BY BETSY MCLANE

No one could ever say Les Blank hasn’t done his own thing. An icon of independent filmmaking, his work—40 films over 50 years—is considered one of the finest celebrations of American life and culture ever captured on film. Blank is the subtle detective, musicologist, and gastronomic adventurer who takes audiences inside worlds of food, friends and music. He has immersed himself in everything from the blues in The Blues Accordin’ to Lightin’ Hopkins (1968), to Cajun life in Spend It All (1971), the norteño music of the Texas/Mexican border in Chulas Fronteras (1976), Polish-American devotees of the polka in In Heaven There Is No Beer? (1984), and the customs of the Mississippi Delta in Yum, Yum, Yum! A Taste of Cajun and Creole Cooking (1990).

An auteur in the fullest sense of the word, Blank is the driving force of all of his films. In addition to director, he is fund-raiser, producer, casting director, cameraman, editorial and music supervisor, as well as copyright holder and distributor through his Berkeley-based Flower Films. His work has won numerous awards, and has played in both major film festivals and tiny regional theaters. He is legendary for personal appearances at screenings, sometimes cooking food to enhance the experience, as he did when he had a big pot of “the stinking rose” bubbling in the theater to accompany showings of Garlic Is as Good as Ten Mothers (1980).

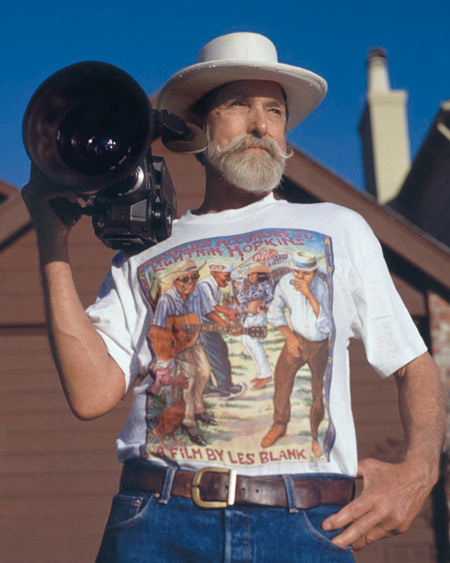

COLORFUL CHARACTER: Blank has always taken a hands-on approach to documenting unusual subcultures.

COLORFUL CHARACTER: Blank has always taken a hands-on approach to documenting unusual subcultures.When asked where his interest in what some would consider odd subcultures comes from, Blank answers with his typical unassuming humor. “Probably laziness,” he says. “Curiosity.”

Growing up in Tampa, Blank saw distinctions between his own privileged middle-class home and the lives of African-Americans, Cubans and other Caribbean émigrés. Although his parents didn’t want him playing with the poor kids, Blank found families who were different and more interesting—especially the exotic meals they ate. An old barn called the Florida State Ranch in the middle of the woods, where people drank, drove pickup trucks and carried shotguns, became a favorite hangout. With lively music for dancing and exuberance that sometimes resulted in parking lot fistfights, the sights, sounds and smells made a deep impression on Blank.

His curiosity landed him at USC Film School from 1960 to 1962. Although he had written plays and studied theater at Tulane University, he had never before made a film or been interested in photography. As a teenager he had been captivated by Vittorio De Sica’s neorealist classic, Bicycle Thieves (1948). “It took me deeply and intensely into the life of another person and the travails and joys of their life. It gave me a whole new way of looking at the world,” says Blank, who could be describing his own films.

The hands-on experience at USC made Blank determined to learn everything necessary to become his own cameraman. That way, he says, “I wouldn’t have to communicate what I wanted as a filmmaker to another person and have my original thoughts misinterpreted.”

While attempting to break into the industry in Los Angeles, Blank did camerawork for industrials and an independent feature about the teenage drag racing scene in Long Beach. But show business and Blank did not make a good match. Drawn to hippie culture and folk music, he borrowed a camera to document one of the first love-ins in Los Angeles on Easter Sunday 1967, which became God Respects Us When We Work, But Loves Us When We Dance (1968). Blank bargained with the local PBS station to shoot it for them if he could retain rights to the negative, thus establishing the artistic/business model he continued to follow throughout his career. “You go out and find some interesting people,” he says. “You get to know them and film them, and you make something that says something about who they are; you learn to make movies that have some meaning.”

YOUNGER DAYS: Blank learned how to operate his own camera so his vision wouldn’t be misinterpreted.

Blank’s method is basically to lay back and observe, and hasn’t changed much since he started. He just watches what unfolds and does not tell anyone what to do. Since he is the cameraman, and the crew is usually one or two other people, there is no need to “direct” the action. “He gets his shots always perfectly placed,” says documentary director Harrison Engle. “His camera moves whenever appropriate, and lingers when that will best make a point.”

Adds Blank, “I get so wrapped up in trying to tell the story as well as I can to get the best possible points of view and show the culture, that I let that be my main force of action, and leave everything else behind. I tend to get over my self-consciousness; I might have a beer or two with the people there, especially if they’re sympathetic.”

It may sound easy but creating the kind of intimacy Blank does with his subjects is not simple. Case in point: When Blank was making Spend It All early in his career, someone told him “if you want to show Cajuns doing what they like to do, go out to one of those country quarter horse racetracks where they have very few enforcements by the state, and you’ll see the real Cajun life.”

What they didn’t tell him was that in this insular culture a stranger might not be warmly received. “Some guy came up and asked me a few questions and said, ‘As soon as you turn your back on me, buddy, I’m gonna stick my knife in it.’ So I try to have a connection wherever I go to explain to others what I’m up to.”

As his work testifies, Blank has made a fine art out of making a personal connection with diverse people. He works through the lens, behind the camera, never drawing attention to himself. He makes friends with his subjects, spends weeks with them and acknowledges their dignity. Ultimately, it’s his affection for his subjects that allows him to get beneath the surface. For example, in The Blues Accordin’ to Lightnin’ Hopkins, “Lightnin’ is playing a duet with [harmonica player] Billy Bizor,” recalls Blank, “and Billy is crying his head off into a towel about the girlfriend who left him. You know it’s an act but there’s something about it that’s real, that’s not completely hokey; this man has suffered from troubles in the past and Lightnin’ is expressing his sympathy by the music he’s playing and the expressions on his face. Then the film cuts to a barbecue [joint] and a long-handled shovel scrapes out the hot coals. There’s something that clicks in all that, and I think some kind of love [is] being revealed and celebrated.”

Some of his films are the only record of now disappeared regional histories. “It’s about adding my two cents to the knowledge of the world of what makes it tick emotionally, intellectually, historically. Some of the things I have unearthed are not found anywhere else.”

He admits that sometimes he knows nothing about the culture he’s entering and relies on the generous help of folklorists, ethnographers and the local people. “When I’m hearing music, I’m trying to imagine what kind of visuals might enhance it,” says Blank. “And likewise when I’m seeing something that strikes me as particularly beautiful or meaningful, I’ll hope I can find some music to visually and emotionally bring it all together into a kind of fusion of aesthetic beauty and depth of meaning: the communication of some kind of universal truth.”

Blank’s best-known film is probably Burden of Dreams (1982), about the making of his friend Werner Herzog’s epic Fitzcarraldo (1982). A shared love of foreign cinema brought the two directors together at a screening of Herzog’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser at the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley in the mid-’70s. They traveled in Germany together, and when Herzog started work on Fitzcarraldo, he invited Blank to document the adventure. Blank and collaborator Maureen Gosling twice visited the location in the Amazon, staying for a total of about four months, capturing Herzog’s efforts to transport a steamboat over a mountain pass as well as the beauty of the indigenous culture. It was exactly the kind of mad but inspired enterprise that always captured Blank’s imagination.

Herzog compares Blank’s films to music in their ability to console. Expressing his admiration for his work, he says, “Blank is the one who has found [truth], and every single film he has made, he has shown us and given us this feeling of what truth on a screen can be. What would America be without Blank’s warm, dignified and wonderful look into the very soul of all of us?”