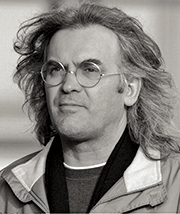

By Robert Abele

For The Bourne Ultimatum (2007), British journalist-turned-director Paul Greengrass orchestrated one of modern cinema’s most celebrated high-tension set pieces, a foot chase in which renegade American assassin Jason Bourne (Matt Damon) tracks a hit man named Desh (Joey Ansah) through a maze-like, bustling Tangier. Desh, like Bourne, is an asset trained by a secret arm of the CIA, and has been tasked with killing agency technician Nicky (Julia Stiles), Bourne’s ally in learning the truth about his past.

For The Bourne Ultimatum (2007), British journalist-turned-director Paul Greengrass orchestrated one of modern cinema’s most celebrated high-tension set pieces, a foot chase in which renegade American assassin Jason Bourne (Matt Damon) tracks a hit man named Desh (Joey Ansah) through a maze-like, bustling Tangier. Desh, like Bourne, is an asset trained by a secret arm of the CIA, and has been tasked with killing agency technician Nicky (Julia Stiles), Bourne’s ally in learning the truth about his past.

Greengrass, whose propulsive, run-and-gun shooting style echoes the jagged realism of war documentaries, always conceived of the sequence as a complex ballet of movement, drama, and shifting environment. The scene is chaotic but not confusing. “I wanted a sequence that flowed seamlessly from one kind of action in one theater to another kind of action in another theater,” he says.

Working closely with second unit director Dan Bradley, camera operator Klemens Becker, cinematographer Oliver Wood, and key choreographers and stuntpersons, Greengrass turned his detailed preproduction animatics into a live kinetic playground on the rooftops, streets, and apartments of the Moroccan city’s medina. At times that meant some deliberate public misdirection. “We’d set the crew in one place to draw the crowds,” says Greengrass, “then we’d nip off very quickly for five minutes, bang done. We were trying to fake crowds all the time to get the shot.”

Tangier is a city on hills, so you get these beautiful views. The sequence required a huge rig that took a long time to set, a couple of weeks, because we had cranes all the way along the buildings, and a Skycam that ran the length of that roof on a gigantic track. We looked for a long time to find a run where you could feel Bourne is absolutely at top pace, then throw in little difficulties like walls to vault. The run had to be continuous. You couldn’t hit a street, because I wanted to set that up as jeopardy later when he makes the jump.

I like to use zooms, which were very unfashionable, but I think I probably made them a bit more fashionable. It’s what I was brought up with. It can give you a shot like this, which slightly softens out the back and gives you perspective, makes the character feel etched. He’s running toward the camera and you feel there’s depth between the camera and him, so it makes you feel like you’re in the shot. You feel he’s got a long way to travel, which creates urgency and desperation. These first two shots set the scale of the physical challenge. But also the dramatic challenge, because you know the bad guy is hot on the heels of Nicky.

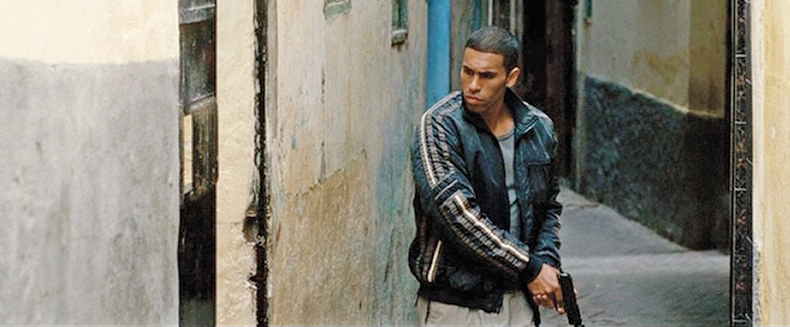

Nicky realizes Desh is after her, so she ducks off the medina into a side street trying to get away. Having her banging on doors was a piece that came together that day. To just run and open a door was a bit obvious, so we had to create more panic. Believe me, shooting in a medina in the middle of Tangier is not easy. You have to shoot incredibly quick, accurately, and move on. You couldn’t hang around in any one place for too long because the crowds were just immense.

You’re measuring these things all the time: Can she get away? Is the bad guy getting closer to her? And will Bourne catch him before the bad guy gets to her? That gives you a tremendously rich dramatic paradigm. A very important choice is varying the pace. You’ve got Bourne going at full bore, trying to get to the bad guy, but the action between Nicky and Desh has been slowed right down because they’re playing haunted house. That makes it really compelling. Action is like a piece of music. You’ve got to vary it, add new elements by degrees.

This shot shows you spatial relationship, the distance between the buildings, and the heart-stopping nature of the stunt. We slowed it down right before, when Bourne sees the bad guy go into the house, and he knows Nicky is in there. He knows he’s not going to make it unless he goes the straightest possible route. The guy has to jump all that way. A lot of the satisfaction from watching great cinematic action is when the big money moment has been prepared for. We’ve been building to this big jump, because you want that last physical act that means Bourne gets on terms with the bad guy.

This was a bloody big rig, and it took months of preparation. We needed a place that was credible as a jump but exciting, and not far-fetched. The Bourne universe is a real world, but heightened. The stuntman literally jumps straight across and down through a window, and we had a false window that could break safely. The camera operator had to go across that on a wire, in a harness, and I have a memory of the harness getting stuck and us having to stop and reset. So many issues were at stake: the fluidity of the shot, that it felt dangerous, and that you’ve got to do it safely. I think we filmed it a couple of times.

Now we take the music out, so you feel absolutely involved in the fight. I want the camera to always be trying to catch up, ever so slightly. It’s never anticipating. I want the camera to not know, and react to what the action is. The truth is that it’s a movie, so we do know. But the skill is to shoot in such a way that you create the illusion that you don’t. Does it look too knowing? Or is it so reactive that we’re not on top of what’s occurring? It’s a fine line to tread with single shot. Camera operator Klemens Becker and I have made a number of movies together, and he’s learned brilliantly to shoot the way I like things to be shot.

You must never leave a gun unaccounted for in an action sequence. The point of gunplay is to put Bourne at a disadvantage and deal with it, so that you can get down to the raw physicality of the fight. Stunt coordinator Jeff Imada designed the fight, and what you do is spend weeks and weeks designing the fight and rehearsing it. Matt would shoot all day and then come in and do three or four hours of fighting rehearsals. The fight is almost a separate set piece. Fighting is ballet. It’s physical theater, and it’s incredibly skilled. We shot some of it in Tangier, and then finished it in London at Pinewood Studios.

Jeff worked out some moves, then I’d go in and look at it and go, ‘OK, that’s good, and what if we did this?’ Then they work on that. You build it up at quarter speed, sort of blocking it at walking pace, trying to get a shape to the fight. People can get badly hurt if they don’t get the choreography exactly right. I don’t like to sell it all with cuts, either. You’re trying to put the camera in places where you can feel the true kinetic energy of two men having at each other at full-tilt ferocity, and that’s what makes this fight work. I guess it goes back to my background in documentaries. I want them covered how I would cover it if I was there.

This is when Bourne is first thrown into the bathroom. This shot does several things at once. It’s selling the space, how small it is. It’s almost the reverse of a big wide shot, it’s a tiny-cram. You read the rest of the fight in the knowledge of that shot. Secondly, it puts Bourne at a profound disadvantage for what you know is going to be the concluding sequence. This comes down to the core conception of the whole action sequence. I wanted what had begun 12 minutes earlier outside in the entire Tangier cityscape to end in the smallest room of a small house, i.e., a bathroom. A room barely big enough to swing a cat in.

You’ve got to change weapons, of course, so he has a knife. The hurdle is compounded. It’s raising the stakes against Bourne. Part of it is accentuating the fact that you’re in this small room by augmenting the sound. You’ve got a track you record, but there’s a little bit of augmentation to do with things in people’s hands, the knife and so forth. You’d augment the thuds and thumps too. I wanted the soundscape to feel that by the time you got into that small room, you were there with them.

I love this shot, where you just see that big face being mashed up with Bourne’s arm. It’s dirty and messy and violent and real. Bourne uses a towel because that’s all he’s got. It’s not like pulling out a piece of technology like James Bond would have. What can you do with a towel? Bourne shows you, turns it back on his opponent, and ends up getting it around his neck and throttling him. And the guy’s an operative too, doing what Bourne used to do. So it sets up a psychological relationship between them.

Bourne’s is a real world, so you want lighting that’s got atmosphere but isn’t noticeable. You want to light in a way that’s got real punch in the blacks, some thickness, and you’re reading the grime and the dirt and the weather of the environment. You’re probably shooting pretty high and fast stock, so there’s a bit of punch in the grain, but not so much that it draws attention. The key is for you to buy it without questioning it. Then I use a zoom for that sense of reactivity. It gives you an ability to attack the action. You get accumulated momentum and detail.

You’ve been through this whole physical experience of chasing, through the medina, up onto the roof, down through the apartments, the big jump, the immense sprawling fight. But in the end, you get to the simple dramatic truth of Bourne having killed, which is necessary, but this is where Matt is such a brilliant actor. He gives it all to you. He gives you the physicality, but also the moral component. It’s an important journey for the character. It’s slightly edgy. You have to feel that it

really happened.