploitation films with 1997's Jackie Brown, would help keep the genre alive. In 2000, the Library of Congress gave Shaft its cultural seal of approval by selecting it for preservation based on its historical importance. (The Learning Tree was one of the first 25 films to receive the honor, in 1998).

Parks made three films after Shaft, including the sequel, Shaft's Big Score! (1972), and The Super Cops (1974). His final feature film, in 1976, was Leadbelly, which Roger Ebert called "one of the best biographies of a musician I've ever seen." By then, the industry was at a turning point. A year before, Jaws had become the world's first blockbuster and a new form of moviemaking was born. The following year Star Wars would solidify the trend. "Those are the films that told the studios they didn't have to make films for any niche because everybody in the world is going to go," says Lee. "Black folks were going to Jaws, to Star Wars, black folks were definitely going to see The Exorcist."

Leadbelly also got caught up in a power struggle at Paramount. Before the movie could be released, the studio fired Frank Yablans, the exec who had hired Parks for the film, replacing him with Barry Diller. "There was no way I could protect it," says Yablans. The film was well-received by critics and took the top prize at the Dallas Film Festival, but lackluster marketing and limited release from Paramount meant few people saw it. Parks believed Diller didn't want the movie Yablans describes as a "favorite property" to be a hit. Parks was furious with Diller. "The unpleasant situation that developed between Paramount and myself," as he described it, so soured him on Hollywood that he left, returning to New York.

"What Gordon Parks found and what Melvin Van Peebles found in trying to deal with Hollywood," says Michael Schultz, "is that there were just certain things that the people who were financing the movies, and the people who were distributing them did not want to get behind because they had certain images of who we were as black people."

Parks had enjoyed the Hollywood lifestyle. He lived in Beverly Hills, drove a Rolls Royce and socialized at all the best places. What he didn't like was the way business was done, the way someone could put their sweat and tears into a movie and not have it be given the best opportunity to succeed. He hated the way only certain directors were hired for certain kinds of projects. "I could imagine, given his enormous breadth of talent, that operating in a business that enjoys pigeonholing was truly difficult for him," says LeVar Burton.

In the late '70s and early '80s, in a social climate that had become less political, the most prominent black films were vehicles for pure entertainment. Hollywood discovered that a black co-star in a buddy movie was an easy way to produce a crossover hit (Silver Streak, 48 Hours). Schultz, the major black director of the time, directed the drama Cooley High (1975) and put out a string of comedies, several starring Richard Pryor (Car Wash, Greased Lightning).

"I think what I was able to do was come in at a time when there was social unrest in the streets," explains Schultz, "and the studios were willing to kind of open the doors to women and minorities in a way that they weren't when Gordon and Melvin were coming up. They were looking for black faces they could put at the door and say 'ok, see, we're doing it. We're ok.'"

ARTIST AT WORK: Parks in a familiar position.

ARTIST AT WORK: Parks in a familiar position.

(© Hulton Archive/Getty Images)Spike Lee, who came on the scene in the mid-'80s with a new kind of black storytelling focused on the complexities of race in a changing, integrated America, sees himself as a successor to Parks. Lee describes their connection as "a continuation. From Oscar Micheaux, Melvin Van Peebles, Ossie Davis, Michael Schultz, to myself and Robert Townsend, who brought about the so-called new wave, then John Singleton came up behind that and now you have newer cats. So it's a lineage."

Schultz agrees: "Without Gordon I don't think there would have been a Melvin and without Melvin there wouldn't have been a Michael Schultz and without Michael Schultz there wouldn't have been a Spike Lee."

"I think you'd have to identify Parks as a pioneering filmmaker in the most important sense of the word pioneer," says Donalson. "He was able to enter into Hollywood when you really did not have a black presence behind the camera. What he does is he becomes a complete filmmaker with his first film. He opened that door." Moreover, Parks opened it wide enough so that others could come through. Parks came from the generation of African American professionals who were acutely aware that all their achievements (and failures) would be judged as milestones for the entire race. "There was an urgency to progress the black community," adds Donalson. "They knew they were doing something that not only spoke for themselves but carried the African American communities along with them." In his autobiography Voices in the Mirror, Parks writes about how the accomplishment was bigger than one movie: "Extremely important to me were the number of blacks used in the crew. The number had doubled since The Learning Tree. Slowly it seemed the doors to blacks working behind the camera were opening up."

Directors like F. Gary Gray (The Italian Job, Be Cool), Antoine Fuqua (Training Day, King Arthur) and Story (Fantastic Four) are living Parks' dream of being able to direct any type of project, regardless of the genre or the color of the cast. "There are people I call 'the immortals,' and they are people who made such a difference and left so many tangible and intangible things behind that they never die," says Hudlin. "Gordon Parks was the first black director to have a Hollywood contract, but his lasting legacy is that we cannot accept the limitations imposed by society. He worked at a time when it was repressive, yet he went to the very top. His illustration, by example, is his legacy."