By Rob Feld

The Khmer Rouge uprising and takeover of Cambodia was a little spoken about or understood footnote of the Vietnam War when producer David Puttnam gave Roland Joffé a 300-plus-page screenplay for The Killing Fields, adapted from Sydney Schanberg's reporting in The New York Times. To Joffé it was revelatory but he also felt it could be unlike any war movie he had ever seen. "It's about love and male friendship," Joffé wrote to Puttnam. "If the story is made from that point of view, I think it will turn into an unforgettable movie."

The Khmer Rouge uprising and takeover of Cambodia was a little spoken about or understood footnote of the Vietnam War when producer David Puttnam gave Roland Joffé a 300-plus-page screenplay for The Killing Fields, adapted from Sydney Schanberg's reporting in The New York Times. To Joffé it was revelatory but he also felt it could be unlike any war movie he had ever seen. "It's about love and male friendship," Joffé wrote to Puttnam. "If the story is made from that point of view, I think it will turn into an unforgettable movie."

More than a year later, Joffé found himself in Thailand, chronicling the story of journalists Schanberg (Sam Waterston), Dith Pran (Dr. Haing S. Ngor), Al Rockoff (John Malkovich) and Jon Swain (Julian Sands) at the moment the Khmer Rouge invaded Phnom Penh. When he could have been evacuated, Pran opts to stay behind and report with his colleagues.

The invasion sequence formed the heart of the movie for Joffé because it sets up the ultimate separation of Pran and Schanberg, and shows how Pran risked his life to save Schanberg and his fellow journalists. The sequence is chaotic, dangerous, bloody and imbued with the men's confusion at the new state of affairs.

"It wasn't a question of depicting what exactly happened," says Joffé. "We wanted it to feel as real as it possibly could but more importantly, to convey exactly what it felt like to be in it.

"I wanted that whole sequence to be in constant movement," the director adds. "The universe was upending. The camera movement created the feeling of discombobulation. It created in the audience the kind of tension and fear that I wanted."

"They are about to flee but the tunnel is blocked by an APC (armored vehicle), which isn't going to stop," explains Joffé. "This image was just to do with raw power, and it set up the very mobile camera that makes the sequence work. It was on a dolly and track, and it had to traverse the car and look like it almost got run over by the APC, which it nearly was. Luckily, our operator had nerves of steel. For me, this was about creating the panicked feeling of what it's like when you suddenly don't have any control, when once you called all the shots."

"We used a longer lens than one might because we wanted some compression, but the movement had to have a smoothness to it. I didn't want things to look handheld because I didn't want to lose a sense of contained energy. The discipline would have disappeared and it wouldn't have felt as real, like it's going to pop out of the screen. To give it reality, we spent a lot of time with those costumes, with hordes of people dragging them through the sand, driving trucks over them, washing them hundreds of times so they felt like they had been in a conflict."

"The camera lands on this boy as an introduction to the role of children in this story, which is both innocent and brutal. When innocence is perverted, it can become terrifying because it has no boundaries. Terry Forrestal, who did our stunts, had been working with a group of kids to be our young Khmer Rouge. One day, he came in white-faced and said, 'Roland, the thing is, if I asked them to kill you, they would.' Terry removed the taboo against breaking certain rules of a very constrained culture. The unleashed anger from overcontrol just popped out."

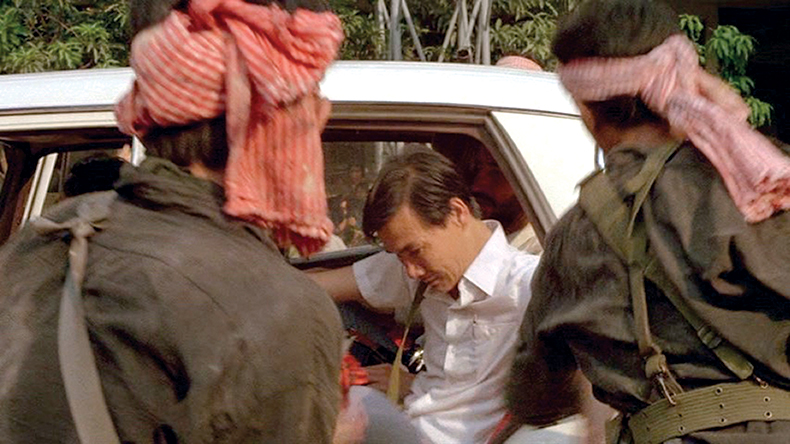

"Now it's a different world, the power is reversed, and they're getting pulled out of their nice Peugeot. Haing Ngor, who was a doctor, not an actor, was seized with genuine panic—the panic of recall. When I'm setting up shots, I imagine myself to be a scuba diver, capable of moving around something and looking at it from different angles. Here I set the car as the central point and built action around it. Then I could design the camera move to spin around it. It looks like chaos, but you create a still center around which things can move."

"We wanted the constant cuts to be slight jolts, and each one should contain an image of violence and misunderstanding. The editing is tied up with the cacophony of voices and sound—people shouting but nobody knows who or for what. Pran is talking but we don't know what he's saying. At this juncture, nobody knows what's happening next. Are they even Khmer Rouge? It all had to have movement and a jagged quality to it, so we messed around with the sound during the mix to give it a higher frequency, to make it jarring without you quite knowing what it was."

"If you look at their faces, they are mentally there in the reality of the moment because we improvised a lot about what would happen when they got caught. We did improvisations in the dark, and they're wonderful actors, so they internalized it all. In fact, they didn't know what was being said here. It's as though there wasn't a script. At that point, the script was kind of irrelevant in its detail. It was only relevant in its thrust. I told Haing he couldn't turn down the role, that Cambodia would never forgive him. I had no right to say that, but directors do things they have no right to do."

"They are moved to these warehouses by the river, which gave [us] images you cannot get anywhere in the west: banana plants, rusted corrugated iron, and the sweat and the heat of the whole thing. Also, this sense that you're in a small space where everything is sharp. It's not a good place to die. It had a beauty and brutality to it. That mixture to me was very, very important. There's also the two energies going on of Sydney and the others—who have to control their confusion and fear, as they realize Pran is keeping them going—and Haing, who suffered from the Khmer Rouge."

"Close-ups are like little beats when you're drumming, and sometimes you want emphatic beats. If they're done well, they destabilize you because they interrupt the rhythm. But at the same time, they punctuate what's going on, which is particularly important in this kind of sequence. Haing told me about his experiences with the Khmer Rouge. I would crawl around on the floor underneath the camera while Haing was working and give him a little running commentary in French. It would all add to the general mayhem but help Haing feel connected to what was going on."

"After all that kinetic rush, I wanted people to suddenly feel the weird stasis of, have they been there five minutes or five hours? And there's something physical and anguished about crouching. We stayed on long lenses to pull up the backgrounds and keep a claustrophobia, even in these wide shots. The light in Thailand has an odd quality because of the humidity; it's a strange diffusion. When we started assembling things, we realized that we didn't want the reds to be too sharp, and that we wanted to get the slightest underwater 'greeny' qualities, to add an element of heat. In Southeast Asia, you are underwater with the humidity being what it is."

"A man puts an apple on his bayonet and makes people take bites, but then suddenly shoots one person in the face. It's the arbitrariness of this moment. It leaves you with the idea, 'I can't prepare myself for anything because I'm not going to know what happens next.' You're torn between hope and despair; each time you try to master your fear, you're given a moment of relief, which means you let the mastering the fear go and you're vulnerable. I wanted the shooting to happen in the wide shot so people wouldn't feel the setup. It had to feel as random as possible."

"What's going on in the secret of the shade is Pran's magic. He's taking over as the savior, so I wanted a kind of beauty to this moment. The Caravaggio feel is rather lovely, and the slight chiaroscuro. This is all reflected light. It's all to make the audience feel hope without being certain exactly what Pran is doing, like the characters. I could speak to Haing in French, so the other actors didn't know what we were saying. That was important because we needed to create the trust that they were physically safe as actors, but at the same time, there was a freedom in the choreography."

"This sequence had to be a giant ballet, though there was very fast cutting. The real conundrum for me was, how do I do the arrival of the Khmer Rouge and the evacuation of the city at the same time? So, I wanted to take some ordinary circumstances and make them strange, so I had people throwing down suitcases while standing on the roofs. Into that chaos, I wanted our little group pushing their car, which for me was a perfect illustration of how they were both free, but not free and how everything had switched around. Then we spent a long, long time thinking about how we were going to do the evacuation scene."

"This is a level crossing I found on train tracks. The shot and reset took 15 minutes, which gave us seven minutes to be ready for the trains to come. If you see 3,000 people carrying bags down a railway track, it doesn't bode well. Sydney and the tuk tuk they're pushing have guided us into the evacuation. There was a road that crossed the track and went into the city. I could get one flowing shot of evacuation and invasion in the same moment, and the Khmer Rouge could run into the camera and almost wipe it out."

"It's a continuing shot, and I love the idea that our perspectives are shifting with a real kind of dynamism. And then with the odd sounds [composer] Mike Oldfield, who has a particular ear for cacophonous noises, added to the score, like the strange way that helicopters batter the air, I think we created something visceral, I think really truthful. It was the only way I could express the moment in a way both real but choreographed. Otherwise, it was just going to be lots of little bits. If you were there, it would have felt like this, although in reality it took longer. But that's how film compression works."