BY JEFFREY RESSNER

Photographed by Scott Council

A sun-baked Tom Hanks is trapped on a desert island and makes best friends with a volleyball in Cast Away (2004). Michael J. Fox zaps back in time where his future mother develops a crush on him and his father-to-be struggles to achieve his destiny in Back to the Future (1985). And a slow learner named Forrest Gump ponders the mysteries of life’s diversity within a box of chocolates while he follows the path of history in the last half of the 20th century.

Over the past five decades, Robert Zemeckis’ films have looked back at the past and forward to new ways of telling stories. He has earned a reputation as a tech-savvy auteur whose work has explored special effects and digital magic. Yet his most visually stunning film --the live action/cartoon hybrid Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988)-- used conventional 2-D animation combined with clever prop gimmicks and other low-tech trickery to achieve its eye-popping film noir look.

Despite his excursions into performance-capture filmmaking with The Polar Express (2004), Beowulf (2007) and A Christmas Carol (2009), Zemeckis, a graduate of USC film school, considers himself an old-school director who values story and character above all else. His most recent feature, Flight, tackles weighty subjects such as substance abuse, poor parenting, and the value of faith, among other serious issues.

The 1995 DGA Award winner for Forrest Gump and a 1989 nominee for Roger Rabbit, Zemeckis has had an unconventional career. Even with a seemingly “traditional” film like Flight, he continues to challenge audiences. When we spoke, he was leaving that evening for Korea and Japan to promote Flight, having learned early on that marketing, too, is an important part of the director’s job. Meeting at the Directors Guild headquarters in Los Angeles, he was more than happy to discuss his past, his present, and of course, get back to the future.

JEFFREY RESSNER: Were did you see your first movies, and whose work touched you early on?

ROBERT ZEMECKIS: I grew up on Chicago’s South Side in a working-poor family, so I watched everything on television. It was like my window on the world. But we also went to the movies pretty regularly; mostly on Tuesdays, because that was Ladies Night and my mom could get in for free. Sometimes on a Saturday, I’d go see a triple feature. I didn’t know anything about directing when I was a kid. I knew Alfred Hitchcock, of course, because he was on TV, and he was probably the one director I followed. But I mostly saw the movies starring all the action guys; anything with Steve McQueen or John Wayne.

Q: Was there any single film that inspired you to think seriously about movies as 'art'?

A: I was probably 15 years old and everybody at school was raving about this great bloody massacre at the end of Bonnie and Clyde, so I talked my father into taking me to see it. I had the experience of feeling very emotional when Gene Hackman’s character was dying, and that’s when I realized that there was immense power involved in all of this. At the same time, I had an inspiring English literature teacher, and I started to understand drama, the three-act structure, different characters, and the rest. That’s also when I learned there were writers and directors, and that movies had to start from the written word. I became obsessed and wanted to know everything I could about movies: I read whatever I could get my hands on. I remember buying Film Comment with Bonnie and Clyde on the cover, but I didn’t understand a single thing they were writing about. Then I started making my own movies.

Q: You were part of that early wave of successful USC film school students in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Did your formal education have much value, or is directing really something that comes more from practical experience?

A: I knew all the mechanical and technical stuff before I got there, because I was fortunate enough to get summer jobs at a local commercial film company during my last two years of high school. By the time I started my freshman year at college, I already knew how to sync-up sound, how Moviolas worked, how to splice film and the other things, so I got to concentrate on storytelling. But film school was great for three reasons. You got to make movies relatively inexpensively. Another was that--remember, these were the days before video--we’d watch four movies on Saturday and four more on Sunday. The film school was in a shabby little horse stable and we were sitting on folding chairs, but we were still watching classic movies projected and without commercials. The greatest part by far, though, was being in a pressure cooker environment with people who shared a similar passion for movies. That was all you talked about all day long, 24/7.

Q: Directors such as George Lucas preceded you at USC, so you must have had the added advantage of knowing you might realistically turn your passion into a paying job?

A: USC Film School always had a real sense of drama and lineage. John Milius called it ‘the long celluloid line.’ I remember coming into my very first production class on the first day and no teacher was at the front of the room. Everybody just assembled there, the lights went down, and they projected Lucas’ THX 1138. Then the lights came up and the teacher came out and said, ‘This is one of our films; this is by a student. So this is what you guys have to do now: Make movies like this.’ They were wild times.

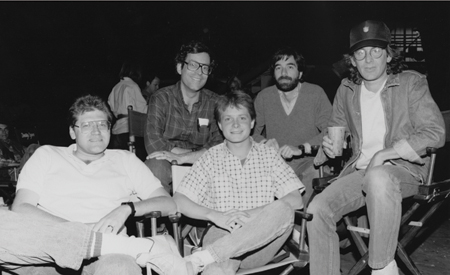

The young team on Back to the Future: Zemeckis, Bob Gale, Michael J. Fox, Neil Canton, and executive producer Steven Spielberg. (Photo: Universal/BFI)

The young team on Back to the Future: Zemeckis, Bob Gale, Michael J. Fox, Neil Canton, and executive producer Steven Spielberg. (Photo: Universal/BFI) Q: Steven Spielberg was an early mentor and has produced six of your films. When did you first meet him?

A: He brought his first film, The Sugarland Express, to show to our class. I couldn’t believe how young he was and what a huge, beautiful movie he had made. It was shot in Panavision, Vilmos Zsigmond was his cinematographer, and Steven was almost my age, just a little bit older. I was like, ‘Man, this guy is my hero!’ I buttonholed him right after class and told him, ‘Hey, I want you to see this student film I made.’ He said, ‘Yeah, great, call my office.’ So I called him up and he set up a screening room at Universal and we watched my movie. He loved it, and we stayed in touch. Meanwhile, John Milius made a deal for Bob Gale and I to write 1941 for him. John and Steven were good friends and, after we wrote this script, Milius gave it to Steven who then said he wanted to do it. So Bob and I went to Alabama, where Steven was shooting Close Encounters, and he began doing 1941 rewrites with us on nights and weekends. It was a great time. [Franois] Truffaut was there, Richard Dreyfuss, and all these other guys. In those days, everybody really became cheerleaders for each other.

Q: You had a pretty rocky start. Your first two films, I Wanna Hold Your Hand (1978) and Used Cars (1980), did poorly at the box office. What did you learn from those experiences?

A: Well, I Wanna Hold Your Hand and Used Cars were absolute failures at the box office. Complete disasters. I learned some sad news: it’s not an automatic thing that, if you make a good movie, everyone wants to see it. We had the most spectacular previews on I Wanna Hold Your Hand. It tested with really high numbers. The biggest lesson I learned on both of those projects was that a filmmaker’s job isn’t done when you’re finished making the movie. You have to really get involved in the marketing. I still remember the first marketing meeting for I Wanna Hold Your Hand where this guy said, ‘So, what do you want us to do?’ I thought, ‘Uh, oh, this is a thing, I have to go home and start thinking of some TV spots.’ I realized then that the studio really wasn’t some big happy family where everybody was watching everybody else’s back. Just because you were making a movie at a studio didn’t mean the studio had any interest in it.

Q: Did the success of Romancing the Stone (1984) turn things around for you?

A: Yeah, that was a very fortunate thing for me, and I knew it was the whole ballgame. By that time, I’d had a three-year dry spell, and all I got were offers to do teen movies and other projects that weren’t very good. I can’t thank Michael Douglas enough for the courage that he had. He said, ‘I want this guy’s style, this guy’s energy, in my movie.’ He went to bat for me, because obviously hiring me was a real [risk]. The script had the characters, the tone, some good lines and gags, but it really wasn’t a story. It just sort of laid there. I knew how to pull it all together so that everything drove to a climax.

Zemeckis, working with Tom Hanks and Robin Wright, used characters rather than dramatic conventions to propel Forrest Gump. (Photo: Paramount/ImageMovers)

Zemeckis, working with Tom Hanks and Robin Wright, used characters rather than dramatic conventions to propel Forrest Gump. (Photo: Paramount/ImageMovers) Q: Your next film, Back to the Future, gave you a bit of a reputation as a technology visionary, despite the fact that it wasn’t really an effects movie.

A: Actually--and I’m telling you the absolute truth--there are 30 effects shots in Back to the Future, and most of them are lightning. But it’s a science fiction story, so everyone thinks it’s filled with special effects. There are only a few: the flying DeLorean at the end, some fire trail stuff, maybe ten shots of time travel effects. The rest is all lightning in the sky. ILM did the effects, but those were the days when effects were pretty rudimentary. They brought out the old VistaVision camera, and it wouldn’t pan, tilt, dolly or move--the camera was locked on the tripod. It was perfectly still, because in those days we didn’t have motion control or anything like that. They were all optical shots, obviously. The big thing was inventing the effect of the time portal opening, all of that animation. Everything had to be storyboarded out very elaborately.

Q: Why do you think the film was so successful?

A: Bob [Gale] and I knew our screenplay was really, really good, even though everybody rejected it, numerous times. It was just so tight, the kind of thing that I love. Everything is set up, everything is paid off. There’s only one scene you could argue isn’t propelling either plot or character, which is when the movie stops for Michael to play ‘Johnny B. Goode.’ But every line of dialogue, every beat, every cut, every shot is doing what movies are supposed to do, which is propelling the plot or establishing character. There’s not a single extraneous frame.

Q: Who Framed Roger Rabbit combined live action with cartoon characters. How did you work with Richard Williams, the animation director?

A: That’s a good question. When Richard realized that all he had to do was animate, and that I was making the movie, it was like he was liberated. He didn’t have to do the storytelling, the shots, or the layout. He could just draw Roger and any other character he wanted--Droopy, Baby Herman--and inspire his team of animators. It turned out to be a perfect collaboration. Talking to an animator is just like talking to an actor. At least that was my experience, and that’s how I would direct them. They would do just what an actor would do, which is to see what’s written, to see what’s needed, and hear my interpretation. Then the really great animators--and I had all great ones on Roger--take that and interpret it their own way and make it even better, in that they would actually draw their performance.

Q: What about working with live actors? Have your techniques evolved over the years?

A: Certain actors have their own process, but I approach it the same way I always have, which is to take them into a room, talk, and go through the script line by line by line. It’s like a pyramid: You start at the top with your leads, and they get the most time, a lot of one-on-one time. Then I try to put together at least a week of the main cast--everyone who’s on for the run of the show, not the day players--where we spend all day sitting around a conference table. In theater parlance it would be called a table read, but we don’t actually read. I basically just act the movie out and say, ‘OK, here’s the first scene. You’re going to come in here.’ Then I talk about what I expect the scene to be. A hand will come up and someone might go, ‘Well, I don’t understand why I’m coming in on that line and not on this one.’ And that starts a whole dialogue. Somebody like Jodie [Foster, in Contact] wanted to read every line in rehearsal and hear what her character would sound like. I’m fine with that, but I generally don’t ask my performers to actually perform during a reading.

Q: You seem to do a lot of one shots.

A: Oh no. They’re very jarring, you’ve got to be using them for effect. A single is a special effect. There’s great power in having both actors in the same frame, even if you’re just feeling a bit of one person’s shoulder. It gives the scene more energy, because you’ve got two actors working with the same timing. Their energy is there, even if one of their faces isn’t. It also keeps the audience very comfortable. Otherwise they’re being a voyeur, and they’re subconsciously being jarred into feeling, ‘Oh yes, this is a close-up.’ Audiences just feel more comfortable when the two characters are both in the same frame. When you have a single, now you’re in the movie with the actor. That works great when it’s time for that effect. But you can’t really do traditional kinds of two singles coverage.

For Flight, with Denzel Washington and Don Cheadle, Zemeckis used 400 effects shots, but focused on the emotional core of the storyAwards in 2012. (below) In Who Framed Roger Rabbit, live action characters were combined with animated ones. (Photos: Paramount Pictures/Touchstone Pictures & Amblin Entertainment Inc.)

Q: Can you get away without shooting singles in terms of coverage?

A: Sometimes you have to do singles if you don’t have a high-caliber cast and crew, because you’ve got to have the safety valve. You can only do elaborate, beautiful cinema when you’ve got really professional people doing the technical things. If you’re working with an actor who absolutely will not match anything because they basically refuse, then your cinema suffers. It’s a selfish and ultimately futile attitude for actors to take, because they have to understand that they’re in a technical art form. At the end of the day, the matching always wins.

Q: Do actors usually understand that?

A: Most actors that I work with are wonderful. Jodie Foster or Tom Hanks will make anything work. I’ll say, ‘I’m sorry, but I need you to do the most unnatural thing and twist your body like this and lean over here and say this line,’ and they’ll say, ‘Yeah, I can do that.’ They’ll make it work, and they won’t chafe about having to do something unnatural. Because everything about making movies is very unnatural. Standing on an apple box is unnatural.

Q: When you do performance-capture animation, you never have to discuss these things with actors. You can basically do whatever you want?

A: Yes, you don’t ever have to discuss mechanics: mo-cap liberates you from having to do any of that. You can separate performance from the craft of cinema, but you still get the magic and emotion of the human performance, and the actor gets to do things that he or she never gets to do in movies. First of all, they get to do the scene in continuity, from beginning to end, with all the other actors. They get to pace the scene just like they were doing it on the stage. They’re running the scene, feeding off each other. And they get to work all day long. They’re not sitting around for 12 hours to work 20 minutes. They get to act for eight hours. Every actor I’ve ever done this with has truly enjoyed it, and then I get to, with complete control, put the camera in wherever I want. The actor doesn’t have to suffer and lean on this left foot, so he doesn’t shadow the other actor, and if he wants to lunge forward, he doesn’t get beaten up because it buzzes the focus or all that other stuff. To me, digital cinema is very liberating.

Q: From its opening shot of a feather falling and falling, Forrest Gump really paved the way for you with digital cinema. When did you first hear the words ‘Forrest Gump’?

A: Jack Rapke, my agent at the time, said, ‘I really need you to read this script. It’s a quality piece.’ He actually said, “It’s a quality piece.” (laughs) He never shot-gunned stuff to me, and when he said something was good, I read it. I remember I didn’t want to stop reading it. All these thoughts and feelings were going through my mind at the same time. I wanted to find out what was going to happen at the end, and yet there was no traditional dramatic convention propelling the story; just the characters. When that happens, it’s always a good sign. I had the same feeling with Flight, by the way.

Q: The digital effects in Forrest Gump were amazingly real, especially Gary Sinise’s amputated legs. How did you do those shots?

A: With Gary’s legs, we were able to do our shot and then we could graft the legs off and “paint” the little stubs using digitized pixels from the way his pants’ fabric looked. Then we could light them digitally as well. We also had a magician come in and build a false-bottomed wheelchair so, for a lot of shots, Gary’s legs were folded under in an illusion chair. But in the bigger shots, like when he’s on the floor of his apartment and he pulls himself back onto the chair, those were done with Gary wearing blue screen socks from the knee down, and I’d shoot the coffee table and all the other elements in the room. As I was shooting all of this in VistaVision, I also had B cameras filming Gary from the waist up—so I could get him in his chair without showing his stumps, in case the digital effects didn’t work. As it turned out, they looked better than I ever thought they would.

Q: You’ve worked with Hanks a number of times since then. Do you also like to use the same directorial team behind the camera?

A: A lot of the ADs get elevated to producers, so I have to keep changing them. But I’ve worked with some great ones, including Josh McLaglen. I started working with Cherylanne Martin, one of our executive producers on Flight, when she was a 2nd AD.

Q: What responsibilities do your ADs have in terms of second unit work and shooting inserts?

A: It depends. When you’re doing a big action movie, you’ve got to have second unit directors out there picking up shots that take all day to set up. The second unit filmed a lot of the running on Forrest Gump, where everyone was waiting for the perfect sunset, that kind of thing. We used a running double for Tom, and we would send guys off to do that. But I’m the only director on my films who ever works with the actors. Any time a member of the principal cast is being filmed, I’m there. A lot of the time I find myself filming something because I know exactly what I need. Everybody was kind of scratching their heads and chuckling, but I shot every insert in that cockpit in Flight. I just knew what I needed that dial to be doing, and where the camera had to be. I knew I had to get it the way I saw it in my head. There are no easy shots. Every shot is part of the movie. Every shot has got absolute life in it. Even though I don’t like waiting around to rig stuff for eight hours just to do one shot, if I could do every shot, that’s the way I’d want to do it.

Q: You won the DGA Award in 1995 for Forrest Gump. What do you recall about that night?

A: Listen, the DGA Award is from your peers, so it’s the award you hold the closest to your heart. The way the Guild does its ceremony is great too, because everybody gets to make their speeches before anybody knows the winner, which is really nice. My favorite memory was standing up there with my crew—my 1st AD Bruce Moriarty, 2nd ADs Cherylanne Martin and Dana Kuznetzkoff and my 2nd 2nd David Venghaus, all those guys. You get to go up with your entire team and I remember looking down the line at everybody, and they were all just beaming.

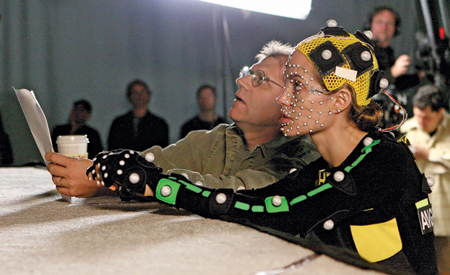

(Top) Zemeckis with Kathleen Turner and Michael Douglas on the set of Romancing the Stone. (Middle) Zemeckis, Tom Hanks, and a skeleton crew camped on small cruise ships near the Fiji coast for Cast Away. (Bottom) Zemeckis approached performance capture on Beowulf (with Angelina Jolie) like any other movie. (Photos: ImageMovers/AMPAS/20thCenturyFox)

(Top) Zemeckis with Kathleen Turner and Michael Douglas on the set of Romancing the Stone. (Middle) Zemeckis, Tom Hanks, and a skeleton crew camped on small cruise ships near the Fiji coast for Cast Away. (Bottom) Zemeckis approached performance capture on Beowulf (with Angelina Jolie) like any other movie. (Photos: ImageMovers/AMPAS/20thCenturyFox)

Q: Some of your friends and colleagues, including Spielberg, have continued to shoot on film. Yet you’ve been a voracious booster of digital filming and projection.

A: I come at it all completely selfishly: What’s better for my movie? As for me, I love having a camera the size of a softball. I love the idea that the camera operator can operate a shot with one hand, just holding it and moving it around. I love the idea that I was able to tuck those cameras into that airplane cockpit without spending hours to set up wild walls because anyone who’s worked filming on an airplane set knows what a pain that is to do that. It just allows me to get my movie made more quickly and efficiently, and gives me more time to work with the actors.

Q: You used hundreds of CGI shots on Cast Away, which most people don’t even think of as being a digitally enhanced movie.

A: Oh, we used a lot on Cast Away. Huge. Way more [than Forrest Gump]. It’s like everything was a digital shot. We had whole fleets of ships that we had to remove. We had other entire islands that were in the shots that we had to remove. That was a huge effects show.

Q: You brought 120 people to a little island near Fiji. Did you really need that large of a crew?

A: I keep asking this question on every movie, but when you go through the list, it turns out you have to have all these people. Here was the wonderful thing: To get to a hotel that could accommodate 120 people, it was an hour-and-a-half boat ride, each way, to a bigger island. We were never going to get the movie done if we did that, so we hired two small cruise ships that each had 15 staterooms, and we put together a 20-man guerrilla team—Tom and his makeup people, me and the 1st AD, the sound man and the camera crew—and we anchored the boats right off of the island. Before sunrise, we all went to the island so, as the sun was coming up, Tom was there ready to go to work, and we would shoot, shoot, shoot for about two hours in the morning and got so much done. Then the big catamaran would come and drop the gangplank, and the hundred other people would come ashore. Everything slowed down, and the noise level went way up. Then, two hours before sunset, all those people got back on the catamaran and left, and the core team would shoot, shoot, and shoot some more.

Q: What did you learn from your decade making performance-capture films that you were able to use on Flight?

A: I didn’t learn anything. I mean, look, the main thing a director has to do is know when he’s ‘got’ it—having the confidence to know when you’ve got it. What I did learn though doing digital cinema is that when all the actors have gone away, and you now have unlimited choices, how do you make a decision? In live action, there are certain walls you can’t tear down. There are certain realities. It’s raining. Or you only have 12 hours of light. You’ve got to figure out the angle if you’re going to have that window in the shot. You have very real world limitations, whereas in digital you don’t have any. So that very much dictates the cinema for you. [In digital cinema], I could do anything I wanted. And you know what? [I decided] I’m just going to do what I always do in live action. Then, having the confidence to find out that that’s what always worked in the digital cinema, I found myself, strangely enough, being so much more confident when I walked onto Flight in just saying, ‘This is the shot. This is how we’re going to shoot this.'

Q: As a director, you’re not usually known for the kind of acrobatic shots composed by Scorsese or De Palma.

A: Well, I have a philosophy about that. I work really hard to try to keep film technique invisible. You want to have the audience get lost in the movie, so they’re not actually paying attention to whether or not the camera is creeping in on someone.

Q: And yet on Flight you had 400 digital effects shots while working on a relatively modest $31 million budget.

A: That is true. A group of guys who started out in my company, ImageMovers, have their own operation now up in Northern California called Atomic Fiction. They’re young and hungry and they’ve got proprietary software doing their own effects. But the main thing is they’re taking advantage of the cloud to rent processing time so they didn’t have to build giant mainframes, which is the biggest expense of owning a digital facility. It’s a matter of horsepower to create any digital image; you just have to have the processing power. It’s definitely going to get cheaper and cheaper, which will be good for movies because, hopefully, it’ll end up just being used for the story, and not as a spectacle for spectacle’s sake.

Q: So where do you think filmmaking is going in the next few years?

A: My prediction has always been that the editing suite will have another technician and another paintbox, and you’ll edit your film and sound and adjust your images digitally. Either an editor or a digital artist will add clouds to the sky, or make a red tie a deeper maroon, or change the shade of green on the leaves. You do all of that in an effects house now, but I think that will be done right there in editing. That’s what I think will happen sooner than anything else. You’ll be able to do rudimentary effects work right then and there, in the editing bay.

Q: After working on three performance-capture films was it hard for you to go back to live action for Flight?

A: No. I’m a purist in the sense that I think moving images with sound and music that are projected in a theater are movies. And movies are movies are movies. That’s how I approach it. I don’t do anything different whether it’s a digital movie, or a documentary, or live action. I do all the same work.