BY ROBERT ABELE

Shawn Levy first saw the chess prodigy saga Searching for Bobby Fischer in its original theatrical release in 1993, when he was a film school student at USC. Sitting down in the spacious living room of his Brentwood home to re-watch it, he recalls the student film he made the following year.

“Every one of my classmates was making Tarantino derivations, and my student film was about two kids who live in a small town and get married to get into The Guinness Book of World Records. I was mocked because it was more populist and crowd-pleasy, but I know there are things in Bobby Fischer that were in my short film. And what’s crazy is now th at I look at it again, the way it informed Night at the Museum (2006) and Real Steel (2011) reveals itself retroactively.”

Steven Zaillian’s directorial debut, an adaptation of Fred Waitzkin’s book about his chess-playing whiz kid son and the joys and pitfalls of nurturing a gifted child, was a critical but only modest box office success in 1993. But over the years it’s attracted what Levy calls an “in-the-shadows” cult following that reveres it for its subtle intelligence, deep emotion, and searing insight into children and parents.

“There is something about it that is both lyrical and realistic,” says Levy. “It’s not a fanciful, built world like a Tim Burton or Baz Luhrmann film, nor does it have a kind of a cinéma vérité realism. It feels really honest about prodigies and family, yet in its music and writing and cinematography, it’s also very poetic.”

The movie opens to black-and-white stills and newsreel footage of Fischer’s 1972 world championship season, narrated by eight-year-old Josh (Max Pomeranc) over a cautiously portentous James Horner score. The brief summary of Fischer’s eccentric rise ends with Pomeranc whispering the master’s fate, on a fade to black: “He disappeared.” Then we see the title of the movie.

“It gives me chills, always did,” says Levy. “Audiences want to feel they’re in the hands of a powerful, confident, competent storyteller. Directors set our tone early; openings and closings are everything. And to me, this opening is so fantastic. My new movie This Is Where I Leave You opens with a prologue where a guy watches his life implode, and the title card is on a hard cut to black, silence, and one piano note. I hadn’t realized until now but that is my Bobby Fischer title card moment.”

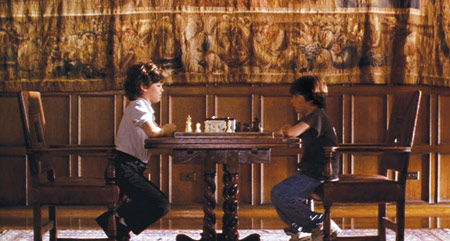

GAME FACE: (top) Levy loves the almost-wordless setup of the prodigy Josh (Max Pomeranc) with big, juicy close-ups. "You are inside the experience of the boy." (bottom) Josh at his first tournament in a school gymnasium. (Photos: (top) Photofest; (bottom) Screenpull: Paramount Pictures)

The opening touches on Fischer’s notorious genius, but as Levy points out, the story that follows isn’t about Fischer but his ghost, set up by the odd mix of childlike voice, score and documentary. “The myth of greatness looms over the whole movie now. How will the characters service that myth? Will they revere it, and think that talent demands aspiration for it? Or will they prioritize a healthy, well-rounded life?”

The first scenes of the movie set up the boy’s discovery of the game, almost wordlessly. Playing in the park with friends on his birthday, young Josh wanders off and happens upon a knight piece, then hears the sounds of men playing chess at public tables. Zaillian keeps the camera tight on hands, faces, and chessboards. Josh observes from behind foliage, mesmerized, even as rain begins to fall, and suddenly one of the players (Laurence Fishburne) silently appears, towering, holding out a baseball to trade for the knight in Josh’s hands. Even after Zaillian cuts to Josh’s bedroom later that night, the outcome of that standoff is still uncertain. The shot is a close-up on a new baseball glove, and the faces of Josh and his dad Fred (Joe Mantegna), who’s eager to introduce his son to a beloved sport.

“Notice how there isn’t a wide master shot for the first 10 minutes,” says Levy, “just these big, gorgeous, juicy close-ups. You are inside the experience of this boy. In addition to really engaging you, it declares the scale of the movie: it’s about the small things of humanity and behavior.”

Fred leaves the room, and in a slow pull back from Josh’s bunk bed fortress—with legendary cinematographer Conrad L. Hall creating a warm glow through rain, glass, and a rotating mobile camera—we see the knight still in his hands. Josh didn’t take the trade, a silent reveal that he’s chosen chess over baseball. “There’s real confidence in making the audience wait to see what he decided in that exchange. Now we know this is a stubborn kid who’s been smitten by something. And still no wide shot. It’s really bold for a first-time filmmaker.”

The next day, Josh convinces his mother (Joan Allen) to take him back to watch the chess players in the park, a few of whom appear to be on the edge of madness. But Josh soaks it all in with a beatific look on his face. Levy makes note of Horner’s gently swelling music. “I know there’s a school of thought that believes in either a minimalist lack of score, or something atonal and jarring, but here’s an example of a movie that unabashedly uses score to underline dynamics and feelings, and to me it fills out a really lush experience. It’s such an intrinsic part of the weight of the movie.”

At home, his dad wants to see what all the chess fuss is about, and Josh reluctantly agrees to a match, sitting in a rocking chair on phone books, looking childlike. Afterward, disbelieving his wife’s assertion that Josh let him win, Fred asks for a rematch. Zaillian cuts to a view of the phone books being tossed on the floor, followed by a shot that connects Josh to his gift: the chess pieces in the foreground and the kid in the background, arms and head resting on the edge of the table, his eyes taking in the board. “He wants to be at the level of the pieces,” explains Levy. It’s a different Josh that now intones, “Your move.” Zaillian makes it clear that dad is toast. “That’s kick ass!” exclaims Levy. “I know this isn’t a sports movie, but there are moments where you get those sports movie goose bumps.”

COMBAT: (top) When Zaillian introduces Josh's arch rival, "You instantly hate him"; (bottom) As the boy's hardened teacher, chess master Ben Kingsley advices contempt for the opponent. (Photos: (top) Screenpull: Paramount Pictures; (bottom) Photofest)

Convinced his son might be gifted, Fred takes Josh to the Metropolitan Chess Club—a darkly lit, musty place that suggests, unlike the raucousness of the park, Levy observes, “an old world. It’s more subdued, softer.” While Josh plays one of the members, Fred talks to a retired chess master, Bruce (Ben Kingsley), about teaching him. “Look how the sound gets his attention,” says Levy about a tight close-up on Kingsley who listens to the authoritative click-clack of Josh’s game. “Kingsley hears it, doesn’t want to look up, but can’t resist. It’s beautiful. I love how God-given talent announces itself.”

It’s back to the park, where Josh’s ebullience playing the swaggering Vinnie (Fishburne) is in full swing. Included is a shot in which the actor clearly hits the speed clock button and hurts himself. Levy says, “That was absolutely a mistake. When you direct any movie, but especially movies with kids, you hope for little mistakes. You can see he really pinched himself. But Zaillian left it in because all these little accidents accrue to build authenticity.”

In a bedtime scene at home in Josh’s bunk bed fort, he asks his mom if the homeless Vinnie can stay with them. She tells Josh he has a good heart. Levy comments on the fact that in this supposedly key moment, underlining Josh’s good nature, Horner’s music is absent. “I’ve never noticed that before. The movie is pedal to the metal in scoring the mythology of the game, and anything to do with his talent, but it has not once scored emotion or sentiment—either here or when he didn’t want to beat his daddy. We’ll see if it holds up.”

For Josh’s first tournament, set in a school gymnasium, we hear a supervisor’s admonishing voice explaining proper behavior over a pan that reveals it’s the nervous parents getting the lecture. For Levy, this bit of humor—lit with plenty of atmospheric shadow, as are a lot of the film’s interiors—helps keep the movie from being pigeonholed. “It’s not a comedy, but it’s comedic. You wouldn’t call it a drama even though it’s poignant. I’ve spent a lot of my career wrestling with the legitimate exigencies of tone. In my early movies, I’d get in trouble for lighting comedic scenes moodily. There’d be calls from the studio, ‘What are you doing? Lighten it up!’”

Zaillian pulls another delayed reveal regarding the outcome of the tournament, cutting from the parents clutching the bars of the equipment locker where they’ve been sent to wait, to the train ride home, to a sleeping Josh holding the trophy. A montage follows of Josh winning, winning and winning, but more importantly, showing the happiness he and others feel. Levy remarks, “This is basically the sports montage, but the super classy, elegant version. Usually a montage is an informational fast-forward, but this imparts feeling, too. And it’s not to a pop song, it’s the score.”

Things take a turn when the film introduces Josh’s rival, Jonathan Poe (Michael Nirenberg), a serious-looking boy in a white polo shirt with a “trick or treat” tagline for the opponents he beats. “Young Fischer,” he is called by a spectator watching him play. “You instantly hate him,” says Levy. “He’s glaring, humorless. They’re setting up the villain.” When he shows up at the club, the boys size each other up, which Zaillian captures like a Western, with countering dolly moves. “It’s all done with a very long lens, so you’re really reducing focal depth. It’s like they’re the only two things in the world, so everything in the foreground and background is blurry. Josh, who’s taken his own talent casually, seems threatened by someone who might be better.”

Fearful of losing the respect and love of his teacher and father if he chokes, Josh throws his next tournament. Fred admonishes him afterward outside in the rain. Zaillian underscores the tension by shooting them through iron bars. “They’ve become imprisoned by this game, by their expectations and fears. Fred realizes he’s becoming more like a coach than a father, and that’s not the relationship he wants with his son.”

HOMEFRONT: The loving father-son relationship is threatened when Josh's dad (Joe Mantegna) succumbs to his own competitive nature and tries to turn him into a winner. "They've become imprisoned by this game." (Photo: Photofest)

As Bruce gets ready to lecture Josh about the need to feel contempt for his opponent, Zaillian gives us a long shot of their exchange. “It’s great lighting,” says Levy. “The boy is in light and the master is in dark. Josh doesn’t feel hate for his opponents.” Afterward, Zaillian communicates an entire tournament in one shot: an auditorium door opens, revealing a trophy ceremony for Jonathan as Josh and his dad hurriedly walk out, the door slowly closing after they leave the frame. “It’s a great shot. Visually we see it’s becoming not fun for him; the joy is drained out of it.”

At home, things come to a head when Josh’s mom and dad argue over him. The scene ends with the mother threatening to take him away if his decency is compromised, as she walks out and slams a door behind her. “No score again,” says Levy, “just one pan where she’s in a big close-up, and it gets progressively intense. Not through editing, but through proximity to the lens, so there’s nothing between you and the fierceness of her feeling. It’s beautiful. It’s also what everyone wants to feel from their mother, that they would protect what’s good in them against everything else.”

Eventually, Josh accepts the notion of playing for himself, not for anyone else. As the movie’s final tournament scene approaches, Levy talks about “big game” tension. “In Real Steel, we had a five-round final fight, and figuring out how much you can service without exhausting an audience really matters.”

In an atypical move, Zaillian opens the final competition inside a large medieval-style hall from Jonathan’s point of view at the table, looking out to where he thinks Josh is in the crowd of chess-playing kids, only to discover that Josh is not there; he’s like a disappearing and reappearing antagonist. Levy is abuzz at the way this series of shots compress many rounds of competition into a psychological extrapolation of gathering tension. “That’s a really cool way of telling the story of the finale: putting Josh through five matches with a point of view that keeps showing an empty chair, and suddenly Josh is closer to the lens every time. Zaillian made it about the fear of the villain as his greatest threat approaches.”

The last match is a victory not only for Josh’s chess smarts, but for his kindness. Knowing he’s got Jonathan beat, he offers a draw, which his opponent doesn’t accept. Horner’s score swells appropriately in the aftermath, but the movie’s last scene is quieter, a hint of the man to come: Josh walking amongst fallen leaves with a new tournament friend, who we last saw getting a stern post-defeat lecture from his dad. “Want to know a secret?” Josh says, “You were a much stronger player than I was at your age.”

“This is such an unusual ending,” says Levy. “He sees the joylessness in this kid. It doesn’t end with the triumph, or with him with his parents and teachers. It ends with him being a good person. I love it; I can’t believe it still gets to me. It doesn’t feel precious, sentimental or cloying. It’s just moving, and beautiful, and true. It’s about talent, and parenting, and the way we’re shaped by the various influences in our lives.”