SHOT TO REMEMBER

By Rob Feld

Landing a neat 10 minutes into Lords of Dogtown (2005)—Catherine Hardwicke's homage to the members of the Zephyr Competition Team (the Z-Boys), whose Southern California style and creativity transformed the evolving sport of skateboarding in the 1970s—is a sequence portraying the moment that enabled the Boys' revolution. To accomplish it, Hardwicke harnessed the attention to detail she brought as a production designer, her personal relationships to surf culture and with her Venice Beach neighbors, and a willingness to experiment on-the-fly.

Landing a neat 10 minutes into Lords of Dogtown (2005)—Catherine Hardwicke's homage to the members of the Zephyr Competition Team (the Z-Boys), whose Southern California style and creativity transformed the evolving sport of skateboarding in the 1970s—is a sequence portraying the moment that enabled the Boys' revolution. To accomplish it, Hardwicke harnessed the attention to detail she brought as a production designer, her personal relationships to surf culture and with her Venice Beach neighbors, and a willingness to experiment on-the-fly.

"This was a magical time in the '70s when this burst of creativity came from these kids who were from the wrong side of the tracks," says Hardwicke. "They had shitty, unstable home lives. They weren't good in school and couldn't afford an expensive sport. But anyone could buy a skateboard super cheap. And with Skip Engblom as their father figure, it felt like the family they didn't have."

The sequence starts in the Zephyr surf shop in Santa Monica. Shop proprietor and surfboard shaper Skip Engblom (Heath Ledger) has just purchased newly invented urethane skateboard wheels, and shopboy Sid (Michael Angarano) is sharing them with his friends—Jay Adams (Emile Hirsch), Tony Alva (Victor Rasuk) and Stacy Peralta (John Robinson)—who hang around the shop. The kids ride off to the school yard with the softer, grippier wheels to try them out.

To capture the action, Hardwicke and her director of photography, Elliot Davis, shot a variety of formats, including 35mm and 16mm stock, and a lipstick camera that shot digital frames. They also pushed color and textural elements in the early days of using digital intermediate. They put cameras on poles and skateboards, taught actors to skate and skaters to double, while using the real-life characters on-set to train and individualize the unique styles of each actor's skating.

This is the Zephyr surf shop in Dogtown, and a turning point in skateboard history and in our film. A guy walks in with a brown paper bag that we think is drugs, but it's actually urethane skateboard wheels. Their eyes are popping, in awe of what these wheels could let them do. We used a lot of backlight and a very controlled 1970s palette in the wardrobe. Their hair is very detailed out with extensions or a wig on every actor—but wigs that you could skate or surf with. We recreated the Zephyr shop quite accurately from photographs. We found a furniture store in Long Beach that was very similar to the Zephyr layout, and rebuilt it. All the surfboards there were made by the real Skip Engblom and his crew. Heath also spent a day with him, learning how to shape boards.

I think this was exactly from my storyboards. I wanted a detail where you saw the old hard wheels that have no give to them, bottom center of the frame. They get those wheels off as quick as they can to try the urethane ones. You hear the ball bearings drop. Look at that yellow piece of metal on the left-hand frame; I mean these kids did not have money. A whole bunch of skaters live right down the street from me in Venice. Half of them and their families were around for these events in the '70s, so people would bring me the real boards and say, "You gotta make it like this!" It's such a beloved community that there was this outpouring of authenticity.

This is a Santa Monica junior high school, where the boys really skated back in the day (and still do). I love to have foreground elements like shooting through a fence. It's a barrier for them—no kids allowed, no skating after school—but they deal with all obstacles. I used to be a production designer and the idea that every last detail has to be authentic carried through for me as a director. We did living-wardrobe and hair/makeup tests in Dogtown, not in front of a boring gray seamless. Doing them in a real location gets you excited, gets everybody into the groove with the real music playing.

I remember all the actors were asking how they were supposed to climb over the fence. I just said, "When I say action, just get over that damn fence any way you can." It was kind of chaos, but kind of fabulous. Because the ground sloped down, we could have this great low angle shot at them. Elliot Davis, my DP, insisted we shoot this whole sequence late afternoon. And once we figured out what the look would be, we had to stick to it. Generally, we were crushing the blacks, pushing the highlights, and accentuating the grain subtly so that it felt more like a movie from the '70s.

Skip told me he wanted to be depicted warts and all (basically wasted the whole time), so here he is lecturing his guys with a board in one hand and a bottle of booze in the other. I love that low angle looking up at him—he was their god, he was their father when most of the kids had negative father situations or none at all. We made that wig and false teeth for Heath—all those real details like the beads made him feel like Skip. Heath grew up skating and surfing, and went to Costa Rica for a week just to get back into the surf vibe. He hung out with Skip and really flowed into the character naturally.

This is Adam Alfaro, the stunt double for Tony Alva. I decided to get real actors and teach them to skate, rather than the reverse, so my plan the second I got the job was to get actors quickly so they'd have time to train. The Boys realized with the new wheels they could carve their turns like surfing a wave. My challenge was to make the audience feel like it was really living it. That's why it's shot handheld, Steadicam, motorcycle cam and skating cam. There's no lockdown or dolly shots, and we would use an A-Minima Super-16 camera on a pole when we wanted to get in front of the skaters. We also wanted it to have an edgy, current-day look, so we pushed the highlights and crushed the blacks.

Here we have a lipstick camera mounted on the bottom of the skateboard. I wanted to see the wheels gripping the pavement—and they look incredible, back-lit by the sun. The lipstick camera had a cable running up the double's pants to the battery in his backpack. It captured these 800-line frames that had to be stitched together and interlaced to create a high-resolution image. Recording the grind of these wheels on the asphalt was challenging but it's such a distinctive sound, it really immerses you in it. I remember the sound designer would go out and record all kinds of wild sounds and layer them. Because the real-life skaters were on set, they kept it authentic, kicking my ass if I did anything wrong and kicking the ass of the person playing them if he wasn't skating in their style. Sometimes the real guys, in their 50s, even did their own stunts because they could do them better than the doubles, and made it look effortless.

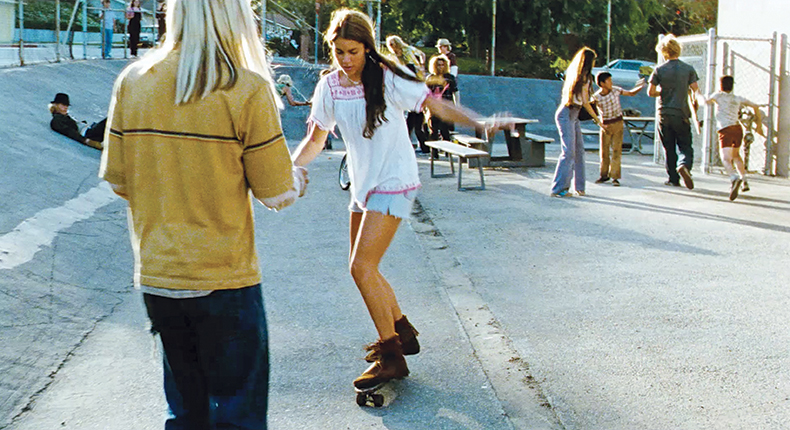

As they're trying out the wheels in the school yard, our three boys notice that they've attracted a bit of a fan club. Jay and Stacy on the left notice Tony's (on the right) sister, Kathy. When I got the script, there weren't many female parts so I asked the guys who had been important to them. Tony Alva said to talk to his sister. Kathy had a great relationship with her brother but had also dated his two best friends. So, I added that character and cast Nikki Reed.

Nikki learned how to skateboard for this shot. Stacy's the first one to make a move on Kathy but you can see Jay is clocking her as well, on the left of frame. Tony (the protective brother) is also watching in the background like, what the hell? If it's possible, I love to build that foreground, middle ground, background where you have other characters observing so the stakes are high at all times. Stacy's a gentleman and he helps Kathy to skate, but she ultimately goes for Jay, the bad boy. In actuality, (Nikki) and Victor fell in love on set and had a two-year relationship, but he was playing her brother. I said, "Listen, if I see that on screen, that's not going to work!"

Here we're in close-up because Stacy and Kathy are on their own little bubble, having that magic moment of connection. Everybody else is out of focus. This scene actually shows one of two completely contrasting looks Elliot and I worked in the digital intermediate for this sequence. Here it has that late afternoon look with backlight, shooting into the sun. It's kind of glowing and beautiful because it's a magical moment for the boys.

Here, Tony bursts their bubble. He does not like anybody hitting on his baby sister. I wanted to shoot this movie like war photography because there are so many explosions in their relationships. So, I wanted the camera to be moving at all times to capture those kinetic moments. They also never sit still. I didn't know how I was going to keep up with them because the way I direct, I'm not at video village. So, I was riding on the back of motorcycles, on jet skis or surfboards, following them. If you look at the boys' wardrobe, nobody was ever clean. As skateboarders, they're always hitting the ground and they wore the same clothes every day, (so) there were no continuity issues.

The boys move on to skate the ditch, where they're just flowing like a river, and we switched the look in the DI—desaturated, which wasn't so trendy at that time. We mostly shot Panaflex 35mm cameras—always an A and a B camera. Elliot is a handheld master on A, and George Billinger was on B—he's a really big guy and was able to mount the camera on a pole and hang it over. But my secret weapon for shooting these skating scenes was Lance Mountain, who was a world-renowned skater in the '80s and skated behind them with an Aaton 16mm camera. He understood the lines the skaters were going to take by watching them shift their weight, so he could smoothly flow after them on his board. It's the reason it looks so immersive.

Each character is finding his powers and creativity. It's an expression of pure bliss and freedom. Stacy, Tony and Jay were always trying to one-up each other, pushing the sport. Our music supervisor, Liza Richardson, drilled down on all the evocative music from that time that you just feel in your bones—here, it's Iggy and the Stooges. Their music was integrated into the style of skating because, for these rebellious, frustrated kids, the pounding of that music helped them. The location was in Imperial Beach and a lot of the graffiti was there, but we added some Venice to it. The skaters found poetry from a drought and empty pools.

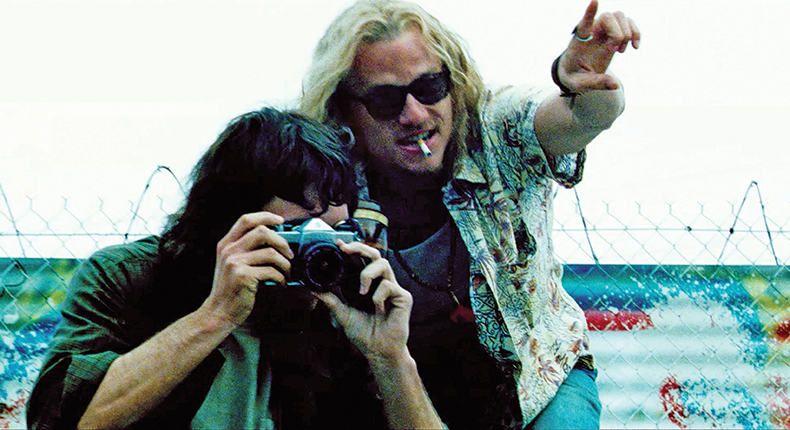

This is the moment when Skip and Stecyk are realizing the magic they've got there—Stecyk was an artist who captured the Z-Boys' attitude and rebellion. He and Stecyk are curating it and turning the boys into something that some of them eventually resented—merchandise and branding. Heath became his character—he just did what Skip would do without thought to any consequences.