BY TERRENCE RAFFERTY

Photographed by Scott Council

David O. Russell is dressed, as always, in a black suit with a black vest, black socks, black shoes, black knit tie, black horn-rimmed glasses, and a bright white shirt— but there’s nothing monochromatic about his personality, which is mercurial, or his films, which spark and whirl like pinwheels. A week and a half before the Academy Awards, Russell is camped out at The Greenwich Hotel in New York, the gray city of his birth, where his nervous energy and fast patter fit right in. His mind darts and weaves like a cabby in midday traffic.

Since his first feature, the independent hit Spanking the Monkey (1994), Russell’s films have become steadily more turbulent and complex, ranging from the road movie farce Flirting with Disaster (1996) to the Gulf War fable Three Kings (1999) to the gonzo philosophical comedy I Heart Huckabees (2004), and, in the past four years, to the three movies—all nominated for Best Picture and Best Director Oscars—that have sealed his reputation as one of the most adventurous filmmakers in Hollywood: The Fighter (2010), which earned him his first DGA Awards nomination; Silver Linings Playbook (2012); and American Hustle (2013), also nominated for the DGA Award. In all, those last three films have received 25 Oscar nominations, nearly half of them for the actors, with whom Russell seems to enjoy an unusual rapport.

It’s cold in Tribeca, but New Yorkers don’t mind that sort of thing. When you’re on the move, you make your own heat. And David O. Russell, the man in black, never stops moving.

TERRENCE RAFFERTY: You’ve been tremendously successful in the past few years. Now you’re the subject of the DGA Interview and you’re only 55. Nice going.

DAVID O. RUSSELL: Maybe we should wait. Seriously, I can wait until I’m in my 60s

Q: Let’s not. You’ve just had your second DGA nomination, for American Hustle, so this seems like a good time

A: When [then-DGA president] Taylor Hackford called me up to tell me I’d been nominated the first time, for The Fighter, it was the beginning of a major new chapter in my life. After my first three movies, I’d been in a kind of midlife wilderness for a few years. When I was writing I Heart Huckabees, the wheels were already starting to come off because I was overthinking things. By the time I made The Fighter and came out of that wilderness, I was humbled—I actually cried when I got that call.

Q: When did you know you wanted to be a director? Did you see a lot of movies when you were young?

A: I saw a lot of movies and I also read a lot of books. My father worked in publishing, and his company, Simon & Schuster, had some coffee table books about great movies, which I’d just pore over, looking at the pictures and falling into a world of enchantment. When I saw a movie back then, I’d sort of live in its narrative. I’d walk around all day living in The Music Man or Mary Poppins, wherever I was, in school or wherever. I’ve always had a private, interior narrative world; always a movie in my head.

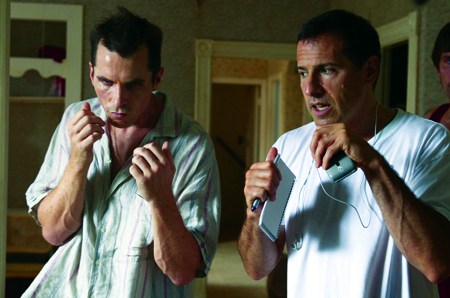

RHYTHM METHOD: (top) Russell’s characters in American Hustle, played by Christian Bale and Amy Adams, bond over the music of Duke Ellington. (bottom) Dustin Hoffman was quick to grasp Russell’s way of working in I Heart Huckabees.

Q: You didn’t go to film school. How did you get started actually making movies?

A: I was working as a community organizer and started using video equipment to document housing conditions in Lewiston, Maine. Later, I was working in the South End of Boston and made a 12-minute documentary about one of the immigrants I’d been talking to. To edit it, I had to sign up for a class at Bunker Hill Community College so I could use a couple of VHS decks. Here’s how I made the cuts. [He pounds the table with one hand, then the other.] They’re not locked machines, you just have to catch that cut. [laughs] I love all that sweat-of-the-brow stuff, because you learn. That video documentary won a cable TV award in Boston. Then I made my first short film, Bingo Inferno (1987), about a bingo parlor in Maine. I had no idea what I was doing. I brought the film to the Sundance Film Festival, and I could see that all the film school kids were just cleaning my clock, so on my next short [Hairway to the Stars, 1989] I decided I was going to really educate myself and do every single thing by myself. Of course, I still had 20 years of learning to go. I feel like it took me 20 years to prepare to make my last three films.

Q: What was it like making the leap to features with Spanking the Monkey?

A: After Hairway to the Stars, I got a grant for a short film from the New York State Council on the Arts. But I didn’t want to make another short, so I spent a couple of fruitless years trying to turn that script into a feature. It was about a fortune cookie writer who wrote very personal things for people in their fortunes—almost like one of the existential detectives in I Heart Huckabees. I wrote it many different ways, but I wasn’t doing it from the feet up, as Irving [Christian Bale] says in American Hustle. I was called for jury duty in Manhattan at a time when I had just broken up with a girl and I was frustrated with my life, and I remembered a summer when my mom had smashed the car and was drinking a lot, and I wove all that into a really angry fantasy. And it came out like that [claps hands]. It just poured out onto a yellow legal pad in the courthouse where I was waiting to get picked for a jury. I was afraid it was too disgusting because it was about, you know, incest, but I left the courthouse with a spring in my step.

Q: It must have occurred to you that it would be kind of a tough sell.

A: Yeah, but I was encouraged by having just seen Gus Van Sant’s Mala Noche and was struck by how personal and unguarded that film was. That movie taught me that the thing you think is too embarrassing or too disgusting, is maybe just a good story. So I started showing the script around and got an agent and some investors. Through my wife, who worked at New Line Cinema, I got some short ends—2:35, not 16 mm, which was very exciting.

Q: Were you always going to direct it?

A: It was my movie to do. I learned a lot about directing from it. There were scenes where I felt I was kicking ass and taking names, because I knew exactly what I wanted, and then there were other things that kind of got the better of me. But, you know, it takes many years to become really good at something, and it was good enough. The fact that the movie was claustrophobic, all in one house made it simple to shoot—in 23 days—and get footage in the can for $80,000. To finish it, I needed another $100,000, which I got from the guy who invented Bugle Boy pants. Pam Martin, who later edited The Fighter, cut it with me on a Steenbeck in my dining room.

Q: Spanking the Monkey made a splash at Sundance, didn’t it?

A: We won the Audience Award, and got a distributor there. Thanks to movies like Van Sant’s, it was a good time for darker films. But Harvey Weinstein told me, ‘You’re going to be hot for about five minutes, and then it’s going away. If you don’t act quickly, the opportunity passes.’ So I wrote Flirting with Disaster very quickly. I wanted to do something more fun.

Q: Of course, some people think of Spanking the Monkey as a comedy.

A: I always called it a feel-bad movie. But there’s always comedy inside the darkness, you know? That’s just how I see things. It’s in my DNA.

Q: In Flirting with Disaster, you wound up working with a lot of very high-profile actors for the first time.

A: I was meeting a lot of my heroes—Alan Alda, Mary Tyler Moore, Lily Tomlin, George Segal. And Ben Stiller, Patricia Arquette, and Téa Leoni all had a lot of experience, too.

Q: Did you know right from the start how you were going to approach directing actors? Did you always have a feel for it?

A: Well, I just knew what I wanted them to do and tried to help them do it. I knew I could get there from the basement, or the front door, or the back door, or through the window—any which way I could communicate to them how I thought the scene should happen. I could just humbly sit with an actor and say: ‘I don’t know, let’s talk about this together. I do know what this should ultimately look and feel like because that’s my job. I’m always open to surprises, but we’ve got to get to this core stuff; that’s the movie.’ One thing I learned making those first two movies was how much dialogue in cinema is about rhythm. The rhythm has to be like in music. And not just the language—the visuals, too, every shot is rhythmic.

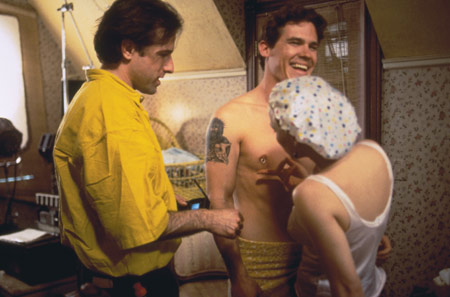

HANDS ON: (top) Russell shows Christian Bale how to throw a punch in The Fighter. (bottom) The director frames a shot with Bradley Cooper and Amy Adams in American Hustle.

Q: So do you like to rehearse a lot?

A: Before I shoot a scene, I go onto the set and kind of act it out to myself. Then when the actors come in we start running it, and running it, and running it so they all get the rhythm of it—the rhythm of the language and the rhythm of the scene’s energy. Then once it’s basically blocked out and the rhythm is right, I want to get the camera going pretty fast. I don’t want there to be a lot of time for people to go over and over how the scene’s going to play, they just have to jump in and give themselves to it.

Q: Are some actors more comfortable with that than others?

A: Dustin Hoffman, in I Heart Huckabees, grabbed onto my rhythm as well as anybody, and Bradley Cooper did in Silver Linings Playbook and American Hustle. Robert De Niro, in Silver Linings, was always saying to me, ‘You have a very specific rhythm, David, and I’d like to get it right.’

Q: When the rhythm is right in your work, the films have a wonderfully spontaneous feel. Do you storyboard much, or do you prefer to rely on the less predictable elements of filmmaking?

A: I always have a shot list, and I always know what I want compositionally. You have to storyboard action stuff, like in Three Kings. I made that picture because I wanted to come out of that dark, intense, somewhat more cynical place I’d been in as an angry younger man—I’d worked through that in the first few films, and I wanted to do something bigger. Something more muscular, about men who weren’t wobbling so much, like the guys in those first two movies. I wanted to shoot some action.

Q: Did you find that difficult?

A: I loved constructing the rhythm of the action in Three Kings. I knew how I wanted to build it, and I did it. That said, I can’t say I have any big desire to do action again.

Q: Was that your main reason for doing it?

A: For me, that movie was a meditation on violence. There are only about five bullet shots in the whole film, and we wanted to make every one of them count, so that’s why we went into the body—which CSI kind of appropriated afterwards. We did that practically, not digitally. We also did some shooting on reversal Ektachrome stock, which freaked out Warner Bros. a little bit; we had to change labs because you couldn’t see the actors’ eyes. We first did a bleach bypass, using a layer of silver nitrate on the film to give it a blown-out quality— which now you can do on your phone, so for anybody under 40 it’s like, ‘who cares?’ But at the time it was a big deal, especially for the studio. Once they went down that rabbit hole, it became Ektachrome, which has very saturated, intense colors, like the color photographs on the front page of USA Today. When you’re doing stuff like that, you have to be very committed. You’re making all these turns and you have to do them in such a decisive way that you take everyone with you.

Q: Let’s take a bit of a turn now. Can you talk about the filmmakers that inspired you most?

A: Frank Capra is a very big influence, It’s a Wonderful Life in particular. I love the populism of his films: the sweeping, almost operatic range of the stories, and the soulfulness. There’s a noir quality, too, which is unflinching, and yet a great amount of heart—though sometimes he overplays that hand. There’s a beautiful innocence at the center of Capra’s work that allows him to see all the bad things in a very powerful way. I especially like the way he creates a sense of community—Martini’s restaurant and bar, Gower’s drugstore, the home, the main street, the Building and Loan versus the bank.

Q: You get that sense of community in The Fighter and Silver Linings Playbook.

A: There’s a scene in Silver Linings where Bradley Cooper goes to pick up Jennifer Lawrence for a date, and all these people are looking out their windows—an old widow, her parents, different neighbors—and you get the feeling of a real neighborhood. Which of course it is, in Upper Darby, outside Philadelphia; everybody on that street knows everybody else. I really like making movies on location, being part of a community, casting people from the community. There’s a sense of excitement.

GOING TO WAR: Russell’s crew follows him through the desert on Three Kings. He wanted to come out of the dark, cynical place of his first three movies and do something bigger and more muscular.

Q: Does the shooting change much when you’re on a location like that?

A: On the day, not that much. There’s always a lot that I have storyboarded, or shot-listed, or that I’ve written into the script. There are certain shots I know I want to do, and some days there are more and some days there are less. I have an affinity for a handful of shots, which I can describe to you right now…

Q: Sure.

A: One is from Capra. There’s a book called American Vision: The Films of Frank Capra, by Ray Carney, which I read many times, and studied its pictures very carefully, 30 years ago. There’s a sequence in a train station in It’s a Wonderful Life, where Jimmy Stewart is picking up his brother who’s coming home from college. Stewart is standing by the train and you’re watching all this emotion fall across his face like weather. Capra stays with it as Stewart slowly starts moving through the crowd and the face gets really big in the frame—people are bumping into him, and there’s all this depth behind him, but you’re lost in the emotional moment with this man. It’s a very long shot, and to me it’s just magnificent: This is what it feels like when the world is swirling around you. I did something like that in Silver Linings , with Bradley outside the movie theater after Jennifer has turned the whole crowd against him. You know, I love formality and composition. I love deep backgrounds and close foregrounds; the intensity of someone being up in the lens, and someone being behind them. I love depth.

Q: So it’s the placement of an individual against a background that interests you?

A: To me, the whole movie is, ‘Who is this person?’ Cinema is looking at people: Every aspect of their hearts, their emotions, their clothing, their closets, their bathrooms, their food, their lovemaking, the way they comb their hair. I want you to become very intimate with them, because these people are the music of the movie. All my movies begin with, ‘Who is this man?’ In Silver Linings, I start on Bradley Cooper’s back. In The Fighter, it’s Christian Bale sitting on a couch speaking directly to the camera.

Q: Did you always plan to start The Fighter that way, or was that something you decided in the editing?

A: On that film, I decided in the editing. The original opening was Mark Wahlberg raking in the street, starting off on a shot of the rake and then Mark’s back coming into the frame, just as it did in Three Kings. That film, you remember, starts on an empty, open frame of the desert. You hear the noise of boots crunching, and into the lower right corner of the frame comes this person who stays there and has a conversation with someone else off-screen. In the scene in The Fighter, you also have the open point-of-view, the street, and then the rake and then here comes Mark into the lower right corner of the frame as he addresses someone off-screen, over his shoulder, and then his brother’s fist comes into the frame. It’s a similar sort of narrative painting. That’s all designed, of course. I think in pictures, I love thinking cinematically.

Q: For sequences like that, you storyboard and don’t really change much in the shooting?

A: We make it look easy and effortless, but from your line of questions I can gather that people think it’s an accident; that I make it all up on the day.

Q: No, I don’t think that at all, I’m just asking about how you get that effect of spontaneity—the kind of lifelike mess and chaos you capture so vividly.

A: That whole chaos thing? I don’t know what the hell people are talking about. I’d love for them to tell me what they’re talking about. It’s not chaos, I can tell you that: it’s storytelling

TAKE FIVE: (top) Russell, with Josh Brolin and Patricia Arquette on Flirting with Disaster, and (bottom) Bradley Cooper on Silver Linings Playbook, will go through “the basement, the front door, or the window” to help his actors nail a performance.

Q: I can assure you I don’t think you’re just getting your effects by the seat of your pants.

A: Let’s talk about this so-called chaos. Go back to The Fighter —there’s [a scene with] Christian Bale on the couch. Mark comes in, sits down, and doesn’t say anything—it’s by design, he wouldn’t say a word because he’s the quiet brother; there’s a contrast. You go to the Super 8 footage of the mother and the family—that gives you an evocative sense of a mother teaching boxing, a big brother and a little brother; it’s all very specific. And then you’ve got the rake, Mark [moving] in, and the fist coming into the frame—which I just love as a composition—and Mark ignores it like it’s a mosquito. And they start acting out a fight, playacting, and you’re feeling propelled into a real situation. So sue me, I’m creating life.

Q: I think that’s something you feel strongly in the film.

A: I’m opening with an overture that goes on for five minutes. We see that Bale’s character, Dicky, is playing to an HBO camera crew, who are making a documentary about him. And then the camera zips down the street, which is a shot that, when I saw the location, in Lowell [Mass.], I thought ‘look at the telescopic effect of these symmetrical houses, all very close together on this narrow street. If you zipped down this street fast on a golf cart, and went seamlessly from the brothers talking to the HBO crew, you’d get that effect.’ So I told the Steadicam guy, ‘Punch it! That’s not fast enough, you’ve got to floor it—take the governor off the gas if you have to!’ We re-worked the engine to make it go faster and achieved that telescoping effect, a little vertiginous. I picked that street and that intersection for a reason. Everything I’m describing to you is not chaotic or improvised; it was very deliberately selected.

Q: You’re using the location to say something about the life of the characters.

A: I chose that location because I love the sense of depth. It’s a massive wide shot that shows you four different streets, all those low buildings, and guys in the middle of it paving a street. And you turn left down this teeny little narrow street and you can telescope, getting a sense of these brothers becoming very tiny figures in this community. Which, in a way they are—small figures in the fabric of this hardscrabble mill town, just woven into the fabric of the streets and the houses. So in one shot, you get all that. Then they walk down the main street, buy a Lotto ticket, and you can see people scratching their tickets. This is all a choreographed Steadicam shot that we later chopped up, but it still achieves that left-to-right motion. You’re moving, going through a world, and you’re seeing all these very carefully chosen people in carefully chosen locations.

Q: How did you apply that aesthetic to the opening scene of American Hustle?

A: What I’m trying to do is propel you through a very dense experience of life. Maybe it seems too lifelike to people, and that’s what makes it feel chaotic to them. I can go through the openings of all my movies, of Silver Linings Playbook or American Hustle, which are tapestries. In that one, what you see first is this man—again Christian Bale—doing his hair, and you think, ‘My god, who is this and what in the world is he doing?’ It’s not about the hair. It’s about his entire gig, about life and about identity—the fragility of identity and the passion of identity. He’s constructing his identity, and you can see he’s under a lot of pressure, but you don’t know why and you want to find out. We go down the hall with him, and it’s very intense. We did a sound design so that the air is sucked out of the shot once Bradley Cooper bursts in, but until then the intensity is building up—this sort of ambient sound design—with a kind of indecipherable sound of a reel-to-reel tape recorder. Then Amy Adams comes in and they’re looking at each other, fraught with meaning—we don’t know what their story is but we can see they’re deeply connected—and then the door bursts open and all the ambient sound stops, poof! The tension is broken and we’re propelled into this triangle, which is a new kind of intensity. Maybe ‘intense’ is the word rather than ‘chaotic.’

Q: It is intense. What effect are you trying to create for your audience with that?

A: That opening scene in American Hustle is like the parlay scene in Silver Linings, where everyone is arguing over the parlay, and the audience has no idea what a parlay is. But it knows these people are very serious about it. I like scenes like that, in which the audience doesn’t quite know what’s going on, and then the penny drops. It’s like the scene in The Fighter when Mark Wahlberg and Amy Adams sit down with his mother and his sisters.

PAINTING: Russell takes extreme care with the framing and composition of shots like this one from Silver Linings Playbook. “I love formality and composition, deep backgrounds and close foregrounds.”

Q: For a group scene like that one in The Fighter, do you use multiple cameras?

A: It depends. In that scene in The Fighter where everyone is sitting down, there is a particular kind of energy. We did have two cameras, one on one side of the room and one on the other, which was very simple. The parlay scene in Silver Linings had more moving parts—more people, nobody sitting, everybody moving around. For a scene like that, I do what I call ‘interlocking.’ I did a roving master going one way that’s hubbed around De Niro, and a roving master the other way hubbed around his adversary, Paulie Herman. I let most of it play in the wide shot. You get a great sense of realism; the action is unbroken, and Jennifer and Bradley are reacting in real time right next to Bob.

Q: I have to ask you about the soundtracks of your movies, especially the last three films, because they’re so distinctive. Do you always have particular music in mind for specific scenes?

A: Actually, I have a repertoire that I’m lying in wait to use when the moment comes, and you don’t know when that moment’s going to present itself. ‘Jeep’s Blues,’ the Duke Ellington song in American Hustle, was in my secret treasure trove for 30 years. Duke Ellington died in 1974, four years before the story of the movie. I remember it well; I went to one of his last concerts. This is the music these characters love. They say, ‘Who begins a song like that?’ (Somebody might say, ‘who begins a movie like that? With a man combing over his hair?’) Ellington was such a creature of his own invention, a butler’s son who made himself an icon of rhythm and elegance, and both these characters understand that and love that.

Q: So it’s a song finding its moment.

A: And another one did, too, ‘I’ve Got Your Number,’ which I’ve always loved. There’s an art to using certain music. First of all you must love it, and second, it doesn’t matter if a song has become commonplace or clichéd if it hasn’t really been used and embraced the way you’re going to use and embrace it.

Q: That song comes in at a moment when the con artist lovers are riding high and go dancing to celebrate. How did you get the idea to have Jack Jones singing it live?

A: My music supervisor, Sue Jacobs, suggested that, and I didn’t know that he was still active. Which he obviously is. [laughs] And in good voice. So I designed a shot that would start across Park Avenue, where the characters’ offices are, and go into our version of The Pierre Hotel.

Q: Why The Pierre? It’s such a quiet, traditional, Old World sort of hotel.

A: I like to do the square things, because in my book that’s what’s really cool. In the ’80s, when everybody was going to, I don’t know, Area, or other discos, I was going to this little cafe in The Pierre where blue-hairs would go dancing with their companions, and I’d dance with them and thought it was great. I thought it was right for these characters in American Hustle, with their love of life and of each other and of elegance and of old-fashionedness and of squareness—their love of Duke Ellington, at the height of the disco era. That’s why I loved them, and that’s why it’s worth paying attention to these people. To me, they’re not just pathological criminals, but people who have a very specific humanity and love of life. So, going back to the shot, we go across Park Avenue and into The Pierre, and then we look up at the ceiling of the room, across the crowd of dancers, and Christian and Amy are singing now in sync with the song. This all has to be choreographed very precisely; you’ve timed it all out and chosen exactly that stanza to land on. And then you can pan or cut—we could have panned, but we decided to cut—to Jack Jones, perfectly in time. It’s all syncopated, with a smooth left-to-right movement, and you’re right with it. It’s all together, and that’s magical.

Q: Rhythm is everything, right?

A: It is.

Q: And your career seems to be in a good rhythm, now.

A: You know, directing is really hard, and I had a lot to learn. I’ve got to say, seeing interviews at the DGA and watching them online—Mel Brooks or Oliver Stone or Mike Nichols or Warren Beatty—was a great part of my growth as a director. And when I did an interview with Dennis Hopper about his career, that was pretty exciting for me. There’s just so much that goes into directing, into crafting these worlds, which are big worlds. It’s like conducting a symphony. I just feel blessed to be a part of it.