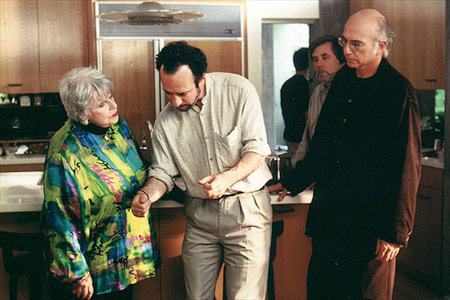

Bob Weide, associate director Dale Stern and Larry David on the set of Curb Your Enthusiasm

Is this any way to run a comedy series? If the name is Curb Your Enthusiasm the answer is: absolutely.

This HBO hit has brought the concept of working without a script into the TV mainstream, transforming its executive producer and star Larry David from the man behind the genius of Seinfeld to the guy who is the butt of every self-inflicted joke on camera in Curb. Shot cinema verité-style, the show uses only an outline, with dialogue improvised and predictability sent packing.

If that sounds like a recipe for disaster from a director's perspective, well, it probably should be. That it isn't is a tribute to the improvisational abilities of Curb directors Bob Weide (who is also the series' co-executive producer), Larry Charles, Bryan Gordon, Seinfeld veteran Andy Ackerman, and David Steinberg, a longtime vet of the scripted television comedy world who has been forced to adapt to the situation comedy equivalent of guerrilla filmmaking.

"Compared to what I'm used to doing, working on Curb is free-flowing and spontaneous," Steinberg says.

"Most people think that you just go out and wing it. But that's never the case. The idea is to capture the feeling of spontaneity without necessarily actually being fully spontaneous, if that makes any sense. You want it simply to sound more real than a scripted show. But there is a formula and a rhythm, too."

Steinberg sees the style of Curb Your Enthusiasm as "a new form where the dialogue is secondary to the concept. You get the feel of a documentary and the beats of improv."

Rather than a script, the directors on Curb (which is in its fourth season) work from a seven- or eight-page outline that drives the plot forward. There is no set-up/set-up/punch line per se. But with its impromptu nature, the show can drive a director fairly batty unless he or she is prepared to go with the flow of a gig that is structured only in the loosest sense.

Bryan Gordon understands. He earned his DGA Award this year for a Curb episode entitled "Special Section" whose "A" story found Larry David (in the role of Larry David) failing to attend his mother's funeral because his father didn't want to call and trouble him. Martin Scorsese, Richard Lewis and Shelley Berman were among the guest stars.

Gordon — who has directed scripted episodes of both comedy (Sports Night, The Wonder Years, Andy Richter Controls the Universe) and drama (Boston Public, The West Wing) — refers to working on Curb Your Enthusiasm as "a high-wire act" during which "all preconceived notions of my job go out the window."

Director Bob Weide (center) preps actors Mina Kolb and Larry David for a scene on the set of Curb Your Enthusiasm

"As a director, when you do scripted shows, you have a sense of where everything is headed," Gordon says. "With Curb, you need to be able to go in an entirely different direction at the drop of a hat. Every scene, you're being tested in terms of getting the information across that you've got in the outline and maybe even trying to incorporate something new while still getting your shots in. It results in a really alive sense that the audience is drawn to.

"I'm not going to say that the traditional sitcom is dead. But the freshness of the Curb format makes you realize that maybe scripted comedy seems a little bit tired by comparison. I mean, I get people all the time who come up to me and ask, 'Is that Larry's real wife and agent?' or 'Is Larry really like that?' I think that's a tribute to the way Larry allows himself to be so unsympathetic."

Adds Larry Charles, a Seinfeld and Mad About You writer/producer as well as a Curb director: "After doing a show like Curb Your Enthusiasm, a scripted three-camera or four-camera sitcom is like a silent movie. It almost seems by comparison like a very moribund form. It feels very contrived and unnatural, almost like one of those stage shows from the turn of the 19th century where the villain came out and twirled his mustache. On Curb, we're able to achieve a level of verisimilitude, of reality, that's really invigorating for a director."

Verisimilitude — now there's a word you don't hear TV directors using every day. But it's one that is also used by chief Curb director Weide to describe a show that isn't directed so much as controlled — with the camera cast as something of an appendage following David and his "real" life. It makes perfect sense that Weide has never directed a conventional TV comedy. His background prior to Curb Your Enthusiasm was as a writer, producer and director of documentaries about the Marx Brothers, W.C. Fields (an Emmy winner), Lenny Bruce (which was nominated for an Oscar and won an Emmy) and Mort Sahl. He knew Larry David long before he became a name on Seinfeld, clear back to his days as a struggling stand-up and then as a cast regular in the early 1980s on the ABC later night comedy-variety series Fridays.

Director Bryan Gordon with his directing team: Associate Director Dale Stern, Stage Manager Jonathan Harris, Director Bryan Gordon and Associate Director Tim Gibbons.

Curb Your Enthusiasm emerged out of what was originally a one-shot deal with HBO to make something of a faux documentary based on David's return to the stand-up world after leaving Seinfeld in the late 1990s. HBO was interested in doing a comedy special about that return to comedy clubs. It led to the October 1999 quasi-documentary Larry David: Curb Your Enthusiasm (directed by Weide) that was a blend of the actual with the ersatz. It applied the rules of documentary filmmaking to an odd hybrid or comedy and pseudo realism.

That would evolve into the series — TV's first fully improvised sitcom — beginning in 2000. The idea from the start, according to Weide, is to "plant little comedy bombs" that detonate throughout the half-hour. "The structure has always been different from any situation comedy that's ever been done," he says. "One thing sets off a chain reaction of events: Event A leads to Event B and collides with Event C, creating Event D."

Two handheld cameras are used. "With an unscripted show, that's a necessity," Weide believes. "Because you never know what may happen, you have to be able to catch the action as well as any important reaction as you may not get a second chance. So much of the comedy comes from Larry's reaction to the situation that I make certain no matter what else is happening, Larry is always covered. We shoot Digi-Beta, but the edited master is run through a process to make it look like film."

Weide admits that while directing Curb, he generally has to improvise right along with his actors (who, besides David, include Jeff Garlin and Cheryl Hines).

"It's really a lot like the CIA," Weide quips. "My standard joke is that actors are given information strictly on a need-to-know basis. They're given whatever back story they need and whatever information their character actually has. They're basically told how they fit into a particular scene. What they don't know is the overall story arc or any scene they don't happen to be in. So they can't really prepare the way actors normally would. When they're hearing news on camera out of another character's mouth, they're hearing it for the first time. So the reaction tends to be very spontaneous."

Very rudimentary storyboarding is done, Weide notes, "but we always wind up throwing it out, anyway. The first couple of takes is a bit like staging a play. It's basically about getting the action on its feet. We tell the camera guys that for the first take or two in particular, it's important to have the camera on Larry to get his reaction. The other camera is the basic master of all the action and making sure all of the people are in the shot."

On a scripted show, Weide says, "The name of the game is continuity and consistency. You do the same thing the same way each time. So the camera operators know you'll deliver this line, set down this glass, walk to that window. You say this line and walk over there and that camera will follow you. But on Curb, the action can be wildly different each time. Body positions are all over the place. The primary direction we give our DP and camera crew is simply to follow that action, wherever it may lead them.

"Occasionally I'll give a continuity note. And we definitely give the actors notes. But generally I want my performers to feel comfortable enough to try different things. If you get enough coverage, you can cover for most stuff. We've shot some scenes where Larry decided to sit for the first four takes and then stand for the next two. But rarely is it that drastic. As a director, you're forced to become very adept at thinking on your feet."

It all sounds pretty darn organized and reasonable. But Curb associate director Dale Stern — who worked in the scripted comedy world on Evening Shade — stresses that trying to direct the HBO show presents a unique set of challenges and obstacles.

"On a scripted show, you have, well, a script," Stern begins. "It's all right there in black and white: where the actors are standing, what the extras need, what your plan is for the day.

"By contrast, an unscripted show like Curb is simply professional guesswork. We know where we're going. We know who's going to be there. We just don't know how we'll be traveling. Let's say we're doing a scene in Larry's house. We have no real clue what that scene will be. The key to success in this game is flexibility. You'll be setting up for two hours in one area when you'll quickly be redirected to set up in another area. You'll start to shoot a scene and realize that the geography doesn't work and that it's better in another room. Sometimes, you just need to turn your entire crew on a dime. It helps a lot to have a good attitude."

Being a little bit insane doesn't hurt, either, Stern admits.

"Believe me when I say that if you can do this show, you can do anything," he says. "It's so completely different from experience on any traditional sitcom. It's not just one or two levels higher. It's so many levels of difficulty and challenge above those that I can't even calculate it."

As an example, Stern points to directing and shooting a simple conversation.

"On a traditional sitcom, you do one side at a time," Stern says. "Here, we have to shoot both sides. Depending on the geography of a room, that's a challenge in itself. You never know who's going to be talking. And if you're shooting a scene where somebody's talking about buying a horse and moving to Kansas, they may talk about the horse in one part and moving in another. The chronological order of the conversation varies with each take. That can just drive you nuts.

"That's not to mention that people can appear and reappear in scenes differently each take. We may use five or six seconds of each take even though we'll shoot the whole scene in its entirety. You don't worry about the beautiful visuals, just the content."

The final scene from the final episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm's third season presented perhaps the ultimate logistical challenge from the directing POV. It involved 26 principal cast members uttering profane words and phrases, a chaotic scene of swearing as a spoof on a character's grappling with Tourette's syndrome.

"We'd been up all night," Stern recalls, "and we had to get coverage on the 26 cast members as well as hundreds of extras while capturing all sorts of reactions."

Remembers Weide, who directed the episode: "It was hard to figure out how to block and choreograph that scene. But I was actually chuckling while talking to my DP and actors about what to do. We have Larry standing there in triumph, having just come to the aid of this chef with Tourette's, as this chaos of swearing swirls around him. We had everybody shouting for about two minutes, using a series of push-ins and pullouts. As we were doing it, I actually thought, 'My God, there's a real possibility that we're creating a classic moment in TV comedy, like Lucy stuffing chocolates into her mouth.' "

Ackerman, whose directing résumé includes everything from Cheers to Wings to Frasier to Seinfeld, finds Curb to be an extension of the character-driven, minutiae-rich world that David created with Seinfeld.

"Larry is truly one of the funniest people on the planet," Ackerman says. "What he's done with Curb is put together a really talented group of people with a gift for improvisation. As a director, your mandate is just to sit back and enjoy the ride while making sure everybody is on camera at the right points. It's really a gas to be a part of that process. It's like nothing you'll ever again do as a director."

"I'll tell you what this show has taught me," Gordon chimes in. "It's taught me to be a darn good listener. You have to really listen, because things pop up that you tend to take for granted when you're doing a scripted show because you know the lines are there. With Curb, you're pretty much on your own. And for a director, what an exhilarating thing that is."