BY DAVID KRONKE

It's safe to say that a sizable number of Gen-Xers spent more of their childhoods watching the sitcoms of Jay Sandrich than they did in the presence of their parents. One of the living legends of television, Sandrich directed most of the series runs of The Mary Tyler Moore Show (1970-1977), Soap (1977-1979), and The Cosby Show (1984-1992), as well as spinoffs and multiple episodes of dozens of other shows. He was nominated for nine DGA Awards, winning three times, and received four Primetime Emmys.

Marcy Carsey, who developed Soap and worked with Sandrich on Cosby, says, “He was the best director we ever worked with, by far. We offered him everything first and he turned down most of it. His process of directing seemed effortless. He had a rare combination of an easy way and a firm hand. The best parenting is firm and gentle. The best directing is, too.”

“He was so good,” recalls Allan Burns, co-creator of The Mary Tyler Moore Show. “He would take your words and make them better than they were. His blocking and physical business was so good that an episode would improve by 20 percent.”

Yet, to this day, Sandrich declares, “I wasn’t a creative person; I never was.” Although his father Mark directed Holiday Inn (1942) and a number of Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers musicals including Top Hat (1935), Sandrich says he wasn’t bent on entering the family business. “I didn’t feel a calling for directing. I’m not like a lot of young people today who have cameras and shoot films and know this is their love.” Of his early days on I Love Lucy, he maintains, “I didn’t know anything.” His modesty-versus-resume ratio is staggering.

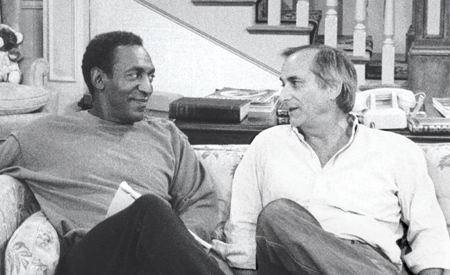

Jay Sandrich kicks back with Bill Cosby on the set of The Cosby Show in 1985.

Reflecting on his celebrated career from his spacious condo overlooking Marina del Rey, Sandrich says, “What helped me in my career was, one, being able to read a script and two, casting.” He deflects his contributions as a director by saying, “I never believed that an audience watching a comedy show should ever say, ‘What an interesting angle!’ If they’re starting to notice the camerawork, then they’re missing the writing and the performances.” Again, the modesty belies the accomplishments.

Sandrich remembers his father’s friends Jack Benny and Irving Berlin among houseguests in his youth. Mark, a former Directors Guild president, died in 1945, and when Sandrich attempted to enter the business, people who had admired his father (including Lucille Ball) helped him on his way. He broke into the business as an assistant director on I Love Lucy (1956) and The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour (1957) before moving on to Make Room for Daddy (1957), and The Dick Van Dyke Show (1961).

It was at I Love Lucy where Sandrich met the first of what he calls the three mentors in his career—assistant director Jack Aldworth.

“Jack taught me how to run a set,” says Sandrich, who took his mentor’s job when Aldworth was promoted to associate producer. “I remember the first day I was in charge of the set. I didn’t know the cameraman was going to tell me when to roll camera. When we were on location, I didn’t know how to organize crews.”

On The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour, Sandrich’s greenness was overshadowed by other on-set drama. “I was so young and caught in the middle of America’s favorite couple breaking up,” Sandrich says of Ball and Desi Arnaz’s deteriorating marriage. “Psychologically, I didn’t know how to handle it because I was in the middle. They all were wonderful people but naturally there was tension.”

Sandrich escaped after the show’s first season for Make Room for Daddy, where he met his second mentor, the esteemed producer-director (and longtime DGA secretary-treasurer) Sheldon Leonard. “I learned through Sheldon. He had a wonderful story mind, he really examined things.”

And though much of early TV was visually static—it was initially described as “radio with pictures”—Sandrich remembers, “Sheldon realized that you had to keep moving people on audience shows, so I started to not be afraid of camera movement. A lot of directors would come in and were afraid of moving people because they weren’t sure how to move cameras. Sheldon taught me, ‘Don’t be afraid to move the actors; the cameras will follow.’”

Leonard also assigned Sandrich to work as associate producer on The Andy Griffith Show, “which meant I put the laugh track in,” he explains. “It also got me to work with the editor. So even though I wasn’t a director yet, I was spending a lot of time in the editing room and I got to understand editing. It was a wonderful chance to see what a good editor did and to see what a director should get [in terms of coverage]. It’s very important for anyone who directs audience shows to be able to edit.”

And even though Leonard once famously yet incorrectly told Sandrich, “Someday you’ll be a good producer but you’ll never be a director,” he gave him his first directing job, on The Bill Dana Show in 1965.

Sandrich’s next mentor was another Leonard, Leonard Stern, who hired him as lead director on a short-lived, ahead-of-its-time sitcom, He & She (1967-1968) and as an associate producer on Get Smart, giving him more valuable time to observe the editing process and letting him direct a number of episodes. “I’m not sure I would’ve survived as a director if not for Leonard,” Sandrich admits. “He constantly promoted me and gave me chances to work.”

It was during his time on Get Smart when Sandrich realized his future laid in directing, not producing. “What’s fun for me is being on the set working with actors,” he explains. “Not in working on scripts, not worrying about [building] sets for next week or having a story for three weeks from now. I loved getting on the set and working with actors.”

For that, Sandrich credits He & She star Richard Benjamin, who gave him invaluable insight into the actor’s process. “I should’ve taken an acting class, but I never did,” he says. “It took me a tremendous amount of time to gain the confidence that I knew what I was doing. Richard would say to me, ‘Why am I saying this line?’ I’d say, ‘You’re saying it because you’re setting Paula [Prentiss] up for the joke.’ He’d say, ‘But why is this character saying this line? It doesn’t make sense.’ So we would try to find a way to make that moment honest, not simply a setup joke. I had never worked with an actor who questioned character motivation so closely.”

Above: Sandrich and the Cosby season one cast with special guest star Lena Horne. Below: Sandrich on location at the University of Pennsylvania for a 1986 episode of The Cosby Show. (Photos: Courtesy Jay Sandrich).

Before long, Sandrich had mastered an economic, unfussy style of direction that focused on comic reactions. “I eventually adopted the philosophy of matching close-ups and matching over-the-shoulders,” he recalls. “I always liked to have the same size close-ups or same size over-the-shoulders. I didn’t like to go from an over-the-shoulder to a close-up. It would be close-ups on both of them. I learned from one-camera editing that you need reaction cuts.”

“He has a certain magic for the multi-camera style,” says Burns, who wrote on He & She and championed Sandrich for The Mary Tyler Moore Show. “He was really good with cameras. Three-camera shows were pretty static looking, with a huge proscenium; no one shot anything tight. Jay did. Jay moved the cameras in so you would get the expressions. Even his masters were not really wide. That’s the look he liked.”

Mary Tyler Moore transformed Sandrich from a working director to a genius. Of course, he credits the writing. “When you create characters and humor, nothing is more important than that,” he insists. “I never did many pilots because I couldn’t find many scripts I liked. It was just a matter of choice; I had to like the script. I thought this was one of the funniest scripts I had read: it was real people, talking. It may not be funny on the page, but if cast it right, it would be great.”

Casting runs a close second to writing in successful directing, Sandrich adds. “When I was directing, directors were always involved with casting. The writer/producers are really thrilled when someone comes in and reads their lines correctly and gets a laugh; they want to cast that person. My feeling always was, number one, how are they going to do six weeks from now, and number two, what happens when the script isn’t as good? I cast in terms of thinking of a show being on for years, not just for that pilot script.”

CBS, who had bought the show on Moore’s popularity, wasn’t as wild about Burns and James L. Brooks’ pilot script and wanted them fired, and wanted Ed Asner (as the iconic grump Lou Grant) and Valerie Harper (who played the wise-cracking neighbor Rhoda Morgenstern) recast, and was already working on a series to replace the show on the schedule. But Grant Tinker (Moore’s then-husband), who owned the production company producing the series, refused any creative changes. The network demurred.

According to Sandrich, that represents a huge difference from the way network TV sitcoms work today. “There’s too much interference today and there’s a certain sameness to shows,” he says. “Back then, the network was in charge but independent producers were making the show. There was nobody like Grant Tinker. He’d say, ‘This is the show we made and we’re not going to make a different show.’ He really believed the creative people who had the idea were more in touch about what the show was about than the network. The networks now say to the producer, ‘If you want the show on the air, we’re going to take 50 percent.’ The big difference is companies then really would stand up and fight.”

One of Sandrich’s challenges that first season was cajoling Ed Asner into accepting the show’s humor. “He takes acting very seriously and thinks so seriously about what he’s doing,” Sandrich says. “And sometimes you have to get an actor to pick up speed or not be quite so literal. Part of a comedy director’s job is to keep them truthful but funny.”

Burns concurs: “Ed slowed things down; he would labor over words. Jay would say, ‘Ed, fast is good.’ Ed would really get pissed off but Jay was like a dog with a bone, he would not let him slow down. Jay got that performance out of Ed and it won him an Emmy that year. No one expected that.” For the record, the other people CBS wanted jettisoned—Harper, Burns and Brooks—won Emmys the first year, as did Sandrich.

Mary Tyler Moore’s series finale in 1977, in which all the characters except resident idiot Ted Baxter (Ted Knight) lose their jobs, set the benchmark for the finale of a beloved series, with some help from Sandrich and his cast who massaged the final scene.

The writers didn’t want to write it because it was the last scene of the show,” Sandrich recalls. “So we worked with three-quarters of the script for most of the week. Wednesday we got the scene, and it was an OK scene, but it didn’t involve the whole cast and it didn’t have enough emotion.” He beseeched Brooks and Burns to rework it, and they did. “It came [together] so fast. We added certain little things, such as the group shuffle to the tissue box, but it worked. In the first rehearsal, Lou Grant said his line, ‘I treasure you people,’ and tears came to all of our eyes because we knew we were saying goodbye to each other.

LAUGH OUT LOUD: During the 1970s, Sandrich directed most of the series runs of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, and Soap, as well as episodes of The Bob Newhart Show. (Photos: Photofest/Getty)

“I told him, ‘Don’t read that line that way again until the show.’ When we did it for the writers, I told everybody, ‘No emotion, because we can’t do this. It’s there, but you just have to trust us.’” The cast delivered at the taping, and the final scene was done in a single take, though everyone on the show was weeping so copiously the lighting guy forgot to turn out the lights in the newsroom when Mary did (Sandrich fixed it in post).

Soap, a then-racy parody of soap operas, was Sandrich’s next triumph, and his most unusual. Despite the spate of Norman Lear hot-button sitcoms in the ’70s, it was unusually controversial (many Southern stations refused to air it until it became a hit), and it was the first series where Sandrich really paid attention to the show’s visual palette.

“Soap was the most difficult,” he agrees. “We had so many sets, we’d have to put sets behind sets that the [studio] audience didn’t see [except on monitors]. We had 16 permanent characters. No show had ever done that. It was the first taped show I did; I’d always done film. So I wanted to find a lighting director who came from film; I wanted someone who could handle it.

“At the time, the top taped television shows were like All in the Family; a lot of light, no shadows. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it was a different style. I wanted to go back to shows that looked more like the filmed shows, and even go dark in spaces. We were fortunate to find a wonderful lighting director, Alan Walker. Soap was the big departure for me. They allowed us to spend more money on that series than any program I’d ever worked on.”

Carsey says the investment paid off. “There’s never been a better looking half-hour, ever. That’s where I first saw Jay work up-close. He was a master of the technical stuff, too, without making a big deal of it.”

Sandrich directed a single theatrical release, Seems Like Old Times (1980), written by Neil Simon and starring Chevy Chase and Goldie Hawn. But the glacial pace of filmmaking quickly sent him back to TV.

“That’s why I didn’t stay in features,” he says. “I loved the people I worked with, but I didn’t like that we only used one camera. We’d get a master shot, you get the scene working and the cameraman would say, ‘OK, we’ll be ready in an hour, hour and a half,’ and every light would come down. You’d do a close-up or an over-the-shoulder shot and do one more shot and then it was time for lunch. Out of a day’s work, most of my time was spent playing backgammon. The pace was just not the pace for me. I didn’t care that much about my art of getting a certain shot. I love the feeling of working all day and finishing a show and starting all over next week. So I went back into television.”

Which led to perhaps his biggest hit, The Cosby Show. Carsey, who Sandrich recalls as a tireless friend on Soap, asked him to shoot a demonstration reel without a script for NBC affiliates. Sandrich, who only worked if he loved a script, resisted but finally relented; he was offered the series, now fast-tracked to shoot in New York.

To that, Sandrich replied, “It’ll shoot in New York without me.” Fortunately, his wife Linda, a native New Yorker, begged him to reconsider and was instrumental in him accepting the job.

Cosby was a huge hit, although, like Soap, it was different from the way Sandrich was accustomed to working. “That was more about casting—the importance of Bill and that whole cast—and then the writers.”

Sandrich remembers Cosby as a mercurial talent—he could be brilliant or not so much, and Sandrich had to prepare for both scenarios. He credits Cosby’s onscreen wife, Phylicia Rashad, with rescuing many an episode.

“Bill didn’t always memorize his lines, and even if he did, he’d sometimes have a little trouble finding them,” Sandrich says. “So, to get rid of the pauses or get back on script, I’d start with a close-up on Bill, cut to Phylicia and place Bill’s lines over her. She was always in the scenes, reacting. Whatever needed to be done, she was doing.

“On The Cosby Show, because we didn’t always have enough rehearsal time and Bill didn’t always get the lines exactly right, I realized I couldn’t do two-shots. I had to do many more close-ups than I was used to so I could edit. If I had two-shots and there was a problem, we couldn’t edit. When I look back on the early years of The Cosby Show, I think, ‘Oh, god, there are so many close-ups,’ but I had to do that for editing.”

But Sandrich also credits Cosby with creating a lot of magic. “Bill came in one time and said, ‘I want to do a show for 4 year olds.’ We said, ‘Huh?’ He said, ‘I want to do a show for fans of Rudy [his daughter on the show].’ So we did a show where she’s having a sleep-over and Phylicia is busy that night so Bill gets the kids together and starts talking to them.”

All went well, until it was time for the second taping. (Sandrich preferred shooting entire episodes before two different audiences, one in the afternoon and one in the evening, rather than subjecting one audience to four hours of retakes, as is the practice today.) So the second time around, “The kids started answering the questions before Bill asked them or they started laughing because they knew it was funny. And I said to Bill, ‘We’ve got a little problem here. What we better do is keep a camera on you, and you just ask them any questions you want. So Bill asked entirely different questions during the show and it was hysterical. We got so much reaction from people who loved that show. And this is how you’re a brilliant director—you have Bill Cosby.”

Suggest to Sandrich that the ability to divine great scripts from those that are lacking, and to coax actors to great comedic performances are, in fact, considerable achievements, his humility prevents him from taking the credit he so richly deserves.

“I worked with some of the best comedy writers there are,” he says. “And sometimes even they didn’t get it right, but I wouldn’t come to them with lines. I’d say, ‘What if … ?’ I didn’t always know how to solve it; I just knew what the problem was. I didn’t know how to tell an actor how to be funny. I could say what I thought was missing or another approach to it. I guess you can call that creative. I call it interpretive.”